Course:GEOS303/2022/Colombia

Colombia is one of the vastly diverse countries that make up Earths tropical ecosystems. Colombia is located in South America, and is the only country in the continent to border both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It shares its national borders with Brazil, Ecuador, Panama, Peru and Venezuela. Colombia became a country in 1819 when it declared its independence from Spain. It wasn’t until 1822 when the United States officially recognized Colombia by acquiring a Colombian diplomat[1].

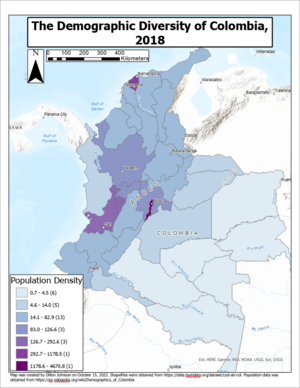

Currently, over 51 million people call Colombia home. Bogotá is the capital city with over 7.1 million residents[2]. Roughly 86% of the population in Colombia is of Mestizo heritage[3]. Mestizo is the name given to people of combined Indigenous American and European ancestry.

Colombia is known for its high species richness and diversity. The country is teeming with wildlife.

Biogeography

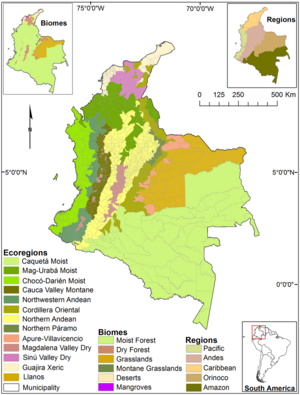

Colombia's most recent official regionalization delineates six main biogeographic regions according to the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC), Colombia's official source for regional cartography: Andean, Pacific, Caribbean, Orinoquía, Amazon, and Insular.

These six regions are further divided into 50 sub-regions.

Andean region

The Andean region, a mountainous zone situated in central Colombia, is home to more than sixty percent of the country's human population, containing the majority of its dense urban centres including Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali. It is composed of fifteen departments including Nariño, Chocó, and Valle del Cauca.[4]

Its biogeographic subregions include the West Andes (Cordillera Occidental), East Andes (Cordillera Oriental), Central Andes (Cordillera Central), Colombian Massif, Cauca River Valley, Magdalena River Valley, and the Massif of Huaca (Nudo de los Pastos). It also contains more than twenty national parks.

The Andean natural region is Colombia's most botanically diverse, containing 11,500 different plant species within its boundaries. It falls behind many of the other natural regions in some measurements of biodiversity, especially in its number of different aquatic bird and fish species.[5]

Pacific region

The Pacific region comprises all of Colombia's western coast, bordering Panamá and the Darién Gap to the north, and Ecuador to the south. It shares nearly all of its eastern border with the West Andes and contains four of Colombia's departments. This region is a biodiversity hotspot made up of thick rainforest, swamps, and mangroves and sees little topographic variation. It hosts several national parks including Los Katíos, Utría, Sanquianga, and Uramba Bahía Málaga.[6]

This ecoregion shares much of its area with the Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena biodiversity hotspot, spanning from northwestern Peru at its southernmost end to Panamá at its northernmost. The Pacific coastal lands of Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena are extremely species rich, with more than 2750 endemic plant species within their borders and experiencing some of the highest precipitation levels in the world.[7]

Caribbean region

Colombia is one of the only South American countries with a Caribbean coastline. Comprising nearly all of Colombia's northernmost shores, the Caribbean natural region contains eight departments and thirteen national parks including Bahía Portete, Corales del Rosario, and Ciénaga Grande.

It hosts the most diverse aquatic bird population in Colombia, with over 165 different species.[8]

Orinoquía region

Defined by the Orinoco River and its contiguous watershed, Orinoquía encompasses part of Colombia's easternmost borders. The region holds four departments (Arauca, Meta, Vichata, and Casanare) and four national parks, including Serranía de la Macarena and El Tuparro.

