Course:GEOS303/2023/Tonga

Introduction

Location and Background

Located in the heart of the South Pacific Ocean, the Kingdom of Tonga comprises of an archipelago with various geological features and unique landscapes[1]. Tonga stretches between 18° and 23° south latitude and 173° and 176° west longitude, with 150 islands totaling to 696.707 kilometers squared - or 269 square miles[2]. These limestone islands are either very flat and sandy, created from an uplifted coral formation or have volcanic typography[3]. Tonga is known for it’s landscapes, being diversified in beaches, cliffs, mountains, and rainforests[4]. In terms of marine environment, the islands are located on the Tonga-Kermadec Ridge, which is 3000km long active subduction boundary[4]. Additionally, there is the Tonga Trench (second deepest in the world) and the underwater Tonga volcanic arch[4]. The capital of Tonga is Nuku’alofa, combining nuku “residence or abode” and alofa “love”[3]. Tonga is made of three districts, Ha’apai, Vava’u, and Nua islands[4]. These islands got the nickname “Friendly Islands” from Captain James Cook in 1773[3].

Overview of Climate and Occurrences

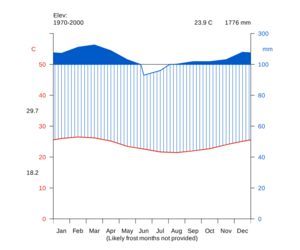

In terms of climate and natural occurrences, Tonga adheres to most of the common qualities of islands within the Southern Pacific. Tonga is affected by the trade winds and Pacific Convergence Zone[5], which cause a warm season from December to May, and a cool season from May to December[3]. The wet season is from November to April, with the wettest months being January to March with precipitation over 250mm monthly[5]. The temperature fluctuates with seasons, from 21 degrees celsius to 26 degrees celsius annually[5]. In terms of natural disasters, Tonga is highly susceptible to earthquakes, droughts, cyclones, and volcanic eruptions[3]. These islands were formed on the northern end of an active volcano island arc, some positioned around 100km above a westward dipping seismic zone[6]. The western islands vary in volcanic activity, moderate being Fonualei with recent activity, to Niuafo’ou which require evacuations[3]. Furthermore, the eruptions in Tonga can be abundantly intense that they can influence the creation of new islands. For example, in 2014, a surtseyan eruption near the Tonga-Kermadec Islands caused the formation of Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha'apai[7]. When El Niño Southern Oscillation occurs, catastrophic droughts and intense cyclones affect Tonga[5].

Biomes, Ecosystems, and Climate

Biomes

The dominant terrestrial biomes of Tonga are tropical rainforests, mudflats, and mangrove forests. Tropical lowland forests cover 12.5% of the total land area - being the dominate biome among the Vava'u island groups [8]. Lowland rainforest stands are particularly extensive on the largest island, the terraced limestone island of 'Uta Vava'u, which supports a number of coastal forests similar to those found on low coral islands and smaller volcanic islands, as well as patches of the once more extensive tropical hardwood forest populations that have disappeared from less-relief islands. [9]

In Tonga, intertidal mud flats and mangrove forests are critical ecosystems for nearshore marine ecosystems. [10] In previous records, it's been depicted that Tonga once hosted 1000 hectares of Mangrove forests. However, recent coastal reclamation has reduced the mangrove coverage to 336 hectares [11]. Tonga hosts 10 mangrove species, the two most frequent being Rhizophora samoensis and Rhizophora stylosa [11].

Tonga obtains a variety of marine and coral reef biomes. The Vava'u and Ha'apai island groupings are among several coral islands that have evolved along the eastern ridge. There are two types of coral islands: low coral islands and elevated coral islands. [12] Tonga's coastal waters and coral reefs are included in the marine and coral reef biome. The Tonga trench, situated east of the Tonga ridge, is the planet's second deepest, attaining a maximum depth of 10,882 m in a region known as "Horizon Deep." It is 1375 kilometres long and 6000 metres deep on average [13]. The Tonga Trench is habitat to a diverse range of marine life, including fish species, sea cucumbers, and marine worms, and it serves as a destination for marine mammal migrations and potential reproductive grounds for fish species.[14]

