Course:GEOG352/Public Space in Nairobi

| Republic of Kenya Jamhuri ya Kenya | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Information | |

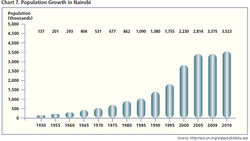

| • Capital: Nairobi (14th largest city in Africa)

• Population:

• Area: 582,646 sq km (224,96 sq miles)[2] • Major Languages: English • Kiswahili[2] • Currency: Kenya shilling[2] • Principal Religions: Christianity (83%) • Protestant (47.7%)[3] • Important Cities: Mombasa (465.000 people) • Kisumu (185.000 people) • Nakuru (163.000 people)[4] • Urban Population: 39%[4] • Population Growth: 2%[4] | |

| Government | |

| • President: Uhuru Kenyatta

• Deputy President: William Ruto | |

| Public Spaces in Nairobi | |

| • Public Open Spaces: 8.2%[5]

• Six Major Open Public Spaces

| |

| Infographic | |

|

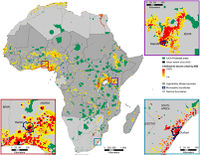

Introduction

Africa is one of the fastest urbanizing regions of the world and this process is mainly informal as “‘auto constructed’, makeshift shelter responses house 62% of African urbanites…. [which] implies that the bulk of city building can be attributed to actors outside of the state and formal business sector” [6]. On the African continent, and most of the Global South, urban and economic informality are the norm. The spatial dimensions of such informality translate into the majority of the urban populations living in informal settlements, in areas lacking essential civic services and amenities and articulated public spaces [7]. As noted by Roy (2009), informality is a mode of production of space that extends beyond the economic sector, which renders the character of public spaces in informal urban areas unique to their contexts[8]. Public space is defined as “all spaces publicly owned or of public use, accessible and enjoyable by all for free and without a profit motive” [5]. Public space is a necessity which can create "prosperous, livable, and equitable cities in developing countries" [9]. Overall, public spaces have become a basic need of the urban context of cities around the world. Public spaces foster economic development and environmental sustainability, and also serve as cultural spaces to promote sense of community and healthy societies. Not only they are important in cities of the global south, but are deemed relevant spaces around the globe inspiring unity and identity. This study investigates the state of public spaces in Nairobi and issues of accessibility of these spaces based on class.

Overview

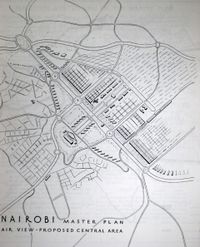

Nairobi is a cosmopolitan, multicultural city in Kenya, originated in the late 1890s as a colonial railway settlement and later on developed as the principal industrial center of the country. Nairobi is the largest city in Kenya and the 14th largest city in Africa with 6.54 million people[10]. The city plays an important role in the community of Eastern African states and is the headquarters of important regional railways, harbors and airway corporations. Nairobi is currently undergoing a construction boom influenced by the post-independence period which has accelerated the migration process of people from the rural areas to the city leading to a rapid population growth. A Master Plan was created in 1948 which allocated money specifically towards public space, however, the city had experienced a surge in population growth, and doubled the amount by 1975, which exceeded the number of individuals that the 1948 Master Plan of Nairobi was meant to accommodate for. Existing public spaces are thus inadequate to meet the needs of the current large population. As public spaces are instrumental in building social cohesion, this shortage of public spaces in Nairobi is an important concern to be addressed in order to ensure the resiliency of the community.

Case Study

The Past, Present, and Future of Historical and Municipal Planning Documents for Public Space

The Past

The original 1948 Master Plan included approximately 30% of land area for public space, and took into account “slum clearance, adequate open spaces, public authorities had sufficient access to land, and the beauty spots of the city were well conserved” [11]. A 1972 revised Master Plan did not get approved because of competing political interests, also, this revision did not prioritize public space.

The Present/Future

The future of Nairobi’s public space lies in the hand of the 2030 City Masterplan. The 2030 Masterplan is the first revision of the 1970 plan in about 40 years. This revised plan proposes increased involvement of the private sector.

This plan addresses six specific areas: transportation; governance and institutions; environment; land use and human settlements; population, social systems and urban economy; and infrastructure[12]. It includes the establishment of more public parks and green spaces, and to ensure that these public spaces are in harmony with the natural surroundings. The plan to create a “new town” has been established in the 2030 vision. The 2030 Master Plan includes the creation of more than a "...dozen commercial centres to create multiple economic arteries in the city..." [13]

The Government of Nairobi has been looking into increasing the privatization of public spaces. The privatization of public space may take away sources of leisure and recreation from low-income citizens, to provide increased safety and security to higher-income citizens. Privatization of gated neighbourhoods has both its positive impacts and negative. Some neighbourhoods require payment for a once or yearly membership along with fees for security and other services. Those who can afford to pay can benefit from increased security and access to certain public spaces.

