Course:GEOG352/Manila and Gentrification

Introduction

Gentrification

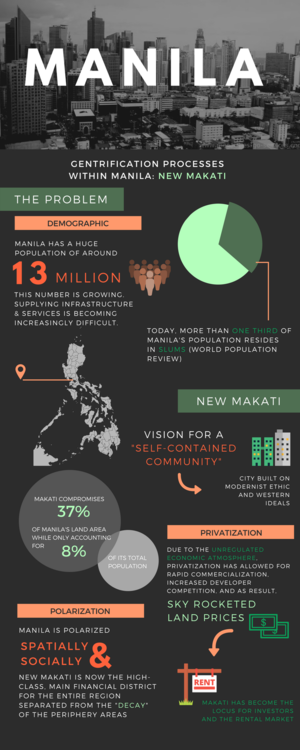

While the world's population continues to grow, cities and urban spaces are adapting and transforming rapidly as a result of the increase in people moving towards megacities. Megacities are becoming the main epicenters of globalization practices and modernity experimentation, and sustainable development is more important than ever as the key to the growth of these cities [1]. A prominent consequence of the massive growth of cities is gentrification, a process motivated by investment and growth that can displace people or whole communities. While the physical cores of megacities are reconstructed and renovated, the previous inhabitants are removed and pushed to the periphery. Gentrification encompasses politics, economics, and in many cases neoliberal practice while contextualizing itself within greater international, political, economic and social atmospheres. Gentrification is a matter of power and economic-driven development which often tends to be unequal, preventing people from access to basic services and rights. Gentrification takes on various forms in the global north and global south, depending on factors such as location and situation; therefore, the implications of gentrification in one city could vary with another. A prime example of gentrification in megacities is the city of Metro Manila, with its unprecedented population growth and constant urban expansion. Massive growth in Manila's urban population is pressuring massive urban renewal projects that accommodate a select wealthy class who can afford to pay the rising property costs and stay centrally located in the city. Cumulatively, gentrification processes are causing immense displacement for the lower-class urban inhabitants that used to live in these modernizing areas. Facing continued housing problems, the government needs to act soon or problems may grow out of the control for the national government to intervene and find a solution.

Overview of The Issue

A prime example of gentrification takes place in the city of Metro Manila, with its unprecedented population growth and constant urban expansion. Currently, Manila has approximately 16 million inhabitants with this number continuously increasing as more people are attracted to the city for work opportunities and anticipation of a better quality of living. [2] The spike in population is pressuring massive urban renewal and development. Moving with a neoliberal wave throughout the globe, there has been a bridged transformation from state-run policy and social structure to an unregulated economic atmosphere marketing itself for privatization. This process is causing immense displacement for the lower-class urban inhabitants that were living in the area, one of the many characteristics of gentrification.

Historical Context

By the 1990’s, land prices in the central business districts (CBDs) of Manila were increasing by as much as fifty percent annually, therefore many of the urban poor had to turn to informal settlements. There have been innovative practices to try and aid a bridge between this disconnect within the city, but displacement is still hugely impacted by these gentrification processes in Manila. [3] From 1521 to 1898, Metro Manila was reigned over by Spanish colonials whom initially granted traditional communal land in Metro Manila to friars but later-on became private estates with ownership concentrated within the hands of a few individuals.[4]

Land in Manila has continued to be in the hands of select groups and people and as early as 1939 a modernist ethic was developed when President Manuel Quezon began purchasing land outside the city to relocate informal dwellers. This was an attempt to leave the central urban areas of the city for private infrastructure and development investments. This process of selling and buying land rights is what ultimately led to the gentrification of regularized settlements from the beginning. [5]

Present Day Manila

A growing trend in Manila’s development today is that the local and national government is choosing to ignore the growing affects market dynamics are having on the informal settlers of Manila. For a city that has over 40% of its inhabitants residing in informal settlements, the need to provide land tenure security is vital in securing housing for one of Manila’s most vital classes of people [6]. The biggest problem contributing to Manila’s informal housing problems today is the continued rise in Manila's efforts to become a globalized city of economic wealth. 88% of Manila's manufacturing today is oriented towards global exports Specifically, Manila’s drive to expand its industrial regions like the CALABARZON region (comprising the districts of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon) and continuing to support corporate investment in Manila through the construction of CBDs like Makati that proving detrimental to the entirety of Metro Manila’s service sector inhabitants [7]. While Manila strives to accommodate and attract wealthy business professionals into the central locations of the city, it has resulted in increased real estate price hikes that are making housing unaffordable for many low-wage earners in Manila, therefore making land tenure difficult to achieve [8]. With a growing occupation of the central areas of the city by wealthy business classes this has resulted in the continued eviction of the informal settlers to the surrounding areas outside the main city and is posing a threat to the teachers, taxi drivers, factory workers, and vendors who rely on a close proximity to the city for work and income [9].

Metro Manila is unique in comparison to other urban centers of Asia because it is dominated by private development of the inner city for modernized growth[10]. CBD's, like Makati, are products of corrupt zoning processes that benefit private investors while working outside any governmental restrictions or management. These vast districts form the city's spatial and economic structure since they have the highest land values, and therefore dominate the land market while forming the city's overall geography.

