Course:GEOS303/2022/Philippines (Luzon)

Luzon, Philippines

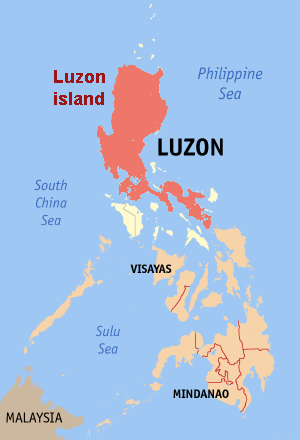

The Philippines is an archipelagic country of 7,641 islands located in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. The country is considered a megadiverse, tropical country due to its biogeographical richness and conditions associated with tropical rainforest biomes. There are three main regions in the Philippines: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. This article focuses on the first and northernmost of the three: Luzon.

| Luzon, Philippines | |

| |

| GEOS 303: Tropical Ecosystems in a Changing World | |

| Continent: | Asia |

| Latitude: | 16.566233 N |

| Longitude: | 121.262634 E |

Biogeography

Dominant Biomes

Luzon, the largest island of the Philippine archipelago, consists of the the Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests (TSMF)[1]. TSMF biomes are characterized by their low annual temperature variability and high rainfall[1]. Semi-evergreen and evergreen deciduous tree species dominate forest composition in the biome[1]. This biotic environment is highly similar to much of Central American and Southeast Asian countries, which are maritime and have high temperatures and precipitation.

A smaller portion of the island falls within the biome classification of Tropical and Subtropical Coniferous Forests[2]. Low precipitation and mild temperature variation are characteristic of this biome[2]. Diverse species of conifers are also frequently found here[2].

Ecoregions and Biophysical Limits

One of Luzon’s ecoregions is the Luzon Rainforests ecoregion, which is within the Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests Biome. Within this ecoregion, there are lowland areas, as well as some lower elevation volcanic mountains. This ecoregion has a temperature that varies between 25 and 28 degrees Celsius, with an annual rainfall of up to 10,000mm[3].

Another ecoregion in Luzon is the Luzon Montane Forests, which is also within the Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests Biome. This ecoregion spans the high elevation mountain ranges, with annual rainfall reaching up to 10,000mm[3].

The final ecoregion within Luzon is the Luzon Tropical Pine Forests ecoregion, situated within the Tropical and Subtropical Coniferous Forests Biome. This ecoregion spans the Central Cordillera Mountain Range where the elevation is above 1000m. The rainfall averages 2,500mm annually, and the average temperature is 20 degrees Celsius. The characteristic species of this ecoregion are the Benguet pine and Saleng tree species[3].

Climatic Limits

Being an archipelagic country near the equator, the climate of the Philippines is described as 'tropical' and 'maritime'[4]. Climate is consistent throughout the entire country, with high temperatures, high humidity, and abundant precipitation and a low seasonality[4]. The mean annual temperature in the Philippines is 26.6ºC, with a mean of 25.5ºC in January and 28.3ºC in May[4]. Climate variation (type I-IV) occurs from west to east of the island, as the western regions generally experience more pronounced wet and dry seasons[4]. A notable exception to this climatic limit is the city, Baguio. Baguio is found at 1,500 m elevation, and records a lower mean annual temperature of 20.6ºC[4].

Many multi-scale systems influence precipitation in the Philippines, including the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), as well as monsoons and cyclones[5]. The summer monsoon season is generated by southwesterly trade winds from the Indian Ocean Anticyclone. Luzon experiences this monsoon season from mid-May to October, and sometimes until November or December[5], amassing an average of 20 typhoons per year.

Biogeographic Limits (Tectonics)

The Philippines is a peculiar and complex area for biogeography. It has been associated both with Asia and Australia in terms of its flora and fauna, and both connections are confirmed through molecular work[6]. However, molecular work also confirms relation to older species[6], which hints at a more complex history.

Most of the Philippines, except for Palawan and western Mindanao is tectonically situated between 2 subducting plates. One is on the east side of the island – the Philippine Trench[7] where the Philippine Sea plate subducts[6]– and another is on the west side – the Manila Trench[7] where the Eurasian plate subducts[6]. This subduction has created the “Philippine Mobile Belt”, which is seismically and volcanically active[6][7]. This generates a unique topography which might also play a large role in Philippine biogeography. This tectonic setting is responsible for the formation of the Philippines, as the subducting plates pulled over continental crust that accreted with other crust pulled from the other subducting plate, generating the archipelago[6].

How flora and fauna came to be on the Philippines, and Luzon in particular, is hotly debated. There is evidence to suggest dispersal from neighbouring islands like Taiwan[7], but other processes have been proposed to explain the high biodiversity. One such theory claims that, as the Philippines were created by the conglomeration of many islands colliding, different species may have arrived in, and contributed to the biodiversity of the Philippines by arriving on these rafts of crust[6]. Another theory, the “Pleistocene Aggregated Island Complex” theory explains that once species arrived in the Philippines in the Pleistocene, cooler temperatures dropped sea levels, and allowed islands to clump together[6][7]. Large “Greater Islands” were present, one of which was Greater Luzon[7]. This theory calls for species to have mingled while the islands were clumped, then to have been isolated when sea level rose, satisfying a vicariant event, although this is also debated[6]. However, other evidence suggests earlier colonizations of Luzon, potentially as far back as Gondwana[7], or other fusing’s of land masses in the Cenozoic era[6] hinting at a more complex history of animal and plant movements requiring more research.

