Course:GEOG352/Public Spaces: Race, Class and Access to Education in Cape Town, South Africa

By: Claire Anderson, Jemma Denton, Elsabe Fourie and Kirsty Summers.

We are going to be looking at public spaces in South Africa and how differences in ethnicity and class lead to inequality regarding the access to education, access to future opportunities and access to a better quality of life.

Public space and its relation to political participation broadly relates to the ways in which individuals maneuver through a city based on socially constructed norms. These may include notions such as class, language, gender, age, ethnicity and sexuality. Within these public spaces, some individuals may feel excluded from participating, either partially or entirely, whilst others may feel more included. This level of inclusion in regards to class and social status can then affect access to basic services such as education, and in countries like South Africa, where racial divides are highly prevalent, these problems of division within public spaces are persistent and problematic.

South Africa gained its independence from Great Britain in 1961 (Davenport and Saunders, 2000), [1] but its history of racial division extends for many years prior. Cape Town, located in the Western part of South Africa, is one of the country’s three capital cities. In terms of its population it ranks as the second most populous behind Johannesburg (World Population Review, 2018).[2] South Africa as a whole is often nicknamed the ‘Rainbow Nation’ due to its wide cultural diversity, and Cape Town is no exception to this. Within this multicultural city, however, are deeply rooted notions of the relationship between race and class. As we will uncover, this ultimately shapes the societal norms and determines how people then access the city’s public spaces, including the quality of education that they feel as though they are able to obtain.

Overview

Public Spaces & Education

Spatial exclusion in public spaces is magnified in the Global South. Largely, this is due to colonial constraints and ideals that remain embedded in much of the city’s structure. Whilst we defined public space within the introduction it is a tricky notion to then apply in the real world, as different disciplines give the term different and partially overlapping meanings. Politically, public space can be seen as a metaphorical space of debate. Within the context of Cape Town, this manifests through the debate of apartheid, whereby White hegemony aims to exclude Africans from this political space by denying them franchise and other basic rights of citizenship. Judicially, public space can be seen as the public land owned by public authorities. Again, within the context of Cape Town, the White-dominated state owned a considerable amount of land in the urban areas. This allowed for the shape of the city to be controlled, facilitating racial control. Socially, public space should be welcoming to a plurality of uses and perspectives; in social spaces, people are simultaneously on show and in the public eye. As a result of this, public space can have a mixed variety of these components, ultimately shaping how citizens view the city.

The Importance of Public Spaces & Education in Cape Town

Charlotte Lemanski [4] has defined Cape Town as a ‘City of Exclusions’, with systematic racism and historical social constructions limiting the opportunities for those living in impoverished conditions. If a public space is perceived as being only accessible to a certain race or class grouping, then those who do not meet this 'criteria' are excluded. Of particular importance is the access to education. Obtaining access to education is often viewed as an important step towards a better quality of life as it can lead to further opportunities such as career prospects (Ross, 2010).[5] In the context of Cape Town, this can determine aspects such as whether a low income family have the opportunity to escape extreme poverty conditions. Within Cape Town the most stark visible inequalities can be seen when comparing communities such as Freedom Park, which is populated with dense slums, to highly affluent neighbourhoods like Rondebosch. The role that race and class structure plays therefore not only influences which neighbourhoods and parts of the city people move to, but also the quality of their education and access to further opportunities.

Scale & Scope

Furthermore, Cape Town’s continued problems surrounding race and class segregation in the post-Apartheid era has left the region in a grey area of development. Citizens are legally now free to move and live without constraint but the social constructs of the past still continue to define the status and opportunity of Cape Town’s residents. Settlements throughout Cape Town are identified as being similar to many places within the Global North, developed and prosperous. Yet, on the periphery a large part of the population in these areas have similar problems more identified with developing countries, such as lack a infrastructure and access to basic necessities. The housing distribution of the past was intended to keep black residents on the urban periphery in informal settlements (Levenson, 2017).[7] The mass amounts of citizens that were pushed to these informal settlements continue to be marginalized to an extent due to their race and class identity. These Individuals are still limited to the confines of their immediate community. With education being a key factor in the role of development, but also in determining a citizen's future opportunities, geographical proximity to schools plays a role in who may access them. A major quantity of secondary schools in Cape Town lie in and around Rondebosch and northern suburbs. In contrast, formal secondary schools exist sparsely in areas of the Cape Town flats which is the location of many informal settlements (See Figure 1). The vivid contrast of the location of secondary schools reinforces the grey area of development that Cape Town is in. Regarding policy, the South African Constitution states that all individuals have the right to basic education in their own language, and that there are “enough school places” in order to correct and offer a solution for the past discriminatory laws (Goitom, 2016).[8] As the majority of the schools are located at a far distance from the Cape Flats and Slum areas such as Mitchell's Plain, this indicates that there has been limited effort regarding the provision of adequate access to schools for peripheral residents since Apartheid. Therefore, by allowing the affluent areas to continue to develop whilst the surrounding areas are neglected, the surrounding areas are left lacking in the institutions that are needed to help further devlop the areas. The extent of inadequate access to education is an ongoing problem as even with positive policy alterations there has been limited action to result in impactful change. With race and class hierarchies continuing to determine the geographical location of settlements, the availability of access to public space and opportunities to those who are located in the urban periphery remains limited.

Global Phenomenon? Local Problem?

Access to urban public spaces is a global phenomenon that affects countries in both the Global North and Global South. Socio-spatial dialects drive not only the norms that dictate who has access to space in terms of race, religion, class and gender, but also the policies that produce and reproduce these spaces. Although affecting each country on different scales, the occurrence of discrimination influencing access and opportunity is an overarching global problem. In regard to access to education, inequalities are visible on both the local and global scale, but also within countries between different spaces. Globally, limited education access is often a characteristic of developing countries due to lack of infrastructure or funds. Locally, in South Africa the side effects of a separatist regime have created a system that continues to limit educational opportunity to citizens based upon race and class hierarchies. This highlights different access in regards to more affluent spaces and less affluent spaces, within the country of South Africa, but also within the city of Cape Town. South Africa gives responsibility to each of its nine provinces to control their own education departments to implement the policies of the national department. Allowing each province to maintain control of their education systems separately allows for further potential barriers due to the different race and class groups within each province.

In order to link our project to central themes of the course, it is vital to emphasise global urban theories. Traditional western theories of the Global North cannot simply be transposed onto the developing urban spaces in the South due to differing local processes. There is no 'norm' of urban development around the world, as cities take various forms and allow for the conceptualisation of spaces to begin from anywhere (Watson, 2009).[9] In recent times moving beyond the binaries of formal verses informal is vital to the changing perspective of the growing global focal points as cities in the Global South.

Case Study: Education in Cape Town

In Cape Town there is a dualistic divide within the city: a division of physical spaces and a societal division of the affluent white and the black underclasses (Hill and Bekker, 2014).[10] These views on identity are still ingrained within many societal norms today. The historic embedded legacies of colonialism and the ongoing repercussions of the Apartheid have resulted in Cape Town becoming a city of 3.7 million residents. However, one third of the total population now inhabit Shanty Towns and informal settlements on the periphery of the urban core (Milne, 2017).[11] These legacies of colonialism impact the present day. This is evident through the work of Patrick Wolfe (2006)[12] who argued colonialism is a structure and not an event. This explains that the processes of colonialism are not isolated in space and time, but are continually implicating contemporary society.

This is evident through the systematic structure of education as shown by Villette (2016),[14] who argues to this day disparities in primary school funding still exist between the institutions that have a predominantly black population. In the 1970s the state spent an annual amount of R644 on each individual white pupil, in comparison to each individual African pupil who received R139 (Villette, 2016).[14] This is evidence that the ethnicity you identity with still impacts your access regarding the quality of your education, and public space. Furthermore, this historic process has shaped the physical space of the city resulting in clear divides between wealthier gated neighbourhoods and the informal settlements (See Figure 2). This occurred through the historic practices of spatial engineering, which describes how the wealthier white middle classes were clustered in the heart of the urban area, where infrastructure such as railways were used to reinforce spatial divisions (Wainwright, 2014).[15] This shows how space is used to exclude certain members of the population from so called ‘public spaces’, therefore public spaces are targeted to only be used by a certain demographic of the public. This calls into question who as has the right to the city, as argued by Lefebvre (1968).[16] Individuals excluded to the periphery do not receive the same benefits regarding public space and therefore educational access.

