Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2020/The Challenges and Benefits of FSC Certification to Community Forests: A Case Study of The Burns Lake Community Forest, British Columbia, Canada

The Challenges and Benefits of FSC Certification to Community Forests: A Case Study of The Burns Lake Community Forest, British Columbia, Canada

Summary

In British Columbia (BC), the progress of adopting Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification is slower than other provinces[1]. McDermott (2012) suggested that this is because the FSC BC standard is overly prescriptive and costly[1]. Nonetheless, several community forests in BC have successfully attained the FSC certification[2][3]. By examining the Burns Lake Community Forest, this case study aims at understanding what benefits the FSC certification entails, how these associated challenges can be overcome, and what recommendations can be made. The Burns Lake Community Forest adopted the FSC certification to create stronger partnerships with the indigenous communities[4], and an improved public engagement strategy was developed as a result[4]. A non-profit network has played a key role in the attainment of the FSC certification. The Burns Lake Community Forest is recommended to create a certified supply chain, recruit more indigenous workers, and improve its participatory governance.

Keywords

Community Forestry; forest certification; Forest Stewardship Council; Burns Lake; Indigenous

History and Context

Burns Lake Community Forest

The Burns Lake Community Forest centres around the village of Burns Lake, which is located 222km west of Prince George in British Columbia [5]. The community forest covers 92,278.8 ha of crown land, and around 62,000 ha of the forest land is categorized as timber harvest land base[6] .

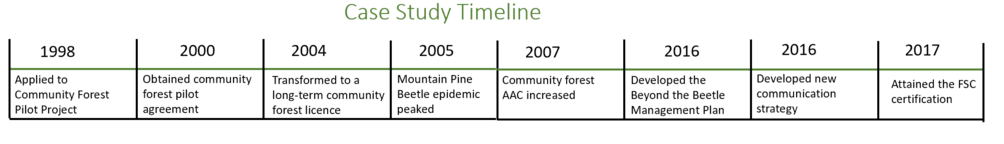

The history of the Burns Lake Community Forest is characterized by a strong collaboration between the First Nations and the local communities. In 1998, the Village of Burns Lake applied to the Ministry of Forestry to participate in the community forest pilot project, and the Office of the Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chiefs was one of the original signatories in the application. Two years later, the Village of Burns Lake was granted the Community Forest Pilot Agreement with an area of 23,325 ha. The pilot agreement started with an overly high stumpage fee until it was decreased one year later through negotiations with the provincial government. The pilot project transformed into a 25-year long-term Community Forest License in 2004. The later expansion of the community forest was closely related to the tenure contribution from First Nations. By 2007, Wet’suwet’en First Nation and the Burns Lake Band have logged more than 28,000 m3 from the area under the Burns Lake Community Forest licence. In 2017, Burns Lake Community Forest received its Forest Stewardship Council certification [3], which fulfilled the community forest agreement’s terms of having a recognized forest certification [5].

Although it is a requirement for the Burns Lake Community Forest to attain a recognized forest certification, several other options exist other than the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certifications. Other recognized forest certification schemes include Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) and the Canadian Standards Association (CSA). Both are less prescriptive and unsurprisingly have a higher rate of adoption by other forestry producers [1]. To understand why the Burns Lake Community Forest chose FSC over the other certifications, the history of FSC in BC should also be considered.

FSC in the Regional Context of BC

British Columbia had its own forest certifications before the arrival of the FSC certification. According to McDermott (2012), forest certification first appeared in BC in the 1990s. One example is the Silva Forest Foundation that assisted local forestry producers to improve their practices and certify them according to the foundation’s own environmental standards [1]. In 1993, FSC was established, and the certification gained global attention because it addressed the tropical forest loss through changing the global forest supply chain. The governance system of FSC had a set of global principles and criteria, and regional indicators were developed to fit them into the local contexts. Decisions such as the making of regional standards required two third of a balanced vote from all three of the economic, environmental, and social chambers of FSC. FSC Canada’s regional governance system added an indigenous chamber to this system with the power to veto. MCDermott (2012) argued that this addition had further limited the voting power of the economic sector.