Diversity

Influence of Biogeography and Evolutionary History on Biodiversity

Luzon’s well-known biodiversity has been linked to its geological history. Luzon has never been in contact with other continents, which allows species to be isolated, resulting in a unique center for mammalian biodiversity [8].

Studies have also indicated the role of mountain elevation in facilitating high rates of biodiversity. Maximum species richness of non-volant small mammals tends to be found in mountainous regions with high elevations [8]. The tectonic and volcanic setting of the Philippines, which is responsible for the amalgamation of the island and the processes that generated mountain ranges, provides sufficiently unique topography and elevational gradients to promote speciation in Luzon. Thus, speciation is believed to be the driver of land based small mammal biodiversity on this island, rather than colonization [9].

Endemism

A history of biogeographic isolation has resulted in Luzon Island's high levels of biodiversity and endemism. There are 23 known (small, non-flying) mammals that are endemic to this island[10]. The Central Cordillera highlands, the northern Sierra Madre, the Zambales Mountains, and the Bicol Peninsula have the highest levels of endemism, with the corresponding species richness increasing with elevation[10].

Studies have emphasized high biodiversity in Luzon's different mountain ranges. The Mingan Mountains, for example, is home to at least 35 mammal species, including three that are endemic [11]. Apomys aurorae, Apomys minganensis, and Archboldomys are the species uniquely endemic to the Mingan Mountains [11].

A recent study has also indicated that 52 of the 56 known non-flying mammal species in Luzon are endemic [9]. These non-flying mammal species that are unique to Luzon include different groups of mice such as Musseromys gulantang, Apomys iridensis, and Batomys granti [9].

The Verde Island Passage and the Coral Triangle

The Philippine Archipelago is in the Coral Triangle, one of the worlds centers of biodiversity for marine species[12]. The Coral Triangle hosts over 70% of the world’s known coral species, and over 33% of the world’s reef fish species[12]. The Verde Island Passage, which is a 1.4-million-hectare strait located on the southwest side of Luzon between the island and Mindoro, has at least 1736 shore fish species[12]. Marine ecoregions around the Philippines (in the North and Southeast) are known to have over 500 species recorded[13].

Though the Coral Triangle is evidently very diverse, the reasons behind this diversity are very complex, and therefore not very well understood. Tectonic instability is seen as an agent causing environmental disturbance and habitat complexity, which are thought to promote diversity, and although the Philippines have had a less chaotic geologic past than other areas in the Coral Triangle[13], the interesting tectonic regime mentioned under the “Biogeographic Limits (Tectonics)” subheading above could explain some of this diversity. Pleistocene sea level changes are also thought to have promoted unique shallow water habitats and deep-water habitats, that are also near enough to each other to create a high level of diversity[13]. Yet another potential agent in the formation of this unique biodiversity hotspot are the ocean eddies in the region, that move organisms about and facilitate genetic mixing[13]. These eddies are also temperature and climate dependent, suggesting they change over geologic time, which also helps facilitate the diversity in the area[13].

Human influences

Luzon is greatly known for its high endemism and biodiversity levels. Rising human populations and activities, however, has resulted in many changes that impact the landscape. Such impacts are listed and discussed below.

Traditional Agriculture

Given the presence of tall, steep mountains in the Philippines, Indigenous groups learned techniques to sustainably farm these slopes. In Bayyo, a community known for its rice terraces in the north of Luzon, three traditional methods of farming are practiced by the locals: payew (which are terraced rice paddies), uma (an area characterized by its fallow period), and the katualle system (an unirrigated terrace)[14].

The payew system consists of irrigated terraces usually growing rice and sweet potato[14]. These terraces were harvested constantly and were built along mountainsides and riverbanks[14]. As they are passed down throughout generations, these terraced fields have very much become part of the landscape. Often fertilizers are used in the terraces, like sunflower stems and other foliage[14], however other groups have been known to use animal waste products or fermented plant material[15].

The katualle system is similar to the payew, however it is unirrigated[14]. These terraces are also fertilized with surrounding dead plant material and animal waste[14]. Most newly collected crops are grown in the katualle, making them function as a kind of nursery for seeds[14]. With increasing modernization and globalization of crops, the katualle are also where newer varieties of existing crops, as well as non-native crops like tobacco and coffee are produced[14].

The uma is the only production system of the three that does not call for terraces. Rather than building anthropogenic structures on the land for farming, the uma calls for clearing upland mountainous areas of forest or bush, and preparing them for cultivation[14]. Farmers select for sites absent of many stones, and with large trees, then proceed to cut and burn the areas to remove all prior vegetation[14]. Uma fields are used for a short time, perhaps up to 5 years, then are left to regenerate for up to 20 years[14]. This traditional style of slash and burn agriculture is another way humans have influenced the environments in the Philippines for countless years.

Logging Practices

Forests in Luzon have been a source of timber for humans and have experienced unsustainable logging practices. During the 1970s to 1990s, the country’s rainforests reduced from about 70% to less than 10% [16]. The ongoing deforestation to support human activities have resulted in various implications such as soil erosion, biodiversity loss, watershed degradation, and floods [16].

Specifically, logging operations in the 1950s attracted many workers to settle in Northeast Luzon [17]. These settlers developed farmland in previously forested areas and increased demand for fish and game [17]. Furthermore, unsustainable logging techniques degraded the forest's crucial function to regulate water [17]. The forest lost its capacity to absorb water due to severely eroded riverbanks, obstructed waterways, and deforested slopes [17]. As a result, more flash floods and mudslides occurred [17].