Ecosystems

As for Tonga's ecosystems, the island is home to many ecosystems that are interconnected. For example, the mangrove forests act as a defence against storms and erosion - they also play as a feeding area for juvenile fish. Tonga sustains various types of coral reefs, the most well-known being the fringing reefs along the coastline of the Ha'apai Group of islands. These are notably diverse, home to more than 250 species of coral[15]. As non-reef marine habitats, the islands also contain seagrass beds which support species of marine life such as dugongs or sea turtles. As for terrestrial ecosystems, Tonga is dominated by early successional rainforests, with late-successional lowland rainforests appearing in some areas of high elevation. However, Tonga’s landscape has been changing for several years due to human activity such as deforestation, overfishing and pollution, which has caused decreases in the reef and forest area on the islands.[16]

Climate

Volcanic eruption in 2021

Tonga’s annual mean temperature varies from 26-23 deg C, with its wet season from November to April and dry season from May to Oct[17]. Around 60-70% of Tonga’s rainfall occurs during its wet season, with little to no rainfall during dry season and rainfall exceeding 250mm in January, February and March[18]. The SouthWest Pacific area, where Tonga is located, is susceptible to frequent tropical cyclones, leading to high amounts of precipitation in the area[19]. Due to this, Tonga’s climate is mostly influenced by its geographical region, which is prone to tropical cyclone occurrences and trade wind effects, as well as effects of the movement of the South Pacific Convergence Zone[17]. Changes in Tonga’s climate characteristics over time include sea level rise of around 6mm/yr, and an overall decrease of 19% in long term rainfall[20]. Tonga has also seen an increase in frequency and severity of tropical cyclones, and is prone to other disasters such as tsunamis, earthquakes, and droughts[20].

Tongatapu, Ha'apai, and Vava'u are coral limestone islands that are underlain by old volcanic rocks. Volcanic eruptions pose a threat to atmospheric conditions, which have the potential to increase global surface temperatures with large eruptions releasing high amounts of sulfur dioxide.[21] Overall, the geographic location of the island of Tonga affects its precipitation levels, climate, and in turn ecosystem characteristics.

Considering the current climate crisis, an increased intensity of these natural disasters, with warming temperatures, may further impact the islands of Tonga.[19]

Diversity

Species Richness

Biodiversity in Tonga has changed throughout the time, impacted by volcanic activity, human settlement, and other factors. The Kingdom of Tonga lies upon volcanic zones, affecting species development and survival.[22] Along with volcanic activity, the impacts of human settlement are seen across the islands. Species native to Tonga are found on volcanic islands with high elevation, unlike those disturbed by human interaction which have higher rates of introduced species.[22] The species-area richness theory is also present within the islands of Tonga, with larger islands having higher numbers of species richness.[22] While Tonga has a rich history in biodiversity, the future of biodiversity on the island is currently at risk due to climate change. The World Bank has identified various areas of concern for the island of Tonga, including sea-level rise, sea-temperature rise, and the impacts these outcomes will have on the diversity in Tonga.[23]

Native and Invasive Species

Tonga is home to a number of native species. Many of Tonga's native trees perform essential functions in the forest ecology, providing habitat and food for a variety of species. [24] The Tongan Whistler (Pachycephala jacquinoti) lives in the forest canopy and helps to control pester populations. [25] Polynesian Starlings (Aplonis tabuensis) are mostly frugivores that aid in the dissemination of seeds for a variety of plant types. [25] The Pacific Boa (Candoia bibroni) is a predatory which serves to keep smaller creatures like lizards and rodents in balance. [24]

Humpback whales, in addition to natural vegetation and fauna, are native to the island of Tonga. These migratory species primarily depend on Tongan waters for breeding. They contribute to the balance of marine ecosystems whilst having a considerable impact on smaller creatures through their feeding habits.[26] The extinction of one of these native species can have a domino effect on the ecosystem, potentially altering its balance.[27]

Invasive species are the primary threat to native species. The Mile-a-minute vine (Mikania micrantha), a fast-growing vine that colonises by encasing other plants, is one of the invasive species found in Tonga. [28] Given its rapid growth, this vine has the potential to outcompete and inhibit native species, thereby diminishing biodiversity and altering habitat structures. [29] Another invasive species, the Indian Myna (Acridotheres tristis), competes with local birds for nesting grounds and nutrition. (Atsawawaranunt et al., 2023) Its aggressive nature has the potential to displace native species. [30] The Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) additionally thrives on corals by extending their stomachs over them. [31] Outbreaks may destroy coral reefs, reducing coral cover and negatively impacting the overall reef ecology. [32]

These invasive organisms have caused havoc on the ecosystem. Invasive species may outcompete native species for resources, causing native species to decline or even perish. Some invasive species may grow into predators of native species that lack evolutionary defences to them. Invasive species could bring about new illnesses that harm native populations. Certain invasive species may additionally lead environments to become unsuitable for native species.