The FSC BC standards were developed in the context of conflicts. In the late 1990s, several Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) supported the old-growth forest campaign, and they urged large retailers such as Home Depot to source only FSC certified wood from BC. Although the result of the campaign was frustrating, attention had been brought to the drafting of FSC BC standards, which was finalized in 2005. McDermott (2012) criticized this BC standard for being overly prescriptive and procedural. The author explained that it was caused by a lack of trust in the standard making processes. McDermott (2012) pointed out that although the industry did not support this standard, their voting power was not enough to veto it The growth of FSC in BC has been slower than the rest of Canada; only 4.7% of the total forest area in BC is FSC certified versus an average of 13.1% in the other Canadian provinces [1].

Tenure Arrangements

In British Columbia, a community forest agreement is a timber-harvest license on the land that is owned by the provincial government. The development of the community forest agreement program in BC started in 1998, which was the same year that the Burns Lake Community Forest participated in the program. The pilot program granted community forests five-year timber-harvest licenses, and these five-year licenses became 25-year long-term agreements in 2009[7]. For Burns Lake Community Forest, its tenure was transformed into a long-term Community Forest Agreement in 2005 as one of the first long-term agreements. These long-term agreements can be renewed every 10 years; however, the Ministry of Forests has the power of controlling Community Forests’ renewal and area expansion [5]. Comfor Management Services Ltd. (CMSL) holds the CFA.

The Burns Lake Community’s ownership of a community forest agreement entails many but not all rights to the crown land that the agreement covers. The area-based timber harvest license allows the community to extract timber from within the boundary of community forest while excluding others from this extraction; however, many responsibilities come with this extraction right. The agreement also requires Burns Lake Community Forest Ltd. to develop a 5-year operational plan to manage the logging activities. Silviculture planning is also required to control the cultivation and growth of the forest. Although these requirements require financial and human resources from the community, they also allow the community to enforce their own forest management plan. This allows the community to have greater control over values such as non-timber forest products, recreation facilities, and conservation. Furthermore, the community has the freedom of allocating logging and silvicultural contracts within their community to generate more employment [7]. Unlike the other timber harvest licenses, the community cannot sell their license. Along with the general rights and requirements for all the community forests, these community forest agreements can also include specific terms. For Burns Lake Community Forest Agreement, one of these terms was set to require the attainment of a recognized forest certification before March 31st, 2017.

Community forest agreement in BC was categorized as a relatively complete form of co-management by Pinkerton (2018). The author explained this categorization was based on how these rights have given the community a strong base to make collective choices and plan forest operations while the government and public also have many controls over the forest. Additionally, the ministry will review the management plan and set annual allowable cuts every five years while the public can review and comment on the plan [7].

Administrative Arrangements

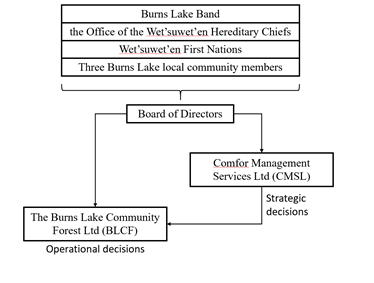

As indicated in figure 1, the administrative arrangement at the Burn Lake Community Forest is centered around three entities. They are The Burns Lake Community Forest Ltd. (BLCF), Comfor Management Services Ltd (CMSL), and a board of directors [5]. Incorporated as part of the community forest application to the Ministry of Forests, The Burns Lake Community Forest Ltd. is governed by a board of directors who is appointed by the mayor and council of the village of Burns Lake. Among this board of directors, three seats are reserved for the three Indigenous groups, and they are Burns Lake Band, Wet’suwet’en First Nations, and the Office of the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs. The other three members are from the Burns Lake local community appointed by the village. The board of directors governs both BLCF and CMSL [5].

Figure 1

Administrative structure

Note: Three entities are involved in the management of the Burns Lake Community Forest

BLCF is responsible for managing the forestry activities in the community forest. Local contractors are hired for harvesting and silvicultural activities to generate local employment and economic benefits. The logs, harvested through forest management, are sold to local facilities on a priority basis, and the revenue from selling is in turn used to share profits with First Nations, fund operations, and donate to the community [5]. On the other hand, CMSL is responsible for providing accounting and administrative support to BLCF, including the development of forest management plans, annual reports, and public relationships. CMSL is also a parent company of BLCF, which owns 100% of the shares of the BLCF and other subsidiaries associated with the community forest, including Endako River Timber Ltd. [5].