Mining and Dams

Mining in Northern Luzon is deeply tied to colonial roots. Corporate mining began with Spanish colonization in the 1500s along the gold rich rivers of the Benguet region in Northern Luzon and was revamped with American colonization in the 1900s[18]. Since the advent of corporate mining, 3 dams have been constructed on the Agno River, and 12 other dams have been constructed throughout Benguet[18].

After closures of mines in 1997, new applications for mines in Benguet increased; ones that would cover over 50% of the province’s total area, excluding the past and present mines in the area[18]. Tailings dams were also constructed along with the mines and have collapsed on many occasions: Breaches in 1992, two breaches in 1994, and a breach in 2001 all exemplify how mining operations have released toxic waste into the Abra, Agno, Antamok, and Bued Rivers of this province, severely polluting both the soil and the water[18]. This polluted water is thought to be responsible for ever increasing fish kill downstream of the tailings dams, as well as the vanishing of once prevalent birds and trees[18].

The major mining corporations are known to practice open-pit mining, which destroys soil and vegetation, clearing forests and causing streams to be diverted, which inevitably leads to water loss[18]. These open pit mines further cause the land to sink and subside, as well as draw down the water tables, which has had major impacts on the irrigation abilities of Indigenous villages[18].

These problems have continued to plague the Philippines, as even after the Environment Secretary ordered countless mines to shut down in 2017 for their detriment to the environment, these mines have continued to operate[19].

Species Introduction

Humans have also shaped the ecology of the island through their trading and animal management practices. Various species such as domestic pigs and dogs, as well as bovines were brought to the island from mainland Asia around 2000-400 BC ago[20]. While most of these species are domesticated, their introduction have affected the islands biodiversity as they have interacted with various endemic species. It is also noted though that populations then still relied heavily on hunting of various species on the island for food, and these practices continue to this day[21].

Threats

Habitat Loss & Fragmentation

As forest cover has declined significantly in the Philippines (from 70% to 7%), habitat loss presents as a great risk to biodiversity[22][21]. Specifically, deforestation and forest disturbances result in lower species diversity and abundance, transformations on species assemblages, loss of guilds, and extinction [21]. One such study focused on habitat loss surveyed areas in Northern Luzon that have been disturbed by human processes like agriculture and logging, and quantified how native and non-native small mammal species react to habitat loss[22]. The authors found that as habitat loss increased, species richness decreased, noting that native species were found in lightly to moderately disturbed areas, and that non-native species were found in severely degraded habitats[22]. They also discovered that native species eventually do reoccupy and outcompete non-native species in habitat that is regenerating[22]. Considering the major habitat loss in the Philippines, native small mammal species are threatened more so than non-natives [22], which would eventually result in a shift in species composition and a loss in biodiversity. However, given that the native species in this study were able to reoccupy regenerating habitat, and that they were found in high numbers in moderately disturbed habitats [22], there appears to be potential for small mammal species to continue existing, should disturbance not accelerate, and habitat be left to regenerate.

Another study of forests in Subic Bay, Luzon highlights the negative impacts of anthropogenic land use on birds and butterflies [21]. The study shows that while some species are able to persist in urbanized environments, the majority of them experience detrimental impacts [21]; the lowest number of forest species were found in urbanized environments compared to other land types [21]. This impact on biodiversity is crucial as it hinders the ability for ecosystems to be resilient in changing environments [23]. In fact, the need for resilient systems is increasing as climate change impacts continue to worsen. With rising human populations, and the ever increasing demands for natural resources, whether maintaining moderate disturbance is realistic will remain to be seen.

Case Study: Philippine eagle

The Philippine eagle is one of the world's most endangered birds of prey, with less than 900 adults remaining between the four islands it is found in: Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao[24]. The Philippine eagle, also known as the Haribon, is impacted significantly by habitat loss through deforestation. This is mostly due to illegal logging and an exploitation of resources[24]. The Haribon's distribution in Luzon has shifted to the eastern half of the island, and specifically to the Sierra Madre Mountains, where wildlife is still threatened by forest loss and human threats[24]. This shifted range of the Haribon often brings these eagles away from their usual territory and into contact with human settlements, where conflict leads to shooting of an eagle at least once a year[24]. As endemic, tertiary predators, the loss of their population threatens the biodiversity of Luzon's ecosystems and its unique biological heritage[24].

In addition to the Philippine eagle, deforestation in Luzon has impacted more than a dozen species of birds to a "near-threatened" status[25]. Habitat loss has a major impact on Luzon's endemic species, as there are no alternative native habitats for these species[25]. It will be crucial to preserve the habitats of these native species which heavily contribute to global biodiversity in a relatively small geographical range.

Invasive Species

The introduction of an invasive species can result in significant changes in species diversity, abundance, and energy flow [26]. Such changes displace native species, diminishes diversity, and disrupts ecosystem functioning [26]. In the Philippines, there are many cases in which invasive species threaten native species and, thus, overall biodiversity [26]. For instance, Arctodiaptomus dorsalis was introduced in Luzon through ship drinking water reserves and is now found in 18 out of 27 lakes in the Philippines [27]. Research findings suggest that this introduction has displaced native and endemic calanoids, resulting in the loss of calanoid diversity in the Philippines [27]. Furthermore, a study in Luzon has found that a non-native rodent species, Rattus tanezumi, had devastating implications for agroforest ecosystems and native fauna [28]. Agroforests with the invasive rodent present experienced sustained habitat disturbance [28]. In addition, rapid recolonization of native rodent species occurred when R. tanezumi were removed in systems [28].

