Course:KIN355/2020 Projects/Extensions in Space

Extensions in Space

Defining the Concept and Its Importance

Extensions in space are the most complex movement concept associated with spatial awareness. Other spatial awareness concepts include understanding general space, self space, different directions, levels, and pathways[1]. Extensions in space refer to the size of the movement that is being performed in a given space[2]. The body can only extend far enough to a certain point where it can reach and carry out a specific movement[2]. Some extensions are stronger and more reliable while other extensions will lack power or accuracy. As mentioned in Dr. Bredin's Kinesiology 355 lecture "Movement Experiences for Young Children”, extensions are the last spatial awareness concept to be developed by children. Before this concept is developed, a certain level of skill is needed before it is classified as a child motor movement[2]. Prior to the development of extensions, a child must demonstrate an understanding of the travel of the body through different air pathways, directional based movements, and different levels (high, middle, and low) a movement can be performed[2]. After these skills have been acquired, children then must learn how and when to use larger extensions versus smaller extensions and far extensions versus close extensions as this will correlate to better movement performance. A child will experience this movement development as soon as the other basic movement concepts preceded by extensions have emerged. These preceding concepts are essential as they provide the foundation for children to be able to proceed to learning the more advanced concept of extensions.

Spatial awareness is an important aspect of childhood movement experiences, especially as children get older and more advanced techniques such as extensions of the body begin to develop. It can be hypothesized that learning the motor concept at a younger age will allow for better development in the sport of choice and a physical movement later on. For example, when thinking of the sport tennis, a player can have a statistical advantage if they provide more extension in their rear when practicing a forward swing[3]. When a better extension is provided in one area of an athlete’s game, it will result in a better performance which depends on the development of these basic movement skills throughout childhood growth. As you get older, minor changes in these spatial awareness skills, such as a larger elbow angle in a tennis stroke will result in better tennis stroke performance[3]. Although these examples are for more advanced extension skills, it all correlates to children benefiting from the development of spatial awareness of body extension early on. If children lack the development of extensions, it can be detrimental to learning new physical movements and other basic mechanics of the body.

Educators, coaches, and parents need to understand the basic mechanics of spatial awareness and the importance of child development. As suggested in Piaget's theory of cognitive constructivism, children develop at different rates and cannot be given information and immediately understand it[4]. Instead, humans will construct their knowledge and better yet, will learn movements naturally and over time like extensions[4]. As extensions are developed slowly throughout a child's development period, different rates of development should be taken into consideration.

Role in Childhood Development and Contemporary Considerations

The concept of extensions in spatial awareness is important in childhood development for several reasons. As a child grows, they get stronger, bigger, and begin learning new skills. Without the development of basic fundamental motor skills and some concepts of body awareness, extensions cannot be learnt. Fundamental motor skills such as non-locomotory skills, locomotor skills and manipulative skills are all imperative to the development of a child. Some of the fundamental motor skills include walking, running, pulling, balancing, and throwing. It was found through a meta-analysis test that the development of spatial awareness skills is influenced by locomotor experiences[5]. Therefore, it emphasizes the importance of developing fundamental motor skills at a young age.

If the manipulative skill of throwing, propelling an object in the air using force is not developed, it is impossible to learn the extensions of throwing. Extensions involve the size of the movement relative to the space given. Hence, the manipulative skill of throwing may not develop any extensions because the overall skill has not been learnt. Think of the sport baseball. Some of the basic fundamental movements in baseball include running, throwing, and catching. If an individual does not know how to throw a ball it is often because the individual cannot play the sport which means they cannot learn extensions in the given space for that motor skill. Throwing the ball with better velocity requires a leg lift that is large with significant rotation[6]. For improved skills, athletes will learn to throw the ball with a higher lifted leg in the air, however, it is impossible to learn this if the basic skill has not been developed.

Another factor that teachers and coaches should be aware of is the development of body awareness. Body awareness is a movement concept like spatial awareness. These movement concepts are all frameworks to effectively help students become more skilful and knowledgeable about a given movement. As mentioned in the Ontario Curriculum Manual for grades 1 to 8 of Health and Physical Education, body awareness is associated with the part of the body that produces the movement and understanding why those parts are moving. These movements could include wide, narrow, and stretched out actions[1]. Children must have an understanding of where the body parts are and the position that the body is in otherwise many other movement concepts cannot be developed, especially the movement concept of extensions in space. Without understanding where your hand is in a given air pathway, the size of the movement in a given space cannot be learnt. It is important at a young age that children develop basic fundamental motor skills so that other movement concepts can be developed at a later age. If a child does not learn the fundamental motor skills, it will be impactful and may hinder their development.