While the ultimate management authority lies in the board of directors, strategic decisions such as purchasing other businesses are mostly carried out by CMSL. Finally, the decisions at the operation level are made by BLCF, which also holds both the community forest license and the FSC certification [5].

Social Actors

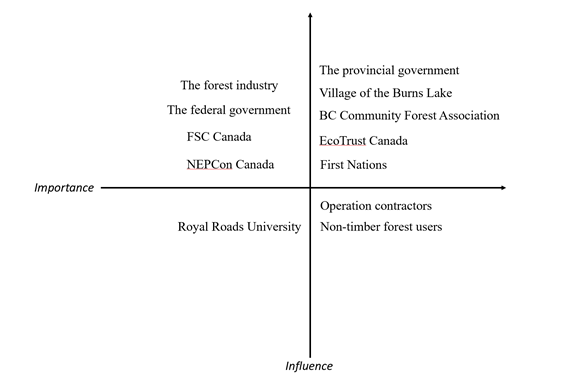

Figure 2

Stakeholder Power Analysis

Note: The social actors are separated into four categories based on their influence and importance.

Both the management of the Burns Lake Community Forest and its attainment of FSC certification have involved multiple social actors. As shown in Figure 2, the social actors that are involved can be separated into four quadrants based on how important the project is to them and their level of influence. One of the important distinctions between these social actors is that some are affected social actors that are subject to the effect of the forestry activities at the Burns Lake Community Forest while others are interested social actors, who are linked to the community forest by economic transactions or activities.

Affected Social Actors

There are four groups of affected social actors involved in the development of the Burns Lake Community Forest. These groups have long-term relationships with the forest because they are either emotionally connected to the land or economically dependent on the forest for their livelihoods. Each of these groups have a different level of power and their own distinct objectives as listed below.

Table 1

Affected Stakeholders

| Affected Stakeholders | Objectives | Relative Power |

| The village of the Burns Lake | Improving tourism and recreation service and local employment, Implementing Wildfire Protection Plan | High, have three seats on the board of directors, easy access to mayor and council |

| Burns Lake Band and Wet’suwet’en First Nations (Rights holder) | Developing the economy of indigenous communities, protecting indigenous culture and values | High, have three seats on the board of directors, are well engaged after attaining the FSC certification |

| Non-timber forest users | Recreation, trapping, range use, oil and gas, mining, Fire Training society | Medium, they are consulted and have a chance to review and comment on management plans. |

| Local silviculture and logging contractors | Employment | Low in decision making power but are prioritized to hire. |

Note: The affected stakeholders, their objectives, and relative power are listed.

Interested Social Actors

Although many interested social actors have made great contributions to the project, they do not depend on the community forest on a long-term scale. The following table summarizes who are these interested social actors, what are their objectives, and what levels of power do they have.

Table 2

Interested Social Actors

| Interested Stakeholders | Objectives | Relative Power |

| Eco-Trust Canada | Facilitates rural and indigenous community development | Medium, assisted in attaining and managing FSC certification |

| Northern Development Initiative Trust | Stimulates economic growth in central and northern British Columbia | Medium, provided financial assistance to the community forest |

| NEPCon Canada | Maintains credibility as an FSC-accredited certifier | High, has the power of filing FSC non-conformity reports |

| FSC Canada | Increases the area of certified forest, realizes its global principles and criteria | High, can revise standards that govern the community forests. |

| BC Community Forest Association | Advocates community forestry in BC | High, can offer support and influence governmental decisions such as stumpage rate. |

| The forest industry | Maintains stable fibre supply and market dominance | High, has a close relationship with the provincial government and market control |

| The provincial government | Increases voter support, social stability, tax revenues | High, has direct control of tenure forms and the crown land |

| Royal Road University | Gains academic reputation through research projects | Low, researched non-timber forest product opportunities for BLCF |

| The Federal Government | Manages fishery resources in the community forest | High, has legislative and executive power over indigenous issues |

Note: The interested social actors, their objectives, and relative power are listed.