Hunting Wildlife

Hunting wildlife has been an essential food source for Indigenous peoples for thousands of years, and can serve as a source of income and relatively inexpensive food for regions [29]. This demand for hunting, however, must be weighed against hunting impacts on biodiversity. In Luzon, wildlife hunting practices target various species and are suspected to be widespread [29]. A wide number of organisms are hunted, large to medium mammals like the Philippine warty pig or Philippine brown deer are favoured for their protein rich meat, and deer horns are also burned and the ashes used to cure skin diseases[21]. Bats like the Large flying fox and other medium sized fruit bats are also hunted, along with monitor lizards and snakes. Finally large birds like the Hornbill or fruit doves are eaten[21]. The Great Philippine Eagle, however, is not touched due to its endangered status and importance to the country, being its national bird. All of these organisms are hunted for food but also sometimes are hunted to protect farmers crops and livestock, as a warty pig may uproot young seedlings or a monitor lizard may attack livestock[21]. Traditional medicines also require body parts too, like the deer horns, or snake bile which is dried and ingested to cure stomach issues.

It is crucial to note such practices as most of the targeted species are globally near-threatened and significantly contribute to ecosystem functioning [29]. For instance, the giant flying fox and white-winged flying fox that are endemic to the Philippines are highly endangered and declining in numbers due to overhunting [29]. Possibly due to the development and spread of gun usage, hunting flying foxes has become unsustainable [30]. This species is important as it significantly contributes to forest regeneration through seed dispersal and pollination [29][30]. Declines in their numbers pose implications for plant communities [29], which can further result in cascading effects.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture, being the most rapidly growing global food sector, has led to drastic changes and impacts on the environment. In the past, the population of Bulacan, Central Luzon relied primarily on fishing aquatic organisms in water systems such as Manila Bay, and commonly utilized rice farms [31]. In the 1990s, however, many rice farms were converted to fish ponds because aquaculture increased in profitability and salinity levels grew which impacted the ability to produce rice [31].

Currently, aquaculture production in Central Luzon is diverse, including methods such as small fish caging, intensive large fish pens, and semi-intensive brackish water fish ponds [31]. Many households depend on capture fisheries for a source of income and food, and fish production is mainly driven by aquaculture [31]. Aquaculture and the fishery industry, however, have resulted in increased water pollution levels which have raised the frequency of fish kills in ponds and disappearance of local aquatic organisms [31]. They have also resulted in decreasing levels of biodiversity. For instance, intense mussel farming in Luzon has been held responsible for the decline in species richness and diversity of dinoflagellate cysts [32]. This decline occurs as mussel farming processes facilitate eutrophication [32], where harmful algae blooms develop and limit the oxygen available for organisms.

Human Management Practices

Protected areas were setup in the Philippines in the 1930s during the period of American occupation[33], they followed a similar model to ones seen in America where a section of land was taken and most human activities on it were banned, so attempting to create a 'natural' area for species to live away from human influences. While they sound like a good idea these parks had no management systems until the 1980s and were referred to as 'paper parks' [33]. In the 1980s the Department of Environment and Natural Resources setup the Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau to manage the parks, and in 1992 the National Integrated Protected Areas System law was passed which officially encompassed 203 protected areas in the country[33]. All of this sounds positive however the failure to manage these parks and lack of resources have meant these protected areas often fail to complete their goal of protecting biodiversity. The locations of parks is also a problem, as many biodiversity hotspots are not protected while less active areas are, for example only 36% of endemic bird areas are protected and none have over half their area actually protected[33]. The management of sites is also a problem and many biodiversity hotspots do not have the necessary resources to adequately manage their biodiversity. About 40% of the now 240 protected areas have no outline management plan[33], and only 15% have a revised or final plan that is based off research and data collection of the area[33]. Other protected areas have no permanent staff, let alone an onsite biologist, meaning many collect data however have no one who can analyse or make decisions based off it[33]. Some progress has been made on this, especially through the NewCAPP project, However, a large portion of protected areas still lack the resources, authority and management capabilities to effectively manage and preserve the biodiversity they are meant to protect, and if no changes are made this mismanagement poses a serious threat to future biodiversity.

Conservation

1) Reforestation: The National Greening Program

Deforestation in the Philippines has been a major problem for decades. Between 1970 and 1990, Philippine rainforests were degraded to less than 10% of what they had been[34]; around 10.9 million hectares[35]. To combat this drastic loss, the Philippines have embarked on the National Greening Program (NGP), whereby over a billion seedlings are meant to be planted[34]. The NGP is meant to amend exploitative processes and help boost the economy[34], as well as contribute to reducing poverty, promote sustainable management of natural resources, mitigate climate change, and improve ecosystem services more broadly[36]. The program was started in 2011, and was set to end in 2016, however the over 4 million jobs created by the program, of which over 500,000 individuals were hired as workers, has encouraged the creation of the Expanded NGP (ENGP), which aims to rehabilitate the remaining 7.1 million hectares of degraded forests[34][35]. Part of this social success of the program stems from providing poorer farmers with the opportunity to do the tree planting, while also reaping the benefits of the economically valuable trees like rubber and fruit[34].

- Studies have been done to evaluate the success of the NGP, especially in Northern Luzon in forests like the Sierra Madre, where much of the surviving old-growth forests in the country are located, as well as in the Cordillera forest[34]. Unfortunately, losses in forest cover were consistent in Luzon throughout the time the NGP was active, and further, forest or vegetation increase has been almost non-existent[34]. Deforestation was occurring during the NGP program, and many seedlings were planted in areas not conducive to their survival[34].

Thus, though the program seemed to be a major success in terms of the social and economic benefits to the people, the actual conservation value of the NGP was negligible.