Orinoquía is mostly dry, containing tropical savannah and gallery forests as well as some wetland biomes. Its biogeographical subregions include the Meta River Plains, Arauca Marshlands and the Guaviare River Plain, the latter of which is shared with the Amazonian region.[8]

Amazonía region

The largest and southernmost of Colombia's biogeographic regions, Amazonía covers 483,000 km2 (over one-third of Colombia's territory) and shares its borders with the Andean and Orinoquían regions, Brazil, Venezuela, and Peru.

The ecoregion is subdivided into seven departments and ten national parks, including Alto Fragua Indi Wasi, Amacayacu, Churumbelos, and Chiribiquete. It is well-known for its primary biome, the Amazon rainforest, and the region is almost entirely composed of tropical rainforest and wetlands. Amazonía's biogeographic subregions include the Caquetá River Plain, Inírida River Plain (home to the Cerros de Mavecure), Putumayo River Plain, Guaviare River Plain, and Serranía de Chiribiquete.

The rainforests in Amazonía are tropical moist broadleaf forests, further subdivided into five forest ecoregions. The botanical diversity of these forests is second only to the Andean natural region with over 5300 known plant species.[5]

Insular region

The smallest of Colombia's biogeographic regions by land size, the Insular region is a collection of islands off the country's coasts in the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea. The area contains 21 islands (four pacific, seventeen Caribbean), four departments (Bolívar, Cauca, San Andrés y Providencia, and Valle del Cauca), and four national parks (Corales del Rosario, Malpelo, Old Providence, and Gorgona).[5]

In spite of its small land size, the Insular region is highly biodiverse in part due to species endemism in its island clusters. This is especially true with regards to marine invertebrate species, of which it has over 2274. Two of its most biodiverse zones are those of San Andres and Providencia in the Caribbean Sea, and those of Gorgona, Gorgonilla and Malpelo in the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific and Caribbean Insular regions have distinct climatological conditions, allowing for notably different species compositions. The former is characterized by moist rainforest with steady precipitation and high temperatures; the latter sees more seasonal variation and a drier climate.[9]

Academic contestation

The IGAC's classification, despite being the most recent official order, is arguably outdated - given that it was last updated in 1997 and based off older cartographic methods of biogeographic regionalization (as opposed to delineation on the basis of species distribution and overlap), there is some academic contestation over the regionalization and taxonomy of Colombian biomes.

A 2021 article from C.E. González-Orozoco argues that the IGAC's biome categorization stands to benefit from some revision, having been published a quarter-century ago and constructed using cartographic layering of ecosystem, watershed, vegetation, and topographical thematic maps. The cartographic method is considerably less accurate, but was more commonplace in the past due to a lack of consistent species distributional datasets. In its place, the author proposed his own biogeographical delineation based on taxic distributional overlap and species turnover of plants across Colombia, mapped using computer databases and geospatial analysis - as he described it, a "precise representation of geographic units with a unique signature of species that are similar to each other".[10]

Diversity

Colombia is among the most biodiverse countries in the world. The country's tropical environment provides optimal conditions for many species to enrich and flourish. Colombia is ranked second overall in biodiversity, falling short only to Brazil who is in first place.[3] Not only is the country highly diverse, but it also ranks third globally for species endemism.[11] Colombia fosters thousands of species that are not found anywhere else in the world.

Ecological Diversity

The Colombian landscape is an oasis for species of all characteristics. Much of the jungle has remained untouched by humans, which has allowed for speciation to occur at a very seamless rate. Because of this many plant and animal species in Colombia are native only to that region. Despite comprising only 1% of Earth's landmass, Colombia is home to nearly 10% of all species on the planet.[12] Among those species, a staggering 14% are endemic only to Colombia.[11]

Worldwide, Colombia is recognized as number one for their bird and orchid species diversity and number two for their plants, butterflies, fresh-water fish and amphibians.[13] The wildlife of Colombia inhabits a vast range of ecosystems. With nearly 314 unique terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems,[13] natural Earth systems in Colombia are complex and variable. Systems such as the hydrosphere and biosphere provide animal species with the necessary components for continual growth and reproduction