Today, Manila is divided into sixteen city districts that are mainly private business districts. Each district has its own autonomous local governments that override national governmental jurisdiction like the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority [11]. Private investment has allowed for rapid commercialization of land that has skyrocketed prices and increased developer competition. Coupled with a shortage of available land, increasing poverty, increasing population densities, and the inability of the government to respond to the land and housing needs, it has left the majority of the urban poor to live under a constant threat of eviction. Despite this, eviction often is delayed due to government tolerance of informal occupation of public land, or private actors who wait to capitalize on land appreciation and illegally rent these spaces to informal settlers[12]. Nevertheless, Filipino political groups continue to strive for global economic development for capital growth at the cost of increasing taxes and government agencies that could be put in place to deal with informal housing problems and social welfare services that are so desperately needed [13]. With such vast processes of gentrification and private development in Metro Manila, it is helpful to analyze just one of these gentrifying districts of Manila selectively.

.

Detailed Case Study

Due to Manila’s size as an emerging global city, the rapid reinvention of city districts is a frequent occurrence. To become attractive for investment, districts often focus on improving rental markets, or financial business districts to bring in new international companies and workers. New Makati, a large district within Manila, has manifested itself as the epitome of investment and seclusion in the city, revealing the evidence of gentrification developing within the city.

Old Makati

The 1950’s marked the beginning of New Makati’s development under the Ayala family, who today, own more than half of the land in New Makati and dictate many of its future developments.[14]

The Ayala Corporation is the country's oldest and largest conglomerate that set the tone for the rest of the cities development. Old Makati was a city owned by the corporation that was notoriously known as a third-class municipality offering licentious entertainment such as gambling, prostitution, and cockfighting [15]. However, after the devastation of the American bombings on Manila due to Japanese occupiers in World War II, significant damage prompted the wealthy to move outside the city. This migration sparked great demographic shifts and presented the Ayala family with an opportunity for reinvention. This reinvention consisted of a modernist ethic when it came to the development of the New Makati City.[16]

Under the leadership of Joseph McMicking, the company embarked on building out their vision of a ‘self-contained community’ with a modern vision of urbanized mixed land use contracts for residential, commercial and industrial districts.[17] This type of development and enclosures created spaces specifically for the upper class, contrasting the original population of the middle class and urban poor. As Makati began to develop it became a locus for investors and the rental market and development continued under private projects. Forbes Park and Bel-Air Village are examples of famous up-market residential subdivisions created during this time.

New Makati

Proposed as a solution to Manila’s failure to become modernised, the urban vision of New Makati was for it to mark the progress that would solve the ‘problem’ of Manila by embodying the highest standards of development.[18] Though Western planning ideals are applied, they are largely irrelevant and illogical for the context of Metro Manila. Western concepts of ‘new urbanism’ or ‘smart growth planning’ -- which promote compact, high density, pedestrian/transit oriented mixed-use communities, have been used as application models, however, these urban Western concepts are based on significantly lower densities and populations, therefore ill-fitting for a city like Manila.[19]

New Makati today, has transformed into an area uniformly inhabited by the rich and expatriates, “separated from the decay and deficiency of the rest of the city” [4]; alternatively, a space of exclusivity from the urban poor. New Makati’s original plan as a space for middle and low-income workers has vastly shifted and the city has transformed into a high-class, privately developed, central businesses district. Makati compromises 37% of Manila’s land area while only accounting for 8% of its population.[20] The city overtime has transformed itself from a heterogeneous community with diverse socio-economic backgrounds to an area uniformly inhabited by the rich and expatriates.[21] The city is highly polarized both spatially and socially, and the central business district is separated from the decay of the rest of the peripheral city.[22] It was found in a city study that the quality of life in Makati is more similar to the quality of life in Japan, and the city has the most developed telecommunications infrastructure in the county.[23]

PricewaterhouseCooper's (PWC) "Emerging trends in real estate" study found that Manila ranked 12th out of 22 regional markets concerning investment prospects and second only to Jakarta in the secondary or rental apartment segment for 2013.[24] In 2017 this rank rose to 3rd out of 22 regional markets for prospective development.[25] With growing investment prospects this becomes evident in the massive investment in high-rise condominium development. With such a successful and profitable area for private investment, there is little incentive for Makati’s local government to try and halt growth in their business sectors to address issues of informal settlement and eviction processes. Interestingly, the annual public expenditure for housing in the Philippines, which accounts for roughly 1 percent of the total government expenditures, accounts for only 0.1 percent of GDP, which is one of the lowest in Asia. [26] Therefore, it is not the government that is paying for any of the housing developments in the country, but private investors largely. While the government does threaten to provide incentives to private builders to focus on building more housing for the informal populations, the lack of real estate available in the city for this as well as the lack of institutional financing by the government makes these policies ineffective. [27]

Solutions ?