2) The CROC Project

The Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) is endemic to Luzon and a critically endangered species, as indicated by the IUCN. Due to activities such as hunting, unsustainable fishing, and habitat loss, the species has become the most threatened crocodile species on the planet [37]. The Philippine crocodile was believed to be extinct in Luzon, but a rediscovery of the species in Northern Sierra Madre sparked the initiation of a conservation project: the Crocodile Rehabilitation, Observance and Conservation (CROC) project [37]. The CROC project, which was initiated in 2002, aims to conserve and rehabilitate the remaining C. mindorensis populations found in Northeast Luzon [37]. To reach its goals, the CROC project has implemented various strategies to conserve the crocodile populations. These strategies and their outcomes are described as follows:

- Obtaining and Providing accurate data on the species:

- The project has obtained ecological information about the species through population surveys, quarterly monitoring of the population in three breeding areas, catching, and radio tagging [37]. Relevant socio-economic data was also obtained, such as information on existing threats to the species, level of public awareness, and the impact of crocodile conservation on local communities [37]. Such surveys and monitoring initiatives have been successful as they provide relevant information for evaluating and changing the project’s conservation strategies. For instance, the population surveys found that the crocodile species was also present on Dalupiri Island, leading the CROC team to include this region in their monitoring program [38]. The data on driving threats also found that coastal sites experienced illegal fishing activities [38]. This finding influenced various activities to be implemented in the coastal sites, such as the development and distribution of various educational materials (posters, calendars, and newsletters), as well as the the organization of a summer course to obtain information about the area [38].

- Communication Education and Public Awareness (CEPA) Campaign

- The CEPA campaign was developed to increase the knowledge and awareness of local community members about crocodiles [37]. The campaign includes developing visitors centers, conducting school visits and presentations, as well as developing educational materials [37]. These initiatives have been very successful in engaging and informing students. Many institutions have been visited, ranging from elementary to high schools, and over 400 students have been reached during school visits [38]. Such activities have not only increased the knowledge of local youth, but they have also helped raise support for other conservation initiatives conducted by the CROC team.

- Crocodile Protection

- The project also aims to create crocodile reserves and other protection measures [37]. After two years of implementation, forty-six non-hatchling crocodiles survived in the wild which is an additional sixteen nonhatchling crocodiles since 2005 [38]. To develop these conservation plans, project members have consulted with community members to discuss the project’s goals and aims [37]. Further, the project has collaborated with the DENR, the mandated agency that conserves wildlife and enforces regulations, to enhance their understanding and commitment to crocodile conservation. Together, they have implemented a wildlife enforcement training to inform officer’s about the Wildlife Act [38]. However, these initiatives were not very successful as certain officials in the DENR were found to be involved with illegal logging activities [38]. As a result, the CROC team made an effort to establish local protection groups (also known as Bantay Sunktuwaryo) to monitor the sanctuaries and implement community-based rules/regulations [37]. This approach has resulted in more local action to conserve the species [38].

- Cooperation and engagement of stakeholders

- To develop long-term efforts for conservation, the project aimed to enhance collaboration between local stakeholders and develop a regional center of expertise. Specifically, It has developed a local foundation, known as the Mabuwaya Foundation, which has helped secure funding [37]. The project has also held several workshops to train the local members on sustainable management [37]. The foundation has enabled engagement within the local community. For example, it conducted a 2-week summer class in Divilacan, and 20 students from CFEM and the College of Engineering participated in it [38]. The class offered hands on job training which enabled several students to assist conservation organizations in the area [38]. The organization also invests in various partnerships within and outside the conservation region. It works closely with local organizations such as the Northern Sierra Madre Wilderness Foundation (NSMWF) to share information about the species and provide monitoring training [38].

3) The NewCAPP Project

The NewCAPP or New Conservation Areas in the Philippines Project ran from 2010 to 2015, and was aimed at improving the protected area system in place in the country[39], it was a nationwide project which covered every island of the country, including Luzon. The project had three main outcomes; to expand the protected area system to cover an additional 400,000 hectares, to improve conservation effectiveness through enhanced systemic, institutional and individual capabilities, and to enhance the financial sustainability of the protected area system[39]. The project was decided upon due to the ever decreasing biodiversity seen in the country, and while it had protected areas covering 13.5% of total land area in 2010[33], these areas were poorly managed, poorly situated or both, and hence were ineffective in their task. As such the project aimed to vastly improve and increase the effectiveness of these areas following the three main outcomes above as a guideline for what factors needed to be worked on.

Due to the size of the project many levels of organisation worked together to achieve its goals, from the national level down to local communities. This was seen to be beneficial in some areas where increased cooperation was seen between the required partnership arrangements, while in others it led to disruptions. It was co-funded too, with GEF and UNDP funding, as well as the national government, NGOs and local communities contributing[39].

In regards to achieving its desired outcomes the project was largely successful and can be viewed as a win for conservation in the country. Forty six new protected areas were added to the system, and an increase in key biodiversity area coverage was seen along with a 200% increase in coverage for 109 globally threatened species (coverage was expected to drop 10% per year)[39]. Additionally, clear weaknesses of the protected area system were identified and were then improved to make the system more effective and managing itself. Awareness of the protected areas was also raised in the Philippines and as such they are taken more seriously. Further achievements are that tools and mechanisms to sustainably fund the areas were thought of and introduced, all earnings the areas make now return 100% to them as well, substantially increasing the financial resources of protected areas[39].