Human Population Diversity

Not only does Colombia have an abundance of species, but it also has a rather diverse population. Currently there is an estimated 51.9 million people who call Colombia their home, 86% of whom are determined to be "non-ethnic" (i.e. of mixed European ancestry) such as the Mestizo people. Much of the Colombian populace's ancestry originates in European nations like Italy, Spain, France and Germany.. As of now, Colombia is home to over 800,000 Indigenous people. The majority of these communities live on reserves, occupying roughly 27% of Colombia’s land mass.[2] Colombia's official language is Spanish, which is spoken by over 99% of the population.[14]

Plant and Animal Diversity

Much like the humans and animals, plant species in Colombia are profoundly rich and diverse. As mentioned, there are various established ecosystems within Colombia, many of which are composed of moorlands, jungles, savannah, forests, wetlands and plains[11]. The Amazonian and Andean regions are the most botanically diverse of Colombia's regions, followed by the Pacific, Caribbean and the Orinoquía region.[13] Despite this, forested regions in Colombia have seen a decrease in recent history due to human activity. Colombia’s dry forests are disproportionately affected, with only 2% of the original dry forest extension remaining today.[13]

Efforts must be taken to allow for forests to recover. All fauna populations rely heavily on plants for survival and without healthy biomass, the wildlife will begin to feel the effects. It is imperative that Colombian leaders address this issue as it is directly related to their country's future prosperity and growth.

Colombia sits at the centre of plant and animal richness. With many unique creatures that call it home, Colombia is a tropical hotspot for speciation and diversification. Not only does Colombia have a diverse range of local species, but also a diverse population as well. With a broad range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds, Colombian’s are thriving. So long is the landscapes and biogeography preserved, species will continue to flourish for years to come.

[Dillon 92978808]

Human influences

Pre-Colonial & Indigenous Modification

The extent of early human impacts on New World settings, especially Amazonia, is debatable. Certainly, whenever and wherever people were present, even in small numbers, there was some change in the terrain. People cannot live on the soil and use plants and animals for subsistence and other purposes without altering the land and the plants and animals that live there. Human-induced changes may involve equilibrium, in which the natural ecosystem heals despite changes in composition, or in which the human ecosystem is sustainable; alternatively, the changes may involve disequilibrium, in which the regenerative capacities are diminished.

Indigenous tropical vegetation management not only influenced forest and savanna structure and composition but also resulted in genetic modification as well as the formation of new species in the form of domesticated crops.[15] Manioc and sweet potato are the major food crops domesticated in Amazonia, northern Colombia and Andes, peanut (Arachis hypogaea), arrowroot, chilli (Capsicum spp.), jack bean (Canavalia spp.), cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), lerén, and yampee are among the others (Dioscorea trifida).[16]

Evidence from the neotropics indicates early human management of vegetal and, likely, animal resources by 11 000 BP, including forest clearing or utilization and maintenance of natural openings by burning, and the cultural selection of useful species through protection and planting. Where, Politis (1996, p.157) demonstrated that the high mobility of the Nukak from the Colombian Amazon is deliberately connected to the establishment of resource patches that encourage the concentration of valuable species, so ensuring long-term resource availability.[17]

Post-Colonial Industrial & Contemporary Modification

Loss of Habitat

Agriculture and extractive industries have been the primary causes of the transformation of 30% to 50% of Colombia's natural ecosystems. The majority of mining rights are in the Andes, the region with the most threatened indigenous species.

Illegal Activities

Illegal activities continue to pose a threat to biodiversity. It is believed that 40-50% of all timber obtained illegally is harvested.[18] Illegal mining, grazing, and cropping are wreaking havoc on protected regions.

Population Strain & Migration

Population pressure and migration are deforestation factors induced by an increasing need for additional and larger agricultural production areas, as well as an increased need for food, water, and energy by huge populations in distant metropolitan centres and Amazonian communities[19].