Together these social actors form a multi-level governance system. Locally, the Burns Lake Community Forest is governed by the First Nations and the members of the municipality. On a regional scale, the provincial and federal governments govern the tenure form of community forests and indigenous relationships. Internationally, FSC develops the standards that govern the forest management practices of the certified forestry organizations.

Multi-Level Governance

Local Governance

The Local Governance of the Burns Lake Community Forest are carried out mostly by The Village of the Burns Lake and the First Nations, and their decision making processes are also influenced by the non-timber forest users.

The Village of the Burns Lake (2020) mentioned that its objectives include developing tourism and recreation services such as mountain bike trails and parks, implementing its Wildfire Protection Plan, and being financially sustainable for infrastructure development[8]. The municipality has a relatively high level of power because it has half of the seats in the board of the directors, and the municipality also has little communication barriers with other social actors. On the other hand, Wet’suwet’en First Nation and the Burns Lake Band receive 18% of the after-tax profit from the sales of the logs [6]. This profit will help First Nations to develop the indigenous communities, create employment, and protect their cultures and values [9]. The First Nations have a relatively high level of power because they have the three reserved seats in the board of the directors; however, communication barriers such as language and cultural differences may reduce their influence over the community forest. The non-timber forest users at the Burns Lake Community Forest include the trappers, the range tenure holders, and the recreationists. These users have some influence over the management of the forest because they are consulted and have the chance to review the management plans.

The Power of a Non-profit Network

The reason why the Burns Lake Community Forest was able to attain the FSC certification is that it has a supportive non-profit network. Among this network, Ecotrust Canada and Northern Development Initiative Trust have played important roles in the attainment of the FSC certification [10], which later allowed NEPCon Canada to audit the forestry practices of the Burns Lake Community Forest every year.

Ecotrust Canada aims at facilitating rural economic development and fair distribution of benefits from natural resources [11]. In Ecotrust Canada’s 2017 report, the organization mentioned that it endorsed the FSC certification system because it was more deliberate in engaging local communities and indigenous peoples. To decrease the cost of Burns Lake Community Forest’s FSC certification, Ecotrust included the Burns Lake Community Forest as a member of its FSC group certification. Group certification is a way to provide certification access to small enterprises. By centralizing their collective responsibilities, members of a group certification can greatly reduce their administrative and financial cost [12]. A forestry team from Ecotrust Canada has supported the certification process for 18 months [11]. Nowadays, the certificate manager of Ecotrust Canada is still working as a consultant for Burns Lake Community Forest [3].

Northern Development Initiative Trust is funded by the BC provincial government but it operates independently from the government. Through funding community-led projects, Northern Development Initiative Trust aims to stimulate economic growth in central and northern British Columbia. This organization contributed $30,000 to reduce the financial barriers faced by the Burns Lake Community Forest [13].

Furthermore, many other successes of the Burns Lake Community Forest can be associated with the support of its non-profit network. One example is the Office of the Wet'suwet'en, which reduced the communication barriers in the establishment of the community forest. Also, BC Community Forest Association represented the community forests to negotiate for a reduced Stumpage fee, which was crucial to the survival of the Burns Lake Community Forest [5].

Federal and Provincial Governments

Both the provincial and federal government are highly influential to the success of the Burns Lake Community Forest. The provincial government governs the tenure form of the community forests and has control over their Annual Allowable Cuts and Forest Management Plans. On the other hand, the federal government has responsibilities and power over indigenous issues and fishery resources in the community forest. Also, McDermott (2012) pointed out that the forestry industry has a close alliance with the provincial government[1], and Pinkerton (2018) mentioned that the major forestry companies control the log markets in British Columbia and procured 78% of logs produced by community forests[7].

Discussion

In its annual report, CMSL (2019) wrote that one aim of the community forest management is to improve public involvement. The progress of this aim is relatively successful after the community attained the FSC certification[6].