With failing political initiatives by the government, new development plans have been proposed to address the stark contrasts that exist between districts like New Makati and the informal settlements that encompass the urban fringe. The Philippines Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council (HUDCC) which is a jurisdiction under the Offices of the President had published a Development plan on Shelter in 2011 that proposed changes to address informal settlement issues. These changes included, “(a) supporting other forms or modalities of security of tenure such as usufruct and lease rights; (b) developing PPPs for onsite upgrading and resettlement; (c) stimulating housing microfinance for end-user financing; and (d) strengthening community partnerships and stakeholdership through capacity development. Through the PPPs, urban renewal shall also be promoted for sustainable urban development, to ensure the balanced provision of revitalized infrastructure that would support social sectors, including socialized housing.”[28] Time will tell if these initiatives will prove successful in any capacity, but in the meantime CBD’s like New Makati continue to develop, evict, and gentrify surrounding areas of Manila, continuing to exacerbate housing problems in the Philippines.

Lessons Learned

Analyzing the discourse and contexts of Metro Manila and New Makati have raised some issues for this group's research. Much of the evidence provided in this work and by scholars that we have cited continues to focus heavily on policy and private urban developments that have taken place in Manila. Without any substantial talk of the informal and urban poor in the city, this has created a gap in the dialogue and ignores the largest and most important demographics of the city. What this wiki project has provided is a general sense that Metro Manila is unique in its context of privatized land development and a hands-off approach by the state government. Like any case study, New Makati and Manila have developed over a unique history of political change, population change, and changing megacity dynamics. Although these things are unique, larger dialogues of gentrification, privatization, globalization and urban informality are everyday issues relating to many cities in the global South. Additionally, Metro Manila's continued drive towards imitating northern cities and western ideals in their physical construction of city space is concerning because of the effects it is having on informal settlers, as well as the lack of geographical space need to implement western type infrastructure policies. In discussion with other global south cities on the rise, like Jakarta, we think that Metro Manila is a clear example of what other south Asian and Middle Eastern cities could become if private, unregulated, development is allowed to continue in these cities. Most importantly, Metro Manila highlights a need to focus more academic and political attention towards rapidly growing cities like Manila that continue to change and innovate despite the persistent social, economic, and political problems that create hurdles for positive development. By understanding gentrification in Manila, it begins to delve beyond the flashy and modern facades of CBDs like New Makati and it addresses what these modern districts are doing for the millions of people who face informal status and housing security issues. In doing so, it highlights areas where change needs to happen to meet future demands of the cities growing inhabitants and ensure a positive and equitable growth model of future development for this global megacity.

References

- ↑ Kraas, F., M. Coy, and S. Aggarwal. (2014). Megacities: Our Global Urban Future. Springer, New York. http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789048134168

- ↑ Michel, Boris. (2010). "Going Global, Veiling the Poor Global City Imaginaries in Metro Manila." Philippine Studies, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 383-406. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=403442075296567;res=IELIND

- ↑ Mercado, R.M. (2016). "People's Risk Perceptions and Responses to Climate Change and Natural Disasters in BASECO Compound, Manila, Philippines", Procedia Environmental Sciences, vol. 34, pp. 490-505. https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S1878029616300652

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Choi, N. (2016). "Metro Manila through the gentrification lens: Disparities in urban planning and displacement risks.” Urban Studies, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 577-592.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042098014543032 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "”Choi”" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Porio, E. & Crisol, C. (2004). "Property rights, security of tenure and the urban poor in Metro Manila", Habitat International, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 203-219. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197397503000687

- ↑ Shatkin, G. 2004, "Planning to Forget: Informal Settlements as 'Forgotten Places' in Globalising Metro Manila", Urban Studies, vol. 41, no. 12, pp. 2469. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00420980412331297636

- ↑ Ibid, 2473.

- ↑ Ibid, 2471.

- ↑ Ibid, 2469.

- ↑ Corpuz, Arturo. (2013). “Land Use Policy Impacts on Human Development in the Philippines.” Human Development Network. pp, 1-19.

- ↑ MMDA. http://www.mmda.gov.ph/

- ↑ Shatkin, 2474.

- ↑ Ibid, 2476-2477.

- ↑ ibid, 3.

- ↑ Garrido, Marco. (2012). “The Ideology of the Dual City: The Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila.” International Journal or Urban and Regional Research, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 165-185. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01100.x

- ↑ ibid, 7.

- ↑ ibid, 7.

- ↑ ibid, 7.

- ↑ ibid, 5.

- ↑ ibid, 7.

- ↑ ibid, 3.

- ↑ ibid, 3.

- ↑ ibid, 7.

- ↑ Choi, 583.

- ↑ PWC. 2018. “Emerging Trends in Real Estate.” https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/financial-services/asset-management/emerging-trends-real-estate/global-outlook-2018.html

- ↑ Hudcc.gov.ph. (2011). Philippine Development Plan on Shelter. pg. 4. [online] Available at: http://www.hudcc.gov.ph/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/document/PHILIPPINE%20DEVELOPMENT%20PLAN.pdf [Accessed 7 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ ibid, 5.

- ↑ ibid, 8.