An example of this is Freedom Park, an informal settlement in Cape Town located on Mitchell’s Plain (See Figure 3), which has an unemployment rate of 39% making it one the poorest districts in Cape Town (Brown-Luthango et al., 2017).[17] Generally within these areas there is a lack of access regarding public space and basic infrastructure such as clean water, garbage collection and public transport. The poor quality and infrequent maintenance of these amenities can impact how people use the space and move between the urban centre and the peripheral slums. Additionally, Chant (2013)[18] highlights how children lack the capacity for an essential studying space in slum housing due to the fact they do not have access to basic infrastructure, peaceful surroundings or electricity. Therefore, this limits their progress and ability within education impacting how well individuals can integrate within society and utilise public space. Moreover, Tsujita (2013)[19] argues that the main reason children between the ages of 5-14 residing in informal settlements lack access to education is due to parents carrying unfavourable views surrounding the idea of education. Therefore, they choose against the idea of giving their children the opportunity to an education.

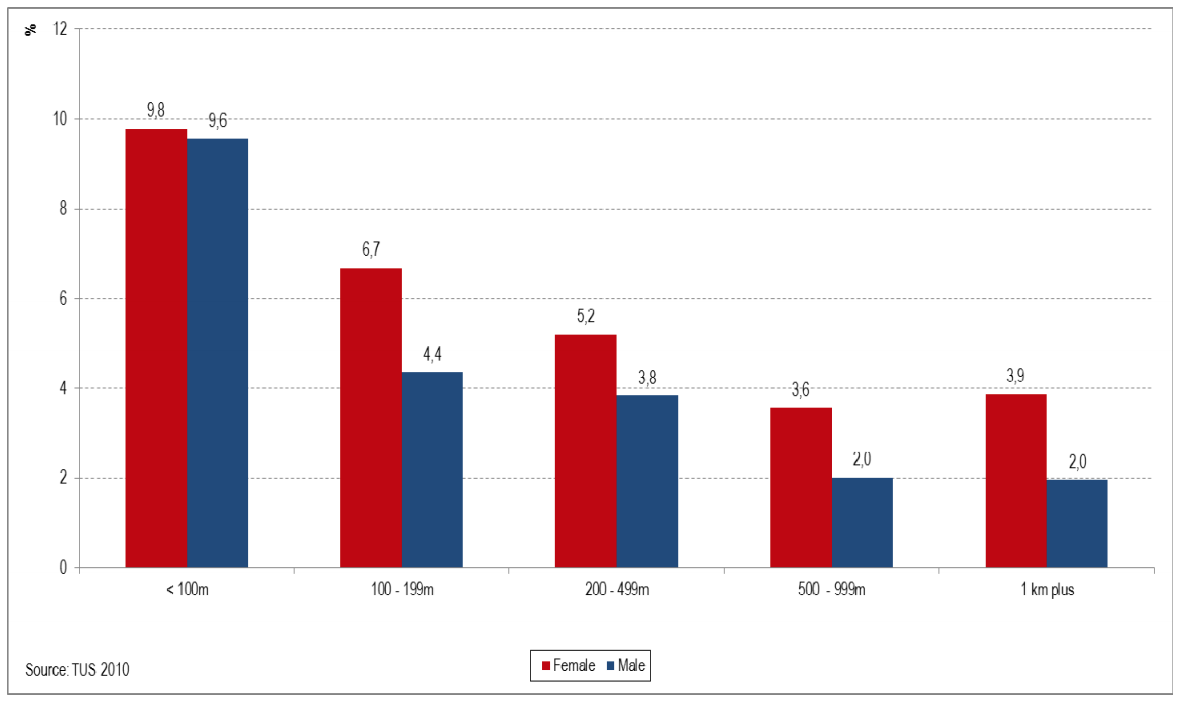

Educational access has not only been racialised, but also gendered, creating an expectation on women to prioritise domestic roles over their education (Ross, 2010).[5] Arguably this will affect women’s educational attainment and attendance regarding important aspects such as contraception and health. Furthermore, females also suffer from ‘time-poverty’, which is where females are compelled by societal expectations to use their time to collect water for their families, which impacts the time and energy that they have left to direct towards education (Chant, 2013).[18] In Cape Town when the water source is 1km or more away from their settlement females are twice as likely to collect this water compared to their male counterparts (Statistics South Africa, 2013)[21] (See Figure 4). Using the ideas of Wright (2011)[22], this is an example of how in the Global South ideas around women being responsible for household duties are naturalised.

A potential solution regarding these issues is presented in the 2017 UN report.[24] This reports argues that public space is a catalyst for providing access to education, income generating activities, and political engagement; with a youth group in the Mathare Slum creating their own public spaces in the form of a youth centre and football fields. This could be applied within the context of Cape Town, where the re-claiming or creating of public spaces could help societal integration between the two racialised sectors. The project undertaken in the Mathare Slum involved creating a football field and a training centre specialising in youth technology that has ultimately become an enabler of education by increasing the chances for individuals to gain access to educational programmes. Similarly, d’Allant (2013)[25] describes how in the informal settlements, thirty two basketball courts were opened in partnership with NBA stars, which has resulted in young individuals partaking less in criminal activities and increasing their engagements in team work and discipline. This enhancement