The Impact of FSC Certification

The FSC certification was chosen by the community to serve as a social license instead of a marketing tool. Mulkey et al. (2018) explained that the FSC certification was chosen for its requirement of building a strong relationship with the First Nation communities. Despite how the First Nations were the original signatories of the community forest agreement, the indigenous communities were not well engaged initially[4]. According to the management plan in 2016, the First Nations were consulted through three methods at that time[5], and they were:

- sending invitation letters to First Nations to comment on the Forest Stewardship Plan,

- giving chances for First Nations to comment on the planning of harvesting blocks and road construction, and

- meeting with First Nations when a request was made

These three methods did not given much support in helping the First Nations to understand and participate in the planning processes. Mulkey et al. (2018) wrote that a new communication strategy was developed while attaining the FSC certification. This strategy was developed through multiple meetings with the First Nation Communities to communicate how communication should be[4]. These meetings included questions such as:

- What information is needed through what medium?

- Who needs to know this information and how can they be contacted?

Mulkey et al. (2018) also suggested to follow the schedule of the indigenous communities, present information in proper ways, and review the strategy annually. Developed for the FSC certification, this new communication strategy has created a strong contrast with the previous passive way of engagement[4]. Thus, the aim of creating a strong relationship with the First Nation communities has proved to be successful.

The Mountain Pine Beetle Attack

One major obstacle for the Burns Lake Community Forest was the mountain pine beetle attack on its forest, which resulted in a financial crisis and employee turnovers. In 1999, the mountain pine beetle epidemic arrived at the Burns Lake Community forest and peaked in 2005 [5]. The community forest was forced to focus on salvaging logs and reducing its economic loss. As a result, the support from the public had significantly decreased [4]. As a response to this crisis, the community forest developed the Beyond the Beetle Management Plan and more transparent public engagement processes in 2016[5]. The “Beyond the Beetle” management plan adopted an adjusted economic model, a significant environmental program, and an improved silviculture program [5].

Recommendations

For the community forests that are trying to attain FSC certifications, lessons can be drawn from the successful outcomes of the partnerships between the non-profit organizations and the Burns Lake Community Forest. This non-profit network has helped the community forest in initiating its community forest pilot project, decreasing the stumpage fee, and attaining the FSC certification. The importance of non-profit networks is well supported in other literatures. In reviewing the case study of the Zanzibar community forests [14], CARE international helped the local communities in overcoming a racialized landscape, which is similar to the role of Office of the Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chiefs. In the same case study, development-oriented NGOs that are similar to Ecotrust Canada also successfully improved the local capacities of a community forest[14]. Built upon the successful experiences in both Burns Lake Community Forest and the Zanzibar community forest case study, it is recommended that community forest managers should aim at expanding their non-profit networks.

The Burns Lake Community Forest will create more economic benefits for the local communities if the local log processing facilities have also attained their FSC certifications. Chen et al. (2010) wrote in their article that two of the main benefits from attaining a voluntary forest certification are a larger market access and a price premium. Despite the authors description of an immature market for certified wood products [15], many large companies are starting to prefer using the FSC certified paper. For example, MacDonald’s has committed to only using FSC certified paper in their guest packaging by 2025 [16]. However, the Burns Lake Community Forest cannot capture these advantages unless its down-stream log processing facilities are also FSC certified. While the community can choose to sell to certified processing facilities that are not local, it is against its goal of supporting the local economy. Therefore, by helping local processing facilities to become FSC certified, the Burns Lake Community Forest will be able to fully utilize the benefits of its FSC certification while capturing economic benefits locally.