Educators and coaches for the younger ages should focus on teaching children fundamental motor movements and generating new skills and concepts they have not developed. To do so, games such as throwing a ball through a specific target is a good start before advancing to more complex spatial movements. Once mastered, challenges and games can be adapted for the child that will benefit them later on. For example, a child can throw a ball through a target, however, only given a confined space which will benefit the child's future understanding of spatial awareness. Throwing a ball through a target is specifically for the manipulative skill of throwing and does not involve other skills. It is why physical activity and activities like such are important for all skills, not only a few. From there, a child may learn to throw the ball with more power in a given space and can look into throwing larger motions versus smaller motions.

Educators should be aware of learning growth occurring at different times. Especially for more advanced movement concepts, children will learn new advanced motor concepts like extensions at any point after they have achieved success with their fundamental motor skills. In order to create a competent movement, a movement skill and a concept must be incorporated with a movement strategy[7]. A skill such as stability or any locomotion skill will be combined with a concept like spatial awareness. From there, a task such as the demonstration of a kicking motion is considered the movement strategy. To create this movement strategy, both the movement skill and the movement concept must be developed. It may help in the explanation of the importance of extensions relative to spatial awareness in any given movement skill.

Practical Applications

Activity 1: Escape the Jungle

Purpose: The goal of this obstacle course is to develop or enhance a child’s ability to perform extensions of the body and refine their spatial awareness skills. This game also requires the child to have an understanding of body awareness to produce the desired movement required. Stage 1 mainly focuses on extensions in the legs. A child may also extend their arms to help maintain their balance and use their arms to provide more momentum and force. By spacing out the placement of “rocks” at varying distances, a child can practice extending their limbs in a controlled manner to land into the target. Stage 2 works on extensions of the entire body. A child will be able to learn how to manipulate their body and when the use of close or far extensions is appropriate to be able to move through their environment while avoiding the “vines”. Stage 2 affords the opportunity for a child to increase their awareness of their surroundings, extend their body in a controlled manner, and maintain balance to prevent themselves from touching the “vines”. Stage 3 mainly focuses on the development of extensions in the arms. By spacing out the placement of the “tree branches” at varying heights against a wall or door, a child can practice extending their arms from the center of their body to be able to reach and carry out the appropriate movement to grab objects in their surroundings. A child may also extend their toes into a tip toed position or extend their legs to jump and propel their body upwards to be able to reach the “tree branches”. Stage 3 could expose a child to developing similar movement skills seen in volleyball (e.g. tip), baseball (e.g. extending the arm to catch or throw a ball), tennis and badminton (e.g. extending the arm when carrying out a stroke or serve).

Target age: 6+ years of age.

By the age of 6, most children are able to run, jump, skip with ease, and usually have good balance (Healthwise, 2019). By the age of 2, children have acquired the ability to reach, grasp, and release objects (Gerber et al., 2010). Thus, this obstacle course should be developmentally appropriate for children from ages 6 and up.

Apparatus/equipment needed and environmental space/set-up:

Environmental space:

- Hallway, room with a clear path in the middle, or in an open gym. If you do not have enough open space in one room, you can have each stage of the obstacle course set up in separate rooms.

Equipment:

- Baseball bases, hoops, or cut out your own circle or square shaped markers out of paper to act as “rocks” in stage 1 of the obstacle course

- String, tape, or streamers to act as the “vines” used in stage 2 of the obstacle course

- 5 straws, pens, pencils, or chopsticks for each child, to act as “tree branches” in stage 3 of the obstacle course

- Tape

Instructions:

- In a hallway, room with a clear path in the middle, or in an open gym set up the obstacle course (see Figure 1. for reference).

- Place your “rocks” on the floor at varying distances from close to far for stage 1 of the obstacle course

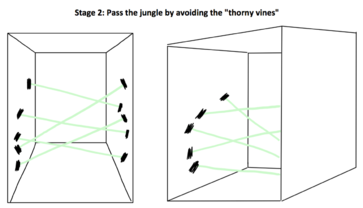

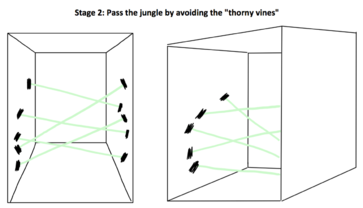

- With your “vines” tape each end against the side wall for stage 2 of the obstacle course. The number of "vines" used will depend on how big the space is (e.g. if in a gymnasium you may use up to 20 vines, if in a hallway you may use 10 vines) and how challenging you want this stage to be. Keep in mind to leave enough space so the child can actually fit through the gaps/holes created by the “vines” (see Figure 2. for reference).

Figure 2. Set up for Stage 2 of the Escape the Jungle obstacle course - Tape 5 “branches” onto the wall or against a door, have them placed at varying distances from close to far. Keep in mind to not tape the “branches” too far/high up that it goes beyond a child's ability to reach when they are on their tippy toes or within jump reach. (If played in a gymnasium at school, you can place children of similar height into groups of 10-12 and have them complete the obstacle course at the same time so that the “branches” that are placed further up accommodate for their height and make sure there is enough “branches” against the wall or door for each child to collect 5).

- Complete the obstacle course.

- Stage 1: pass the jungle by only stepping on the “rocks” to avoid falling onto the "thorny vines" on the ground. If the child misses their landing onto a "rock", they must start at the beginning of stage 1 again.

- Stage 2: pass the jungle by moving through the “thorny vines”, do not touch the “thorny vines” or you will get hurt. If the child touches a "vine", they must go back to the start of stage 2 again.

- Stage 3: collect 5 "tree branches" from the “tree” (i.e. the wall or door)

- The objective of the game is to pass all 3 stages so that the child can “escape the jungle”.

Modifications:

-If the child lacks control and ability in carrying out the far extensions, you can increase the distance of the placement between each of the “rocks” in stage 1 and “branches” in stage 3 from the child so that they can work on developing their ability to perform far extensions.

-If the child lacks control and ability in carrying out the close extensions, you can decrease the distance of the placement between each of the “rocks” in stage 1 and “branches” in stage 3 from the child so that they can work on developing their ability to perform close extensions.

-Increase the difficulty of stage 2 by placing more “vines” to make the vine maze more intricate. By doing so, the child must acquire greater spatial awareness and control of extensions of their body to pass this stage.

-Increase the number of “branches” the child must collect in stage 3 (e.g. 10 instead of 5)

-Can make the obstacle course more challenging by having the child return to the start of the obstacle course if they fall (e.g. if the child touches a “vine” in stage 2, they must return to the start of stage 1 instead of returning to the start of stage 2).

Activity 2: Target Dance

Purpose: The purpose of this game is to work on the child’s ability to extend their arms and legs from the center of their body to reach the correct targets. This game can enhance a child’s attention to their surroundings as they must carefully identify where the correct target is in their environment and then extend the correct limb to reach the targets. This game also requires the child to have an understanding of body awareness, especially body concept to be able to identify their right foot, left foot, right hand, and left hand. By incorporating the use of music, this is intended to help encourage the child to perform more forceful and fluid movement trajectories to help them extend their limbs in a controlled manner. Children may naturally match their movement to the rhythm of the music which can lead to better movement performance. This game is a good starting point for children to develop extensions of the body. It affords the child the opportunity to practice aiming and reaching towards targets. These skills will be useful once children begin to engage in sports such as baseball, tennis, and badminton, where having a solid foundation of extensions of the body is crucial. The game mimics motions similar to throwing a ball or carrying out a tennis or badminton stroke to aim towards your target. It also mimics the action of pivoting which is a useful skill in basketball.

Target age: 6-7+ years of age.

By the age of 6-7, most children can identify their right foot, left foot, right hand, and left hand (Healthwise, 2019). Children between the age of 6-7 and up should be able to identify colours, especially, primary colours. At the age of 6, children usually have good balance (Healthwise, 2019). Thus, this game should be developmentally appropriate for children from ages 6-7 and up.

Apparatus/equipment needed and environmental space/set-up:

Environmental space:

Equipment:

- Coloured targets (use different coloured construction paper to cut out 10 inch circles or a circle large enough to fit a child’s foot and hand out of each coloured paper)

- Tape

- Target cards (create a set of target cards using blank/unruled index cards or paper that specify the side of each limb (e.g. left or right), which limb (e.g. foot or hand) and the colour of the target (e.g. red, blue, etc)). For each coloured target there should be a target card that says right foot and the colour of the target, left foot and the colour of the target, right hand and the colour of the target, and left hand and the colour of the target. (see Figure 3. for a reference on how to create the cards).

- Music

- A caller to read out the target cards

Instructions:

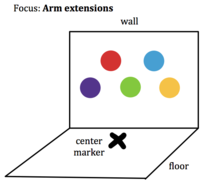

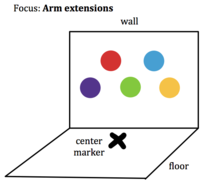

- Tape the targets to the floor, create an x-shaped center marker in the center of all targets using tape (see Figure 4. for reference on how to set up the game) and prepare a deck of target cards (see Figure 3. for reference on how to create the cards).

