Course:RSOT513/2011/CVA

Ischemic Stroke in the Frontal Lobe

Etiology

A stroke, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA), is the sudden disruption of blood flow to the brain and surrounding tissues resulting in neurological deficits. (1) Strokes are generally categorized as hemorrhagic or non-hemorrhagic. (1) Non-hemorrhagic strokes, more commonly called ischemic strokes, account for 87% of all strokes. (2)

Ischemic Stroke

Ischemic strokes occur when a specific area of the brain does not have blood supply, robbing that area of needed oxygen and nutrients. This lack of oxygen supply results in brain cell damage or death. (1) This interruption of blood supply is caused by either an embolism, which is a blood clot that formed in the body and travelled in blood vessels to the brain, or thrombosis, which is an obstruction due to a blood clot that formed in the brain. (1)

Prevalence and Incidence of Stroke

Currently, prevalence of stroke in Canada (the number of people living with a stroke in Canada), as well as incidence (the number of people diagnosed with stroke each year), are largely unknown as there is no central database to collect this information. (3) It has been estimated that over 300,000 Canadians are living with the effects of stroke. (4)

In the US, it is estimated that the prevalence of stroke is 6,400,000 Americans over the age of 20 years with approximately 795,000 people experiencing a new or recurrent stroke each year. (5)

Common Signs and Symptoms

Warning Signs of a Stroke

While signs and symptoms of a stroke are different depending on the size and location of damage in the brain, the American Heart Association and National Stroke Association (6) report the common signs of a stroke include:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of the face, arm or leg; especially on one side of the body

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden severe headache with no known cause

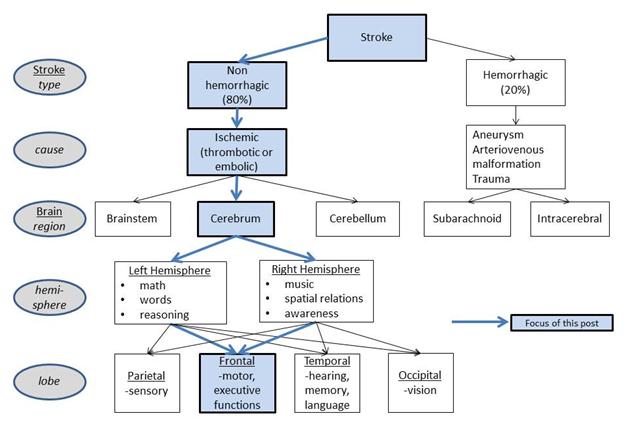

Figure 1: Flow chart of Ischemic Stroke in the Frontal Lobe

Transient Ischemic Attacks

Some individuals may experience “mini-strokes” which are called transient ischemic attacks (TIA). TIAs produce one or more symptoms similar to the above, but the symptoms last for less than 24 hours. Symptoms include (7):

- Fleeting blindness in one eye

- Hemiparesis (weakness on one side of the body)

- Hemiplegia (paralysis on one side of the body)

- Aphasia (impairment of language ability)

- Dizziness

- Double vision

- Staggering

These symptoms are caused by a temporary blockage (between 30 seconds and 10 minutes) of blood supply to the brain. (2) Transient ischemic attacks usually do not cause permanent neurological damage, but are an important warning sign that a more serious stroke may occur. People who have had a TIA are 9.5 times more likely to have a stroke (7)

Risk Factors

There are two main categories of risk factors:

- Preventable: smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, obesity , high blood pressure , and diabetes

- Non-preventable: older age, gender (females are more likely to have a stroke), ethnicity, and family history of stroke (8)

Importantly, most strokes can be prevented by reducing risk factors. (3)

Differential Diagnosis

To distinguish a stroke from other conditions with similar symptom profiles (such as a brain tumour , epileptic seizure , metabolic encephalopathy or a cerebral abscess ) a variety of diagnostic techniques are used. (9) Physical examinations, cardiac testing (electrocardiography, echocardiography to check for irregular heartbeats), neuroimaging techniques, blood tests, and tests of the fluid in the spine may be done by medical staff. (8) Through the use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the location, cause, and severity of a stroke can be determined. As CTs and MRIs may not be able to find small changes in the brain, other diagnostic tools, for example non-invasive studies of blood vessels and invasive studies of the arterial system, may be used. Following diagnosis of a stroke, the individual is evaluated to determine the effects of the stroke. (8) This evaluation is performed by different members of the health care team including doctors, occupational therapists , speech-language pathologists , and physical therapists.

