Course:SPPH381B/Essay 2/Occupational Respiratory Disease - Samin

Occupational and environmental exposures increase the risk of asthma, COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) and many other respiratory diseases like black lung disease (coal worker’s pneumoconiosis), silicosis, rhinitis, laryngitis, tracheitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis and lung cancer. These respiratory diseases are predicted to become the third leading cause of death by 2020, according to the World Health Organization.[1] The respiratory tract is often the site of injury from occupational exposures because it has direct contact with the ambient environment. The burden of occupational respiratory diseases (ORDs) is increasing rapidly worldwide, especially in developing countries.[2] Identifying workplace-related causes of a disease is important because this can lead to finding a cure and to the prevention of other occupational respiratory diseases.

Major types of respiratory diseases

Prolonged exposure to particles of dust (like silica, asbestos, wood, pollen, water mist, etc.) can result in lung diseases. All the gas molecules are millions of times smaller than solid particles; they just get mixed up with air molecules and they make it all the way to the alveoli, and many will get absorbed by the blood like oxygen does. There are exceptions – if a gas is very reactive – like Chlorine – then it can react with water in the lining of the airways and can cause irritation high up in the respiratory tract. Other examples include exposure to asbestos leading to asbestosis and mesothelioma. People who work with beryllium, such as aerospace workers, are at risk of beryllium disease. People who work with cotton, flax, or hemp are at risk of byssinosis and workers exposed to silica are at risk of silicosis. Exposures to gas and chemicals may occur at work as well (farmers, for example, are exposed to various types of pesticides that can be toxic when inhaled) or in the home.

Byssinosis

Byssinosis also known as “brown lung disease” or Monday fever is an occupational lung disease that is caused by cotton dust exposure in inadequately ventilated working environments “ [3]. Cotton dust is known to directly cause byssinosis, which includes symptoms of breathing difficulties, chest tightness, wheezing and coughing [3].

Rhinitis

Nasal hair filter particles and moist tissues of nose absorb gasses. Rhinitis is irritation and inflammation of mucous membrane inside the nose due to inhalation of allergens which further cause sneezing, itching or congestion.

Laryngitis

Laryngitis is a disease which is caused due to inhalation of allergens, irritants such as chemical fumes or smoke by causing vocal cords to be strained and other injuries on the vocal cords.

Tracheitis, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis

Tracheitis, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis occur due to inflammation of trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles, respectively. This often happens during the production of occupational substances that result in industrial bronchitis, just as cigarette smoke causes smoker's bronchitis. Bronchitis may be found in people whose occupation involves exposure to dust or who work in chemical and food processing, mining, storage and processing of grains and feeds, cotton-textile milling, and welding.

Parenchymal lung diseases

Parenchymal lung diseases are caused by metal inhalation that includes interstitial fibrosis, giant-cell interstitial pneumonitis, chemical pneumonitis, and granulomatous disease. In a study[4], two cases of granulomatous lung disease with occupational exposure to metal dusts other than beryllium were reported. These two workers had worked in the battery manufacturing industry for 7 years and in an aluminum processing factory for 6 years, respectively. The results revealed granulomatous lesions in the pulmonary interstitium. Analysis by an electron probe microanalyzer with a wavelength-dispersive spectrometer (EPMA-WDS) confirmed the presence of silicon, iron, aluminum, and titanium in the granulomas. Aluminum was found in a high concentration in the granulomatous lesions. This suggests that metal dust other than beryllium can induce granulomatous lung diseases.

Occupational asthma

More than 250 substances found in the workplace cause occupational asthma [5]. It is characterized by episodic narrowing of the respiratory tract. People who work in isocyanate manufacturing, who use latex gloves or who work in an indoor office environment are at a higher risk for occupational asthma. Asthma is a classic obstructive lung disease. People with obstructive lung disease have shortness of breath due to difficulty exhaling all the air from the lungs. Because of the damage caused to the lungs or narrowing of the airways inside the lungs, exhaled air comes out more slowly than normal. At the end of a full exhalation, leaving an abnormally high amount of air lingering in the lungs. Certain chemicals cause this restriction in the airways. We call them as respiratory sensitizers (because lungs are sensitive and they react to it).

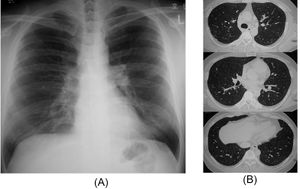

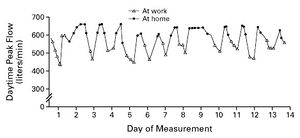

The results from a study of a 42-year old man showed that the airflow obstruction was temporally related to exposure in the workplace and can be identified by having the patient to record peak expiratory flows, both at work and away from work. It was observed that the asthma was related to work.