- The player will start by standing on the center marker

- The caller will turn on the music to simulate a dance game

- The game begins once the caller chooses a card from the shuffled deck of target cards and reads it out loud for the player

- The player then must carry out the correct movement that corresponds to the target card. (For example: if the card is “right hand blue”, the child must keep their feet and left hand within the center marker space and only extend their right hand to reach the blue target on the floor. It is up to the player how they want to carry out this movement as long as they only aim to reach the target with the limb presented on the target card (e.g. they can bend their legs down and then extend their arm, they can bend forward to reach the target with their hand, etc).

- The player can only move the limb that corresponds to the target card chosen towards the target while keeping other limbs within the center marker space.

- Once the player successfully completes the correct movement. The child can reset their body to stand back into the center marker.

Figure 5. Target Dance: wall set up - The caller will then immediately read out the next chosen target card once the player completes the previous movement correctly. (The caller should have the next card chosen and ready as the player is carrying out the current target to keep the game moving smoothly without long pauses or breaks between each target)

- The game ends after the player successfully completes a sequence of 20 target cards correctly or once the song ends.

Modifications:

-To increase the difficulty of arm extensions. Can modify the set up of the game, by placing the targets on the wall instead of the floor so that the child must reach and extend their arms further to reach the target. If allowed by a parent/guardian/teacher/instructor and if the child is flexible enough, the child can also extend their legs to aim their foot to reach the targets on the wall. If not, remove the targets cards that say foot from the deck of target cards, thus this modification will only work on extensions of the arm (see Figure 5. for reference on how to set up this modification of the game)

-To increase the difficulty of the game, have a set of targets on the floor and wall, this will require the child to increase their spatial awareness because now they must attend to 2 surfaces - the wall and the floor, instead of just one surface. (see Figure 6. for reference on how to set up this modification of the game). Target cards for this modification now must also specify the location of the target (e.g. wall or floor), this modification will double the set of cards you had originally as there are 2 surfaces for the location of the targets (see Figure 7. on how to create the cards for this modification). Once again, if allowed by a parent/guardian/teacher/instructor and if the child is flexible enough, the child can also extend their legs to aim their foot to reach the targets on the wall. If not, remove the targets cards that say foot matched with wall from the deck of target cards, by doing so this modification will only allow for extensions of the arm on the wall but the child will still have the opportunity to work on leg and arm extensions on the floor. (Example for the flow of the game in this modification: caller will say the target card “right hand blue on the wall”, once the child successfully completes that the next target card the caller says is “left hand red on the floor”.)

-Increase the number of target cards the child must successfully complete in sequence to end the game (e.g. 25 cards instead of 20 cards).

-Can make the game more challenging by having the child complete a certain number of target cards successfully in sequence within a time limit (e.g. successfully complete 20 target cards within 1 minute).

-Increase the distance of the targets if you want to improve on far extensions, or decrease the distance of the targets if you want to improve on close extensions.

-If multiple players are playing, to make the game more competitive you can eliminate the player that completes the target card the slowest for each round, the player that is the last one standing will be the winner.

Summary

Insert video vignette...as per Section 4 requirements.

References

Insert references (APA), in alphabetical order.

Section 1 & 2:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Ontario Curriculum. (2019). Health and Physical Education. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/2019-health-physical-education-grades-1to8.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Bredin, S. (2020). Module 4: Developing Fundamental Movements:4.2 An Overview of the Fundamentals of Human Movements, Kin 355 – Movement Experiences for Young Children, School of Kinesiology, University of British Columbia

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Reid, M., Elliot, B., & Crespo, M. (2013). Mechanics and learning practices associated with the tennis forehand: A review.Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 12(1), 225-231. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3761830/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Powell, K.C., & Kalina, C.J. (2009) Cognitive and social constructivism: Developing tools for an effective classroom. Education, 130(2), 241-250.Retrieved from https://web-a-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=d66cabbe-04a4-423a-b7b4-d75e1be0de88%40sdc-v-sessmgr02

- ↑ Yan, J. H., Thomas, J. R., & Downing, J. H. (1998). Locomotion improves children’s spatial search: A meta-analytic review. National Library of Medicine, 87(1), 67-82. doi:10.2466/pms.1998.87.1.67.

- ↑ Lehman, G. (2011). Correlation of throwing velocity to the results of lower body field tests in male college baseball players. (Master’s thesis. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1039723685?pq-origsite=summon

- ↑ Lehman, G. (2011). Correlation of throwing velocity to the results of lower body field tests in male college baseball players. (Master’s thesis. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1039723685?pq-origsite=summon

Section 3:

Gerber, R. J., Wilks, T., & Erdie-Lalena, C. (2010). Developmental Milestones: Motor Development. Pediatrics in Review, 31(7), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.31-7-267

Healthwise. (2019, August 22). Milestones for 6-Year-Olds. HealthLinkBC. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/ue5723.

Healthwise. (2019, August 22). Milestones for 7-Year-Olds. HealthLink BC. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/ue5719.