Course:LFS350/Projects/2014W1/T13/Report

Executive Summary

This project was a multifaceted endeavour involving the engagement of our eight-team members and a community partner, The Richmond Food Security Society. Our role in this partnership was to conduct an ethnographic study. We interviewed two Chinese-Canadians involved in the food system, who have lived or worked in Richmond, to investigate how they understand the connections between food security and civic engagement. For this study, we obtained our sample through a modified snowball sampling technique. Once our sample was defined, we conducted open-ended interviews and carried out an inductive data analysis to reveal common trends in these individuals’ perceptions of civic engagement and its relation to food security.

We conducted interviews with two civilly engaged individuals engaged in the city of Richmond, BC. Ian Lai, is the program director of The Richmond Schoolyard Society. Karen Dar Woon is a culinary professional and a former board member of the Sharing Farm Society. Both participants identified problems in their food system and have taken initiative to address these issues through civic engagement.

There is a large immigrant population in Richmond that faces unique challenges in regards to food security. They also face barriers to becoming civically engaged upon their arrival in Canada. Our findings suggest language barriers are a big issue for new immigrants. Our results indicate a need for stronger supports to encourage civic engagement among immigrants. We speculate that becoming civically engaged could enhance food security in these communities.

The limitations of this study can be attributed to the very specific inclusion requirements outlined for participants. In addition, we were unable to achieve our goal of four interviews because we had appointments cancelled due to unforeseen circumstances. This lead to a sample size that was smaller than intended. The small samples size increases the bias and decreases the credibility of our results. Our findings are not representative of the Chinese-Canadian population overall.

Introduction

Food security is “access by all people, at all times, to food that is safe, nutritionally adequate and personally acceptable and which is obtained in a manner that respects human dignity” (Koc & Welsh, 2002, p. 4). Food security is an important determinant to people’s health and well-being. One’s relationship with food is an key aspect of cultural and individual identity and is determined by complex interaction between the cultural arrangement of our society, the organization of food systems, and social policies (Koc & Welsh, 2002). In the last four decades, the shift to industrial agriculture has increased the distance between people and their food, led to a loss of local knowledge and cultural diversity (Sage, 2012; Wilkins, 2005). We are producing more food than ever before but there are still many people who lack food security.

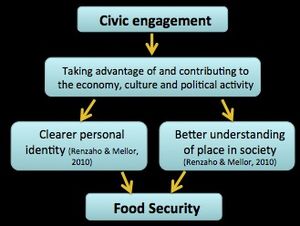

Vulnerable members of society are most at risk of food insecurity (Koc & Welsh). New immigrants are often vulnerable and isolated because of economic stress, language barriers, low self-esteem, and cultural and religious barriers (Renzaho & Mellor, 2010). The limited availability and high cost of traditional food items, coupled with a pressure to assimilate can exacerbate food insecurity for immigrants (Renzaho & Mellor, 2010). The challenges faced by new immigrants to establish a sense of belonging in their new home can hamper their well-being (Renzaho & Mellor, 2010). The ability to take advantage of and contribute to society is important to personal identity and understanding of how you fit into society (Renzaho & Mellor, 2010).

Civic engagement is effort of an individual or collective group to recognize and address issues of public concern. Civically engaged individuals work to enhance the quality of life in a community (Ehrlich, 2000). Part of being civically engaged means recognizing oneself as part of a larger social fabric (Erlich, 2000). For this reason, becoming civically engaged can greatly enhance one’s feeling of inclusion. Empowering immigrants to contribute can help them develop their dynamic personal and cultural identity and by extension, make them more food secure.

The Richmond Food Security Society (RFSS) is an organization that hopes to enhance food security and justice (Richmond Food Security Society, 2014). Chinese Canadians alone represent 49% of Richmond’s population (City of Richmond, 2014). Because of the very large number of immigrants in Richmond, the RFSS faces unique challenges in trying to fulfill their mandate of ensuring “access to nutritious, safe, personally acceptable and culturally appropriate foods, produced in ways that are environmentally sound and socially just" (Richmond Food Security Society, 2014). We constructed a food system diagram to illustrate the interactions between the RFSS and the food system at large. As this diagram indicates, the RFSS’s influence is most significant in the areas of food policy and management.

We are an interdisciplinary group of students at the University of British Columbia enrolled in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems. We conducted this ethnographic study with the RFSS that explored the civic engagement of two Chinese Canadians who have lived and worked in Richmond. We constructed a narrative asking the question: How is food security related, connected to and/or relevant to the civic engagement of Chinese-Canadians? We hope that the RFSS can utilize this narrative to inform their programming in the future in order to better assist new immigrants in overcoming the challenges of becoming civically involved and food secure.

Research Methods

Study Description

We conducted an ethnographic study to build a narrative around the connections between food security and the civic engagement of two Chinese-Canadians working in Richmond. Ethnography is defined as the study of how culture influences peoples’ behaviours, opinions, and understanding of events or issues through personal accounts (Hammersley and Atkinson, 2007). We utilized this method because of its appropriateness for exploring how culture and food security are connected to the civic engagement of Chinese-Canadians. Conducting ethnographic interviews and documenting the stories of our participants gave us detailed, and personal data that would not have been provided by quantitative methods.

A disadvantage of this type of study is that it is subjective, which means the results are not necessarily applicable to a larger population (Singer, 2009).

Participants

The participants in our study include two Chinese-Canadians who have lived and worked in Richmond, with a history of civic engagement in their local food system.

Communication and Ethics

Throughout this project, communicating with our community partner and participants was done through email and in-person meetings. We used email predominantly for arranging interviews and keeping our community partner up-to-date on our progress.