of opportunities through forms of informal education has allowed the reclaiming and development of spaces that link into the growing informal economies of the Global South. Arguably, this goes against dominant views regarding education in the Global North where informal economies are deemed an unsuitable form of education. By generating new educational pathways into informal economies it betters the opportunities for the racialised population. This echoes the improvements required to create a more inclusive economic and educational structure in places such as Cape Town. Backed by Chant (2013),[18] there is evidence of educated young women, even through informal sectors, having increased accessibility to public spaces and have been proven to be happier individuals. Therefore, it can be concluded that by taking into account access to public space, education is a key method for reshaping and redefining spaces throughout the Global South (Ross, 2010).[5]

Lessons Learned

Access to education is a complex problem that is occurring in many developing countries around the world. In light of today’s economy, a basic education is essential for obtaining most entry to professional level jobs. When there are race, gender, culture, class or any discriminatory restraints put on people that are trying to access education, it continues to limit the potential progress for that region. As it has been reiterated the continued segregation based on class, gender, and race is what is limiting access to public space for people of colour within South Africa. South Africa, amongst other similar regions with historical racial segregation such as countries within Latin America, should take into account that a main aspect denying them of further devllopment is a lack of eagerness for equality. These regions need to actively focus on integrating the marginalized citizens into their societies. One way to push this integration is through the positive reclaimation of public space, for example successfuly beggining to be carried out within the Methare Slum. Furthermore, Open Streets Cape Town is a non-profit organisation that is striving to connect the people of Cape Town through redefining the use of public space. Essentially, they open up a street on a particular day to anyone and everyone in the hopes of creating a positive community atmosphere through activites such as games, music, and vendors. This concept had extremely positive outcomes and proved to create a positive mixed race and class communal public space for that day (Open Streets, 2017).[26] The assistance of non-profit organisations and community and youth groups is essential in breaking down boundaries of inequalities in ways that the government, although now democratic, may not seek to the same extent. Urban centres facing similar issues around the access to public space and education to Cape Town have the potential to recreate public space by defying the racialized norms of the past, thus creating a new unified future for their region.

Infographic

Cape Town Public Spaces: Race, Class & Access to Education

References

- ↑ Davenport and Saunders (2000) South Africa: A modern history. Springer.

- ↑ World Population Review (2018) Cape Town Population. Retrieved from: http://worldpopulationreview.com//

- ↑ AndBeyond (2018) Cape Town. Google Images.

- ↑ Lemanski, C. (2006) Spaces of exclusivity or connection? Linkages between a gated community and its poorer neighbour in a Cape Town master plan development. Urban Studies, 43(2), 397-420. 1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Ross, F (2010) Raw Life, New Hope : Decency, Housing and Everyday Life in a Post-apartheid Community. University of Cape Town Press, Claremont

- ↑ Western Cape Education Department (2018) Find-A-School Map. Google Maps. Available:http://wcedemis.pgwc.gov.za/wced/findaschool.html

- ↑ Levenson, Z. (2017). Living on the Fringe in Post-Apartheid Cape Town. Contexts, 16(1), pp. 24-29.

- ↑ Goitom, H. (2016) Constitutional Right to an Education: South Africa. Accessed: 14/02/2018. <https://www.loc.gov/law/help/constitutional-right-to-an-education/southafrica.php>

- ↑ Watson, V. (2009) Seeing from the South: Refocusing urban planning on the globe’s central urban issues. Urban Studies, 46(11), pp.2259-2275.

- ↑ Hill, L., and Bekker, S. (2014) Language, residential space and inequality in cape town: Broad-brush profiles and trends. Etude De La Population Africaine, 28(1), 661-680.

- ↑ Milne, N. (2017) The Tale of Two Slums in South Africa, As Residents Seek to Upgrade Their Lives. Huffpost. Accessed: 11/02/2018. <http://www.huffingtonpost.co.za/2016/12/14/the-tale-of-two-slums-in-south-africa-as-residents-seek-to-upgr_a_21627869/>

- ↑ Wolfe, P. (2006) Settler Colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), ppg. 387-409.

- ↑ Miller (2005) Divide between rich and poor in Cape Town. The Advertiser. DOI:http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/travel/divide-between-rich-and-poor-in-cape-town/image-gallery/d71a7af0956ad6281b440ec243551256.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Villette, F. (2016) The Effects of Apartheid’s Unequal Education System Can Still Be Felt Today. Cape Times. Accessed: 10/02/2018. <https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/the-effects-of-apartheids-unequal-education-system-can-still-be-felt-today-2035295> Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Villette2016" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Wainwright, O. (2014) Apartheid ended 20 years ago, so why is Cape Town still ‘a paradise for the few’? The Guardian. Accessed: 13/03/2018.

- ↑ Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la ville [The right to the city] (2nd ed.). Paris, France: Anthropos.

- ↑ Brown-Luthango, M., Reyes, E. & Gubevu, M. (2017;2016). Informal settlement upgrading and safety: experiences from Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 471-493.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Chant, S. (2013) Cities through a “gender lens”: a golden “urban age” for women in the global South? Environment & Urbanization, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 9-29 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Chant2013" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Chant2013" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Tsujita, Y. (2013) Factors that prevent children from gaining access to schooling: A study of Delhi slum households. International Journal of Educational Development, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 348-357.

- ↑ Design Indaba (2009) The History of Freedom Park before 10x10. Design Indaba Blog. DOI: http://designindaba10x10.blogspot.ca/2009/02/history-of-freedom-park-before-10x10.html

- ↑ Statistics South Africa, (2013). Gender Statistics in South Africa, 2011. Private Bag, Pretoria. Pg. 15

- ↑ Wright, M. (2006) Disposable women and other myths of global capitalism. New York: Oakland: AK Press. Chapter 3: Manufacturing bodies.

- ↑ Statistics South Africa (2011) 2011 Statistic Report. South African Government.

- ↑ United Nations (2017) Youth, Informality And Public Space: A Qualitative Case Study on the Significance of Public Space for Youth in Mlango Kubwa, Nairobi report. Tone Standal Vesterhus, University of Oslo.

- ↑ D’Allant, J. (2013) How the Urban Poor Are Reclaiming Public Space. Huffpost. Accessed: 13/03/2018.

- ↑ Open Streets (2017) MEDIA RELEASE: Open Streets Main Road - the sequel. Open Streets. Accessed: 20/03/2018. <https://openstreets.org.za/news/media-release-open-streets-main-road-sequel>

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |