Course:MEDG550/Student Activities/Smith-Magenis Syndrome

Clinical Features

Smith-Magenis syndrome (SMS) is a genetic disorder characterized by intellectual disability, developmental delay, behavioural abnormalities and distinct facial features. [1] Infants with SMS can have difficulty feeding, failure to gain weight, low muscle tone, prolonged napping or need to be woken up to feed. [2]

Physical Features

Most individuals with SMS have recognizable facial features. Some of the most common features include a wide, square-shaped face, heavy brows, deep-set eyes, short distance between the eyes, and a “tented” upper lip which protrudes from the face. The upper jawbone and nasal bridge tend to be smaller than average, while the forehead and chin appear prominent; this is known as midface retrusion, and becomes more pronounced as children get older. [2] Many people with SMS also have a deep, hoarse voice due to changes in their voice box. Other common physical features associated with SMS include short stature, short fingers and toes, eye and vision problems, middle ear problems, and hearing loss. [1] Less commonly, SMS is associated with cleft lip and palate, seizures, kidney abnormalities, and heart defects. [2]

Neurobehavioral Features

People with SMS tend to be in the range of mild to moderate intellectual disability, as well as have delays in communication and daily living skills. These behavioural problems are usually not recognized until about 18 months of life or after, and continue to change into childhood and adulthood. Typical behavioural problems in children include hyperactivity, aggression, frequent tantrums, and repetitive behaviours. Self-injurious behaviours such as biting, head banging, and pulling out fingernails are also common.[3][2] The majority of people with SMS have sleep disturbances characterized by sleepiness during the day and prolonged awakenings during the night.[4] These sleep disturbances are caused by abnormal regulation of the body’s internal clock, also called circadian rhythm. Circadian rhythm influences many normal functions in our bodies, such as determining when specific hormones are secreted. Some individuals with SMS have a completely inverted circadian rhythm, which causes sleep hormones such a melatonin to be secreted during the day rather than at night.[4] The sleep problems associated with SMS usually continue into adulthood. [2]

Prevalence

Smith-Magenis syndrome was initially estimated to occur in about 1 in 25,000 births.[2] However, SMS may be under-diagnosed due to features that overlap with other disorders, and the syndrome has not been extensively characterized.[3] With recent improvements in genetic testing techniques, more cases have been detected and it is thought that the prevalence may be closer to 1 in 15,000.[2]

Genetics

Genes

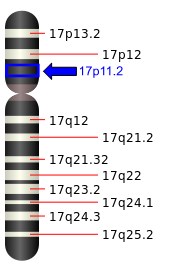

About 95% of SMS cases are caused by a deletion at a specific location on chromosome 17. The specific region that is deleted is referred to as 17p11.2. Although several genes are included in the deleted region, the absence one gene in particular is responsible for most of the behavioural and physical features associated with SMS. This gene is called "RAI1", and makes a protein involved in processes such as brain development, bone growth, metabolism, and circadian rhythm regulation.[5] In approximately 70% of individuals with SMS, the deletion is the same size and includes the same genes.[5] In 5-10% of cases, SMS is caused by a change within the RAI1 gene rather than a deletion of the gene. Individuals with changes that only involve RAI1 still have the typical features associated with SMS, but there are some differences compared to the common deletion. They tend to be more prone to being overweight and have less severe motor delays compared to individuals with the common deletion.[5] In some individuals with the deletion form, the deleted region is larger than in those with the common deletion, which means more genes are missing. Larger deletions are thought to be responsible for some of the less common features of SMS, such as heart defects, kidney problems, and cleft lip and palate.[2]

Inheritance

The genetic changes that lead to SMS are usually de novo, meaning that the change occurred sporadically for the first time in the affected individual, and was not inherited from either parent. Since the de novo genetic changes that lead to SMS usually happen randomly and are relatively uncommon, it is unlikely for more than one person in a family to be affected. If a couple has a child with SMS, the chance of having a second child with the same syndrome is usually less than 1%.[2] In rare cases, one parent may carry a chromosome rearrangement that involves the 17p11.2 region, which significantly increases their chance of having a child with SMS.[2] A person with this chromosome rearrangement has no medical concerns, but there is a chance the parent will pass on the affected chromosome to their child, resulting in SMS in the child.