Possible Effects of a Stroke in the Frontal Lobe

Body Function by Brain Location

As different areas of the brain are responsible for specific functions of the body, different patterns of functional loss may result. (10) While a stroke can affect any part of the brain, this Wikipedia post focuses on the effect of an ischemic stroke in the frontal lobe the brain. Because each hemisphere of the brain controls the opposite side of the body, a stroke in the left hemisphere would cause difficulties on the right side of the body, while a stroke on the right side of the brain would cause difficulties on the left side of the body. Some of the major effects of a stroke in the frontal lobe are:

| Brain Area | Difficulty |

|---|---|

| Damage to any area of the frontal lobe | Executive function deficits |

| Damage to posterior (back) of the frontal lobe | Moving limbs (paralysis) |

| Damage to the central (middle) area of the frontal lobe | Moving the eyes Planning movement (apraxia) Speaking (Broca’s aphasia/expressive aphasia) |

| Damage the anterior (front) of the frontal lobe | Attention Understanding/expressing emotion (apathy) |

Recovery Rates

A variety of factors including age, how severe the stroke was, when treatment began, and how effective the treatment was, will affect the recovery rate following a stroke. The National Stroke Association estimates recovery guidelines as follows (7):

- 10% of stroke survivors recover almost completely

- 25% recover with minor impairment

- 40% experience moderate to severe impairments

- 10% require care in a nursing home or other long-term care facility

- 15% die shortly after having a stroke

Occupational therapy (OT) has been shown to play an important part in the recovery process for people who have had a stroke. (11)

Occupational Therapy and Stroke Rehabilitation

Occupations and Occupational Therapy

"Occupational therapy is the art and science of enabling engagement in everyday living, through occupation." (12 p372) "Occupation is everything people do to occupy their time; caring for themselves (self-care), enjoying life (leisure) and contributing to the social and economic fabric of their communities (productivity)." (13 p30) Occupational therapists work with individuals who are experiencing challenges or difficulties while striving to perform everyday occupations that are purposeful and/or meaningful to them. (11,13,14) The occupational therapy process in stroke therapy includes (14,15):

- Assessing the individual’s abilities, skills, and resources

- Identifying the individual’s areas of difficulty and setting goals together

- Helping the individual with deciding on routines and strategies to address difficulties and achieve goals

Assessments

Occupational therapists use assessments to find the areas where their clients are having difficulty performing any activities they need or want to do as a result of injury or illness. (15) Assessment can occur at any stage (observation of occupational performance , intervention to resolve difficulties, or evaluation of treatment outcomes) of the occupational therapy treatment process. (16) The assessments performed by occupational therapists are different from those used by other health care professionals because the goal in OT is to improve function. (14,15) Occupational therapists often use a combination of self-report measures (e.g. questionnaires) and functional assessments (e.g. observation of task performance) to evaluate their client’s potential areas of difficulty. Self-report measures enable the therapist to understand what the individual thinks or feels about their own level of functioning. (15) Functional assessments allow the therapist to observe what the actually does when carrying out certain tasks or activities. (15,17)

Functional Assessments

Functional assessments focus on the three major domains within occupational therapy (self-care, leisure, productivity). Self-care includes activities of daily living (ADLs) such as eating, bathing, and dressing, as well as instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) which include more complex tasks such as grocery shopping, managing finances, and paying bills. (13,17) Leisure includes occupations such as socializing, and participating in sports and outdoor activities. (13) Productivity includes occupations such as homemaking, parenting, and employment. (13) Functional assessments (15):

- Can be informal and formal

- Are done in real life and simulated environments

- Examine both strengths and weaknesses of the person

- Involve observation and analysis of an individual’s ability to complete various every day activities such as:

- Getting dressed (Activities of Daily Living assessment)

- Making a meal (Rabideau Kitchen Evaluation - Revised)

- Using the telephone (Test of Everyday Attention)

- Determine specific impairments and their impact on daily occupational performance

- Guide treatment intervention

- Provide a way to check treatment outcome (e.g. did the therapy work?)