Large migrations to towns and cities are the outcome of changing economic trends—employment and education options, as well as housing and urban development—all of which lead to greater living standards. Human concentrations in metropolitan regions and related infrastructure have far broader environmental impacts than dispersed rural populations because they require growing amounts of water, energy, and natural resources from neighbouring landscapes.[20]

Hydroelectric Production & Irrigation Dams

The number of hydropower projects in the region is quickly expanding due to increased energy demands and enormous untapped potential. This is especially true in the Andean-Amazonian countries, where regional administrations prioritize the construction of new hydroelectric dams to meet energy demands. Additional hydropower plants necessitate new roadways and flooding, both of which cause deforestation.

Threats

The greatest threats to biodiversity in Columbia include global climate change, deforestation, soil erosion, and air pollution. In general, the most devastating causes of biodiversity loss in this region originate from human actions, such as commercial exploitation of resources from the logging and mining industries.

Deforestation

There is notable evidence that commercial exploitation by humans is the greatest contributor towards ecosystem devastation within the tropical regions of Columbia. Deforestation has severely impacted habitat loss for native species as forests are being consumed and fragmented by the logging industry. During the 1970's, around 908,000 hectares of natural forest in Columbia was destroyed due to farming, erosion, and the lumber industry. This figure decreased in the subsequent decade, as only around 820,000 hectares were lost annually. Between 1983 and 1993, Colombia lost 5.8% of its forests and woodlands to commercial industries.[21]

Soil Erosion & Disruption

Increased usage of pesticides overtime has contaminated previously fertile soils and led to erosion overtime in Columbia. Furthermore, the mining industry for gold and emerald in Columbia is likewise contributing towards land fragmentation, mineral disruption within the soil, and as a result water source contamination.[22]

Air Pollution

Another devastating threat to the environment caused by humanity in Columbia is the excess of vehicle emissions within more populated regions of the country (e.g. Columbia’s capital city Bogotá), contributing towards the air pollution across the region. In 1996, Columbia ranked 43rd globally for industrial carbon monoxide emissions, totalling an approximate 63.3 million metric tons[23] amassed in the atmosphere from automobile and industrial emissions. Air pollution, along with other evolving urban environmental factors, has been linked to around 7,600 premature deaths annually within Columbia.[24]

Climate Change

As climate change continues to develop globally, ecosystems within Columbian tropical regions have endured the effects of increasing temperatures and shifting environments. For instance, heavy rainfall as a result of climate change and its resulting loss of vegetation have both contributed towards soil erosion across the region. It is predicted that by 2050, the average temperatures in Columbia could increase by 3 to 4 degrees Celsius[25], which will impact agricultural productivity as well as carbon storage capacity throughout the region.

Sociopolitical Effects

Columbia has been affected by political disturbance for the last several decades due to ongoing conflict between the state and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia. This has ultimately impacted the natural environment and ecosystems within the country to a great extent as over 5.6 million residents[26] have been displaced overtime from their native rural communities into informal urban settlements, leading to land dispossession and increased vulnerability to climate-driven disasters within these newly formed, highly populated urbanized regions. Overall, the ongoing humanitarian crisis within Columbia is contributing towards climate change and biodiversity loss within the region through a multitude of complex processes.

Conservation

One of the most prominent conservation projects in this region is the BIOFIN project, which is a United Nations Development managed program that works towards demonstrating the influence of nature towards positive economies. Their initiatives within Colombia include the facilitation of biodiversity management towards the private sector in order to increase the region’s overall participation and awareness concerning biodiversity loss. Furthermore, they project to create national policies for protected areas in Colombia by 2030, as well as the formulation of restoration projects of protected areas with regional environmental importance. Overall, this project seeks to redirect government and private funding towards projects in Columbia that will contribute to decreasing the loss of biodiversity, while taking into account the impact of ongoing social movements, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the region’s distribution of public funding for environmental projects.[27]

