Course:GRSJ300/2020/Past, Present and Future: Considering Historical Contexts, Current Uses, and Potential Directions of the Intersectionality Framework

Intersectionality is the theory, framework, and tool of analysis that encompasses the existence of multiple intersections of identity within the individual, and therefore highlights the nuanced, complex, and simultaneous experiences of oppression and marginalization one experiences. Intersectionality acknowledges that there are different identities within one social group, in which members can identify with more than one intra-grouping, and communicates that one identity can inform and alter the lived experience of other identities. In recognizing the different identities, one can observe the way that privilege and discrimination overlap, rather than adhering to distinct categories of identity or following additive models of oppression. Intersectionality encompasses all groups and identities, including but not limited to gender, race, sexuality, class, ability, socioeconomic status, and religion.

According Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term, intersectionality can be divided into three categories: representational, political, and structural intersectionality. Intersectionality can also be used as a framework to observe larger systems of oppression or privilege in the world around us.

History

1989

The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989, during the women’s suffrage movement, when she noticed that there was a lack of awareness for issues that intersected with feminism, such as race, class, and ableism[1]. In the movement for feminism, members from different communities were being marginalized, their voices silenced and their backgrounds dismissed, creating just one body instead of recognizing the different identities that inform experiences of being female.

"The problem with identity politics is not that it fails to transcend difference, as some critics charge, but rather the opposite - that it frequently conflates or ignores intragroup differences."

- Kimberlé Crenshaw[2]

Crenshaw first observed this problem among black women who were fighting for gender equality, and how their black identities were not being acknowledged by those fighting alongside them. Their stories were not recognized, in favour of white middle-classed women, and therefore not included as a part of the representation of the feminist movement. Seeing this problem, she published a paper in the University of Chicago legal forum[3], where she coined the concept of intersectionality. The word was created to define those who were simultaneously marginalized by their gender and their race; Specifically, black women who were fighting for gender equality.

1991

In 1991, Crenshaw published one of her widely known works, “Mapping the Margins”[4], where she further explained, through an examination of violence and injustice against women of colour, that intersectionality can be divided into three different categories: Representational, political, and structural. In each of these, a different approach to the subject can be taken, and different observations can be made. Crenshaw also states that intersectionality “provides the means for dealing with other marginalizations”[5], and is not limited to race and gender. It can be used to represent different aspects, such as disability, sexuality, class, and physical attributes.

1992- Present

Intersectionality is often used as a framework for scholarly investigation to demonstrate observations of how different identities are experienced in society. The framework is useful for analyzing media in popular culture as well as the efficacy of social movements in North America, such as Black Lives Matter and LGBTQIA2S+ movements, such as pride marches. In the modern day, where diversity is largely present and celebrated, intersectionality can help identify the struggles each individual person may face as a combination of their multiple identifications. Conclusively, the framework can be used to represent multiple marginalizations of different individuals and how they impact or empower those individuals.

Intersectionality and Popular Culture

Where Intersectionality Exists

Intersectionality is a framework that has found its way through popular culture since its emergence in scholarship. Within popular media, the intersectional framework has provided BIPOC communities a chance to be heard through series such as When They See Us (a series aimed at shining light on police brutality and discrimination), Sex Education (a forward-thinking series that takes place in a world in which multiple communities live together without racist bias), and many other popular culture outlets. As movements such as Black Lives Matter (BLM) gain traction, many are witnessing workplace changes, including increased amounts of racial diversity and cultural acceptance in companies. These changes are not limited to the workplace, but emerge within academic institutions such as universities, scholarship applications, and priority seating. Using the intersectionality framework, BIPOC communities are finally able to take a stance and stand together to fight against systemic and internalized racism. The intersectional framework emphasizes commonalities and creates solidarity among multiple groups of people[6]. It helps individuals understand the plight another human is going through due to aspects like race, culture, gender, and class. Not only has it helped dissipate much of the internalized racism felt by members of BIPOC communities, especially in westernized countries, but it has also given many people who identify with minority groups the platform to continue producing discourse and engaging in important conversations.

Portrayal of Racial Inequality

These very conversations are innately uncomfortable and are often a psychological trigger for many. Ignorance of intersectionality has historically led to racial inequality. This has surfaced in many forms and, to illustrate them, popular culture has depicted these moments astoundingly. What is often overlooked is the importance of the medium through which discussions of simultaneous inequality take place. This can include outlets such as social media, social gatherings, news broadcasts, and popular culture. They do not just distribute information and explain the importance of movements such as BLM, but they urge their audience internalize the meaning of these movements. By putting the viewer into the shoes and lives of the characters in these films that employ an intersectional framework, the audience can empathize with minority communities. One film that does an excellent job of allowing the audience to empathize and understand the plight minority communities go through is Moonlight (2016). The protagonist is seen struggling in his adolescence with family, bullying, and his sexual orientation within his own racial community. The film illustrates that other forms of discrimination are felt alongside and at the same time as racism. Laverne Cox, a transgender woman of colour who rose to fame as an actress in Orange is the New Black, is herself an advocate of this, as she said that it was usually people within her own community that policed her gender and discriminated her for her sexuality [7].

All in all, society is moving forward to create solidarity among people of all races. Although there is much work to be done, popular aspects of media culture are employing ways of spreading awareness about the importance of using the intersectional framework as a tool of analysis to rid the world of inequality and advancing humanity forward.

Social Movements

How Intersectionality is Used

Intersectionality plays a key role in framing social movements and their approach to social change. As a theory, it is used to encourage the inclusion and representation of minority groups, therefore uniting a group of people who share similar experiences of oppression due to a common social identity. Intersectionality is a tool that can help identify discrimination due to one’s social identities, and examines how it can impact a person’s rights and opportunities. This allows others outside of the oppressed group to gain greater understanding of minority groups' disadvantages due to reasons outside of their control. This understanding of inequality can help promote the building of solidarity and allyship between communities. We can see the demonstration of this solidarity through the organization of peaceful protests and active approaches to educating the privileged about the presence and experience of inequality. We observe this in social movements such as feminism and the Black Lives Matter movement.

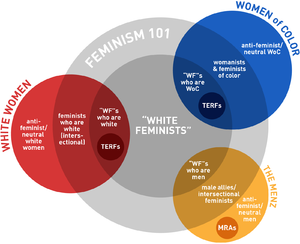

The Feminist Movement

Feminism is the advocacy of women's rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes. Throughout history, and even today, just having the social identity of a woman can lead to less respect, unequal opportunities in a variety of institutions, and assumptions of weakness. Although women may be from different classes or races, they do share one experience: The disadvantages that come along with being born into the world as female. An author, feminist and social activist, bell hooks, discusses in her writing, “Visionary Feminism”[8], the importance of women realizing the combination of race, ethnicity, class, and gender when determining the life experiences that women will encounter. She speaks to how, in the past, white women of higher class ignored or disregarded the work of women of colour, accusing their work, which promoted feminism from a gender-race-class perspective, as shifting the focus away from the feminism movement. With white female scholars understanding that lower class women of colour face challenges that white women do not because of the intersections of class, race and ethnicity with their gender, great strength continues to be brought to the feminist movement. In order for the feminist movement to be successful, women must utilize intersectionality to build allyships with women of colour, LGBTQ women, and women belonging to any other oppressed groups. A social movement cannot be effective if not all members of the group are supported, included, and provided with a voice equally.

Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter (BLM) is a social movement advocating against police brutality and other forms of structural violence against black people. Intersectionality is very important here, as not all individuals have experienced, or will experience, the hardships and disadvantages black people wrongly face. Employing an intersectional framework can help people understand how racial identity significantly impacts an individual’s life. This can help with establishing allyships, constructing methods of organizing and coalition-building, and helping non-oppressed groups, such as White people, understand how their race and ethnicity allow them to have greater privileges and rights than black people. Knowing that they have this unique access to rights and privileges based on race alone can bring awareness to how wrong and unjust racism is. This can also encourage individuals with White privilege to use their social power to stand up and amplify voices of those who have been silenced.