To ensure that our research was carried out ethically, every part of our study was designed with the participant in mind. Prior to the in-person interviews, participants were emailed the question set. They were also provided a copy of the consent form which they would be asked to sign. Before conducting the interviews all participants were required to give informed consent. We used the consent form provided to us by the LFS 350 team. If participants did not with to be recorded on video, we were prepared to conduct interviews using audio recording devices instead. We carried out interviews at a time convenient for our participants. We made sure that participants were aware that they were not obliged to answer any questions and encouraged to skip questions they preferred not to answer.

Sampling Methods

Prior to identifying a sample, a set of criteria was developed to screen potential candidates. Our inclusion criteria required participants to be long term Chinese-Canadian immigrants who had lived in Canada for a minimum of ten years, and were currently living in Richmond. We also required our participants to have a history of civic engagement in their local food system. Unfortunately, given our response rate, we had to expand our criteria after data collection. Our new criteria includes any person of Chinese descent who has lived in Richmond, is currently working or volunteering in Richmond and has a long history of civic engagement in their local food system.

We utilized a snowball sampling technique. This method involves asking the participants to name other people they know that could be potential candidates (Goodman, 1961). This technique is useful when the objective is to look at a population that may be difficult to access by other means (Goodman, 1961). We obtained our first interview candidate, Ian Lai by talking to an LFS colleague who thought he would be an appropriate participant. The RFSS also provided us with a list of people to contact for an interview. We emailed five individuals and heard back from three but were only able to secure an interview with one. We tried using the snowball sampling technique however, our interviewees were unable to provide us with more contacts.

The disadvantages of snowball sampling are that this method requires the research group to be continuously involved in the entire process of obtaining potential participants, and following up with referrals (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). This can be a time consuming. Furthermore, the sample produced through this process is not random, and thus biases may be present (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981).

Data Collection

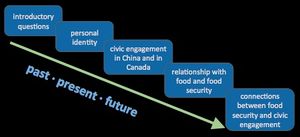

To construct a narrative, we conducted open-ended interviews. This technique was ideal for gathering opinions, ideas and personal experiences from participants (Monroe, 2002). Our interviews were thirty to forty minutes in length and were conducted in person at a location and time agreed upon by the interviewers and participants. Each interview was carried out by two team members and formatted as an open dialogue rather than a question and answer session. We designed the questions to guide a conversation on our topics of interest (Figure 2). The interviews were video recorded.

Data Analysis

Because of the qualitative nature of our data, we used inductive data analysis. This type of analysis involves intensive review of raw data to generate common trends and themes (Thomas, 2006). Upon conducting the interviews we analyzed and compared them to each other, looking for common themes as well as differences. We also compared them to the literature we reviewed on the topic.

Key Sources of Information

We drew on two different sources for information throughout the research process. To develop background knowledge, we carried out a literature review. We also utilized the expertise of our community partner, Colin Dring. He provided us with resources that enhanced our understanding of the topic and community, provided us with our initial interview candidates, and gave us recommendations on contacting participants, and conducting our interviews.

Additional Resources Needed

We needed a video camera and video editing software.

Findings

We interviewed two individuals, Ian Lai and Karen Dar Woon. Ian Lai teaches elementary school children about food systems. Karen is a board member of the Sharing Farm Society, an organization working with farms and the Richmond Food Bank to help in the distribution of food. From these interviews, we were able to see connections between civic engagement and food security.

Both of our participants identified the challenges that face new immigrants in becoming civically engaged. Ian Lai mentioned that the stresses caused the challenges of resettling coupled with language barriers can impair immigrants' ability to become engaged. He suggested that providing food systems education for children of different cultural backgrounds could help them and their parents overcome these obstacles. Karen Dar Woon had similar recommendations. She suggested gathering different multicultural groups to work together through gardening and volunteering to improve their understanding of the local food system. This would emphasize the use of food to connect people and communities. By decreasing the distance between people and their food, these programs might reduce improper distribution of food and thus enhance food security for the community. From these two interviews, there is a clear consensus that civic engagement can be used as a method of improving food security for new immigrants.

Our deliverable for this project was a video, depicting the narrative we constructed around these issues.

Discussion

We constructed a wordle using our interview transcripts to create a visual that illustrates the key themes that emerged from our discussions with Ian Lai and Karen Dar Woon (Figure 3).

Within our findings, we drew connections between the ideas expressed by both participants:

- Despite their very different backgrounds, both individuals we interviewed came from families that put a strong emphasis on food. We speculate that their exposure to food from a young age could have been a critical factor in their civic engagement with the food system as adults. Both participants expressed their belief in the importance of teaching food skills and literacy to young children in order to enhance food security. These findings are in line with McCullum et al.’s (2005) assertion that elementary school food programs are a good way to build community food security.

- The participants highlighted the importance of learning by doing. Both believed that getting involved and taking part in learning experiences within the community enhances people’s food security. Ian Lai believes that civic engagement allows immigrants to “talk about food” which improves their food security. Similarly, Karen Dar Woon saw the connection between food security and civic engagement because “actually learning about food through working with food” is the best way to enhance an individual’s food security. This finding is in line with our hypothesis. It is also a key point for the RFSS to consider when engaging immigrants in the future. Furthermore, it is in accordance with the LFS 350 course philosophy, which emphasizes participatory learning.

- Both participants implied that language was the biggest barrier for immigrant civic engagement. It is likely because of this that both interviewees observed the tendency for people within the same ethnic and language group to associate more closely in the context of civic engagement. It is interesting to note the disparity in the participants’ reactions to this fact. Karen Dar Woon felt that it “provides [a] vehicle for smaller sub-communities to get to know each other.” Ian Lai, in contrast, was critical of this ethnic cliquing and articulated his belief that we should be working to bridge the gaps between these communities, “so that we’re working multiculturally instead of monoculturally.”