Biotic Interactions

Due to Tonga’s incredible biodiversity, there is a wide range of biotic interactions occurring between the species that inhabit its island. Cleaner wrasses, Labroides spp, is a small fish known to be found among coral reefs, that have a mutualistic relationship with other larger fish in their habitats.[33] These fish feed on dead skin and parasites so that the cleaner fish can eat, while also benefiting the other fish in the reef. Another interesting example of biotic interactions in Tonga was the addition of the polyphagous parasitoid Aphidius colemani., as an attempt to control a pest known commonly as the Banana aphid, Pentalonia nigronervosa.[34] There are also many examples of predation present on the islands, and one of the most notable predators is the banded sea krait, Laticauda colubrina. Known colloquially as the yellow-lipped sea snake, it is a venomous creature that feeds primarily on small fish and eels.[35]

Introduction to Species Conservation

Tonga’s marine ecosystems are mainly in danger due to overfishing and exploitation through an increasing population, as well as with effects of natural disasters[36]. To combat human impact Tonga has introduced a Special Management Area (SMA) program, that addresses fishing through a community based management approach [37]. This involves the protection of marine ecosystems through exclusive access to fish habitats in return for management of the areas[37], in an effort to conserve ecosystem health and biodiversity with an increasing population[36]. Tonga’s forest ecosystems undergo similar conservation efforts, with the inclusion of natural disaster relief initialives and resources as well as some protected land areas[38]. Tonga’s harvesting practices as well rely mainly on coconut timber resource availability, with limited harvesting areas and many inaccessible land areas under forest protection and conservation acts[38].

Human influences

Climate Change

Anthropogenic climate change will and is currently impacting ecosystems across the globe. Tonga, as like many other countries around the world, are susceptible to these changes. The case of Tonga is interesting as impacts felt are often not caused by local emission sources.[39] Among others, biodiversity loss is noted as a risk in Tonga due to climate change.[23] Tonga, being located in the SouthWest Pacific may experience more frequent storms and floods, as well as increased sea level rise.[40] Tonga, being made up of islands, has certain susceptibilities to climate change. For example, sea level rise may lead to range size decrease and habitat loss.[41] Biodiversity is also threatened on small islands given the inability for organisms to easily migrate.[42] These threats to biodiversity in Tonga call for a global effort in mitigating the effects of climate change.

Marine Ecosystems

Like in the most oceanic regions, overfishing plays a large role in threats to marine environment. The health and wellness of the coral reefs in Tonga is often measured by its species richness of its fish population.[43] As a result, overfishing has a direct impact on the state of its coral reefs. Most of the fishing populations are harvested through commercial fisheries which have been responsible for the decline in fish biodiversity and density in multiple constituencies in the Tongatapu, Ha’apai, Vava’u islands.[44] Many islands within the kingdom of Tonga have implemented several management strategies to combat overfishing and dangerous fishing practices.[45] Some of these methods include introducing limits on fish harvests, greater authority to SMA committees, and implementing institutional mechanisms to create better cooperation between communities.[46]

Plastics

In relation to fishing, ocean pollution also poses a threat to Tonga’s ecosystems through the consumption of microplastics by marine animals[47]. Mircoplastic consumption refers to small pieces of plastic that are mistaken for food or otherwise unintentionally consumed by marine animals and found in their digestive systems[48]. These microplastics can cause blockages in animal’s digestive tracts and emit toxins into the animal once consumed, which can subsequently affect other species such as humans that consume these marine animals[48]. A study conducted in Vava’u found a high concentration of microplastics present in Tonga’s tidal sediments, suggesting that Tonga is at risk of high microplastic contamination within its marine ecosystems[47].

Urbanisation

Nuku’alofa, situated on Tongatapu Island, currently accommodates approximately a third of Tonga’s population. Forecasts indicate this figure could rise to 40% by 2030, owing to ongoing migration from the outer islands[49]. This migration trend mirrors the global shift from rural to urban regions, driven by factors like globalization and the promise of urban amenities such as employment opportunities, improved education, and healthcare facilities. Tonga experiences this trend; however, the available urban space struggles to absorb the influx of rural migrants, leading to the emergence of informal settlements along coastal areas originally unsuited for residential purposes [50].