In the case study of the Meadow Lake community forestry, Andrew-Key et al. (2020) pointed out several principles that led to the success of the community forestry[17]. Since the Meadow Lake community forestry shares many similarities with the Burns Lake Community Forest, these principles behind the success of the Meadow Lake community are applicable to the management of the Burns Lake Community Forest[17]. Both of these communities adopted FSC certification to improve their environmental stewardship and public engagement processes, and both involved a strong collaboration between the indigenous and non-indigenous communities. Andrew-Key et al. (2020) wrote that Meadow Lake Community has established co-management boards and the Public Advisory Group to facilitate participatory governance[17]. While the Burns Lake Community Forest has a co-managed board of directors, it should also consider establishing a forum that includes all stakeholders that are affected by the forest management activities. This forum will facilitate better communication with the non-timber forest users and local contractors. Andrew-Key et al. (2020) also pointed out the importance of recruiting and training both indigenous and non-indigenous workers throughout the administrative structure of community forestry. The authors explained that this helps the community to be competitive in the industry and helped them to go through an economic crisis [17]. While the Burns Lake Community Forest has prioritized hiring contractors from the First Nations, it should also consider recruiting and training indigenous workers to work in the CMSL and BLCF which will further improve the competitiveness and stability of the Burns Lake Community Forest.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 McDermott, C. L. (2012). Trust, legitimacy and power in forest certification: A case study of the FSC in British Columbia. Geoforum, 43(3), 634–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.11.002

- ↑ Forest Product Association of Canada. (2019). Forest Management Certification in Canada: 2018 year-end status report British Columbia [PDF]. Retrieved from https://certificationcanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2018-Yearend-SFM-Certification-Detailed-Report-BC.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 NEPCon Canada (2020). FSC Forest Management certification: 4th surveillance audit [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://blcomfor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Ecotrust-FSC-FM-audit-19-Client_FINAL.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Mulkey S., Varga F., Manhas S. (2018), FSC certification: standards for community engagement [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://bccfa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/CFA-Social-License-and-Collaboration-signoff-May-15.pdf

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Lester, G. E. & Varga, F. (2016). Management Plan #3: Burns Lake Community Forest [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://blcomfor.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Burns-Lake-Community-Forest-Management-Plan3_2016_05_09.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 ComFor Management Services Ltd. (2019). Annual report: November 1st, 2018 to October 31st, 2019 [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://blcomfor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/2018-2019-Annual-Report.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Pinkerton, E. (2018). Benefits of collaboration between indigenous and non-indigenous communities through community forests in british columbia1. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 49(4), 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2018-0154

- ↑ Village of Burns Lake. (2020). 2020 Municipal Objectives [PDF]. Retrieved from http://office.burnslake.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020-Municipal-Objectives.pdf

- ↑ Wet'suwet'en First Nation. (2015). Economic development objectives [webpage]. Retrieved from https://wetsuwetenfirstnation.com/business-and-development.html

- ↑ Varga, F. (2017), Burn Lake Community Forest Achieves Globally Recognized Certification [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.northerndevelopment.bc.ca/news/burns-lake-community-forest-achieves-globally-recognized-certification/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ecotrust Canada. (2018). 2018-2021 Strategic Plan [PDF]. Retrieved from https://ecotrust.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Ecotrust-Canada-2018-2021-Strategic-Plan.Update.pdf

- ↑ FSC Canada. (2020). Group certification [webpage]. Retrieved from https://ca.fsc.org/en-ca/certification/chain-of-custody-certification/group-certification

- ↑ Northern Development. (2020). About us [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.northerndevelopment.bc.ca/about/

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Menzies, N. (2007). Jozani Forest, Ngezi Forest, and Misali Island, Zanzibar. In Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber: Communities, Conservation, and the State in Community-Based Forest Management (pp. 30-49). New York: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/menz13692.6

- ↑ Chen, J., Innes, J. L., & Tikina, A. (2010). Private cost-benefits of voluntary forest product certification. International Forestry Review, 12(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.12.1.1

- ↑ Global Newswire (2018), By 2025, all of McDonald’s packaging to come from renewable, recycled, or certified sources [webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2018/01/16/1289558/0/en/By-2025-all-of-McDonald-s-Packaging-to-Come-from-Renewable-Recycled-or-Certified-Sources-Goal-to-Have-Recycling-Available-in-All-Restaurants.html

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Andrews-Key, S., Wyatt, S., & Nelson, H. (2020). Mistik, Norsask, Meadow Lake Mechanical Pulp, and the Meadow Lake Tribal Council: A Community Forestry approach to large-scale industrial forest management and production. In J. Bulkan, J. Palmer, A. M. Larson, & M. Hobley (Eds.), Handbook of Community Forestry Community Forestry. Routledge.