In another case-control study, the risk of developing obstructive lung disease in relation to occupational exposures in hairdressers. It was reported that the respiratory and allergic symptoms were particularly aggravated after work exposure to bleaching powder and hair spray [1].

Carcinoma

In the case of lung cancer, at least 12 substances found in the workplace are classified as human lung carcinogens[5]. Cigarette smoke and asbestos interact strongly in causing bronchogenic carcinomas, and the risk of carcinoma is greater in people with the interstitial fibrosis of asbestosis. Many asbestos-related lung cancers occur in pipe insulators, building-construction workers, shipyard workers [5]. Lung cancers are very common and one of the mechanisms which it occurs is through the mechanism of particle disposition (chemical method). Most of the tobacco ends up at the carinal ridge where particles accumulate and get stuck to it.

Coal worker's pneumoconiosis

Another important respiratory disease to consider is the coal worker's pneumoconiosis (black lung). Coal mine dust causes a spectrum of lung diseases known as coal mine dust lung disease (CMDLD). These include coal workers pneumoconiosis, silicosis, dust-related diffuse fibrosis (which can be mistaken for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CMDLD continues to be a problem in the United States, particularly in the central Appalachian region. Treatment of CMDLD is symptomatic[6]. Those with an end-stage disease are candidates for lung transplantation. Because CMDLD cannot be cured, prevention is critical.

Developing countries

In the case of developing countries like India, it is estimated that 1 million people are employed in the mineral sector in India, with more than one-third in coal mining[2]. There are over 3 million workers that are continuously exposed to silica dust, and 8.5 million more work in construction and building activities, similarly exposed to quartz[2]. By providing objective measures of disease incidence, prevalence, or mortality, as well as allowing for the identification of sentinel events, surveillance stands as the basis for the development of public health policies and interventions to reduce the burden of ORDs worldwide.

Prevention

One of the main strategies is to protect workers from being exposed to dangerous levels of hazardous substances. This can be achieved by implementing the strategy, changes in work practices and technological controls. Substitution is the best way to prevent hazardous emissions (i.e. replacing hazardous substances with those that are less hazardous). Imposition of ventilation system and process exposure which do not allow release of gases and toxic particles into the air to prevent airborne exposure. Use of protective gear and respirators has been the least satisfactory method of preventing occupational respiratory exposures. However, respiratory disease such as Byssinosis can be reduced to some extent for workers by providing working environments with sufficient ventilating or respirators [3]. All approaches used for reducing exposure to hazardous substances in the workplace should be supported by stringent enforcement of law and through periodic review of current legal standards that regulate occupational exposure. Another important strategy is to provide education on hazards and ways to reduce risk of exposures by educating workers in identifying hazards, in safe work procedures and use of respirators in an emergency

Conclusion

In order to tell if the worker is experiencing occupational respiratory disease symptoms, we can use pulmonary function testing. This graph can tell us that something at work is causing the airways of the workers to reduce their power of breathing. New opportunities to prevent occupational lung diseases require the discovery of new occupational lung diseases, new settings for recognized occupational lung diseases, and new approaches to their prevention. Population‐based multidisciplinary follow‐up of sentinel cases can enable occupational health professionals, especially in developing countries to recommend risk‐based preventive measures for emerging lung diseases as ORD surveillance data remains scarce in most countries[2] .

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hashemi, N., Boskabady, M. H., & Nazari, A. (2010). RESPIRATORY CARE. Occupational Exposures and Obstructive Lung Disease: A Case-Control Study in Hairdressers, 55(7), 895-900. Retrieved March 16, 2017, from http://www.rcjournal.com/contents/07.10/07.10.0895.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Pinheiro, G., & Antao, V. (2015). Surveillance for Occupational Respiratory Diseases in Developing Countries. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 36(03), 449-454. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1549456

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/81-123/pdfs/0152.pdf

- ↑ Tomioka, H., Kaneda, T., Katsuyama, E., Kitaichi, M., Moriyama, H., & Suzuki, E. (2016). Elemental analysis of occupational granulomatous lung disease by electron probe microanalyzer with wavelength dispersive spectrometer: Two case reports. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports, 18, 66-72. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.04.009

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Beckett, W. S. (2000). Occupational Respiratory Diseases. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(6), 406-413. doi:10.1056/nejm200002103420607

- ↑ Laney, A. S., & Weissman, D. N. (2014). Respiratory Diseases Caused by Coal Mine Dust. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56. doi:10.1097/jom.0000000000000260