Course:MEDG550/Student Activities/Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis

Iron is an essential element that is used by the blood to transport oxygen around a person's body. Hemochromatosis is a disease that is caused by too much iron in the body. When there is too much iron, the body will store it in different tissues or organs which causes problems for the affected individual[1]. There are two types of hemochromatosis:

- Hereditary hemochromatosis is an inherited condition which causes over-absorption of iron in the digestive tract. Because genes are passed on through families, you have a greater risk of developing hemochromatosis if you already have an affected family member. [2]

- Secondary hemochromatosis is not due to a gene change. The disease develops due to complications from other health conditions such as thalassemia. It can also be caused by excessive blood transfusions, such as those required as treatment for individuals with hemophilia.[2]

Clinical Features

Individuals may initially present with general and non-specific symptoms such as:

- fatigue

- weight loss

- joint pain

- weakness

- loss of energy

Physicians may make a diagnosis of hemochromatosis based on a physical exam (e.g. enlarged spleen, skin colour changes) or a blood test which shows elevated iron or transferrin saturation levels.[2] Hereditary hemochromatosis (HFE-HH) can be classified as clinical, biochemical, or non-expressed. [3]

- Clinical HFE-HH is characterized by excessive storage of iron in the liver, skin, pancreas, heart, and joints. If untreated, individuals can experience abdominal pain, weakness, and weight loss. If serum ferritin (iron in the blood) is higher than 1000 ng/mL individuals are at a higher risk for developing liver cirrhosis. Other complications include diabetes, congestive heart failure, and arthritis. Clinical HFE-HH is more common in men than women. [3]

- Biochemical HFE-HH is diagnosed when the only symptom of iron overload is increased serum ferritin concentration and increased transferrin-iron saturation.[3]

- In someone with non-expressing HFE-HH, there are no clinical or biochemical signs of the condition, despite the presence of disease-causing mutations. [3]

The complications seen in clinical HFE-HH are the result of gradual iron overload. Iron that is over-absorbed by the intestines is slowly stored into tissues and organs. If the iron levels present in these tissues reaches a high enough threshold, the individual may develop hemochromatosis. Clinical symptoms of hemochromatosis do not usually begin until the 4th-6th decades of life. Possible complications of untreated hemochromatosis include organ damage, liver failure, liver cirrhosis (scarring and damage of the liver that affects its function), diabetes, heart problems, and skin bronzing. [4]

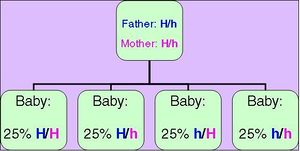

Inheritance

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disease, which means that you must inherit a copy of the gene change from both your mother and your father to be affected by the condition. If you have only one gene change, you are known as a heterozygote, or a carrier. Men and women are equally likely to be affected by hemochromatosis, however men are more likely to develop severe clinical complications as a result of the disease.[3] There are a number of types of hereditary hemochromatosis which are classified based on the gene that is affected. Most cases of adult-onset hemochromatosis are due to changes in the HFE gene. However, there can also be changes in a number of other genes such as HJV and HFE25 (which cause juvenile hemochromatosis), SLC40A1 (which causes autosomal dominant hemochromatosis), and TFR2 (which causes a different form of autosomal recessive hemochromatosis).[5]

Prevalence

Hemochromatosis is one of the most common autosomal recessive diseases in White populations. It is estimated that 1 in 10 persons of European descent are carriers of a hemochromatosis mutation[6], and between 1 in 200 to 1 in 500 individuals in this population have two copies of the hemochromatosis gene mutation.[3]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hemochromatosis may be made based on a combination of the clinical features, blood tests, liver biopsy and/or genetic testing.[7] Elevated levels of transferrin saturation with no other identifiable cause is considered to be the earliest sign of the disease.[7] By young adulthood, individuals will have elevated transferrin saturation, serum ferritin levels and abnormal liver function tests.[7] Measuring serum iron concentration alone is not considered to be a reliable marker due to natural changes throughout the day.[7] Liver biopsies provide information about the level of iron overload and whether liver cirrhosis has developed.[7]

If the physician suspects hereditary hemochromatosis (or you have a family history of hemochromatosis), they will start by ordering a blood test to look at iron in your blood, then, depending on the results, they may request a genetic test for the gene that is most commonly changed in adult onset hemochromatosis.[8]

Treatment and Management

Patients whose hemochromatosis has progressed to severe complications such as organ damage or liver failure have shortened life spans, however early diagnosis and treatment enables individuals with hemochromatosis to prevent these complications and have normal life expectancy.[5]

Individuals diagnosed with hemochromatosis have three options for treatment:[8]

- Iron depletion therapy (AKA phlebotomy): similar to blood donation, a needle will be inserted to remove some blood. This decreases the amount of iron in your body and prevents the overload in your tissues.