BIOFIN’s recent coverage concerning Colombia included the participation of an event organized by the government of Colombia in September 2021, which called for an increased need to learn from Indigenous communities in order to prioritize their perspectives when formulating conservation efforts. Onno Van Den Heuvel, the Global Manager of BIOFIN, advocated for increased awareness within the global finance sector as a central focus for conservation planning within the next decade, as well as the need to create regulatory frameworks within the government in order to support local and global biodiversity goals.[28]

Another project from this region is the Biodiversity Conservation Columbia Foundation, which is a non-profit organization that focuses primarily on the protection of marine wildlife.[29] This project is entirely funded by philanthropists, conservationists, and online donations. Research about the efficiency of this project is demonstrated minimally, as it specifically targets the ocean life surrounding the Malpelo Island, west of the Colombian mainland.

References

- ↑ United States, Department of State (November 5, 2022). "A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Colombia".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "COLOMBIA POPULATION 2022". World Population Review. Retrieved October 15 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wikipedia (May 25 2022). "Biodiversity of Colombia". Wikipedia. Retrieved May 25 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Dier, Andrew. "Colombian Demographics". Hechette Book Group. Retrieved 16 Nov 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia". Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. Retrieved 16 Nov 2022.

- ↑ "Pacific/Chocó natural region". Wikiwand. November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena". Conservation International. Archived from the original on August 2011. Retrieved 16 Nov 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mendoza, Edgar (October 2011). "ESTADISTICAS BIODIVERSIDAD COLOMBIA". Estadisticas ambientales colombianas. Retrieved 18 Nov. 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Insular Region". Sula. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ GONZÁLEZ-OROZCO, Carlos E. (2021). "Biogeographical regionalisation of Colombia: a revised area taxonomy". Phytotaxa. 484: 247–260 – via biotaxa.org.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo. "Colombia Second Greatest Biodiversity in the World". This is Colombia – via Colombia Co.

- ↑ National Geographic - Kids. "Colombia". National Geographic. Retrieved October 15 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Colombia - Main Details". Convention on Biological Diversity. Retrieved October 15 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Culture, Colombian (Fall 2022). "People Of Colombia, As Diverse As Their Country". Learn More Than Spanish.

- ↑ Parker, , E.P (1992.). "Forest islands and Kayapó resource management in Amazonia: A reappraisal of the apêtê". American Anthropologist. 94: 406–428. – via JSTOR. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Denevan, W.M. (2007). [DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780195313413.001.0001 "Pre-European Human Impacts on Tropical Lowland Environment"] Check

|url=value (help). Physical Geography of South America: 265–278. - ↑ Politis, G.G. (2010). "Moving to produce: Nukak mobility and settlement patterns in Amazonia". World Archaeology. 27: 492–511.

- ↑ Street, Helena (November 5, 2018). "This is how timber trafficking operates in Colombia". OjoPublico.

- ↑ Molina; et al. (2015-10-20). "Multidecadal change in streamflow associated with anthropogenic disturbances in the tropical Andes". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 19: 4201–4213. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ Armenteras; et al. (12/2013). "National and regional determinants of tropical deforestation in Colombia". Regional Environmental Change. 13: 1181–1193 – via JSTOR. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ "Nation's Encyclopedia: Columbia - Environment".

- ↑ Fecht, Sarah (September 12, 2018). "End of Colombia Conflict May Bring New Threats to Ecosystems".

- ↑ "Nation's Encyclopedia: Columbia - Environment".

- ↑ Golub; et al. (June 2014). "Environmental Health Costs in Colombia: The Changes from 2002 to 2010" (PDF). World Bank Group. line feed character in

|title=at position 27 (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ↑ Fecht, Sarah (September 12, 2018). "End of Colombia Conflict May Bring New Threats to Ecosystems".

- ↑ "RCCC ICRC Country profiles: Colombia" (PDF).

- ↑ "BIOFIN Colombia".

- ↑ Heuval, Onno Van Den (September 2, 2021). "Placing indigenous communities and finance leaders at the heart of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework".

- ↑ "Biodiversity Conservation Colombia".

| This Tropical Ecology Resource was created by Course:GEOS303. |