Diagnosis

SMS can be difficult to diagnose early, as many of the distinct physical and behavioural features are not present until at least 18 months after birth. As a result, many children are not diagnosed until school age when these features become more apparent.[2]

SMS can be diagnosed based on the clinical features, but a genetic test must be performed in order to confirm this. The specific type of SMS diagnosed depends on whether the individual has the deletion form, or a RAI1 gene change. Generally genetic testing for SMS will begin with either array CGH (aCGH) or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), which will both be able to detect the deletion form of SMS.[2] If a deletion is not detected with an aCGH or FISH, the likely next step will be to specifically analyze the RAI1 gene.[2]

Management

Speech and Language

It is recommended that children with SMS begin speech and language therapy as early as possible. Children with SMS usually have delayed communication skills, but their ability to understand language is relatively strong. For this reason, teaching children sign language as an alternate means of communication may be beneficial. In addition, several computer and tablet-based programs are available to assist with communication.[2]

Behavioural Problems

The behavioural problems associated with SMS are often managed though a behaviour support plan, which can include structured school programs and one-on-one education.[2] In some cases, behavioural problems can be managed with medications that decrease hyperactivity, increase attention, or stabilize mood. It has been demonstrated that these while medications may provide short-term benefits, they are largely ineffective for the ongoing management of SMS behaviours.[6]

Sleep Disorders

Managing the sleep disorders associated with SMS can be especially important, as sleep disturbances are thought to increase the severity of behavioural problems.[2] In some cases, melatonin supplements have been shown to greatly improve sleep duration and quality.[4] It may also be necessary to have an enclosed bed system for children with SMS, in order to prevent them from leaving their bedroom unsupervised during the night.[2]

Surveillance

Since many of the symptoms of SMS can be variable and present as time goes on, some of the following may be suggested by the doctor as either routine surveillance or only as needed. For example, monitoring for scoliosis, neurodevelopmental assessments and/or developmental/behavioral consultations with a paediatrician may be useful. Ophthalmology exams and audiologic evaluations may be suggested as surveillance for eye/vision problems and hearing loss, respectively. [2]

Genetic Counseling

Couples who have had a previous child with SMS can have their chromosomes tested to determine if the genetic change was "de novo" or inherited. If it is found to be de novo, the recurrence risk is very low and prenatal diagnosis would not be indicated. In the rare cases when one parent carries a chromosome rearrangement that increases their risk of having a child with SMS, it is possible to perform prenatal diagnosis in future pregnancies to determine if the baby will have SMS.[2] Couples may also choose to pursue preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), in which embryos produced by in vitro fertilization are tested prior to being transferred to the mother.[2] Furthermore, if the parent carries a chromosome rearrangement then chromosome analysis would be indicated for all at-risk family members, which includes other children, siblings, and parents.

Patient Resources

PRISMS - Parents and Researchers Interested in Smith-Magenis Syndrome

Smith-Magenis Syndrome Online Community

Smith-Magenis Syndrome Foundation - UK

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gropman, A. L., Elsea, S., Duncan Jr, W. C., & Smith, A. C. (2007). New developments in Smith-Magenis syndrome (del 17p11. 2). Current Opinion in Neurology, 20(2), 125-134.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Smith ACM, Boyd KE, Elsea SH, et al. Smith-Magenis Syndrome. 2001 Oct 22 [Updated 2012 Jun 28]. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2015. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1310/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Martin, S. C., Wolters, P. L., & Smith, A. C. (2006). Adaptive and maladaptive behavior in children with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 36(4), 541-552.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 De Leersnyder, H. (2006). Inverted rhythm of melatonin secretion in Smith–Magenis syndrome: from symptoms to treatment. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 17(7), 291-298.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dubourg, C., Bonnet-Brilhault, F., Toutain, A., Mignot, C., Jacquette, A., Dieux, A., ... & David, V. (2014). Identification of nine new rai1-truncating mutations in smith-magenis syndrome patients without 17p11. 2 deletions. Molecular syndromology, 5(2), 57.

- ↑ Laje, G., Bernert, R., Morse, R., & Smith, A. (2010, November). Pharmacological treatment of disruptive behavior in Smith–Magenis syndrome. In American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics (Vol. 154, No. 4, pp. 463-468). Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company.