A key part of this project revolved around the inclusion of local communities and indigenous peoples of the country. A number of the new protected areas are designated as LCAs or ICCAs, Local Conservation Areas and Indigenous Community Conserved Areas respectively. The management of these areas falls to the local communities and they are taught how to map and inventory their lands, as well as other methods to help biodiversity[40]. Certainly for indigenous peoples this has an added benefit of allowing them to protect their traditional lands, and thus their traditional ways of life. Unfortunately the economic benefits the NewCAPP project said would effect these local communities had not appeared by the end of the project[39].

4) The Philippine Eagle Conservation Efforts

There are many conservation organizations that are working towards the conservation and protection of the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi ). The Philippine eagle is endemic to the Philippines and is both culturally and ecologically important to the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao[41]. The Philippine Eagle has been on the IUCN’s Red List as a Critically Endangered (CR) species since 1994, and was previously on the IUCN’s Threatened (T) list in 1988. The island of Mindanao has an estimated 82-233 breeding pairs, while only one has been observed in Luzon in 2015[41]. However, the population trend is decreasing, meaning that these numbers could be currently be lower. Forest fragmentation and degradation as well as hunting are the primary threats to the Philippine eagle.

A Protected Species

The Philippine Eagle appears in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), meaning that it is highly threatened. Species in Appendix I of CITES are protected against international trade[42]. Furthermore, the Philippine Eagle’s range falls within the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park in Luzon, which is the largest protected area in the Philippines[43]. The Philippine Eagle is also flagship species for biodiversity and conservation[44]. The fact that the eagle has become so well-known has helped fund conservation efforts, which has led to some success towards protecting this species.

Haribon Foundation

The Haribon Foundation aims to study, understand, and share knowledge about the Philippine Eagle to protect and conserve the species. The Philippine Eagle Project was started by the Haribon Foundation, and ran from 2014 to 2017. This project started with biophysical surveys and focus group discussions within communities to come up with a Critical Habitat Management Plan (CHMP), as well as the Forest Protection and Law Enforcement Plans (FLEPS)[45]. This project was successful in providing training to 76 Bantay Gubat Wildlife Enforcement Officers, and provide education about the Philippine Eagle and the importance of biodiversity to 800 students. It was also successful in establishing Forest Protection plans, however, it is unclear whether it has helped the Philippine Eagle population.

Philippine Eagle Foundation

The Philippine Eagle Foundation works towards culture-based conservation, collaborating with Indigenous peoples and communities to conserve the species[46]. Indigenous cultures, knowledge, and traditions are seen as being integral to conservation efforts, and the Philippine Eagle Foundation aims to conserve the Philippine eagle while strengthening Indigenous communities. Over 60% of the Philippine eagle's habitat is in Indigenous territories, which is what made this collaboration so important[46].

The Philippine Eagle Foundation also has a Rescue, Rehabilitation, and Release Program. Local Government Units partner with the Philippine Eagle Foundation to find and capture injured eagles. These eagles are then treated by veterinarians and biologists, and released back into the wild with a GPS tracker[47].

The Philippine Eagle Foundation also does forest surveys, as well as visit local communities to educate and spread knowledge about the species[47].

Conservation breeding is done at the Philippine Eagle Foundation, using “natural pairing techniques” as well as “cooperative artificial insemination’. Since 1992, this technique has led to the success of 28 eagles[48].

The Philippine Eagle Foundation has had success in spreading awareness, building relationships with local Indigenous communities, and releasing a number of Philippine Eagles into the wild. The Philippine eagle is a difficult species to protect as its population is so small, however, this organization has made some success.

5) Verde Island Passage Protection

Off the southwestern coast of the main island of Luzon lies one of the most productive, biodiverse ecosystems in the world. Verde is a small, 17.37 sq. km island found between Batangas and Mindoro Island, which are all found in Luzon[49]. Although the island population is only 5,075, the productivity of the 100 km-long marine passage sustains the livelihoods of 7 million people[49][50]. Composed of mangrove forests, diverse coral reefs, and meadows of seagrass, the Verde Island Passage supports at least 1736 shore fish species[49][50]. The marine passage is found in the "Coral Triangle", and is considered the "centre of the centre" of marine biodiversity[49].

Over the years, numerous local threats have arose in the Verde Island Passage. Overfishing has put tremendous pressure on the local fish populations, with groupers, snappers, and tuna being popular catches and therefore highly threatened[49]. Additionally, many fishing practices have also been illegal and destructive to more marine habitats[49]. Techniques including blast fishing and cyanide fishing have not only racked a high by-catch (including sea turtles, manta rays, and dolphins), but also destructed the coral reefs that are locally and globally significant[49]. Overfishing and habitat degradation, as well as coastal erosion, greatly threaten the biodiversity and productivity of this ecosystem. Food availability, livelihood, tourism, and water quality have all been impacted by these events[49].

Conservation of the Passage

In response to the issues, many conservation efforts have been directed towards the Verde Island Passage. Global and regional policies have led to the establishment of 2000 marine protected area sites (MPA) throughout the Verde Island Passage[51]. These MPAs are either fully protected from any extraction, or protected from over-harvesting[50]. Conservation International Philippines reported a collective increase of over 16,000 hectares of MPAs, and the revival of coral reefs and mangrove forests[52]. These are yielding many ecological as well as socioeconomic benefits for Luzon. Fisheries are starting to recover, maintaining biodiversity while providing a stable food supply and source of income[51]. The water quality of the Verde Island Passage is also improving, which safeguards the coastal shorelines from erosion and degradation[51]. The joined conservation efforts have also met the needs of livelihood and tourism, providing economic benefit to less economically active provinces such as Batangas and Mindoro[51].