(Dis)ability Representation in Media and the Intersectional Framework

The Definition of (Dis)ability

(Dis)ability, as a term, meaning, and construct, continues to shift across space and time, coming into conversation with intersectionality as one of the simultaneous experiences, identities, or oppressions an individual can face. This notion of (dis)ability with the parenthetical adjustment, according to Sami Schalk, is a reference to the dominant social system of bodily and mental norms or expectations pervading the contemporary world, which include notions of ability and disability [9]. Therefore, Schalk states that disability without the parentheses merely references disability as impairment, rather than capturing a variety of lived experiences and identities [9]. (Dis)ability as a term and as a linguistic corollary also marks the mutual dependency of the meanings of disability and ability in order to define one another [9]. Schalk believes that the parenthetical adjustment “visually suggests the shifting, contentious, and contextual boundaries between disability and ability" [9]. The parentheses therefore emphasize the importance of an intersectional framework, as this linguistic tool allows for a critique of ability as a vector of power, just like race and gender, in defining experience and identity.

Ableism and Disablism

In discussing notions of abled and (dis)abled experience, it is important to highlight the difference between ableism and disablism.

Ableism refers to the notion that positive meaning is automatically ascribed to the able body [10]. This is evident in the validation and affirmation we see of the able body in the construction of public facilities, availability of job opportunities, and access to residential areas.

On the other hand, disablism seeks to associate negative meaning with (dis)ability [10], and this reveals itself in the harmful tropes, stereotypes, and demonization of (dis)ability in the media, popular culture, policy, infrastructure, and other facets of interpersonal, public, and systemic life.

(Dis)ability and an Intersectional Framework

In her work, Schalk explores the potential imaginings and re-imaginings of (dis)ability with different intersections of identity through speculative fiction. She considers the possibility of changing narratives of (dis)ability, race, and gender, and ultimately changing the way marginalized individuals are represented and conceived in contemporary cultural production, in order to shift the way (dis)abled individuals are spoken about, treated, and understood [9]. Schalk therefore attempts to unite disability studies, or the interdisciplinary investigation of (dis)ability as a socially constructed phenomenon and systemic social discourse which governs how (dis)abled individuals are labelled, valued, and represented, with intersectional identities of race, gender, and sexuality, to move away from dominant narratives of white experience [9].

These important ideas of intersections of identity with (dis)ability have been taken up within media and representation, as well as in movements such as Ramp Your Voice! and the Disability Visibility Project. The Disability Visibility Project (DVP) is an online space that amplifies, shares, and creates nuanced, complex, and real narratives, creations, and media by the (dis)abled community [11]. The DVP state that they believe “that disabled narratives matter and that they belong to them," therefore claiming ownership and their own voice in composing narratives of (dis)ability. The DVP also create (dis)abled media from recorded oral histories, and publish “original essays, reports, and blog posts about ableism, intersectionality, culture, media, and politics from the perspective of disabled people” [11]. The DVP represents an effort to share and express the true lived experiences of people with (dis)abilities, so the perceptions of (dis)ability become humanized to others. The founder of Ramp Your Voice!, Vilissa Thompson, is a Black disabled woman, whose organization speaks to individuals who experience multiple intersections of oppression, alongside their (dis)ability [12]. Thompson and her organization provide workshops, consultations, and group discussions to various audiences to discuss the experiences of (dis)abled women and women of colour, covering topics like the movement #DisabilityTooWhite and its implications, empowering women of colour with disabilities, and considering sexuality and womanhood of disabled females [12].

Challenges, Contradictions, and Flaws of the Framework

Disciplinary Feminism “Taking Over” Intersectionality

Over the years there’s been an increase in discourse surrounding the idea that disciplinary feminism has aimed to “take on” or “take over” intersectionality. However, it is doing so as a means to marginalize those trying to reconnect it with its initial vision. The original vision of intersectionality was grounded in the political subjectivities and struggles of less powerful social actors facing multiple intertwined oppressions[13]. If disciplinary feminism is able to gain traction, it will be at the expense of less powerful social actors, and will instead benefit White feminist scholars. This moves intersectionality away from the radical politics that it emerged from and that it is rooted in, including black feminist practice and the efforts of the Combahee River Collective. It strays from the politics of organizing and the amplification of marginalized voices, instead conforming to colonial institutions of white supremacy.