- Ian Lai and Karen Dar Woon both said that they thought accessability to culturally appropriate foods was no longer an issue for immigrants in Richmond. Both indeviduals reminisced about how years ago, Chinese ingredients were not as readily available as they are today. The appropriateness of food is an important aspect of food secuity according to the AAASS definition that we have discussed in the LFS core series (Think&Eat Green @ School, 2012). This is a critical result because it indicates that the RFSS should be focusing on the other elements of food security (Affordability, Availability, Accessibility, Safety, and Sustainability) when working in the Richmond community.

- Finally, it was interesting to hear Ian Lai articulate the importance of to valueing immigrant’s knowledge, culture and traditions in order to empower them to make positive change for themselves and their community. This is in line with our preliminary assertions derived from the work of Renzaho & Mellor (2010) that newly landed immigrants are often often plagued by low self-esteem and by attributing value to their knowledge and cultural practices, we can enhance their civic engagement. This, in turn makes people feel more included in society and by extension can make them more food secure.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to draw any broad conclusions from this research. There are numerous limitations to our results including: (1) We had only spoke to two individuals, (2) both interviewees were from very different backgrounds, (3) our methods of data collection and analysis are highly subjective and (4) we did not use a standardized question set because we had to change our questions to suit each interviewee.

Conclusion

From our research, we derived a number of recommendations and conclusions regarding new immigrants’ food security in Richmond. To improve food security, there should be a focus on younger generations through school-based initiatives that teach students the importance and process of sustainable food procurement. These programs will familiarize children with their local food system. Focusing on children will likely also help parents to get more involved in their community. We also suggest volunteering become a largerer part of the school curriculum since it is a gateway to civic engagement and community involvement, as demonstrated through our CBEL project. A third recommendation derived from our own volunteering experiences in the community gardens of Richmond is the incorporation of new gardening programs. Offering programs in the native languages of immigrants (such as Chinese), could act to both increase their community involvement and increase their food security by teaching them how to cultivate their own food.

Although we cannot draw definite conclusions due to the limitations mentioned above, our interviews elucidated some ways that the RFSS could work to improve food security in its community through engaging people. The food security of new immigrants can be improved through initiatives designed to connect people. By establishing a sense of community among immigrants, the RFSS can promote civic engagement and enhance food security.

References

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods and Research 10(2), 141-163.

Erlich, T. (2000). Civic responsibility and higher education. Westport, CT: The American Council on Education and The Oryx Press.

City of Richmond. (2011) Ethnicity hot facts. Richmond, BC. Retrieved from http://www.richmond.ca/__shared/assets/2006_Ethnicity20987.pdf

Goodman, A. (1961). Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 32(1), 148-170. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2237615

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice. New York; London: Routledge

Koc, M. & Welsh J. (2011, November). Food, foodways and immigrant experience. Paper written for the Multiculturalism Program, Department of Canadian

- Heritage at the Canadian Ethnic Studies Association Conference, Halifax, NS.

Monroe, M. C. (2002). Evaluation s friendly voice: The structured open-ended interview. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 1(2), 101-

- 106.doi:10.1080/15330150213993

McCullum, Christine, et al. (2005). Evidence-based strategies to build community food security. Journal of the American Dietetic Association.105.2: 278-283.

Oatey, A. (1999). The strengths and limitations of interviews as a research techniques for studying television viewers. Retrieved from

O'Hara, P., & Neutel, C. I. (2002). Maintaining confidentiality in research data. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 11(1), 75-78.doi:10.1002/pds.680

Renzaho, A. M. N. & Mellor, D. (2010). Food security measurement in cultural pluralism: Missing the point or conceptual misunderstanding?. Nutrition, 26,

- 1-9.doi:10.1016/j.nut.2009.05.001

Richmond Food Security Society. (2014). Mandate. Retrieved from http://www.richmondfoodsecurity.org.

Rojas, A., Black, J., Chapman, G., Lomas, C., Orego, E., Valley, W., & Mansfield, B. (2012). Annual report.

- Retrieved from http://lfs-teg collab.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2013/04/ThinkEatGreen_AnnualReport_FINAL_4Nov2013_WEB-FINAL1.pdf

Sage, C. (2012). Environment and food. Abingdon, Oxon: Routlege.

Singer, J. (2009). Ethnography. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 86, 191-198. doi: 10.1177/107769900908600112

Thomas, D. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27, 237-246.

- doi:10.1177/10982 14005283748

Wilkins, J. L. (2005). Eating right here: Moving from consumer to food citizen. Agriculture and Human Values, 22(3), 269-273.

Appendix

Email Requesting Participation

This is the email we sent to potential participants asking if they would be willing to take part in our study. We attached with this email the consent form and question set (see below).

Dear _______,

My name is Zoë Johnson and I am an undergraduate student in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems at UBC. Myself and a group of my colleagues are currently conducting an ethnographic study in partnership with the Richmond Food Security Society. We are examining how immigrants of Chinese descent in Richmond adapt to western and Canadian forms of civic engagement and how they perceive the connections between civic engagement and food security. We are seeking Chinese Canadians with long-term engagement in their local food system to participate in our study. We would require 20-30 minutes of your time to conduct an on camera interview.

Using the data we collect in these interviews, we hope to construct a narrative that illustrates the ways in which long term Chinese Canadian residents have become involved in their food system. The point of sharing these stories is to start a dialogue aimed at defining and sharing skills of civic engagement with community members who have immigrated to Richmond more recently. The interview footage will be used in a documentary style video recording which will be part of our final report and which we will pass over to the Richmond Food Security Society.

I have attached a document outlining the background for our study which I hope will illuminate a little more what we mean by the "connections between civic engagement and food security." Ultimately, we are just looking to hear your opinions, experiences and stories about the way you interact with your community and your food system. I have also attached the questions we would ask in the interview and a copy of the consent form we would ask you to sign if you decide to participate.