- Erythrocytapherisis: may or may not be offered based on availability and patient needs.

- Iron-chelating drugs (second-line treatment because of side-effects): medications which attach to extra iron and make it easier for the body to get rid of (target ferritin levels higher than treatment options 1 and 2).

There are two stages of treatment for treatments 1 and 2:[8]

- Induction: occurs weekly or biweekly to eventually reach a target ferritin (iron) level of 50 µg/L

- Maintenance: usually 2-6 times per year, for the life of the affected person, to maintain a target ferritin level of 50-100 µg/L

Individuals with elevated serum ferritin levels may also consider blood donation as a method of maintaining iron levels when they are in the maintenance stage. [9]

In individuals who already have liver cirrhosis, routine screening for hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is conducted every 6 months.[8] Patients with biochemical HFE-HH are typically checked every 6 to 12 months to ensure that the iron levels in their blood aren’t too high. [3]

Individuals with hemochromatosis are advised to avoid sources of additional iron. These include medicinal and mineral iron supplements, excess vitamin C, and uncooked seafood. Patients who have liver damage are advised to avoid alcohol consumption. Secondary complications can also be avoided by ensuring that individuals are vaccinated against hepatitis A and B. [3][9]

Genetic Counselling

Since hereditary hemochromatosis is a genetic condition, family members of a newly diagnosed person are at risk of also being affected, or they may be carriers of the gene change. Once the family variant is known, it is possible to offer genetic testing to at-risk individuals. The affected individual’s parents are mostly likely unaffected mutation carriers, although it is possible that they could be affected but undiagnosed. The affected individual’s siblings could be carriers or affected, and should be offered testing. In addition, an affected individual’s children will inherit the mutation, or could possibly have hereditary hemochromatosis if both of their parents are affected or carriers.[3] Genetic testing of children under the age of 18 is not recommended due to potential concerns about informed consent and genetic discrimination. [10]

As hemochromatosis is a very common disease in White populations, population screening for the HFE mutation has been suggested. Early diagnosis allows for appropriate treatment and prevention of severe complications. However, many individuals with a homozygous mutation will never develop disease symptoms or hemochromatosis, and there are concerns that population screening could lead to undo anxiety as well as potential health and employment discrimination.[4] In addition, as hemochromatosis is an adult onset disease that has a very effective treatment, prenatal screening for hemochromatosis is not currently offered or recommended.[4]

Resources

There are several organizations in Canada and the United States that provide information and support to individuals and families affected by hemochromatosis. They also strive to raise awareness of hemochromatosis.

Canadian Hemochromatosis Society

Hemochromatosis Information Society

References

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff (Jan 9, 2025). "Hemochromatosis". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved Jan 31, 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bacon BR. Iron overload (hemochromatosis) In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 219.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Barton JC, Parker CJ. HFE-Related Hemochromatosis. 2000 Apr 3 [Updated 2024 Apr 11]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1440/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sturhmann, M., Graf, N., Dork, T., Schmidtke, J. 2000. Mutation screening for prenatal and presymptomatic diagnosis: cystic fibrosis and haemochromatosis. European Journal of Pediatrics. 159(3):S186-S191

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. MIM Number:235200 {Date last edited}: Sept 28, 2012. World Wide Web URL: http://omim.org/entry/235200

- ↑ Alberta Precision Laboratories (Jul 25, 2022). "HFE-Associated Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HFE-HH): Information for Ordering Providers" (PDF). Alberta Health Services. Retrieved Jan 31, 2025.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Powell, L. George, K., McDonnell, S., Kowdley, K. (1998) Diagnosis of Hemochromatosis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 129, 925-931.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Zoller, H., Schaefer, B., Vanclooster, A., Griffiths, B., Bardou-Jacquet, E., Corradini, E., Porto, G., Ryan, J., & Cornberg, M. (2022). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on haemochromatosis. Journal of Hepatology, 77(2), 479–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.03.033

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Canadian Hemochromatosis Society: Treatment Recommendations. http://www.toomuchiron.ca/hemochromatosis/treatment/

- ↑ Beaton MD, Adams PC. The myths and realities of hemochromatosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007 February; 21(2): 101–104.