Intersectionality as a “Buzzword”

The increasing popularity of intersectionality has also led it to become a “buzzword.” This is a concept that has become fairly common across disciplines and that has led intersectionality to become widely interpreted, tokenized, and disarticulated. When one considers intersectionality emerging as a tool to counter multiple oppressions, it is easy to see why there are so many narratives surrounding it. This has resulted in the theory being used in a variety of different contexts and, more often than not, has led to its deviation from creator Kimberlé Crenshaw’s definition and its history. Furthermore, it helps support the idea that the concept has been distorted or misused to such a degree that the term has become meaningless and now requires replacing[14].

Diversity Is Not Intersectionality

A common issue with assumptions of intersectionality is that it is often thought of as being synonymous with diversity. However, this is not the case. The thought that diversity and intersectionality are synonymous is actually a neoliberal approach to being inclusive and is marketed to promote post-racial blindness. In actuality, this thought ornamentalizes intersectionality. According to Sirma Bilge, the superficial deployment of intersectionality undermines intersectionality's credibility and potential for addressing interlocking power structures and developing an ethics of non-oppressive coalition-building and claims-making[13]. Simply put, ornamental intersectionality utilizes the framework solely for representation purposes, in order to claim suggestive action towards diversity and inclusion. Intersectionality is not just about making marginalized people and groups visible, but is about acknowledging, interpreting, and fighting systemic and institutional oppression.

Conclusion

Intersectionality functions as useful and essential framework, tool of analysis, and theory for nuanced and truthful representation of marginalized groups in contemporary society. It can be used to demonstrate that interlocking identities are not reminiscent of an additive model of oppression, but a fluid matrix of marginalization, where each identity impacts the lived experience of other identities. Therefore, intersectionality emphasizes and acknowledges the importance of imagining simultaneous existences that contextualize multiple axes of experience, rather than confining individuals to the notion of living single-axis lives. Although there is still much work to be done in the form of education, conversation, solidarity building, and other forms of resistance, intersectionality paves the way forward for imagining and conceptualizing human experience, in order to achieve a future of equality and acceptance.

References

- ↑ Perlman, Merrill (October 23, 2018). "The origin of the term 'intersectionality'". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Kimberle (July 1991). "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color". Stanford Law Review. 43: 1242 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "What is Intersectionality?". Grinnell College. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ↑ Coleman, Arica L. (March 28, 2019). "What's Intersectionality? Let These Scholars Explain the Theory and Its History". Time. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Kimberle (July 1991). "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color". Stanford Law Review. 43: 1299 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Carbado, Devon W, et al. "INTERSECTIONALITY: Mapping the Movements of a Theory." ProQuest (2013): 303-312.

- ↑ Cox, Laverne. Black, LGBT, American: Laverne Cox. 15 July 2013. 22 October 2020.

- ↑ hooks, bell (2014). "New Edition Seeing the Light: Visionary Feminism". In Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center: XI–XVI.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Schalk, Sami (2018). "Introduction". Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women's Speculative Fiction. London: Duke University Press. pp. 1–31.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Berghs, Maria; Chataika, Tsitsi; Dube, Kudakwashe; El-Lahib, Yahya (2020). "Introducing Disability Activism". In Berghs, Maria; Chataika, Tsitsi; El-Lahib, Yahya; Dube, Kudakwashe (eds.). The Handbook of Disability Activism. London: Routledge. pp. 3–20.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 The Disability Visibility Project. "About". Disability Visibility Project. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ramp Your Voice!. "Empowering People with Disabilities". Ramp Your Voice!. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bilge, Sirma (Fall 2013). "Intersectionality Undone: Saving Intersectionality from Feminist Intersectionality Studies". Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 10: 405–424.

- ↑ May, Vivian M. (2015). Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries. New York: Routledge. p. 108.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community. |