If you are willing to participate in our study, we would love to set up a time to meet with you and learn about your history of civic engagement and involvement with the food system in Richmond. If you have any questions about our research or would like more information about the study or what your participation would entail, please feel free to contact me.

Kind Regards,

Zoë

Interview Questions and Design Process

These Interview questions were designed to guide the conversation of our open ended interviews. The questions we actually asked in each interview varied slightly to suit the participant. At the outset of our interviews, we provided participants with our definitions of food security and civic engagement which are important to understanding our questions. We encouraged interveiwees to answer the questions with stories or anecdotes of their experiences in order to strengthen our narrative. We also urged them to ask for clarification whenever necessary. Finally, participants were informed that they were not obliged to answer any of the questions asked. The were told to pass on any questions that they preferred not to answer.

Definitions:

Food security is defined as “access by all people, at all times, to food that is safe, nutritionally adequate and personally acceptable and which is obtained in a manner that respects human dignity” (Koc & Welsh, 2002, p. 4)

Civic engagement is defined as the effort of an individual or collective group to recognize and address issues of public concern. Civically engaged individuals work to enhance the quality of life in a community, through both political and non-political processes. Part of being civically engaged means recognizing oneself as part of a larger social fabric and therefore accepting at least partial responsibility for the social problems you observe (Erlich, 2000).

Introductory and Preliminary Questions:

What is your name?

What is your age?

What region of China are you from?

What year did you emigrate (leave China)?

What year did you immigration to…

- → Canada?

- → B.C.?

- → Richmond?

What level of education do you have?

What field(s) did you study?

Number of years of civic engagement?

- → In China.

- → in Canada.

- → in Richmond.

What’s your current job title?

What other jobs have you had related to food/food systems?

What is your current annual income bracket?

a. Under 10,000 b. 10,000 – 25,000 c. 25,000 – 35,000 d. 35,000 - 45,000

e. 45,000 – 55,000 f. 75,000 – 100,000 g. over 100,000

Study Questions:

How would you identify yourself: do you see yourself as predominantly Chinese, predominantly Canadian or somewhere in between?

What challenges or advantages do you feel are caused by of this perceived identity?

Were you civically engaged (in the food system or otherwise) in China?

- → please describe.

What was the culture of civic engagement in China? Was being civically engaged the norm or was it unusual?

How did your civic engagement change the way people in your community perceived you? How did it change the way you perceived yourself?

After immigrating, how have you been civically engaged (in the food system or otherwise) in Canada?

- → please describe.

How long after coming to Canada did you become engaged?

How did civic engagement change your relationship with your new community?

- → Do you have any stories about how it changed the way you related to your new home (or specifically the culture of food in your new home)?

What do you think the about the culture of civic engagement in Canada?

How did your civic engagement in Canada change the way people in the community (immigrant community and/or community at large) perceived you? How did it change the way you perceived yourself in Canada?

Do you think the culture of civic engagement among immigrant communities in Richmond is different that in Richmond as a whole?

- → How?

How do you think civic engagement has changed in the last 10 years?

- → How do you think it has changed among immigrant communities in Richmond?

- → How do you think it has changed in Richmond as a whole? Beyond?

What challenges did you face during the transitional period after immigrating to Canada?

- → What challenges did you experience in terms of food security?

- → What challenges did you face in terms of civic engagement?

- → How did you overcome these challenges?

Do you have any stories you would be willing to share about how your relationship with food changed when you moved to Canada?

- → How has the way you eat (food choice or preferences) changed? Was this by choice or necessity?

- → How have your values around food or food cultures changed or to what extent have they stayed the same?

- → If they’ve changed, why do you think that this has happened?

- → If they’ve stayed the same, how have you managed to keep these traditions/values alive?

- → How has your perception of healthy eating changed? Is it mainly based on mainstream or traditional values?

How do you think civic engagement and food security are related?

- → How are they related in general?

- → How are they related in immigrant communities in particular?

What changes have you observed in terms of food security in your community in the last ten years?

- → Have the barriers to access to good, appropriate food changed? How?

- → Do you see positive or negative change in the food security of people in your community?

- → If so, why do you think these changes have taken place?

What changes have you observed in terms of civic engagement in your community in the last ten years?

- → Have the factors that influence the way people become engaged changed? How?

How do you think has the relationship between civic engagement and food security changed in the last ten years?

What do you think the future holds for civic engagement in your community?

- → What factors influence the ways people become engaged and how do you think they will change in the future?

How do you think food security will change in your community in the future?

- → If you have see positive change in terms of food security in your community, then given that people are generally more food secure now, do you think people perceive it as a less important issue? How do you think this might change their motivation to become civically engaged?

Interview Transcripts

Interviewee: Ian Lai

Interviewer: Zoë Johnson

Date: 9am, Friday, October 31st, 2014

File Name: MVI_6342

1:44 “I’m born and raised in South Africa. My parents are of Cantonese descent, so I’m first generation South African.

1:56 “[My parents] are from Canton”

2:05 “[We immigrated] in 1979”

2:10 “No, we’ve always been in Vancouver and I travelled around. My base is, I guess, the Lower Mainland”

2:22 Level of education: “I have post-secondary” Field: Criminology and psychology

2:34 “I’ve been involved in the project for 10 years.”

2:52 “My current job title is Program Director for the Richmond Schoolyard Society. I am self-employed, so I have many hats that I put on. So I work for the Schoolyard Society, I work for the Vancouver Food Bank, I work for the David Suzuki Foundation, I’m a part owner of Northwest Culinary, and I work for the City of Richmond as well as the Corporation of Delta.”

3:26 “[My job] is always about food systems, food security and food sovereignty.”

Perceived identity

3:53 “I consider myself Canadian. I don’t have an affinity having been brought up in South Africa and lived at Japan. I just feel very global. When I’m in Canada, I feel Canadian. When I’m travelling, it’s much more patriotic”

Challenges with perceived identity

4:24 “I don’t see any challenges with who I feel that I am.”

