Course:GEOG352/W.A.S.H. Infrastructure in Kinshasa

Introduction

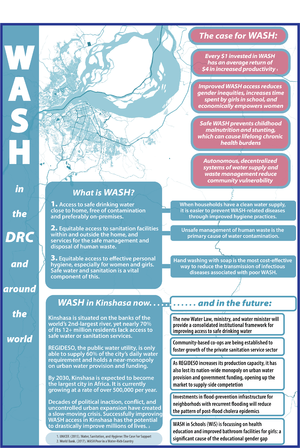

The purpose of this page is to explore the current state of WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) related infrastructure in the city of Kinshasa - the largest city and capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). WASH is used to describe access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene facilities, of which clean water, safe toilets and healthy hygiene practices form the basic areas of WASH related work. Substantially interdependent upon one another, these three elements of WASH collectively constitute a crucial component of urbanization in the global south. WASH is formalized in UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #6, which aims specifically to provide universal access to safe water, adequate sanitation, and good hygiene by 2030. While an ambitious goal, its necessity should not be understated; the state of one’s hygiene and access to safe water and adequate sanitation influences one’s entire life trajectory. The DRC is a unique region to study with respect to WASH. Paradoxically, while Kinshasa is not only situated along the banks of the world’s second-largest river but also the most water-rich country in Africa, the city’s residents have extremely poor access to safe WASH; nearly 70% of residents do not have access to safe water nor sanitation services, and furthermore an estimated one-third of the improved piped water sources within the capital of Kinshasa are contaminated with E. Coli [1]. In light of this, improving WASH within Kinshasa has the potential to dramatically improve its future socioeconomic development across a broad and interdependent swath of development indicators, including: food security, child health and nutrition, employment and productivity, education, and gender equality and empowerment.

Overview

The UN’s working definition of water security pertains to “[T]he capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of an acceptable quality water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability” [2]. Overall, WASH improvements have resounding impacts on society; UNICEF estimates that every $1 invested in WASH results in a $4 increase in a region’s productivity. Furthermore, improved hygiene is the most cost-effective form of health promotion leading to longer, happier and more productive lives. The World Health Organization estimates that poor WASH translates to a global economic loss of nearly $260 billion USD every year. These losses result from poor WASH because it is one of the major causes of preventable illness and deaths throughout the Global South. Contaminated water and poor hygiene are also leading causes of diarrheal related deaths among children. UNICEF states that “every instance of diarrhea in children contributes to malnutrition, reduced resistance to infections and when prolonged, to impaired physical and cognitive growth and development, as well as school readiness and performance" [3]. Unsafe WASH is one of the leading causes of infant mortality, childhood malnutrition, and stunting, which has “irreversible negative effects on physical and cognitive development”[4]. Improvements to WASH in Kinshasa would help to lower their youth mortality rates as well as their productivity as adults.

Unfortunately, poor hygiene and the necessity for high-risk hygiene behaviours also trap the urban poor in a vicious cycle. The promotion of good WASH is vital to individual development because a poor health environment is correlated with personal degradation and malnutrition. These result in further decreased productivity and lost income[5]. Moreover, women and girls are disproportionately affected. High-risk hygiene behaviours such as open defecation, lead to a lack of privacy and dignity which have strong negative effects on health and safety, self-esteem, education, and well-being. Also, women and girls are more likely to be responsible for their family’s supply and collection of water, where the time spent fulfilling this responsibility is known as fetch time. World Bank found that school attendance for girls increased significantly, for every hour decrease in fetch time. Therefore, access to safe water can lead to a more educated and equal society. In Kinshasa, poor quality WASH exacerbates social and economic disparities between genders, classes, and rural and urban populations[6].