Despite the great efforts towards protecting this passage, there are still imperfections with conservation of the Verde Island Passage. MPAs are a buffer but still face the effects of environmental perturbations, and inertia effects from the harmful extracting processes[51]. However, establishing many MPA sites and networks have the potential to engage local communities as well as large stakeholders in the efforts of conservation[51]. Studies show evidence that implementing the Integrated Coastal Management (ICM) program (adapted from the UN Conference on Environment and Development 1992) can contribute to a highly sustainable MPA network[53]. And as international organizations and local stakeholders continue to invest into these efforts and evolve, the fruits of this conservation can only grow.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forest Ecoregions". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Tropical and Suptropical Coniferous Forest Ecoregions". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sawe, Benjamin Elisha (April 25 2017). "Ecological Regions of the Philippines". Retrieved October 5 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Climate of the Philippines". PAGASA - GOVPH. Retrieved Oct 6 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Olaguera, Lyndon (2021). "A climatological analysis of the monsoon break following the summer monsoon onset over Luzon Island, Philippines". International Journal of Climatology. 41: 2100–2117 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 Heads, Michael (2013). Biogeography of Australasia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 356–362.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Vallejo, Benjamin (2014). Biodiversity, Biogeography and Nature Conservation in Wallacea and New Guinea. Volume II. Latvian Society of Entomology. pp. 47–55.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Balete, D. S., Heaney, L. R., Veluz, M. J., & Rickart E. A. (2008). Diversity patterns of small mammals in the zambales mts., luzon, philippines. Elsevier. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1016/j.mambio.2008.05.006.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Heaney, Lawrence & Balete, Danilo & Duya, Mariano Roy & Duya, Melizar & Jansa, Sharon & Steppan, Scott & Rickart, Eric. (2016). Doubling diversity: A cautionary tale of previously unsuspected mammalian diversity on a tropical oceanic island. Frontiers of Biogeography. 8. 10.21425/F58229667.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rickart, Eric A.; Heaney, Lawrence R.; Tabaranza, Blas R. (January 23 2010). "Small mammal diversity along an elevational gradient in northern Luzon, Philippines". Mamalian Biology. 76(1): 12–21 – via Elsevier Science Direct. Unknown parameter

|Last Name 3=ignored (help);|first3=missing|last3=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Balete, D. S., Alviola, P. A., Duya, M. R. M., Duya, M. V., Heaney, L. R., & Rickart, E. A. (2011). Chapter 3: The mammals of the mingan mountains, luzon: Evidence for a new center of mammalian endemism. Fieldiana. Life and Earth Sciences, 2011(2), 75-87. https://doi.org/10.3158/2158-5520-2.1.75

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Servonnat, M., Kaye, R., Siringan, F.P., Munar, J., Yap, H.T., 2019. Imperatives for Conservation in a Threatened Center of Biodiversity. Coastal Management 47, 453–472.. doi:10.1080/08920753.2019.1641040

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Veron, J.E.N., Devantier, L.M., Turak, E., Green, A.L., Kininmonth, S., Stafford-Smith, M., Peterson, N., 2009. Delineating the Coral Triangle. Galaxea, Journal of Coral Reef Studies 11, 91–100.. doi:10.3755/galaxea.11.91

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 Magcale-Macandog, D., Ocampo, L.J.M., 2005. Indigenous Strategies of Sustainable Farming Systems in the Highlands of Northern Philippines. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 26, 117–138.. doi:10.1300/j064v26n02_09

- ↑ Villegas-Pangga, Gina. (2013). Improvement of Soil Health and Soil Quality through Indigenous and Restorative Organic Farming Technologies. National Research Council of the Philippines Research Journal. 13.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Perez, G. J., Comiso, J. C., Aragones, L. V., Merida, H. C., & Ong, P. S. (2020). Reforestation and deforestation in northern luzon, philippines: Critical issues as observed from space. Forests, 11(10), 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11101071

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Persoon, G. A., & Minter, T. (2020). Knowledge and practices of indigenous peoples in the context of resource management in relation to climate change in southeast asia. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 12(19), 7983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197983

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 Cordillera Peoples Alliance, Case Study on the Impacts of Mining and Dams on the Environment and Indigenous Peoples in Benguet, Cordillera, Philippines, Presented at United Nations International Expert Group Meeting on Indigenous Peoples and Protection of the Environment in August 27-29, 2007. pp. 2-11. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/workshop_IPPE_cpp.doc

- ↑ Catajan, M. E. (2021, January 31). Philippine mines continue unhampered 4 years after Gina's shutdown order. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Retrieved November 17, 2022, from https://pcij.org/article/4465/philippine-mines-continue-unhampered-4-years-after-ginas-shutdown-order

- ↑ Amano, N (2013). "Introduced Domestic Animals in the Neolithic and Metal Age of the Philippines: Evidence From Nagsabaran, Northern Luzon". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 8: 317–335.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Tanalgo, K. C. (2017). "Wildlife hunting by indigenous people in a Philippine protected area: A perspective from Mt. Apo National Park, Mindanao Island". https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.2967.9.6.10307-10313. 9(6). External link in

|journal=(help) Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name ":17" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Rickart, E. A., Balete, D. S., Rowe, R. J., & Heaney, L. R. (2011). Mammals of the northern Philippines: Tolerance for habitat disturbance and resistance to invasive species in an endemic insular fauna. Diversity and Distributions, 17(3), 530–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2011.00758.x

- ↑ Gevaña, D.T., Villanueva, C.M.M., Garcia, J.E., Camacho, L.D. (2022). Mangroves Sustaining Biodiversity, Local Livelihoods, Blue Carbon, and Local Resilience in Verde Island Passage in Luzon, Philippines. In: Das, S.C., Pullaiah, Ashton, E.C. (eds) Mangroves: Biodiversity, Livelihoods and Conservation . Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0519-3_17