The Richmond Schoolyard Society

4:48 “Well obviously the project I’m most excited about is the Richmond Schoolyard Society because I founded it years ago, and it’s based in my hometown, and I feel that I have an investment with all the children that live around.” Richmond Schoolyard Society works with children. We work with them at school or they come to the site here. We teach them about growing food. We teach them about cooking, we teach them about health and nutrition. It all ties in with the bigger issue of food sovereignty and food security. We teach them about seed saving. We teach them about the whole food cycle from food to table back into compost, and they partake in the bigger picture of helping the community. Any food that they do not harvest from the gardens gets donated to an organization in need.

More about the Richmond Schoolyard Society

5:48 “The program is run through schools, it’s part of the school curriculum. We are, I guess, the subject matter experts at this point, and we work with the school for about two years. The teachers learn about the program and after a few years they feel comfortable to run it on their own. So we engage with elementary schools most of the time, not too many high schools.”

6:20 “We started off at this site but a lot of schools are too far away, so if you come to the program here you would have to walk or you have to bike. Again, it’s talking about the carbon footprint, so schools that are further away actually have school gardens on the site. So this is home base, and then we have satellite projects throughout the Richmond Area.”

How do you feel your civic engagement has changed your relationship with the community?

7:10 “The civic engagement piece doesn’t make me feel I’m any more special. I see myself as an educator, just like any elementary school teacher would. You’re inspiring children, you’re motivating them, you’re teaching them something that they probably don’t know or don’t realize. So as an educator I’m just there to facilitate and to lead them on to something that may eventually change their behavior. Maybe change the behavior of what their family does, how they eat, how they see food, and how they feel as an important part of the community.”

What do you think about the culture of civic engagement in Canada?

8:35 “I think civic engagement in Richmond is still new. We have a large immigrant population that does not engage because they have too many stresses in their life. They’re starting to settle down, they come from a culture where there is very little civic engagement. In the area of Richmond, because of the language issues, sometimes it’s difficult for me, as a catalyst that doesn’t speak Cantonese or Mandarin, to engage with a large part of the community.

9:18 “I can engage with the children, but in Richmond I think there is a need, there is an interest [for civic engagement]. It needs to develop and it needs to grow a little bit more”

How do you get volunteers for the Richmond Schoolyard Society

9:39 “We have staff. Our project has staff, we always invite parents who have children in the program to participate. So sometimes parents will join in a class, they’ll listen, they’ll learn, they may help with the children in the garden, they’ll help with cooking. Generally, it’s Canadian parents that do that. Immigrant parents find it hard to communicate, and there’s a hesitation. It’s not a lack of skill, it’s just the language and speed of how to communicate is a lot slower.”

How do you think your civic engagement changed how people in the community perceive you as? How has it changed your position in the community?

10:54 “I think it’s given me insight into how to teach better. It gives me an opportunity to work with different populations. I’m learning all the time. When you work with children that come from different backgrounds depending on what part of Richmond you’re in, you have to have a cultural lens to teach through. I don't see myself as any person that is special. I think being part of civic engagement is about being humble. Parents see me as a teacher. Children see me, and they see me as a teacher. So, you know, I feel no bigger or better than other educators. My role is to get people excited about food and see things from a different perspective.”

Do you think the culture of civic engagement in immigrant populations are different than that of Canadians?

12:22 “I think with a lot of immigrant groups in the city, they work really hard altogether, so they are involved in civic engagement but they do it as ‘the Muslim community, or the Chinese community, or the Taiwanese community’. What we need to try to make happen is to bridge those gaps, so that we’re working multiculturally instead of monoculturally. I think these communities do a lot of work within their own community because it’s comfortable, the language is easily understandable, and the children are involved.

13:00 “I think the challenge is to help those groups extend beyond their comfort zone and to blend a little bit more in because everyone’s doing the same thing, and they all have the same goals. It’s just when you see it from a Canadian lens, they seem to be very isolated or almost like a silo. They do their own kind of work, and I think it would be nice when, and it is nice when we are in the school, that we have different cultural groups working together in the garden.”

How do you think civic engagement changed throughout your time in Richmond?

13:58 “People get involved in our projects through experience, first-hand experience. If we’re in the school, parents are seeing what’s happening or even if they’re not involved at the school, the children bring homework that is related to the topic we’ve done that day. Parents sometimes read it, they’ll have an interest and then they’ll come in and see what’s happening. So how do you promote this? You know, it’s feet on the ground. It’s teaching, it’s opening up conversations. I’ve done work at the public library, where you have a lot of different groups coming in throughout the day, and having food demonstrations and have children involved”

14:39 “When parents are involved firsthand, they realize that they are an asset regardless of how much English they speak. Gardening and food is cross-cultural, so there’s a commonality when we’re cooking and when we’re out in the garden.”

What challenges did you face as a new immigrant to Canada?

15:31 “As an immigrant child, the biggest challenge was finding my identity within Canadian culture. When you come to Canada, you know… when I came to Canada, I wore clothes that were different. I had no backpack, I had a different kind of school bag. My accent was different. So right away, you’re on defense. You kind of hide yourself a little bit, and it’s only when you start to find something that other students see that you’re at the same level, and I did it through sports, that ‘oh, he’s one of us’. So I think with a lot of immigrant children, they need to feel that they’re recognized for their culture. If they’re kept aside or they are on their own it’s hard for them to integrate. I think with schools there needs to be teachers, educators, and staff that are more aware of all the different cultural groups in their school, what their identities are and how to make them feel comfortable and recognized from day one, and value their culture, so they are able to have a little bit more confidence and self-esteem when they start school.” How did your relationship with food change since coming to Canada?

