Course:MEDG550/Student Activities/Kleinfelter Syndrome

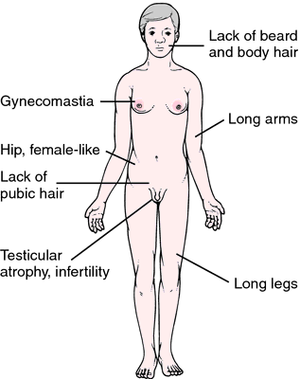

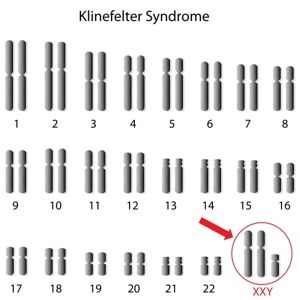

Klinefelter syndrome (KS) is a genetic condition in which a male is born with an extra copy of the X chromosome, resulting in two X chromosomes and one Y chromosome (XXY), instead of the typical one X and one Y (XY). This extra X chromosome results in decreased testicular function and decreased testosterone production, which is the hormone that promotes male sexual development before birth and during puberty. Klinefelter syndrome is characterized by reduced muscle mass, increased breast tissue, small testicles, infertility and reduced body/facial hair. Klinefelter syndrome does not affect an individual's lifespan.

Clinical Features

The presentation of Klinefelter syndrome is variable and physical signs may not present until puberty.

Common features and symptoms include:

- Small testes

- Decreased testosterone, resulting in:

- Delayed puberty

- Breast enlargement (gynecomastia)

- Infertility

- Genital differences

- Undescended testicles (cryptorchidism)

- Opening of the urethra on the underside of the penis (hypospadias)

- Unusually small penis (micropenis)

- Tall stature

- Impaired sperm production (azoospermia or oligospermia)

- Increased risk of breast cancer compared to XY males

Diagnosis

Klinefelter syndrome is diagnosed based on the presence of an extra X chromosome in XY males.

- Karyotype – A karyotype looks at the number, shape, length, and quality of all the chromosomes present in a sample. DNA taken from a blood sample can be used to generate a karyotype. This type of test is definitive and will clearly confirm or deny the diagnosis of Klinefelter syndrome on the basis of the presence or absence of an extra X chromosome.

- Hormone Investigation – As testosterone production is deficient in men with Klinefelter syndrome, a blood or urine sample can reveal abnormal hormone levels that may be associated with Klinefelter syndrome. However, abnormal hormone production can result from a number of causes. This test is therefore an indication of Klinefelter, but not definitely diagnostic.[1]

Klinefelter syndrome can also be diagnosed prenatally by looking at the sex chromosomes from genetic material obtained from fetal cells from an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. These techniques may also use a karyotype to visualize and count all the chromosomes, or do a direct count of only certain chromosomes, including the sex chromosomes. Klinefelter syndrome can also be detected by preimplantation genetic testing for those undergoing assisted reproduction.

Less than 10% of individuals with Klinefelter Syndrome are diagnosed before puberty. The mean age of diagnosis is estimated to be 27 years of age, which can present significant challenges throughout development.[2]

Variations of Klinefelter syndrome

While Klinefelter syndrome refers specifically to the presence of an extra X chromosome in males (XXY), additional X chromosomes (XXXY, XXXXY) result in disorders with similar effects. These conditions are referred to as variants of Klinefelter syndrome. Men with variants of Klinefelter syndrome involving more than one extra X chromosome often have more severe signs and symptoms than men with the classic syndrome. In addition to the above symptoms, men with variants of Klinefelter syndrome may have distinctive facial features, intellectual disability, skeletal abnormalities, poor coordination, and extreme difficulty with speech[3][4]. In general, the severity of the clinical features increases with the presence of more X chromosomes [5].