Urban expansion in Nuku’alofa faces obstacles due to natural calamities like earthquakes and tropical cyclones, causing substantial damage and impeding development efforts. Consequently, living conditions for many Nuku’alofa residents deteriorate, amplifying the demand for enhanced urban infrastructure [49]. Expanding the city's boundaries encounters challenges owing to limited available land, mostly confined to peripheral agricultural and ecologically sensitive zones. Ongoing initiatives, such as the Nuku’alofa Reconstruction Project and the Integrated Urban Development Sector Project (IUDSP), aim to improve existing infrastructure[51].

The city also grapples with significant traffic congestion due to an increased number of vehicles on main roads and in the town center. Insufficient traffic management, particularly inadequate parking controls, exacerbates congestion. Additionally, inadequate road drainage and poor maintenance lead to frequent road flooding [51].

Tonga’s case of urbanization stands out because widespread urbanization isn't economically imperative. The fertile land historically sustained households, often generating surplus food for distribution or storage [52]. Tonga's approach to urban planning contrasts with the conventional 'top-down' method, favoring a 'bottom-up' approach that emphasizes extensive public and internal consultations. This approach prioritizes cultural knowledge and practices, preserving the island nation's unique identity amidst the pressures of urbanization[50].

Conservation Projects

Rat Removal

Tonga is home to varying conservation projects across islands in order to maintain biodiversity within the country. Within Tonga, it has been noted that rats can have a mal-effect on seed dispersal, as they eat seeds rather than disperse them.[53] Invasive rats also prey on eggs and cause decreases in bird populations.[54] Late Island, where the removal of rats took place, serves as habitat to endemic species.[55] Due to the negative consequences of increased rat populations, Tonga began the largest rat removal project ever completed in the Pacific Region.[55] The removal of invasive rats on islands in Tonga is said to protect resilience to climate change, increase bird populations, and may increase fish numbers by up to 50%.[54] Highlighted in this project is the implementation of community consultation as an important component.[56] Taking success stories such as that on the Late Island of Tonga can prove a useful example for further work on invasive species and conservation.

GEF R2R Project

The Global Environment Facility [GEF] Ridge to Reef [R2R] project is an ecosystem conservation effort of the Fanga'uta Lagoon Catchment on Tongatapu Island, that is a response to previous water management approaches implemented through the Pacific IWRM[57]. The Pacific IWRM initiative focused on water pollution through the implementation of sanitation systems, however some of these systems were unsuccessful and many were seen to have negative effects on the ecosystem due to leaking and overflowing of septic tanks[58]. The goal of the GEF R2R project was to gain proper knowledge to improve biodiversity conservation efforts of the lagoon ecosystem through an integrated costal, land, and water approach, by focusing on coastal management plans[57]. This project focused on monitoring and improving the effectiveness of current water-based management strategies, with an aim to strengthen environmental factors of carbon storage, climate resilience, and ecosystem service protection in the area[58]. The project involved three different strategies: monitoring stress reduction measures' effectiveness through data collection on sanitation systems, increase donor investments through capacity building at both a local and national scale, and establishing costal zone management plans by identifying fisheries at priority sites[58]. This project was completed in 2019, and resulted in overall monitoring, funding, and knowledge success with regards to each strategy implemented[59]. Its success provides crucial information that is now used for conservation planning, and is currently being implemented in Vavau'u as a result of its success[59].

Vava'u Ocean Initiative

The Vava'u Ocean Initiative, launched in 2017, is a collaboration between the Government of Tonga, the Vava'u Environmental Protection Association, and the Waitt Institute. [60] The programme intends to promote long-term economic development compatible with marine protection. Its key goals are fisheries management, long-term ocean planning, and biodiversity preservation.[60]

It comprises three key areas of concentration:

- Marine Spatial Planning (MSP): MSP in Tonga, which began in 2015, entails allocating marine spaces for diverse activities to balance ecological, economic, and social goals[60] [61]. This process includes resource valuation and legislative review, guided by international frameworks such as the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and the Convention on Biological Diversity[61] . Using techniques such as satellite imaging, remote sensing, and habitat mapping, MSP aids in the management of key habitats such as coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and mangrove forests [62].