17:27 “In South Africa, my parents had a fish and chips shop. They were involved in food, so I grew up with food. But coming to Canada it was different. The way we shop was different: the supermarkets and aisles and aisles of different things. My brother worked in the restaurant business, and I had a job in a restaurant right when I came to Canada, so I was involved with food very early on. It gave me an opportunity to see Western food at its best, he worked in a restaurant that was very fancy, they wore tuxedos. They cook in front of the table. As a sixteen-year-old coming to Canada, seeing that, my brother was like a hero. I got to see all these fancy foods. So my involvement with food at a high price end level started very early on in life.”

18:29 “That has changed dramatically since I’ve started to work in food systems and food security, where I value the 95% of the population that generally cannot afford to pay $200-$300 for a meal. I have changed the way I cook, I’ve changed the way I teach food. I’ve changed the demographics of the people I work with because I feel that the 95% of people don’t have as much education about food and food systems, and my role as an educator is to get them excited and to understand the bigger picture.”

File Name: MVI_6343.MOV

How does changing the community’s relationship/knowledge with food affects their food security?

0:11 “I think the first step is to have old residents involved in civic engagement. It doesn’t have to be food. Once they’re involved in civic engagement it allows us the opportunity to draw from those champions and talk about food. Food security is such an eseteric(?) term that people don’t understand it. In order for us to make it understandable, there needs to be examples to show people, that growing food, that buying locally, that making food choices not only your food dollars but some food dollars to support local farmers and markets, does help the economy and build strength within the community”

Changes seen in food security in Richmond through the years.

1:38 “I think residents in Richmond are more aware of food over the past ten years. Food knowledge has increased. I think the Ministry of Agriculture and schools and the whole eating right and the Action BC programs have generated interest within the school population, and having fresh snacks available has changed a lot of the ideas of food. The children I work with are very interested in how their food grows and what part they play in the bigger picture. In Richmond, there are a lot of different markets that are accessible to people.”

2:15 “Pricing is still reasonable. When we talk about farmers’ markets, when we talk about organic food that’s a different layer that is still unaffordable for a lot of people. Personally, my family doesn’t eat organic all the time. We choose where to put our dollars into organics. So for me as an educator, my biggest challenge or my biggest success is when people move off of canned foods, salty foods, packaged foods. For me, it doesn’t really matter if the vegetables are coming from China or Mexico. They’re still fresh, they’re the better of the two options, the lesser of two evils compared to pre-processed food. So I think if we have a group of people that understand that fresh food is better, that it does take time to prepare food, it does cost less but costing less has to balance with the amount of time parents have for shopping, for cooking, that in the long run it is a benefit.

Views on the future of civic engagement with food security issues

4:05 “I’m always hopeful that what we’re doing does make an impact on people. I can see it in the groups I work with, when I’m working at the food bank or when I’m working with the community, I see people appreciating food a little bit more. There’s a lot more respect for the people that grow food and there’s a lot more connections and ‘aha’ moments when you talk about food, where it comes from, where it’s travelled. When we tie in ethnic foods in a lesson, you can see children’s eyes light up because you’ve recognized that their cultural food is important in the big perspective of Richmond.”

Interviewee: Karen Dar Woon

Interviewer: Zoë Johnson

Date: 2pm, Friday, November 14th 2014

File Name: Clip #11.mov

1:38 “My name is Karen Dar Woon. I am 56, I just had my birthday.”

1:48 “To the best of my knowledge, my family is from the Southern region of China, formerly known as Canton province.”

Year that her family left China

2:05 “Pre-1925. I believe my father’s family lived in Calgary, Alberta, and my mother’s family may have been the children in Canada. I know both my parents were born in Canada.”

2:34 “I have a couple of different courses of completion at BCIT. One in physical metallurgy and engineering technology, and another in business development. So it was the self-employment program. And I’m also a culinary professional.

3:06 “I didn’t go to a professional culinary institute but I did take several amateur classes through the professional culinary institute, the Northwest Culinary. Chef Tony, who was the principal, I believe his family is from the Pia Monte region of Italy, which is one of the regions I visited, so it was really fun.

3:40 “I have a business as a personal chef, so I have my own business operator. Within the realm of a personal chef, I provide individual and group classes within the community and through private enterprises and individuals. I work with the community to provide self-catering for organizations and event planning and event catering

4:22 “I have been a personal chef only for about ten years, and while I was developing my business I worked in restaurants and catering. I volunteered for many, many years before that in a church women’s group, and we did catering for church events and for some other events as well

How long have you been civically engaged?

4:51 “Our family have always been focused on volunteerism and being part of our community” Current income bracket

5:04 “Oh very low. I am a self-employed person married to a retired person, so… Probably not at poverty level because we are only a family of two, but it’s not high.”

How would you identify yourself? How do you relate to your Chinese heritage?

5:35 “Oh that’s a good question. Well in a census form, I identify myself as Chinese-Canadian… third generation.”

What challenges/advantages do you think you have because of your heritage?

6:10 I think because my parents very… my parents wanted to preserve their ethnic heritage and our cultural heritage, so we really have a strong connection with food, just as a family. So family events always have something to do with food, or there’s always food at family events, and it seems they’re really well integrated to celebration and milestone and ritual and tradition, all has some kind of food context as well as a social context. It’s almost so integrated that you can’t tell which is which… It’s a Chinese-y thing”

How have you been civically engaged in Canada?

7:08 “Church women’s group… I volunteer with different organizations, Coastal Jazz and Blues, which puts on the Jazz Music Festival, the Folk Music Society, Girl Guides many, many years ago. I’ve always been involved in something at my children’s school, for example. My children are also keen to be volunteers. They find opportunities in their community to be engaged. Right now, I was previously on the board of the Sharing Farm, so that’s a very prominent organization in Richmond. That is directly related to the food system. [I have] always been somehow connected to groups that were preparing food or preserving used to be used later, whether it’s within our own community of a club that I was in or the church that I was in, or if it’s part of the broader community. I would say often directly or indirectly, and without thinking that it’s being part of the food system, but more about being part of the community

Do you think your family’s civic engagement is part of the tradition in China? Does the civic engagement of your family have something to do with your Chinese heritage?