Assessments Used With a Person With an Ischemic Frontal Lobe Stroke

Multiple Errands Test (MET) (18-21)

- Carried out in naturalistic/real world settings (e.g. local shopping area)

- Individual performs multistep tasks requiring executive functioning (e.g. collect specific information, remember to be at particular place at particular time, shop for specific items, follow specific rules throughout assessment)

- Site-specific and simplified versions of assessment been developed and tested (e.g. hospital setting, different cities and shopping centres) as well as virtual environments using video

Behavioral Assessment of Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS) (22)

- Battery of six tests and two questionnaires

- Tests require individual to plan, initiate, monitor and adjust behaviour in response to task demands

- Questionnaires seek information on frequency of particular behaviours

- One questionnaire answered by individual, other answered by family member or caregiver

Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment

Consists of two parts:

- Impairment Inventory assesses physical deficits in 6 dimensions (e.g. postural control, shoulder pain)

- Activity Inventory assesses functional ability in gross motor and walking skills (e.g. transferring to a chair, climbing stairs); amount of assistance required is measured

The Stroke Impact Scale (23)

- Comprehensive self-report measure that considers 8 domains (strength, hand function, ADL/IADL, mobility, communication, emotion, memory & thinking, and participation/social role function)

- Provides measure of an individual’s perceived quality of life, which is of key importance to occupational therapy

While an exhaustive list is beyond the scope of this Wikipedia post, there are numerous non-stroke specific assessments that a therapist may use in the treatment of individuals who have had a stroke in the frontal lobe. These include:

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

- Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE)

- Barthel Index

- Rivermead Perceptual Assessment Battery (RPAB)

- Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS)

- Cognistat

- Chessington Occupational Therapy Neurological Assessment Battery (COTNAB)

- Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT)

- Functional Independence Measure (FIM)

- Trail Making Test Parts A and B[K32]

- Cognitive Assessment of Minnesota (CAM)

- Allen Cognitive Levels (ACL)

- Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB)

- Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA)

- Test of Everyday Attention (TEA)

- Clock Drawing Test (CDT)

- Adelaide Driver Self-Assessment Scale (ADSES)

Occupational therapists decide on which assessment to use based on a number of factors including: cost, time, which assessments/tools are available and best for the client, how accessible supplies/resources needed to carry out the assessment are, qualification requirements to administer the test, the common assessments used at the facility in which the therapist works, and the preference and/or comfort level of the therapist.

Identifying Areas of Difficulty and Implications on Occupation for People Living With The Effects of Stroke

Occupational Performance Issues

Occupational performance issues (OPIs) are related to an individual’s difficulty in their self-care, productivity and/or leisure occupations. Occupational therapists help their clients to identify OPIs (24), and set goals to achieve optimal functioning following a stroke. Following is a sample of potential OPIs that may result from a stroke in the frontal lobe:

Damage to Any Part of The Frontal Lobe

- Executive function

Executive functions are the more complicated thinking skills, for example: planning, problem solving and beginning an activity. The entire frontal lobe plays an important role in using these skills. (25) Therefore, damage to any part of the frontal lobe can result in difficulties with executive functioning. Major difficulties in executive functions can be seen in even the simplest tasks, including the ability to complete one’s own morning routine. (26)

OPI: Self Care

Individuals may have difficulty showering or washing related to inability to begin actions (e.g. which part of the body to wash) and need for instruction from others.

OPI: Productivity

Individuals may have difficulty grocery shopping related to inability to problem solve. If an individual was unable to locate an item in the grocery store, she/he may not be able to think of a solution (e.g. asking a clerk or finding a similar product).

OPI: Leisure

Individuals may have difficulty preparing to go to the recreation center for a swim related to planning and organizing leisure occupations. For instance, one must plan transportation, consider time constraints or pool scheduling, and plan and organize the necessary items (e.g. a clean dry swimsuit, towel, and change for a locker).

Damage to The Back Part of The Frontal Lobe

- Motor damage

Motor damage following a frontal lobe stroke can include muscle weakness or paralysis of one side of the body (opposite to the side of the brain affected by the stroke). (25) Difficulty with movement can lead to decreased participation in everyday occupations. (25)

OPI: Leisure

Individuals may have difficulty performing the physical components of sex with a partner related to muscle paralysis, weakness and/or inability to use both sides of the body.

Damage to The Middle Part of The Frontal Lobe

- Loss of Ability to Move the Eyes

Inability to move the eyes may result in difficulty following moving objects with the eyes (object tracking), inability to accurately and quickly move eyes to look at a new object, and difficulty maintaining focus on an object for a long time. (25)

OPI: Leisure

Individuals may have difficulty with activities like reading related to the inability to maintain visual focus on objects for a long time or difficulties with shifting vision to a new point of focus. (25)

- Apraxia

Apraxia is a movement disorder where individuals can no longer plan, order or perform skilled movements. (14,25) Individuals with apraxia may be unable to carry out activities because they have difficulty following the steps or using objects correctly. (14,25)

OPI: Self-care

Individuals may have difficulty putting on a shirt related to the inability to plan, order, and then perform multiple steps of the movement (e.g. may not position the shirt correctly before putting it on or may do up the buttons first).

- Broca’s Aphasia/Expressive Aphasia

Broca’s area is a region of the frontal lobe that controls the production of speech. Damage to this area of the brain will result in difficulty or inability speaking. (25) Individuals with Broca’s aphasia may avoid situations where they will have to speak to others. (25)

OPI: Productivity

Individuals may have difficulty returning to work related to their inability to verbally communicate with others. (27) In fact, difficulties with speech can lead to unemployment. (25)

Damage to The Front Part of The Frontal Lobe

- Difficulty with Attention

There are many different types of attention: selective, sustained, alternating, divided, and focused. (14) Individuals with a frontal stroke might have difficulties with any one of these attention types. It may seem like they are having trouble focusing on a specific task (sustained), like they are unable to block out distractions (selective), that they are having difficulty shifting their focus between two tasks at once (alternating) or that they are having difficulty managing multiple tasks at once (divided). (14)

OPI: Self-care

Individuals may have difficulty applying makeup in a busy hospital environment related to poor selective attention.

- Apathy

Apathy is the emotional indifference towards all aspects of life. It may lead to decreased motivation and energy levels. (25)

OPI: Productivity

Individuals may have difficulty with completing tasks and performing at work related to lack of motivation and energy.

Occupational Therapy Interventions in Stroke Rehabilitation

Role of Occupational Therapists

The purpose of occupational therapy in stroke rehabilitation is to enable participation in activities of daily living, and improve the quality of life for individuals who have had a stroke. (14) In addition to addressing their client’s occupational difficulties, occupational therapists can provide many other valued services. An occupational therapist can evaluate and assist with their client’s adjustment to the stroke and how they are coping with the resulting rehabilitation process. (17) If their client gives consent, the occupational therapist will want to include the family in their client’s rehabilitation by educating them about the process and how they can be involved. (17) In addition occupational therapists:

- Work with other health care professionals (including doctors, nurses, social workers , speech-language pathologists, psychologists , dieticians and rehabilitation assistants ) to ensure the best care for the individual (17)

- Treat the individual recovering from a stroke in different settings throughout the rehabilitation process including: (17)

- In the acute care hospital setting[DR37] , within a few weeks of the stroke

- In rehabilitation centers where individuals may stay for up to several months following their stroke

- In out-patient clinics after the individual has returned home

- In the individual’s home as a community therapist

- Assist with discharge from the hospital. This involves:

- Determining the right place for the individual to get better in. This may be a rehabilitation center, or it may be home. The OT works with the individual and their family to determine what is the best fit

- Finding out what assistive technologies the individual has at home, and provides information to the individual/family about how to acquire and set-up the equipment. See below for examples of assistive technologies used in the bathroom

- Educate the individual on pressure sores , which 21% of individuals who have had a stroke get, and which are completely avoidable with education and preventive measures

- Fit the individual for a mobility aid such as a wheelchair, scooter, walker or cane that meets the individuals needs and teach the individual how to use it

- Educate the individual on proper body positions in bed and sitting to protect the weak side of the body and avoid pressure sores

- Teach the individual exercises to avoid contractures

- Select and/or custom make splints to prevent and/or correct contractures if they have already formed

- Educate the individual on fall prevention techniques

- Provide information on community resources that may be of help to the individual and their family

- Teach the individual new ways of doing things one-handed if necessary

- Help the individual re-train their body to try to regain lost abilities

Sample Interventions

Occupational performance issues can be resolved by helping people to regain their abilities, or by changing the demands of the activity or physical environment. (28) Below are samples of the interventions an occupational therapist would use with someone who has had an ischemic frontal lobe stroke, based on some of the OPIs outlined above.

Intervention for a Leisure OPI

OPI: The individual is having difficulty participating in sexual activity with a partner related to expressive aphasia, weakness (14), paralysis, apathy, apraxia, executive functioning, and impaired concentration.

OT interventions (1):

- Recommend simple sexual positions

- Help individual establish sexual activity

- Educate individual on non-verbal communication such as touching and gesturing

- Help individual with changing environment to minimize distractions

- Help individual and partner recognize that the individual’s lack of sexual motivation is stroke related, and encourage partner to initiate sexual activity

- Educate individual on ways to conserve energy such as sexual positions that use less energy or engaging in sex during the time of day when energy level is highest

- Provide information on assistive technology (e.g. positioning wedges to make sex easier)

Intervention for a Self-care OPI

OPI: The individual is having difficulty showering related to weakness, paralysis, apathy, poor vision (29), apraxia, impaired executive functioning and impaired concentration.

OT interventions (1,14,29,30):

- Assess individual’s bathroom and suggest assistive technology based on needs to help with weakness and paralysis. Common showering aids include:

- Bath transfer bench/bath board/shower chair

- Non-slip mat

- Tub/stall grab bar

- Long handled sponge

- Wash mitt

- Soap on a rope or suction soap holder

- Pump spray shampoo bottle

- Hand-held shower head

- Towels with loops to anchor for one-handed drying

- Teach one-handed showering skills

- Encourage individual to use the hand and arm affected by the stroke as much as possible

- Create shower routine that includes tips for energy conservation and safety

Intervention for a Productivity OPI

OPI: The individual is having difficulty grocery shopping related to impaired executive functioning, weakness, paralysis, poor vision, expressive aphasia, impaired concentration, apraxia and apathy.

OT interventions (1):

- Give individual a list of community resources for grocery delivery, meal programs, and transportation. Online resources for people with expressive aphasia are particularly useful

- Educate individual on ways to conserve energy (e.g. organizing grocery list according to location in store, using a lightweight cart, placing money in an easily accessible area)

- Teach problem solving skills to help individual solve grocery shopping issues (e.g. difficulty finding items)

- Help individual plan shopping routine and route around store

External Links

- http://www.caot.ca/copm/index.htm

- http://psychology.wikia.com/wiki/Rivermead_Perceptual_Assessment_Battery

- http://www.stroke.org/site/PageServer?pagename=REHABT

- http://www.stroke.org

- http://www.heartandstroke.com

- http://www.chedokeassessment.ca/

- http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/stroke/stroke_what.html

- http://www.strokecenter.org/

References

- Gillen G. Stroke rehabilitation: A function-based approach. 3rd ed. St.Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2011.