Kinshasa has an especially poor WASH situation due to local socioeconomic conditions, lack of adequate sanitation, and uncontrolled landfills. In fact, many wells were contaminated with fecal matter and did not meet WHO guidelines. According to Kapembo et al. [7], contamination occurs due to “urban runoff percolation from surface water, the absence of toilet facilities septic systems’ leaky sewer lines, direct injection of wastewater effluent, and direct contamination by users.” Kinshasa lacks adequate sanitation and protection measures for wells, as exemplified by the fact that pit latrines are often located near wells. Poor WASH capacities have disproportionately influential implications on societies however within Kinshasa these are further exacerbated by a number of factors. Including, in particular, the rate of urbanization. The city's rapid urban expansion that continues to occur is outpacing the government’s capacity. The situation will only further degrade if strong measures are not taken to improve it, in light of its high population growth rate of 5.1% per year and projected population doubling from 12 million currently to 24 million by 2030 [8].

Case Study: WASH in Kinshasa, DRC

Kinshasa is situated on the Congo River. Its recent explosive population growth -a product of rural exodus and uncontrolled migration- has resulted in spatial growth and spreading southwards and eastwards from the riverbank. Furthermore, in light of Kinshasa’s already poor water quality and dire sanitation situation, the city’s anticipated high future growth is even more problematic. Though there exists sanitation infrastructure in the form of a sewer system in the central part of the city, it dates from the colonial era and has been dysfunctional for decades. Even in colonial times, a report by the colonial Belgian government cited urban hygiene and sanitation as amongst its biggest public health challenges in the colony. However, what little sewage and drainage infrastructure existed ended up falling into disrepair after the country’s independence in 1960. The effect is that while the city’s water infrastructure has essentially not improved since colonial times, the population has and continues to increase substantially, such that both water supply and quality are insufficient. Moreover, the national water utility REGIDESCO (Water Distribution Board) never took any significant role in urban sanitation due to financial constraints and the utility’s pre-occupation with water supply to the detriment of water quality considerations, which are comparatively neglected yet no less essential.

As a result of the dysfunctional sewer system, the majority of the city population (known as ‘Kinois’) rely upon shared, low-quality latrines, and only 21% of Kinois have access to unshared improved toilets. More starkly, less than 7% of these possess adequate hygiene in the form of adequate hand-washing facilities with soap. The fact that pit latrines are often located near wells is compounded by ineffective disposal of fecal matter owing to a weak sanitation service chain. With no fecal sludge treatment sites or plants in existence, there are few options other than unsafe disposal (eg. dumping), resulting in mass seepage into the ground or water bodies. Mass seepage is also a common occurrence amongst even the few improved latrines available. In a WPD survey of seven communes in Kinshasa, over 38% of households had never emptied their latrine pits, allowing it to overflow or simply move location when it was full [9], while in the Kinshasa suburb of Bumbu, Kapembo et. al. (2016) [10] found a high concentration of fecal indicator bacteria in water from shallow wells with those from human origin constituting the majority (70-95%). Moreover, the fecal contamination of the water has had tragic consequences across the country and in Kinshasa, with more than 7500 cholera cases having been identified during the 2011-2012 epidemic [11] (cholera transmission is usually through the fecal-oral route of contaminated food or water, which is compounded by poor sanitation [12]). In Kinshasa, the outbreak was traced to Camp Luka, where WASH quality is very low. 23 of the city’s 35 health zones are currently affected [13]. In conjunction with high rates of diarrhea and malnutrition amongst urban children, poor WASH access constitutes a public health crisis. Deficient clean water provision in Kinshasa also results in a number of social challenges to its populace, including affliction by diarrheal diseases and unproductive fetch time for women and girls, with households in the eastern outskirts of the city having to spend an average of 28 minutes for a round trip to their main drinking water source [14] .