- Special Management Areas (SMAs) for Community Fisheries: SMA development helps local communities to use and protect marine resources sustainably. [63] These regions, including habitats such as coral reefs and mangroves, are managed collaboratively by the state and communities, resulting in significant improvements in fisheries trends and resource recovery through community-based collaboration.[64]

- Supporting Scientific Research: The programme largely relies on scientific research to assist decision-making and management practises for successful conservation strategies and resource utilisation that is sustainable. [60]

The Vava'u Ocean Initiative takes an integrated conservation approach, integrating ecological sustainability with community participation and economic development. [60]

The programme has made a substantial contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially in light of Tonga's unique environmental and socioeconomic constraints. [61] Positive outcomes, such as higher fish stocks and reduced fishing attempts, have been reported by local people, suggesting the viability of the initiative's resource management measures. [63]

Tuna Fisheries

Tonga relies heavily on Tuna fisheries to boost the nation’s economy, as well as for food security and the general wellbeing of inhabitants, primarily as a way to sustain its fisheries without having to fish the reef and lagoon species that have since become endangered.[65] In recent years, there is now a demand for policies to prevent the same thing from happening to its Tuna population as a result of overfishing. One of the major concerns that comes up in the conservation efforts of the Tuna population is balancing the wants and needs of all effected parties, from the large fisheries, to the local fisheries, to the nation’s government, all the way to the international powers like the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, the main authority overseeing Tuna management within the region.[66] The implementation of the Tonga National Tuna Fishery Management and Devolpement Plan (TMDP) is designed to attempt to balence the interest of all these groups, mainly by implementing catch regulations and limiting the quantity of foreign licensed vessels that can fish within designated areas. While the successes of these efforts are relatively difficult to quantify, and there have been some calls for more unity on these efforts, the steps that Tonga is taking to ensure the safety of the fish in their environment have been considered commendable and steps well worth taking.[67]

Tonga Turtle Project

The Tonga Turtle Conservation Project, led by Kate Walker, aims to establish a community-based turtle conservation initiative and an education/outreach program in Vava’u, Tonga[23]. The goals are to assist the nesting population of turtles on Vava’u and discourage illegal turtle fishing. The project concentrates on four turtle species in Tonga: hawksbill, green, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles, with hawksbill and green turtles being the primary nesters[23].

The region has legislation protecting turtles, limiting harvesting to a specified season for male turtles and completely banning the harvesting of females and all nests throughout the year[23]. Despite laws, there is a market for turtle meat, leading to illegal harvesting, including during closed seasons and of females and eggs[23].

The specific problems at hand are[23]:

- Illegal harvesting of nests and turtles during closed season

- Lack of enforcement of legislation during the closed and open seasons on size limits, sex, etc

- Lack of care by communities to protected nesting and foraging grounds

- Placement of static nets for fishing leading to turtle by-catch

The project's mission is to manage these issues through various objectives and action plans[23]. The overarching strategy involves breaking down long-term goals into shorter-term objectives, forming the basis for a multi-year strategic action plan. The initiative includes engaging with local communities, conducting outreach in schools, and implementing restrictions to enforce and enhance turtle protection laws[23].

Tonga Waste Management and Pollution Control

Mone Lapao'o, working with Tonga's Department of Environment, leads actions to combat marine plastic pollution in the island nation[68]. Lapao'o's focus is on eliminating the sources of plastic waste within Tonga's borders, emphasizing the enforcement of the Waste Management Act, restricting dumping, and avoiding plastic incineration[68]. Cleanup initiatives, including the Beat Pollution Trash Challenge, along with awareness campaigns through media and school visits, comprise critical elements of his strategy[68]. Lapao'o highlights the significance of education and awareness in addressing the plastic waste problem, expressing motivation driven by the belief that healthy oceans are important for Tonga's well-being[68]. He calls for individual responsibility and increased awareness, urging everyone in Tonga to quit littering and adopt more responsible perspectives to collectively reduce plastic pollution[68].

References

Please use the Wikipedia reference style. Provide a citation for every sentence, statement, thought, or bit of data not your own, giving the author, year, AND page. For dictionary references for English-language terms, I strongly recommend you use the Oxford English Dictionary. You can reference foreign-language sources but please also provide translations into English in the reference list.

Note: Before writing your wiki article on the UBC Wiki, it may be helpful to review the tips in Wikipedia: Writing better articles.[69]

- ↑ Bryan, W; Stice, B; Ewart, A (10 March 1972). "Geology, petrography, and geochemistry of the volcanic islands of Tonga". Journal of Geophysical Research. 77(8): 1566–1585.

- ↑ Kaeppler, Adrienne L (1968). "Rank in Tonga". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 108(2): 168–232.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "The World Factbook - Tonga". CIA.gov. 6 December 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Kästle, Klaus (nationsonline.org). "Map of Tonga". Nations Online Project. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Tonga Climatology". World Bank.

- ↑ Ewart, A.; Bryan, W. B.; Gill, J. B. (1 October 1973). "Mineralogy and Geochemistry of the Younger Volcanic Islands of Tonga, S.W. Pacific". Journal of Petrology. 14(3): 429–465.

- ↑ Garvin, J. B.; Slayback, D. A.; Ferrini, V.; Frawley, J.; Giguere, C.; Asrar, G. R.; Andersen, K. (11 March 2018). "Monitoring and Modeling the Rapid Evolution of Earth's Newest Volcanic Island: Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha'apai (Tonga) Using High Spatial Resolution Satellite Observations". Geophysical Research Letters. 45(8): 3445–3452.

- ↑ "Tonga Forest Information and Data". Mongabay.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ Fall, Patricia L; Drezner, Taly Dawn; Franklin, Janet (June 2007). "Dispersal ecology of the lowland rain forest in the Vava'u island group, Kingdom of Tonga". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 45 (2): 393–417.

- ↑ Ellison, Joanna C.; Stoddart, David R. (1991). "Mangrove Ecosystem Collapse during Predicted Sea-Level Rise: Holocene Analogues and Implications". Journal of Coastal Research. 7 (1): 151–165.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Aholahi, Hoifua (30 September 2013). "Mangroves of Tonga: Coastal Development Threatens Mangrove Ecosystems". Living Oceans Foundation.

- ↑ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ Leduc, Daniel; Rowden, Ashley A; Glud, Ronnie N; Wenzhöfer, Frank; Clark, Malcolm R; Kitazato, Hiroshi (1 October 2016). [10.1016/j.dsr.2015.11.003 "Comparison between infaunal communities of the deep floor and edge of the Tonga Trench: Possible effects of differences in organic matter supply"] Check

|url=value (help). Deep-sea Research Part I-oceanographic Research Papers. 116: 264–275. - ↑ Stone, K., Fenner, D., LeBlanc, D., Vaisey, B., Purcell, I., & Eliason, B. (2019, January 1). Chapter 30 - Tonga (C. Sheppard, Ed.). ScienceDirect; Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081008539000385

- ↑ Peirano, A., Barsanti, M., Delbono, I., Candigliota, E., Cocito, S., Hokafonu, T., Immordino, F., Moretti, L., & Matoto, A. L. (2023). Baseline assessment of ecological quality index (EQI) of the marine coastal habitats of tonga archipelago: Application for management of remote regions in the Pacific. Remote Sensing, 15(4), 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15040909

- ↑ Franklin, J., Wiser, S. K., Drake, D. R., Burrows, L. E., & Sykes, W. R. (2006). Environment, disturbance history and rain forest composition across the islands of Tonga, Western Polynesia. Journal of Vegetation Science, 17(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2006.tb02442.x

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 “World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal.” Climatology | Climate Change Knowledge Portal, 2021, climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/tonga/climate-data-historical#:~:text=Tonga%27s%20climate%20is%20tropical%20and,mm%20of%20rainfall%20per%20month

- ↑ “Climate Summary Tonga.” Met.Gov.To, Tonga Meteorological Service – Ministry of Civil Aviation, www.met.gov.to/index_files/climate_summary_tonga.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Deo, A., Chand, S., Ramsay, H., Holbrook, N., McGree, S., Magee, A., Bell, S., Titimaea, M., Haruhiru, A., Malsale, P., Mulitalo, S., Daphne, A., Prakash, B., Vainikolo, V., & Koshiba, S. (2021). Tropical cyclone contribute to extreme rainfall over southwest Pacific Island nations. Climate Dynamics, 56(11-12), 3967-3993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-021-05680-5

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ashneel S., Lal A., and Datta B. "Evaluating the Impacts of Climate Change and Water Over-Abstraction on Groundwater Resources in Pacific Island Country of Tonga." Groundwater for Sustainable Development, vol. 20, 2023, pp. 100890.

- ↑ Jenkins, S., Smith, C., Allen, M., & Grainger, R. (2023). Tonga eruption increases chance of temporary surface temperature anomaly above 1.5 degrees celsius. Nature Climate Change, 13(2), 127-129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01568-2

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Fall, P.L., & Drenzer, T.D. (2013). Species Origin, Dispersal, and Island Vegetation Dynamics in the South Pacific. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(5), 1041-1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.805084

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 World Bank. (2021). Climate Risk Country Profile: Tonga. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/country-profiles/15823-WB_Tonga%20Country%20Profile-WEB.pdf Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 24.0 24.1 One Earth. (n.d.). Tongan tropical moist forests. https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/tongan-tropical-moist-forests/

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 BirdLife International. (2020). Country profile: Tonga. https://www.birdlife.org/

- ↑ Tonga Wildlife. (n.d.). Plants. https://tongawildlife.weebly.com/plants.html

- ↑ Worthy, T. H., & Burley, D. V. (2020). Prehistoric avifaunas from the kingdom of tonga. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 189(3), 998-1045. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz110

- ↑ Pacific Pests, Pathogens & Weeds. (n.d.). Mile-a-minute (Mikania micrantha). LucidCentral. https://apps.lucidcentral.org/ppp_v9/text/web_full/entities/mileaminute_466.htm

- ↑ Space, J. C. (2002). Report to the government of samoa on invasive plant species of environmental concern / james C. space and tim flynn. Hawaii: U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry.

- ↑ FEARE, C. J., BRISTOL, R. M., & VAN DE CROMMENACKER, J. (2022). Eradication of a highly invasive bird, the common myna acridotheres tristis, facilitates the establishment of insurance populations of island endemic birds. Bird Conservation International, 32(3), 439-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270921000435

- ↑ Messmer, V., Pratchett, M. S., & Clark, T. D. (2013). Capacity for regeneration in crown of thorns starfish, acanthaster planci. Coral Reefs, 32(2), 461-461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-013-1017-1

- ↑ Brodie, J., Fabricius, K., De’ath, G., & Okaji, K. (2005). Are increased nutrient inputs responsible for more outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish? an appraisal of the evidence. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 51(1), 266-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.10.035

- ↑ Arnal, C., Morand, S., & Kulbicki, M. (1999). Patterns of cleaner wrasse density among three regions of the Pacific. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 177, 213-220.

- ↑ Wellings, P. W., Hart, P. J., Kami, V., & Morneau, D. C. (1994). The introduction and establishment of Aphidius colemani Viereck (Hym., Aphidiinae) in Tonga. Journal of Applied Entomology, 118(1‐5), 419-428.

- ↑ Heatwole, H., Busack, S., & Cogger, H. (2005). Geographic variation in sea kraits of the Laticauda colubrina complex (Serpentes: Elapidae: Hydrophiinae: Laticaudini). Herpetological Monographs, 19(1), 1-136.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Viliami M., et al. "Kingdom of Tonga’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Kingdom of Tonga". Mar. 2014

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Smallhorn-West P., and Sheehan, J. "Special Management Area Report 2020" Ministry of Fisheries Kingdom of Tonga, 2020.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2010, March). Forest management - Practices, Tonga. Countries. https://www.fao.org/forestry/country/61585/en/ton/

- ↑ Jupiter, S., Mangubhai, S., & Kingsford R.T. (2014) Conservation of biodiversity in the pacific islands of oceania: Challenges and Opportunities. Pacific Conservation Biology, 20(2), 206-220. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC140206

- ↑ World Meteorological Organization. (2022). State of the Climate in the South-West Pacific (Report No. 1302). https://library.wmo.int/viewer/58225/download?file=1302_Climate_South_West_Pacific_en.pdf&type=pdf&navigator=1

- ↑ Wetzel, F.T., Beissman, H., Penn, D.J., & Jetz, W. (2013). Vulnerability of terrestrial island vertebrates to projected sea level rise. Global Change Biology, 19(7), 2058-2070. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12185

- ↑ Talyor, S., & Kumar, L. (2016). Global Climate Change Impacts on Pacific Islands Terrestrial Biodiversity: A Review. Tropical Conservation Science, 9, 203-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291600900111

- ↑ Roberts CM, McClean CJ, Veron JEN, Hawkins JP, Allen GR, McAllister DE, et al. (2002) Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science (80-);295(5558):1280–4. 10.1126/science.1067728.

- ↑ Friedman, K., Eriksson, H., Tardy, E. and Pakoa, K. (2011), Management of sea cucumber stocks: patterns of vulnerability and recovery of sea cucumber stocks impacted by fishing. Fish and Fisheries, 12: 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00384.x

- ↑ Gillett R. (2017) A review of special management areas in Tonga. Vol. FAO Fisher.