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 "The Philippine Eagle | PEF". 2019.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Poulsen, Michael Køie. "The threatened and near-threatened birds of Luzon, Philippines, and the role of the Sierra Madre mountains in their conservation". Bird Conservation International. 5 (01): 79–115 – via Research Gate.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hubilla, M., Kis, F., & Primavera, J. (2007). Janitor fish Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus in the Agusan Marsh: A threat to freshwater biodiversity. Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 10(1), 10-23. http://hdl.handle.net/10862/3519

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Papa, R. D. S., Li, H., Tordesillas, D. T., Han, B., & Dumont, H. J. (2012). Massive invasion of arctodiaptomus dorsalis (copepoda, calanoida, diaptomidae) in philippine lakes: A threat to asian zooplankton biodiversity? Biological Invasions, 14(12), 2471-2478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0250-9

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Stuart, A. M., Prescott, C. V., & Singleton, G. R. (2016). Can a native rodent species limit the invasive potential of a non‐native rodent species in tropical agroforest habitats? Pest Management Science, 72(6), 1168-1177. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.4095

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Scheffers, B. R., Corlett, R. T., Diesmos, A., & Laurance, W. F. (2012). Local demand drives a bushmeat industry in a philippine forest preserve. Tropical Conservation Science, 5(2), 133-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291200500203

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Van Weerd, M., Guerrero, J. P., Tarun, B. A., & Rodriguez, D. (2003). Flying foxes of the northern sierra madre natural park, northeast luzon. CVPED and Golden Press.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Manlosa, A.O., Hornidge, AK. & Schlüter, A. Institutions and institutional changes: aquatic food production in Central Luzon, Philippines. Reg Environ Change 21, 127 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-021-01853-4

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Baula, I. U., Azanza, R. V., Fukuyo, Y., & Siringan, F. P. (2011). Dinoflagellate cyst composition, abundance and horizontal distribution in bolinao, pangasinan, northern philippines. Harmful Algae, 11, 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2011.07.002

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 Mallari, Neil (2016). "Philippine protected areas are not meeting the biodiversity coverage and management effectiveness requirements of Aichi Target 11". Ambio. 45(3): 313–322.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 34.6 34.7 Perez, G.J., Comiso, J.C., Aragones, L.V., Merida, H.C., Ong, P.S., 2020. Reforestation and Deforestation in Northern Luzon, Philippines: Critical Issues as Observed from Space. Forests 11, 1071.. doi:10.3390/f11101071

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Ahmed, H. (2018, October 9). Pockets of success in the Philippines' National Greening Program. Pockets of Success in the Philippines' National Greening Program | NBSAP Forum. Retrieved November 24, 2022, from https://nbsapforum.net/knowledge-base/best-practice/pockets-success-philippines%E2%80%99-national-greening-program

- ↑ Department of Environment and Natural Resources, R. of the P. (2019, May 27). Enhanced National Greening Program. Retrieved November 24, 2022, from https://www.denr.gov.ph/index.php/priority-programs/national-greening-program

- ↑ 37.00 37.01 37.02 37.03 37.04 37.05 37.06 37.07 37.08 37.09 37.10 37.11 The Mabuwaya Foundation Inc. (2005). Crocodile Rehabilitation, Observance and Conservation (CROC) project. https://www.conservationleadershipprogramme.org/media/2014/11/001203F_Philippines_FR_CROC_Project.pdf

- ↑ 38.00 38.01 38.02 38.03 38.04 38.05 38.06 38.07 38.08 38.09 38.10 The Mabuwaya Foundation Inc. (2008). Crocodile Rehabilitation, Observance and Conservation (CROC) project: the conservation of the critically endangered Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) in Northeast Luzon, the Philippines. https://www.conservationleadershipprogramme.org/media/2014/11/2005_-Philippines_CROC-consolidation-award-final-report.pdf

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 Onestini, Maria (February 2016). "Report for the Terminal Evaluation of the Expanding and Diversifying the National System of Terrestrial Protected Areas in the Philippines Project (NEWCAPP)" (PDF).

- ↑ Eleazar, Floradema (January 2016). "Establishing Indigenous Community Conserved Areas in the Philippines". Panorama.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Ibanez, J (2018). "Pithecophaga jefferyi (amended version of 2017 assessment)". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. e.T22696012A129595746.

- ↑ "Appendices". CITES. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ "Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park".

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ "Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi". Retrieved December 2, 2022.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ "The Philippine Eagle Project". March 20, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Culture-Based Conservation". 2019.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ 47.0 47.1 "What We Do". Retrieved December 2, 2022.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ "Conservation Breeding". Retrieved December 2, 2022.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 49.5 49.6 49.7 R. Boquiren, G. Di Carlo, and M.C. Quibilan. 2010. Adapting to Climate Change. Maintaining Ecosystem Services for Human Well-being in the Verde Island Passage, Philippines. Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Servonnat, Marine (2019). "Imperatives for Conservation in a Threatened Center of Biodiversity". Coastal Management. 47, No. 5: 453–472 – via Taylor & Francis Group.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 Chua (2018). Local Contributions to Global Sustainable Agenda: Case Studies in Integrated Coastal Management in the East Asian Seas Region. pp. 503–513.

- ↑ "Protecting the Natural Riches of the Verde Island Passage".

- ↑ "ICM Principles".

| This Tropical Ecology Resource was created by Course:GEOS303. |