Course:LING300/Scrambling in Japanese

Introduction

Scrambling is a free word order phenomenon that is responsible for the syntactic reordering of constituents in the structure.[1] In languages like Japanese, where word order is flexible, the canonical word order of SOV can be scrambled to OSV. [2] It has been proposed that languages divide into those that are configurational and non-configurational.[3] Configurational languages are structured in a way where the subject and object are in asymmetrical relation to the verb. On the other hand, non-configurational languages are said to have a 'flat structure' whereby all phrases are in a symmetrical relation to the verb. Therefore, as the Japanese language is considered to be a non-configurational language, the free word order enables scrambling.

Two kinds of syntactic reordering is apparent in Japanese. The first kind is "short distance" (SD) scrambling, where the scrambling occurs in the same clause or tense phrase. The second kind is "long distance" (LD) scrambling, where scrambled phrases such as determiner phrases (DP) and prepositional phrases (PP) moves out of the clause it is generated, landing in the initial position of a higher clause.[4]

Examples

The following abbreviations are used: NOM = Nominative Case, ACC = Accusative Case, GEN = Genitive Case. Koto is a sentence final particle added to the end of sentences in order to make them sound more natural.[2]

The basic word order sentence of SOV in (1a) and the scrambled word order OSV in (1b) convey the same propositional meaning.

(1.a) Taroo-ga piza-o tabeta

Taro-NOM pizza-ACC ate

'Taro ate pizza.'[5]

(1.b) piza-o Taroo-ga tabeta

pizza-ACC Taro-NOM ate

'Taro ate pizza.'[5]

Short Distance Scrambling

Short distance scrambling (or clause-internal scrambling) involves the object to move to the clause-initial position. A clause refers to a sentence-like structure that is commonly described as having a "subject" and "predicate".[6] The clause-initial position is the specifier to the tense phrase (Spec, TP), which locates the subject of the sentence. The example shows the canonical word order in (2a) to a DP sono hon-o 'that book-ACC' scrambling within the same tense phrase in (2b).

(2.a) [CP[TP Taroo-ga sono hon-o katta] koto]

Taro-NOM that book-ACC bought fact

'Taro bought that book.'[7]

(2.b) [CP[TP sono hon-oi [TP Taroo-ga ti katta]] koto]

that book-ACC Taro-NOM bought fact

'That book, Taro bought.'[7]

Long Distance Scrambling

Long distance scrambling involves the object to move out of the clause. The example shows the canonical word order in (3a) to a DP sono hon-o 'that book-ACC' scrambling outside of the embedded CP (complementizer phrase) clause in (3b) to the clause initial position of the tense phrase in the matrix clause.

(3.a) [CP[TP Hanako-ga [CP[TP Taroo-ga sono hon-o katta to omotteiru]]] koto]

Hanako-NOM Taro-NOM that book-ACC bought that think fact

'Hanako thinks that Taro bought that book.'[7]

(3.b) [CP[TP sono hon-o [TP Hanako-ga [CP[TP Taroo-ga ti katta to omotteiru]]] koto]

that book-ACC Hanako-NOM Taro-NOM bought that think koto

'That book, Hanako thinks that Taro bought ti.'[7]

Short Distance Scrambling

Movement Representation

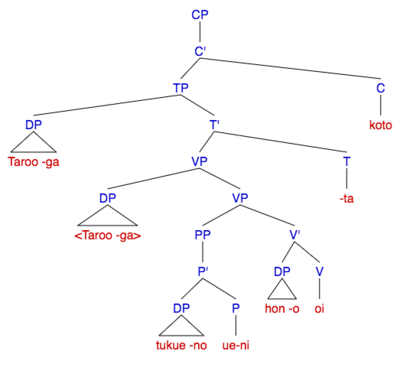

Phrases such as DP, PP and CP can move to a clause-initial position. The following examples below illustrate SD scrambling which is scrambling that occurs within the same clause or the tense phrase (TP).[2] (4a) shows the canonical word ordering with the subject Taro-ga 'Taro-NOM' in Spec, TP and the object hon-o 'book' in the complementizer position of the verb (Comp, VP) oita 'put'.

Note: X-Bar notations are used in the tree constructions below. Phrase labelling with angle brackets (<...>) illustrates a moved constituent.