- ↑ Kronen, Mecki. (2004). Fishing for fortunes?: A socio-economic assessment of Tonga's artisanal fisheries. Fisheries Research. 70. 121-134. 10.1016/j.fishres.2004.05.013.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Markic, A., et al. "Microplastic Pollution in the Intertidal and Subtidal Sediments of Vava'u, Tonga." Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 186, 2023, pp. 114451-114451. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X2201133X

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Galloway, T. S., Cole, M., & Lewis, C. (2017). Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(5) doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0116

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Vicedo Ferrer, M. (2021, December 14). Building a Resilient City in the Pacific. https://reliefweb.int/report/tonga/building-resilient-city-pacific

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Takau, Y., & Thompson-Fawcett, M. (2022). Urban planning oscillations: Seeking a tongan way before and after the 2006 riots. Sacred civics (1st ed., pp. 133-145). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003199816-13

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Asian Development Bank. (2022, November 16). Tonga: Nuku’alofa Urban Development Sector Project. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/42394-022-ton-ssa.pdf

- ↑ Spennemann, D. H. R. (2002). Urbanisation in Tonga: Expansion and Contraction of Political Centres in a Tropical Chiefdom. https://www.arkeologi.uu.se/digitalAssets/483/c_483244-l_3-k_spenn.pdf

- ↑ Fall, P.L., Drenzer, T.D., Franklin, J. (2010). Dispersal ecology of the lowland rain forest in the Vava'u island group, Kingdom of Tonga. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 45(2), 393-417. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288250709509722

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Island Conservation. (2023, August 29). Dawn of a New Era: Kingdom of Tonga Undertake Historic Conservation Milestone. Island Conservation. https://www.islandconservation.org/dawn-of-new-era-kingdom-of-tonga-undertakes-historic-conservation-milestone/

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. (2022, December 9). Tonga rat removal project spotlighted at biodiversity COP as an example of restoring island resilience. Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. https://www.sprep.org/news/tonga-rat-removal-project-spotlighted-at-biodiversity-cop-as-an-example-of-restoring-island-resilience

- ↑ Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. (2023, July 7). Tonga rat removal project spotlighted at biodiversity COP as an example of restoring island resilience. Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. https://www.sprep.org/news/tonga-rat-removal-project-spotlighted-at-biodiversity-cop-as-an-example-of-restoring-island-resilience

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 “Tonga Star R2R Project.” R2R, 2023, www.pacific-r2r.org/node/143

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 GEF. “Pacific R2R - Ridge to Reef | SPC-R2R.” Pacific-R2r.Org, 2015, www.pacific-r2r.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/Tonga.pdf.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 GEF. “Implementation of the Fanga’uta Lagoon Stewardship Plan and Replication of Lessons Learned to Priority Areas in Vava’u (Tonga R2R Phase 2).” Global Environment Facility, 2023, www.thegef.org/projects-operations/projects/10518

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Waitt Institute. (n.d.). Tonga | Project Site. Waitt Institute. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.waittinstitute.org/tonga

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Fa’otusia, A., Mafi, A. T., & Veikoso, E. (2019). Plan, engage, coordinate, change: Charting the path ahead for marine spatial planning. Environmental Policy and Law, 48(6), 420-429. https://doi.org/10.3233/EPL-180111

- ↑ Peirano, A., Barsanti, M., Delbono, I., Candigliota, E., Cocito, S., Hokafonu, T., Immordino, F., Moretti, L., & Matoto, A. L. (2023). Baseline assessment of ecological quality index (EQI) of the marine coastal habitats of Tonga archipelago: Application for management of remote regions in the Pacific. Remote Sensing (Basel, Switzerland), 15(4), 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15040909

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Taufa, S. V., Tupou, M., & Malimali, S. (2018). An analysis of property rights in the special management area (SMA) in Tonga. Marine Policy, 95, 267-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.028

- ↑ Stone, K., Menergink, K., Estep, A., Halafihi, T., Malimali, S., & Matoto, L. (2017). Vava’u Ocean Initiative Marine Expedition: Interim Report August 2017. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bxUybMXmyB8R0SX9IBx6rRaaarfQinPT/view

- ↑ Seto, K.; Miller, N.; Young, M.Q. (2022). Toward transparent governance of transboundary fisheries: The case of Pacific tuna transshipment. Mar. Policy. 136.

- ↑ Aranda, M.; de Bruyn, P.; Murua, H. (2010). A report review of the tuna RFMOs: CCSBT, IATTC, IOTC, ICCAT and WCPFC. EU FP7 Proj. 125–171.

- ↑ Vaihola, S., & Kininmonth, S. (2023). Ecosystem Management Policy Implications Based on Tonga Main Tuna Species Catch Data 2002–2018. Diversity, 15(10), 1042. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/d15101042

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 68.4 "Tonga rat removal project spotlighted at biodiversity COP as an example of restoring island resilience. Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme". Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. 2022, December 9. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Writing better articles. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Writing_better_articles [Accessed 18 Jan. 2018].

| This Tropical Ecology Resource was created by Course:GEOS303. |