Indeed, in dense urban areas of the DRC, one of the primary constraints with respect to wastewater disposal is the lack of space for consistent and universal on-site containment. Poor urban households typically construct latrines themselves or use informal masons, resulting in the construction of low-quality pits - an unfortunate reality for the 52.8% of Kinois (4.4 million people) living in poverty. While disposal options do exist in the form of private professional emptying services, they are of limited availability, being small in scale (only ~10 companies with 2-5 trucks each) and prohibitively expensive to low-income households (USD 50-100 for individual manual emptier). Moreover, even if emptying services were more ubiquitous and affordable, Kinshasa suffers from a dearth of safe disposal and treatment sites; trucks simply dump sludge at the intersection of the Yolo and Kalumu rivers or at a site near Ndola Airport in Limete commune [15]. Meanwhile, poor drainage infrastructure and drainage waterways mean that stagnant, polluted water floods the city’s streets when it rains [16].

In terms of the institutional and political situation pertaining to sanitation in Kinshasa, the city does in fact (unlike others in the DRC) possess a dedicated Sanitation and Public Works Agency. However, its near exclusive focus upon solid waste management, which is more politically noticeable, no funds have been allocated for fecal sludge management. While a decree has been signed for a sanitation fund, it is not yet operational. Furthermore, present sanitation projects in the city are of limited scale. For instance, the local NGO Congo Latrines is currently running a fecal sludge management program with up to 5000 subscribers; meanwhile, a settlement pond project financed by the World Bank’s IDA Urban Water Supply Project (PEMU) was rejected due to local resistance and a lack of clarity regarding institutional ownership [17].

Recommended solutions to the sanitation crisis in Kinshasa include: the revival of earlier plans for a safe fecal sludge treatment site under the institutional responsibility of the proposed sanitation fund FONAK (Alain KALUYITUKADIOKO Foundation), the improvement of existing waterways in the city to drain rain and wastewater more effectively, and the implementation of a study on the private market for high-quality, low-cost latrine construction [18].

Another solution, particularly applicable to peri-urban areas of Kinshasa, could be the piloting of decentralized wastewater treatment plants, in collaboration with water user network associations (ASUREP’s). Indeed, Bedecarrats et. al. (2016) [19] analyzed the role of a local NGO supported by different donours in the promotion of decentralized water system (DWS) that have spread to the city’s outskirts. The strength of such decentralized water systems lies in their social capital: their capacity to manage a close and relatively transparent relationship with users in a predominantly informal context, not requiring any land registry or postal service, nor encountering the difficulties of access during the rainy season. The small size of DWS’s also fosters close ties between the user and network management, allowing for the user to know who to contact in case of a system breakdown.

Lessons Learned

To date, the most successful WASH projects in the DRC have been in the eastern border provinces, especially in the Rwanda-Burundi and Kivu-Maniema areas.[20] A combination of factors have led to this success. Proximity to neighboring countries brings improved access to material goods, while a sustained UN presence in the region over the course of two decades (a legacy of the Rwandan Civil War) has provided community infrastructure development projects with the time and support to mature into self-sufficient systems.

While the smaller interior communities do not face the same pressing population challenges as Kinshasa, a significant urban-rural water access disparity persists. Over the years, distribution of limited funding has been pragmatically focussed in the most densely populated areas of the country, which in turn forces more families out of their rural homes and into the already-overburdened cities.

Lessons learned in the eastern DRC (and elsewhere) are now being applied to Kinshasa’s municipal strategy, as well as to rural communities: decentralization, autonomy, and long-term commitment in conjunction with both local and international NGO’s. The newly passed Water Law and the creation of a dedicated water ministry will facilitate the establishment a more robust institutional framework for the provision of WASH services, and the demonopolization of REGIDESO has created new competitive markets for private-public partnerships. At the same time, a focus on autonomous infrastructure systems will reduce community vulnerability to political, social, and economic turmoil. Ultimately, in alignment with the SDG’s, a practical, pro-poor, comprehensive approach aiming for a safe sanitation service chain must be considered. Most importantly, components of a comprehensive strategy applied not just to Kinshasa but to other under-resourced urban contexts in the Global South must include the construction of safe disposal sites - latrine emptying in isolation does not solve, but rather merely displaces the systematic public health problem of a lack of formal sites for the safe disposal of fecal sludge. Nonetheless, other essential components include the development of affordable latrines and decentralized condominium sewer systems, end-use portable water treatment systems, and concerted planning and improvement of existing waterways to improve the drainage of rain and wastewater.

References

- ↑ World Bank. (2017). WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: World Bank.[pdf] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/651601498206668610/pdf/116679-22-6-2017-12-42-8.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018]

- ↑ UN Water. (2013). Water Security & The Global Water Agenda. www.unwater.org/app/uploads/2017/05/water_security_summary_Oct2013.pdf [Accessed Apr. 2018]

- ↑ UNICEF. (2015). Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: The Case For Support. [pdf] Available at: https://www.unicef.org/publicpartnerships/files/WASHTheCaseForSupport.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ World Bank. (2017). WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: World Bank.[pdf] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/651601498206668610/pdf/116679-22-6-2017-12-42-8.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ UNICEF. (2015). Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: The Case For Support. [pdf] Available at: https://www.unicef.org/publicpartnerships/files/WASHTheCaseForSupport.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Kapembo, M et. al. (2016). ‘Evaluation of Water Quality from Suburban Shallow Wells Under Tropical Conditions According to the Seasonal Variation, Bumbu, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo'. Expo Health 8 [online] (June), pp 487-296. [pdf] Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12403-016-0213-y [Accessed Mar. 2018].

- ↑ World Bank. (2017). WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: World Bank.[pdf] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/651601498206668610/pdf/116679-22-6-2017-12-42-8.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Kapembo, M et. al. (2016). ‘Evaluation of Water Quality from Suburban Shallow Wells Under Tropical Conditions According to the Seasonal Variation, Bumbu, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo'. Expo Health 8 [online] (June), pp 487-296. [pdf] Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12403-016-0213-y [Accessed Mar. 2018].

- ↑ IRIN. (2012). ‘Poor sanitation systems hinder fight against cholera’, Reliefweb,f 30 April.[online] Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/poor-sanitation-systems-hinder-fight-against-cholera [Accessed Feb. 2018]

- ↑ World Health Organization (2010). "Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper" (PDF). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 85 (13): 117–128.http://www.who.int/wer/2010/wer8513.pdf Accessed Apr. 2018.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2018). Humanitarian Health Action: Democratic Republic of the Congo news releases and feature stories. [pdf]] Available at: http://www.who.int/hac/crises/cod/releases/en/ [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Bedecarrats, F. et. al (2016). “Building commons to cope with chaotic urbanization? Performance and sustainability of decentralized water services in the outskirts of Kinshasa.” Journal of Hydrology. Accessed Apr. 2018. ttps://ac.els-cdn.com/S002216941630453X/1-s2.0-S002216941630453X-main.pdf?_tid=b574ae56-53cb-49c7-9eb8-fa0760588f54&acdnat=1523049536_93ceb8bf739cdb9ff8c07166fef95e06.

- ↑ World Bank. (2017). WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: World Bank.[pdf] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/651601498206668610/pdf/116679-22-6-2017-12-42-8.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ IRIN. (2012). ‘Poor sanitation systems hinder fight against cholera’, Reliefweb, 30 April.[online] Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/poor-sanitation-systems-hinder-fight-against-cholera [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ World Bank. (2017). WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: World Bank.[pdf] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/651601498206668610/pdf/116679-22-6-2017-12-42-8.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Bedecarrats, F. et. al (2016). “Building commons to cope with chaotic urbanization? Performance and sustainability of decentralized water services in the outskirts of Kinshasa.” Journal of Hydrology. Accessed Apr. 2018. ttps://ac.els-cdn.com/S002216941630453X/1-s2.0-S002216941630453X-main.pdf?_tid=b574ae56-53cb-49c7-9eb8-fa0760588f54&acdnat=1523049536_93ceb8bf739cdb9ff8c07166fef95e06.

- ↑ World Bank. (2017). WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country: A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Washington, DC: World Bank.[pdf] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/651601498206668610/pdf/116679-22-6-2017-12-42-8.pdf [Accessed Feb. 2018].