8:57 “I don’t believe it does, really. I think it has more to do with being Canadians and having been raised in the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s. Because our population was lower, and the population densities were lower in Western Canada, there was more opportunity for people to meet their neighbors and to spend time building either built environment or social construct within our communities.”

What do you think about the culture of civic engagement in Canada?

9:51 “I always thought that volunteerism, as a way of being civically engaged… I’ve always thought that volunteerism is particularly “Canadianism”. It’s kind of peculiar. There are a lot of people I know from other countries, Western Europe, U.S., South America, and there is not the same degree of volunteerism in other countries as there have been typically in Canada in the last 50 years.

10:31 “I think that changes now because we have a more mobile workforce, also a more… higher population density and higher degree of immigration

How do you think your civic engagement changes the way people in the community perceives you? How does it change your perception of yourself?

11:03 “I would like to think the degree to which I’m engaged in the community allows people to think of me in a very positive way, rather than in a negative way… I think, or hope, that because of the kinds of projects that I get involved in, usually around the food system, that it sort of helps to build my personal brand as well. I mean, I work in food, and it would be… I think that all food professionals really have a responsibility to find out what’s going on in their food system. As a profession, I think we also have a responsibility to build our local food system and to build connections and help others to build connections to their food systems.”

How do you think the culture of civic engagement in the communities change since the time that you’ve been involved in the food system?

12:25 “Part of what I think has changed in the last two generations is that we are… some people are more likely and some people are less likely to identify with their ethnic heritage group. So for example, 45 years ago, we might have had service clubs like Lions and Elks and Rotary… I’m not sure what some of the other ones are, and those groups, those clubs might have had chapters that were specific ethnic groups. I know that, for example, the Chinese community had Chinatown branch of the Lions club, for example. Those communities tend to be quite tightly-knit, maybe? Or they have a lot of self-identity. I’m not sure whether that happens more now or to a lesser degree, it’s kind of hard to say. I know that my observation has been that some ethnic groups work within their own communities rather than working with the broader community.

13:54 “In the Sharing Farm, there have been within the Sharing Farm community, [which is] sort of the broader community, there have been a couple of smaller teams that are engaged in the farm, that are sort of their own little group of their own special language group. I don’t know how else to describe it. Does that make any sense? So within the broader context,there are little sub-communities which I think is very cool, actually. It really provides this vehicle for smaller sub-communities to get to know each other as well.”

About the Sharing Farm

14:52 “The Sharing Farm is… how can I best describe this? The Sharing Farm Society began as a group of people interested in what was going on in the Richmond food system, and recognizing that farmers and gardeners had extra food; and that food is, you know, this is only 15 years ago so it’s not a generation or anything. At the time it seemed that food was being produced and there was nowhere for it to go. So the founders of the Sharing Farm Society came to an arrangement, I think, with the Richmond Food Bank, that volunteers would collect extra food, so “gleaning”, and that the food can be distributed through the Food Bank. Over the years this sort of developed into a plan to have gardens of our own and then a farm.

16:07 “In its current state, the Sharing Farm is 4 acres of planted land that belongs to the City of Richmond, and it’s located in Terra Nova Rural Park. It’s just a great space that has an agricultural heritage, because the space originally was [for] agriculture, and Terra Nova Rural Park was.. in bit of a civic controversy. It was purchased back from the developer in the late 1980s, and it was kind of an exciting time: there was all this land in the northwest corner of Richmond and the developers have purchased the land from the individual landholders. It began the civic movement, a really grassroots movement, to preserve the farmland. We had a referendum to incur a huge amount of debt, it was millions of dollars, which was a lot of money in 1987, or ‘85. I’m trying to remember now what year that was. Anyways, we had a referendum, we were citizens of Richmond, I was living there at the time, decided that we really wanted our park. And so the city bought the land and the council that was sitting at the time was no longer, and we have this beautiful park there. Part of it is returned to its agricultural roots.”

18:03 “If you have the chance to go at different times of the year and walk around the park, as well as the farm site. It’s a very, very interesting space. It’s the home of 5 different organizations.

What are the food security challenges your community faces?

20:07 “When I think about our ethnic community, some of the challenges that… things have probably changed through the years. There’s a lot more access now than there was previously. Certainly at the early end of the 20th century, a lot of food products might not have been available in the kind of supermarket context that we have now. It would have been very uncommon for a local supermarket to have any kind of Chinese food ingredient other than maybe soy sauce, or there was one brand of Chinese food that you can buy in the 1960s. Our family lived in the suburbs, and we would go into Chinatown to go shopping once every week or two.

21:11 “The irony of all that is that the market gardens in South Burnaby and in North Richmond were predominantly grown by Chinese immigrants. Chinese people were growing all these foodstuffs, and yet they’re pretty much only distributed in small ethnic grocery stores, not in the supermarkets. I think that distribution has always been an issue. It doesn’t matter where you are, how rich your neighborhood is or any of that. I think distribution is the big deal. Through the way that transportation works right now, I mean in the 21st century, we can fly food from anywhere to anywhere. Sadly, there is fresh lamb being flown from Australia more than once a week to Vancouver. Doesn’t that seem crazy to you? It just seems crazy to me that we would want or need to transport food so far. I just don’t understand that. I mean, just ordinary food, milk, eggs, meat. I think it’s kind of exciting that we can get this exotic citrus occasionally. I’m sometimes encouraged and sometimes I’m wondering ‘Who thought this was a great idea?’ When we have things like pomelo- it’s a cross between a grapefruit and a tangerine- in our family it was traditionally only… we only had it around Chinese New Year- so January, February, March- sometime in there, because that’s the typical growing season for citrus, because that’s when citrus ripens- in the winter. But now you can get it year-round. I don’t know where it comes from…

23:42 “Well I have a deck garden. It’s about a hundred square feet. So we have things in pots- lemon, lime, rosemary, two olive trees, I have oregano that grow year-round and thyme that grows year-round. It’s really nice. I love it. It’s part of the reason we chose to live in this particular building; it’s because of the aspect of the balcony.