(4.a) [CP[TP Taroo-ga tukue-no ue-ni hon-o oita] koto]

Taro-NOM desk-GEN top-on hon-ACC put fact

'Taro put the book on the desk.'[2]

In (4b), the object hon-o 'book-ACC' scrambles to the clause-initial position which is Spec, TP. An additional layer is added in Spec, TP to account for the moved element. The propositional meaning of the sentence remains the same, namely that 'Taro put the book on the desk'.

(4.b)[CP[TP hon-o [TP Taroo-ga tukue-no ue-ni ti oita]] koto]

book-ACC Taro-NOM desk-GEN top-on put fact

'The booki, Taro put ti on the desk.'[2]

In (4c), the PP 'on top of the desk' is scrambles to the clause-initial position, which is Spec, TP. Similar to (4b), an additional layer is added in Spec, TP to account for the moved PP. The propositional meaning of the sentence also remains the same, namely that 'Taro put the book on the desk.'

(4.c)[CP[TP tukue-no ue-ni [TP Taroo-ga ti oita]] koto]

desk-GEN top-on Taro-NOM put fact

'On top of the deski, Taro put the book ti.'[2]

Analysis

It has been argued that Japanese has three types of movement: A-movement, A'-movement and scrambling.[8] A-movement is movement of the subject raising kind where there is an argument shift.[9] A'-movement is movement of the is wh-movement kind, where there is an adjunction to an XP.[9] The kind of movement that occurs in SD scrambling is said to be motivated by A-movement due to its affects on binding relations, the Weak Cross-Over (WCO) phenomenon and Superiority Effects. While Miyagawa has argued SD scrambling to be motivated by A-movement due to EPP features[10], the analysis below is provided by Saito[8].

Binding Relations in A-Movement

In Principle A of the Binding Theory, it is stated that anaphor must be bound in its domain. In (5), the anaphor is otagai-no 'each other-GEN' and the antecedent DP is karera-no 'them-ACC', with both elements co-referencing each other (seen with the co-indexation marked with "k"). In (5a), the object karera-o 'them-ACC' cannot c-command the anaphor otagai-no 'each other-GEN' because the sister of karera-o 'them-ACC' does not dominate otagai-no 'each other-GEN'.[7]

(5.a)[CP[TP otagai-nok sensei-ga karera-ok hihansita] koto]

each other-GEN teacher-NOM them-ACC criticized fact

'Each other'sk teachers criticized themk.'[7]

However, once karera-o 'them-ACC' scrambles to the front of the clause, the antecedent DP karera-o 'them-ACC' can c-command the anaphor DP otagai-no 'each other-GEN' since the sister of karera-o 'them-ACC' is TP, which dominates otagai-no 'each other-GEN'. The anaphor otagai-no 'each other-GEN' is also bound in its domain because the smallest XP that contains the subject karera-o 'them-ACC' and the anaphor is TP. This shows that scrambling is comparable to subject raising since Principle A in Binding Theory illustrates an A-movement property of scrambling.[8]

(5.b)[CP[TP karera-ok [TP otagai-nok sensei-ga tk hihansita]] koto]

them-ACC each other-GEN teacher-NOM criticized fact

'Themk, each other'sk teachers criticized tk.'[7]

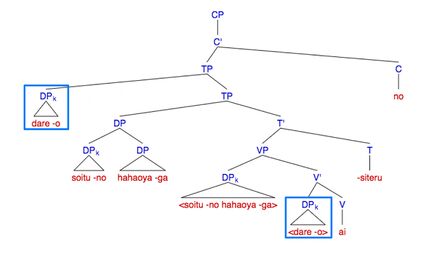

Weak Cross-Over (WCO) and A-Movement

Weak cross-over occurs when a wh-movement crosses over a c-commanding phrase containing a pronoun that is binds.[11] In Japanese, overt pronouns such as kare ‘he’ cannot usually be construed as bound variables (because it must take a subject DP as its antecedent), however, it has been argued that soitu ‘the guy-GEN’ is interpreted as a bound variable.[12] Using the overt pronoun soitu 'the guy', the example in (6a) illustrates a violation of weak cross-over. In (6a), the antecedent DPwh dare-o 'who-ACC' is unable to bind the pronoun soitu-no 'the guy-GEN' because dare-o 'who-ACC' does not c-command the co-indexed pronoun soitu-no 'the guy-GEN'.

(6.a) [CP[TP Soitu-nok hahoya-ga dare-ok aisiteru] no]

the guy-GEN mother-NOM who-ACC love Q

'Hisk mother loves whok.'[12]

However, in (6b), the violation of weak cross-over can be neutralized when the DPwh dare-o 'who-ACC' scrambles to the clause-initial position, namely at Spec, TP. Scrambling allows the DP dare-o 'who-ACC' to c-command the pronoun soitu-no 'the guy-GEN'.

(6.b) [CP[TP Dare-ok [TP soitu-nok hahaoya-ga tk aisiteru]] no]

who-ACC the guy-GEN mother-NOM love Q

'Whok, his mother loves tk.'[12]

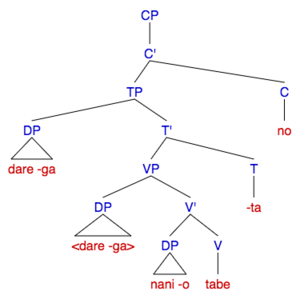

Superiority Effects

Scrambling is considered a movement process in which a scrambled phrase moves to Spec, TP, just as subject raising does. This is because A-movement is assumed to have the landing site Spec, TP. Moreover, the lack of superiority effects provides evidence that the landing site is indeed Spec, TP.[8] The superiority condition is applied when there are multiple wh-phrases in a question and has an instance of the 'attract closet' principle which regulates what happens when there are two potential candidates for movement.[13] The attract closest principle states that only the closest potential candidate can move to an attracting head which selects for it.[13] Consider (7) which shows that wh-phrases cannot move over a c-commanding wh-phrase because 'wh2' is not a wh-phrase closest to Spec, CP in the matrix clause:

(7) * wh2 . . .X . . .wh1 . . .wh2

(8a) below shows the baseline wh-question prior to scrambling the wh-phrase nani-o 'what-ACC'.

(8.a) [CP[TP Dare-ga nani-o tabeta] no]

who-NOM what-ACC ate Q

'Who ate what?'[8]

In (8b), the object wh-phrase nani-o 'what-ACC' scrambles to Spec, TP just like subject raising.[8] Moreover, the wh-phrase nani-o 'what-ACC' can cross the wh-phrase dare-ga 'who-NOM', while keeping the propositional meaning of the question the same.

(8.b) [CP[TP Nani-o [TP dare-ga ti tabeta]] no]

what-ACC who-NOM ate Q

'Who ate what ti?'[8]

Useful Definitions

Definitions relating to Binding Relations

- Anaphors

- refers to reflexive pronouns and reciprocals.[14]

- Principle A on Binding Conditions

- an anaphor must be bound in its domain.[15]

- Bound

- A DP is bound (by its antecedent) just in case there is a c-commanding DP which has the same index.[15]

- Antecedent

- A DP on which the reference of a pronominal expression (like anaphors) depends.[14]

- Domain

- the domain of a DP anaphor is the smallest XP with a subject that contains the DP.[16]

- C-command

- Node X c-commands node Y if a sister of X dominates Y.[17]

Definitions relating to Weak Cross-Over (WCO)

- Wh-movement

- movement of a "wh-phrase" to clause-initial position[18]

References

- ↑ Ross, John R. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Yoshimura, Noriko (2017). Handbook of Japanese Syntax. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 807.

- ↑ Miyagawa, Shigeru (2001). Ken Hale: A Life in Language. The MIT Press Direct. pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Yoshimura, Noriko (2017). Handbook of Japanese Syntax. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 808.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Imamura, Satoshi; Sato, Yohei; Koizumi, Masatoshi (2016). "The Processing Cost of Scrambling and Topicalization in Japanese". Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 3.

- ↑ Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 87.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Saito, Mamoru (1992). "Long Distance Scrambling in Japanese". Journal of East Asia Linguistics. 1:1: 74–75.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Mizuguchi, Manabu (2010). "On A- and A'-movement Properties of Scrambling". English Linguistics. 27:1: 60–79.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 230.

- ↑ Miyagawa, Shigeru (2001). "The EPP, Scrambling, and wh-in-situ". Ken Hale: A life in language – via MIT Press Direct.

- ↑ Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 320.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Saito, Mamoru (1992). "Long Distance Scrambling In Japanese". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 1:1: 73.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 296.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 159.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 168.

- ↑ Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 171.

- ↑ Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 161.

- ↑ Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 260.