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. [Online]. 2011 Feb [cited 2011 Mar 23]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/stroke/stroke_what.html

- World Health Organization. Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke: Risk Factors. [Online]. 2010 [cited 2011 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/cvd_atlas_03_risk_factors.pdf

- Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control. Growing Burden of Heart Disease and Stroke in Canada 2003. [Online]. 2003 [cited 2011 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.cvdinfobase.ca/cvdbook/En/Index.htm

- Statistics Canada. [Online]. 2010 Feb [cited 2011 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.heartandstroke.com/site/c.ikIQLcMWJtE/b.3483991/k.34A8/Statistics.htm#stroke

- Stroke Center. [Online]. 2010 [cited 2011 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.strokecenter.org/patients/stats.htm

- National Stroke Association. What is a Stroke? [Online]. 2004 [cited 2011 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.stroke.org/site/PageServer?pagename=symp

- Atchinson B, Dirette D, editors. Conditions in occupational therapy: Effect on occupational performance. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilson; 2007.

- Bhidayasiri R, Giza C, Waters M. Neurological differential diagnosis: A prioritized approach. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2004.

- Huang. Dysfunction by location: Brain dysfunction: Merck Manual Home Edition. [Online]. 2008 [cited 2011 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/sec06/ch082/ch082b.html

- Legg L, Drummond A, Leonardi-Bee J, Gladman JRF, Corr S, Donkervoort M, et al. Occupational therapy for patients with problems in personal activities of daily living after stroke: Systematic review of randomised trials. British Medical Journal. 2007;335:1-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39343.466863.55.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health well-being and justice through occupation. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2007.

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective. Revised edition. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2002.

- Edmans J, editor. Occupational therapy and stroke. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2010.

- Radomski MV, Trombly-Latham CA, editors. Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction. 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Chapter 9, Assessing abilities and capacities: Cognition; p.260-283.

- Grieve J. Neuropsychology for occupational therapists: Assessment of perception and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993.

- Radomski MV, Trombly-Latham CA, editors. Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction. 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Chapter 38, Stroke; p.1001-1041.

- Alderman N, Burgess PW, Knight C, Henman C. Ecological validity of a simplified version of the multiple errands shopping test. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:31-34. doi: 10.10170 S1355617703910046.

- Dawson DR, Anderson ND, Burgess P, Cooper E, Krpan KM, Stuss DT. Further development of the Multiple Errands Test: Standardized scoring, reliability and ecological validity for the Baycrest version. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2009;90(1):S41-S51. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.07.012.

- Knight C, Alderman N. Development of a simplified version of the multiple errands test for use in hospital settings. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2002;12(3):231-255. doi:10.1080/09602010244000039.

- Rand D, Rukan S, Weiss PL, Katz N. Validation for the Virtual MET as an assessment for executive functions. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2009;19(4):583-602. doi:10.1080/09602010802469074.

- Chamberlain E. Test review. Review of the study Behavioural assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome (BADS). Journal of Occupational Psychology, Employment and Disability. [Online]. 2003 [cited 2011 Feb 22]; 5(2):33-37. Available from: http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/no2-sum-03.pdf#page=38

- Duncan PW, Wallace D, Min Lai S, Johnson D, Embretson S, Jacobs Laster L. The stroke impact scale version 2.0: Evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke. [Online]. 1999 [cited 2011 Feb 22]; 30:2131-2140. Available from: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/30/10/2131

- Fearing V, Law M, Clark J. An Occupational Performance Process Model: Fostering client and therapist alliances. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997;64(1):7-15.

- Gillen G, Burkhardt A. Stroke rehabilitation: A function-based approach. St.Louis: Mosby; 2004.

- Elbaum J, Benson D. Acquired brain injury: An integrative neuro-rehabilitation approach. New York: Springer New York; 2007.

- Leon-Carrion J, editor. Neuropsychological rehabilitation: Fundamentals, innovations, and directions. Delray Beach: GR/St. Lucie Press; 1997. Chapter 15, Rehabilitation of individuals with frontal lobe impairment; p.469-482.

- Crepeau EG, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, editors. Willard & Spackman’s occupational therapy. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Chapter 46, The occupational therapy process; p.478-518.

- Fawcus R. Stroke rehabilitation a collaborative approach. Winnipeg: Blackwell Science; 2000.

- Sandin KJ, Mason KD. Manual of stroke rehabilitation. Toronto: Butterworth Heinemann; 1996.