How is your relationship to food different from your parents’?

24:58 “I would think that the predominant difference in my relationship or my generation’s relationship with my parent’s generation’s relationship to food is just in our broader understanding of what tastes good or what constitutes a meal. Frankly, my dad would have considered that spaghetti with [] sauce is not a meal. It doesn’t have all the components that he sees as being a meal, whereas I would consider it a meal but my Italian cousin would think that it’s a snack… I think it depends on… a lot depends on what we’re accustomed to, right? And whether that’s ethnic related or not, there are probably a lot of non-Chinese, like Caucasian, non-Chinese families that also wouldn’t consider the spaghetti [] to be a meal. It could be a generational thing. I think actually it’s a generational thing, because my parents didn’t travel as much or have a much exposure to outside influences as we do. There wasn’t that much TV, I don’t think we had a TV until I was 4… and then my kids have travelled much more extensively than my parents ever had, and I thought my parents travelled a lot. My kids have been all over the world.”

How do you think civic engagement and food security are related?

27:20 “Actually learning about food through working with food is, I think, one of the best ways to improve our knowledge about food and food systems. The more I work with kids, for example, who are learning how to grow their own fruits and vegetables and flowers, the more likely these kids are to recognize those fruits and vegetables in the store and then probably to eat them, especially if they have grown them themselves. They’re more likely to eat it or at least to try it. My nephew loves to grow kale but he thinks it’s terrible. Anyways, we put it in his smoothie. The things is his favorite smoothie is the bright, green one, so he doesn’t want to eat kale by itself but when you put it with some grapes and cucumber, he’s good to go. So he is learning how to grow kale and cucumbers, and he’s learning that grapes have a hard time growing in his yard. His neighbors are Italian. They have grapes…”

28:30 “Even if we look at that very small example, that little micro-community of my nephew’s home and his street where he lives, they got quite a lot of diversity, like cultural background diversity, and they have connected with their neighbors specifically around food. Because the gardens are growing in the front yards and the backyards. The adults are admiring each others’ gardens, and the older adults- on these streets, the older adults are the ones with the most beautiful gardens- they’re really happy to have the opportunity to share the bounty of their garden with some of their younger neighbors, whether they’re the younger adults or the children or whatever. And so when we look at that as kind of this example of how food can be a really great vehicle in connecting people. At the same time, the kids are learning about how the food grows, and the young adults are learning about the food varieties of certain vegetables and fruits. How many people know that zucchini can grow in this kind of trumpet shape right?

File Name: Clip #12.mov

00:01 “There are special Chinese vegetables too that are quite well-adapted to our climate here. There are these strange melons that I don’t like, I don’t like the taste of them so I don’t grow them. We used to call them ‘mice’ because (it’s called a bittermelon) they are eggplant shape with a long tail on the end of it. So it looks like a mouse. They grow really well here. Chinese gardeners grow them, and we grow other kinds of some interesting greens that maybe English gardeners or French gardeners don’t. People who like arugula might probably like this other kind of choy my grandma used to grow. They wouldn’t have known each other then, because their communities are a little bit more segregated. I think that now, there is more mixing, which is great. I think that growing food together, volunteering together in hunger agencies or around poverty response, or even children’s celebrations and things that have food as part of their… maybe not the focus, but part of the event- that’s a really easy way for people to connect with each other and find other ways to connect and work in their communities

What do you see for the future of food security and civic engagement?

2:28 “I’m remaining hopeful. I remain hopeful and at the same time I’m frustrated about what I observe to be the huge distribution problem that we have worldwide. I’m a little frustrated in how small a speck I am in that food system, and I’m not really sure at this point how to work to enact change in that side of things.At the more specifically local level… I mean, right now I live in the CIty of Vancouver, [but] I do a lot of my work in Richmond. That’s where I’m working most in the area of hunger relief and community food because I’m a chef at Gilmore Park Church. We have a community meal every week. Every week, except for December, we serve dinner, anybody can come regardless of social situation or regardless of means, the building is accessible. We’re participating in the food system by being a place where food is available- where healthy food is available. Sometimes we act as a distribution, or a redistribution hub because when I’m sourcing the food, I am able to find off-market produce, like the slightly-scarred, not very beautiful stuff, which are still nutritionally sound and delicious. Delicious is important, right? People who maybe don’t have access to a car or very good public transportation don’t have access to some of the shops that would have off-market produce.

4:56 “In terms of what I see as the future or in the future, I’m hoping that as individuals, civic constituents and family groupings and ethnic communities that we keep working towards wasting less food, eating the food that we actually grow, growing the food we eat- that’s the thing right? We can go wherever what’s being used for making biofuels these days, but it’s taking out land and resources that maybe we can be using to produce actual food, instead of food for cars. Let’s feed people. Or if we’re going to use that to make food for cars, then let’s put some food in the cars while we’re going somewhere and get it where it needs to go. It pains me greatly to drive through a farming community and see piles and piles and piles of rotten squash. I think that’s very sad. Sometimes the reason why there are piles of rotten squash is because our food system is so broken that our farmers can’t pay someone to come and pick the squash, so the squash remains unpicked and rots on the vine. I think that’s really sad, but I also think the people who grow our food should not be living in poverty. I think our system is so broken. If each of us starts to take steps towards making the system unbroken or less broken, I think eventually the system can be fixed. Hopefully there’s someone who has a political will to push that along”