Privatization of Public Spaces

Public spaces are important for building community and a sense of social unity. They are places where people can socialize and spend time in an atmosphere of freedom and security. However, as Nairobi is becoming increasingly urbanized, the city has seen several public spaces come under attack due to illegal alienation of public land specially in low-income areas.

The 1948 Master Plan for Nairobi City had allocated 24.96 km2 of land for public open spaces, which represented 27.5% of the total land area of the city (90.64 km2)[11]. The African city has six major public open spaces: Uhuru/Central Park, Jamhuri Park, City Park, Arboretum, Kamkunji, Jevanjee Gardens and two forests areas (Karura and Ngong Road Gardens)[5]. Serious threats to public open spaces have become more evident since the 1970s with increased expansion of formal and informal settlements in total disregard of the zoning specifications provided in the Master Plan.

- The national land policy identifies the problem of illegal alienation of public land for private use. The policy addresses the prevalence of public land in contrast to privatization through the illegal allocation of such land to private corporations with total disregard to the public interest during the post-independence period, popularly known as land-grabbing[11].

- The illegal alienation of public open spaces is blamed on poor governance and the total disregard of the existing by-laws drafted in the national land policy.

- For example, the alienation of parts of City Park for private use was in contravention of City Council by-laws[11]. The by-laws established for City Park are aimed at preventing damage, ensuring security and conservation of biodiversity. However, the park has suffered neglect, overcrowding and alienation for private use losing 50 acresof its land to private developers through illegal alienation by state officials[11].

- The rising urban population and loss of these spaces to private developers has heightened the demand for public open spaces. The establishment of private businesses in land originally intended for public use has created land use conflicts because of noise, solid and liquid waste, and overcrowding [5].

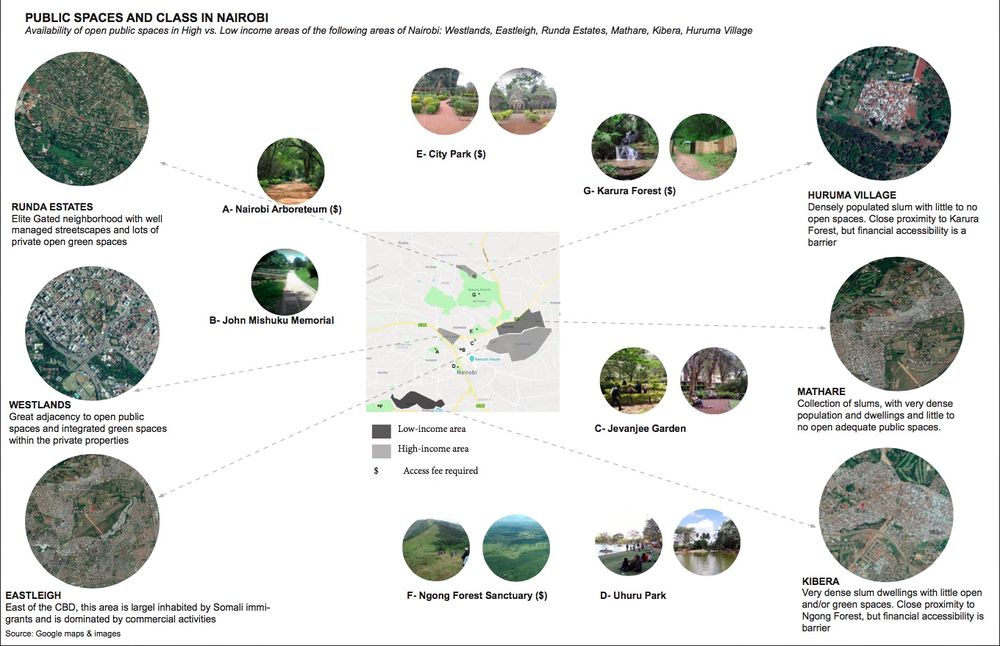

Comparision: Low Income Area vs High Income Area

Types

Parks, Community centers, Informal settlements (such as Kibera) are usually considered as public open space in low income areas. Examples of public open space in high income areas are the City Park (which was planned for the Parklands neighbourhood) and Nairobi C.B.D. (Central Business District).

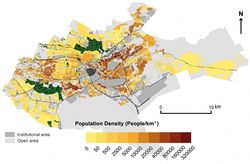

Area

Public spaces are distributed unequally between high-income areas and low-income areas. The public space per capita area is higher in high-income areas. For example, public space in Mathare is less than 2 m2 per capita and of lower quality, whereas public space in Westlands is over 50 m2 per capita and of higher quality [14].

Quality

Low-income area

Kibera is the biggest informal settlement in Nairobi. It is heavily polluted with garbage and dust. The river runs through the informal settlements are used to dispose of waste and are flooded during the rainy season, preventing the access of more residents to their hillside homes.