Prevalence

Klinefelter syndrome is a relatively common condition, affecting 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,000 men.[6] However, it often goes undiagnosed as the symptoms can be mild and vary from person to person. The known signs and symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome are characterized based on the small number of affected males, likely only those seeking medical consultation and displaying more severe clinical features. However, more diagnoses are being made through prenatal and preimplantation genetic testing.

Management

Testosterone treatment

Since testosterone production is compromised in XXY men, hormone supplementation can assist in male sexual development during puberty. Around 12 years of age, androgen (the male sex hormone) replacement therapy ensures appropriate serum concentrations of testosterone, estradiol, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).[7] Though androgen replacement therapy does not treat small testes, gynecomastia or infertility, it encourages normal development of male secondary sex characteristics, normal body proportions, and general improvement in behaviour and work performance.[8] Further, androgen treatment is thought to reduce the risk of breast cancer,[9] which is elevated in men with Klinefelter relative to XY men.[10]

Speech therapy

The development of complex language in men with Klinefelter syndrome is markedly improved with early speech and language therapy.[11]

Physical and occupational therapy

Boys with Klinefelter syndrome may present with reduced muscle tone (hypotonia) and delayed gross motor skills (large movements with arms, legs, feed and/or entire body). In these circumstances, muscle tone, balance, and coordination may be affected and boys would benefit from physical therapy. In cases where fine motor control (fingers, toes, wrists) is impacted or feeding is difficult in infancy, occupational therapy is recommended.[12]

Educational services

Access to additional educational resources requires a thorough psychoeducational examination early on to identify a child's strengths and weaknesses, so that aid can be appropriately allocated. A discussion with a developmental-behavioural pediatrician is recommended, with the aim of planning specific resources and appropriate classroom placement.

Infertility treatment

Genetics

Human genetic information, or DNA, is condensed and packaged into structures called chromosomes. Along each chromosome are smaller segments called genes that provide instructions for producing proteins that are essential in bodily function. Typically, every cell contains 23 pairs of each chromosome, one inherited from each parent. 22 of these chromosomes pairs are shared between males and females, but 23rd pair of chromosomes, termed the sex chromosomes, differ between males and females. Males have one copy of the X chromosome and one copy of the Y chromosome, while females have two copies of the X chromosome. Males with Klinefelter syndrome have an extra copy of the X chromosome, and all of the genes encompassed within it, which is responsible for their clinical features.

The presence of the extra X chromosome occurs by chance through a process called non-disjunction. When sperm and egg cells develop, they undergo a series of cell divisions in a process called meiosis. This process involves replicating and then dividing all of the genetic information in the cell, resulting in each sperm and egg having only one copy of each chromosome (23 total chromosomes). Thus, upon the union of one egg and one sperm during fertilization, the resulting embryo will have 2 copies of each chromosome, making a complete set of 46 chromosomes.

Non-disjunction refers to random errors that can occur during these divisions that cause unequal distribution of chromosomes to sperm and egg cells. Klinefelter syndrome is caused by an extra X chromosome that could have originated from the egg (ie. an egg that had two X chromosomes joining with a normal sperm with one Y chromosome) or from the sperm (ie. a sperm that had both an X and Y chromosome joining with a normal egg with one X chromosome), resulting in an embryo that is XXY.

Genetic Counselling

Inheritance

Non-disjunction is a sporadic, random event that causes Klinefelter syndrome and is therefore not inherited. Having an affected child with Klinefelter syndrome does not increase the risk of having another affected child above the baseline population risk. Men with Klinefelter syndrome who wish to father children through assisted reproductive technology are not at increased risk of producing sperm with extra copies of the X chromosome[13].

Infertility and Assisted Reproductive Technology

Achieving a pregnancy was previously not thought possible in men with Klinefelter syndrome, because most of these men do not have sperm in their semen (azoospermia). However, through assisted reproductive technology, doctors can find sperm by means of testicular sperm extraction (TESE). TESE is a surgical procedure that involves taking a microscopic testicular biopsy near the site of sperm production and extracting sperm from the sample. The sperm can then be used to fertilize an egg in a procedure called in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). ICSI allows for the direct injection of a sperm into the cytoplasm of an egg, which is then grown in the laboratory for several days and implanted into a woman's uterus to establish a pregnancy.[14]

Psychosocial Components

Due to the symptoms associated with Klinefelter Syndrome and the later average age of diagnosis, individuals with Klinefelter Syndrome can face many personal and social challenges. Many individuals born with Klinefelter Syndrome report feeling different growing up without knowing why, prior to a diagnosis. It is also possible for those with Klinefelter Syndrome to feel as though they do not fit into either category of male or female. This can cause confusion and frustration, especially in relation to self-acceptance and gender identity. People with Klinefelter Syndrome may decide to identify as male, female, non-binary, or intersex depending on what feels right to them. In some cases, a diagnosis can provide a sense of relief to those with Klinefelter Syndrome, as it provides an explanation for their experiences growing up. There have been reports of increased anxiety and depression in those with Klinefelter Syndrome, as well as higher BMIs, which can contribute to low self-esteem. It can also be difficult for parents of children with Klinefelter Syndrome to understand and adapt to their child's identity, as many parents struggle with differences in fertility and masculinity associated with this diagnosis.[2]

Resources

For more information about Klinefelter syndrome, visit:

For patient support groups, visit:

- The Association for X and Y Chromosome Variations (AXYS)

- Klinefelter Syndrome Global Support Group

- The American Association for Klinefelter Syndrome Information and Support (AAKSIS)

- Living with XXY

To find a genetics specialist, please visit www.cagc-accg.ca (Canada) or www.nsgc.org (United States).

References

- ↑ Mayo Clinic, 2016 https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/klinefelter-syndrome/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353954

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hanna, Esmee Sinead; Cheetham, Tim; Fearon, Kristine (November 26 2019). "The Lived Experience of Klinefelter Syndrome: A Narrative Review of the Literature". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 10: 5 – via Frontiers. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Visootsak J, Aylstock M, Graham JM Jr. Klinefelter syndrome and its variants: an update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001 Dec;40(12):639-51. Review.

- ↑ Frühmesser A, Kotzot D. Chromosomal variants in klinefelter syndrome. Sex Dev. 2011;5(3):109-23. doi: 10.1159/000327324. Epub 2011 Apr 29. Review.

- ↑ Tartaglia N, Ayari N, Howell S, D'Epagnier C, Zeitler P. 48,XXYY, 48,XXXY and 49,XXXXY syndromes: not just variants of Klinefelter syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2011 Jun;100(6):851-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02235.x. Epub 2011 Apr 8. Review.

- ↑ Genetics Home Reference, 2013 https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/klinefelter-syndrome#statistics

- ↑ Visootsak J, Graham Jr J. Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006 Oct;1:42

- ↑ Nielsen J, Pelsen B, Sorensen K. Follow-up of 30 Klinefelter males treated with testosterone. Clin Genet. 1988;33:262–269

- ↑ Kocar IH, Yesilova Z, Ozata M, Turan M, Sengul A, Ozdemir I. The effect of testosterone replacement treatment on immunological features of patients with Klinefelter's syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:448–452

- ↑ Brinton LA. Breast cancer risk among patients with Klinefelter syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2011 Jun; 100(6): 814-8

- ↑ Visootsak J, Graham Jr J. Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006 Oct;1:42

- ↑ Visootsak J, Graham Jr J. Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006 Oct;1:42

- ↑ Bergère M, Wainer R, Nataf V, et al. Biopsied testis cells of four 47,XXY patients: fluorescence in‐situ hybridization and ICSI results. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:32‐37

- ↑ Tournaye H, Camus M, Vandervorst M, Nagy Z, Joris H, Van Steirteghem A, Devroey P. Surgical sperm retrieval for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Int J Androl. 1997; 20 Sppl 3:69-73