High-income area

Although the City Park mentioned above was planned in the middle-and-high income area, the major part of visitors are low-income people. This is because low-income informal activities would be attracted by the alienation of parts of the park for private use [11]. The influx of a large number of low-income users increases security risks such as gender violence, and also lead to decrease in quality of the park. Park congestion, noise, and broken facilities are also problems in City Park. The lack of facilities is also a problem in C.B.D. The current recreational infrastructure is insufficient to support social life [15].

Therefore, one common feature of the quality of low-income and high-income public space is the lack of facilities. In addition, the lack of sanitation facilities and security risks are considered as problems in Nairobi informal settlements.

Lessons Learned

- Nairobi has become “increasingly stratified, with people sticking to their class,” [14] by investing in public spaces, citizens have more opportunity to interact with those around their community which can be transferred to many other cities in the global south.

- While both low-income and high-income areas within the CBD areas of Nairobi are all within close proximity of public spaces (parks, gardens, forests), cost is still a barrier for low-income users.

- The investigated low-income areas (Kibera, Mathare and Huruma) are all located by an urban forest, which require access fees. Within these neighborhoods, classified as slums, there is inadequate infrastructure (streetscapes, waste management,…). High-income areas, on the other hand have adequate and clean streetscapes and abundant private green spaces within individual properties, in addition to the proximity to existing city parks and gardens. Nonetheless as the population size of Nairobi has grown, the availability of the present public spaces is inadequate to meet the needs of the people.

- The Nairobi 2030 Metropolitan "...growth strategy aims to transform the Nairobi metropolitan region into a world class African region that offers sustainable wealth creation and a high quality of life for its residents, by the year 2030." [17]

- Privatization is one of the reasons for the reduction of public space in Nairobi. Private ownership transforms the original public space into public markets or restaurants, which not only deprives the park of its original recreational function, but also leads to an increase in the discharge of sewage and waste [11]. In order to solve this problem, the government may need to re-plan public lands, strengthen management, or cooperate with social organizations [11].

References

Reference List

- ↑ Countrymeters. (2017). Kenya Population. Current Population of Kenya. Available at: http://countrymeters.info/en/Kenya

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 BBC News. (2018). Kenya Country Profile. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13681341

- ↑ Casa Africa. (2017). Países de Africa: Kenia. Available at: http://www.casafrica.es/fich_pais.jsp?DS52.DATAID=13263

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kenya Information Guide. (2015). Facts About Kenya. Kenya facts: Information at a Glance. Available at: http://www.kenya-information-guide.com/about-kenya.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 UN-HABITAT. (2016). Nairobi Community-Led, City-Wide Open Public Space Inventory and Assessment. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "UN" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Pieterse, E. 2011, "Grasping the unknowable: coming to grips with African urbanisms", Social Dynamics, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 5-23. DOI: 10.1080/02533952.2011.569994

- ↑ Gouverneur, D. (2014). Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements. Routledge, London.

- ↑ Roy, Ananya. (2009). The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory. Regional Studies. 43. 819-830. 10.1080/00343400701809665.

- ↑ Kim, S. (2015). Public spaces - not a “nice to have” but a basic need for cities [online] Available at: http://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/public-spaces-not-nice-have-basic-need-cities [Accessed April 4, 2018]

- ↑ World Population Review. (2018). Kenya Population. Available at http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/kenya-population/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Makworo, M. & Mireri, C. 2011, "Public open spaces in Nairobi City, Kenya, under threat", Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, vol. 54, no. 8, pp. 1107-1123 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "makworo" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Post navigation. Future Cape Town, September (2011) from http://futurecapetown.com/2011/09/future-nairobi-a-2030-city-masterplan-6-new-towns/#.WsFt2JM-dE4

- ↑ Makena, Joy. (2014). Nairobi maps its future with new city master plan. Available at: http://www.constructionkenya.com/2212/nairobi-city-masterplan/

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Allibhai, Narissa. (2017). Our Land - Open Space in Nairobi. Available at http://www.peopleinthemargins.com/public-space-in-nairobi/ [Accessed on April 3rd, 2018] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "AN" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ University of Nairobi, (n.a), The Quality of Open Spaces in the C.B.D. in Nairobi, Available at http://architecture.uonbi.ac.ke/node/1294 [Accessed at April 3rd, 2018]

- ↑ Google Maps & Images (2018) Available at: https://www.google.ca/maps?q=nairobi+google+maps&um=1&ie=UTF-8&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjSgqKZ6aPaAhWGsFQKHZBZDtMQ_AUICigB

- ↑ Nairobi Planning Innovations. Vision for Nairobi. Available at: https://nairobiplanninginnovations.com/nairobi-metro-2030/

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |