Course:GEOG352/Environmental Impacts of Internal Migration to Dhaka

Introduction: Urbanization and Rural to Urban Migration in the Global South

More people live in cities now than ever before in human history. As of 2016, 54.5 percent of the world’s population live in cities.[1] In 2014, the United Nations projected that “66 percent of the world’s population” will be urban by 2050.[2] Most of the world’s megacities, with a population of 10 million or more, are located in the global south.[3] Megacities are rapidly growing and are projected to house 730 million people by 2030, which will represent “8.7 per cent of people globally”.[4] It is important to recognize that these megacities are not expanding, developing and existing in isolation, as Parag Khanna argues, you cannot calculate the individual value of a megacity without “understanding the role of the flow of people, finance, and technology that enable them to thrive”[5]. Migratory flows, within cities, between cities and between cities and their surroundings are incredibly important to help us understand the growth of a city. One such flow is rural to urban migration (referred to as RUM in the rest of the wiki), which involves the permanent or semi permanent “movement of people from rural areas into cities,” is a major “socioeconomic phenomenon and a spatial process” experienced predominantly in the Global South.[6] RUM has been a major driver for rapid urbanization in the Global South as migrants are moving into cities at ever growing rates.[7] As urban populations grow and cities expand, there is enormous strain on infrastructure due to the ever growing needs of the rising urban populations. Although megacities do not house the majority of the urban population, they are especially vulnerable to these challenges due to their very larger populations.[8] One particularly salient example of a city dealing with RUM and its impacts is Dhaka, the capital city and a major urban centre of Bangladesh.

Overview: Dhaka and Rural to Urban Migration

Dhaka: Urbanization and Rural to Urban Migration

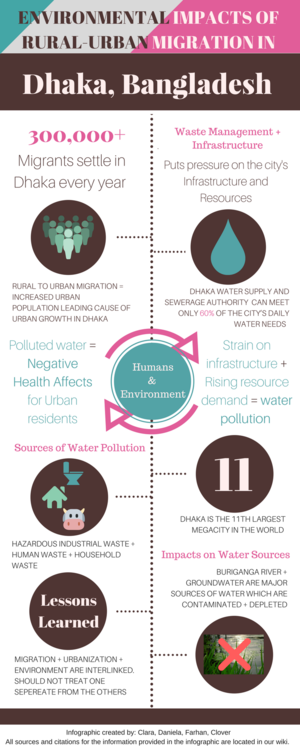

With rapidly urbanizing cities in lower-middle-income countries as the places where “sustainable development challenges” are the most prevalent, it is clear that Dhaka is an important city in which to explore the environmental impacts of migration.[9] Dhaka has one of the highest urban population growth rates in the world and is the 11th largest megacity.[10] Dhaka is undergoing a massive influx of rural to urban migrants, which is the predominant cause for this growth. Dhaka’s population has risen exponentially from half a million people in 1965 to more than 12 million in 2006.[11] According to the World Bank, with roughly 300,000 to 400,000 migrants arriving every year, Dhaka has the "the highest population growth in the world."[12] Furthermore, Dhaka’s population density has increased significantly at a rate of 3.72% per year and the city now has more than 23,000 people living per square kilometer.[13] This increase in migration to the city is due to a number of push (e.g. severe and frequent natural disasters, poverty, unemployment, landlessness, absence of industries, homelessness) and pull factors (e.g. economic opportunities, ease of access to the informal sector, “[r]ural urban disparities in social amenities and services”).[14] These push and pull factors are centred around the lack of social, economic and cultural opportunities in rural Bangladesh for these individuals.The rapid urbanization has been unplanned and has caused a number of changes to the city, including negative environmental impacts.[15]

Consequences of Rural to Urban Migration

This growth phenomenon exceeds the rate of urban development in Dhaka, putting a huge strain on the city’s ability to allocate enough resources for the newly arrived migrants. Dhaka, like many other cities affected by RUM, is struggling to keep up with the demands of the growing population on resources and infrastructure to provide basic civic amenities (e.g. water, waste management, electricity). For example, the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA) can meet only 60% of the city’s daily water needs, and the shortage is increasing everyday as more migrants come to the city.[16] The enormous strain on existing infrastructure leads to adverse environmental effects, such as human and industrial waste from the growing number of factories employing RUM migrants, polluting rivers nearby.[17] The polluted water in turn impacts the health of the RUM migrants, many of which live in slums. Roughly 28 percent of Dhaka’s population is living in poverty, and of those 28 percent, an estimated 47.5 percent of them live in slums and squatter settlements.[18] It is important to recognize the cyclical and reciprocal aspect of human and nature interactions and impacts, which will be explored in more detail in the below case study on water pollution in Dhaka.

Case Study

The process of rural to urban migration in Dhaka is intertwined in a number of other processes of urbanization that take place in the city. However, the city has developed haphazardly without considering the manner in which these processes react to and with each other. The outcome of this form of development is a detrimental and perpetual harm of the natural environment, which in turn has had a direct impact on the urban population of Dhaka. In spite of the many issues that have risen from this influx of rural migrants to Dhaka, this case study focuses specifically on the contamination of water sources and the pollution from household and industrial waste that takes place, due to the rudimentary waste management processes that exist in the city.

Sources of Water Pollution

Like Dhaka’s population, the household and industrial waste in the city has also increased exponentially. Industrial areas have expanded in relation to the supply of labour that migrants offer, thus generating larger outputs of waste. This is explained as a positive feedback loop in which more migrants move to the city because they are lured by a higher demand for labour in industrial areas. Simultaneously, industrial areas grow in response to the number of migrants that arrive searching for employment.[19] The industrial areas in the city such as Tejgaon and Tongi are home to a vast number of factories producing garment related goods such as textile dyeing. However, there is also a significant presence of factories producing detergents, dry cell batteries, pharmaceuticals, and other chemical products.[20] The Hazaribagh area near the Buriganga river is home to over 40 tanneries, located in just 25 hectares of land. Most of these tanneries are more than 35 years old and discharge about 6000 cubic metres of liquid waste containing carcinogenic chemicals such as hexavalent chromium, and 10 tons of untreated solid waste every day.[21] Hazardous, solid and water waste from these various industries is not treated at the source, and is illegally dumped into the various water bodies around Dhaka city. Household waste is also increasing at an exponential rate with the population. Contrary to the industrial synthetic waste, the household waste in Dhaka is almost 70% - 80% organic.[22] Even though much of this organic waste has the potential to be composted or used for bio-energy, much of this is dumped without treatment. During the summer season, when fruit production is at its highest, households in Dhaka produce up to 3500 tons of organic waste per day. In informal settlements such as the slums where the vast majority of the migrants live, the problem is even more acute as household garbage, liquid waste from kitchens and washing is randomly discharged nearby on site.

Waste Management and Infrastructure

It is estimated that 3.4 million people in Dhaka city live in slums.[23] However, out of that 3.4 million, only 9% of the slum population is provided with solid waste management services by the main municipal governing body, The Dhaka City Corporation.[24] Most of the slum population discards waste in public spaces, unused land, and nearby water bodies. Alongside, there is no central sewage collection infrastructure in Dhaka city to handle the liquid waste from slums, urban households, and industries. There also is a lack of regulation and formal municipal processes to handle liquid and solid waste in a sustainable and sanitary way. Around 30% of Dhaka’s population uses septic tanks, and a significant population in the informal areas use bucket and pit latrines.[25] In areas where sewage system exists, lack of repair and poor maintenance lead to sewage overflow into storm drains. The lack of infrastructure and systematic waste management structure lead to people adopting arbitrary waste disposal methods that lead to pollution of the rivers, water bodies around the city, and contaminate quintessential groundwater and surface water sources.

Impact on Water Sources

The combined effect of inadequate infrastructure and the increase in water polluting effluents from households and industry generates a dangerous environment for the urban population of Dhaka. Studies show that factories in industrial sectors are the main sources of heavy metal pollution, as they discharge unsafe levels of copper, iron, and cadmium in various water systems in southwestern Dhaka.[26] Additionally, it has been demonstrated on a number of occasions that surface water sources throughout Bangladesh are heavily contaminated with faecal coliforms and by various pathogenic bacteria.[27] Contaminated drinking water is either ingested or comes into contact with humans through the household use of this water, especially after post-flood periods. During heavy rain and monsoon seasons, there is an increased risk of overflow of stormwater drains, which are clogged by solid waste. This is a danger that slum dwellers in low-lying areas face annually and it has lead to concerning outbreaks of diarrhea, as well as other gastrointestinal infections and diseases.[28] “Due to a poor drainage system stormwater forms large pools that become breeding sites for mosquitoes which are the cause of malaria and dengue fever.”[29] Those living nearest to garbage dump sites, have been reported to suffer from skin irritation, respiratory and sight ailments, and having a higher risk of contracting diseases.[30]

The pollution of water sources is a dire problem given the fact that the Buriganga river and other stagnant water bodies provide for nearly half of the city’s daily water needs. This is the case given that only 40% of water demand is met by the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA) and the shortage is increasing every day as more migrants come to the city.[31] Dhaka has relied on much of its groundwater supply and is depleting fast due to low recharge and over-exploitation.[32] As a result, the natural state of the Buriganga River and other water systems in the city have been altered in terms of their physical, chemical and microbiological composition. In the process, their suitability has been rendered unusable because of the human consequences they provoke. Some manifestations of the contaminated water sources include bad taste, offensive odours, unchecked growth of aquatic weeds, and a decrease in the number of aquatic animals, floating of oil and grease, and unnatural colouration of water.[33] By being subject to increased waste exposure and having no sanitation facilities, environmental pollution is having a direct impact on migrants.

Lessons Learned from Dhaka's Case Study

What became evident through the case study of Dhaka is that migration, urbanization, and ecological concerns are all intrinsically tied together. What is less focused on in this case study, but is equally important is the need for balance between- meeting the needs of the environment, and of incoming migrants. For example, there is a need to make sure that slum dwellers, migrants, people of lower economic status, and people who are the most vulnerable in society are able to meet their basic resource needs (e.g. clean safe drinking water, paper waste management) safely and efficiently. What authorities also need to ensure is that the strategies put forward to address the infrastructural and resource needs of these growing urban populations take the environment into account, and do not further harm the environment. These would include projects to, for example, provide clean safe drinking water to slum dwellers in Dhaka by expanding the city's infrastructure. In order to be viable in the long run, these solutions and strategies need to be sustainable (i.e. balancing social, economic, and environmental needs). Other cities in the global south, such as Beijing, China, face similar urbanization, migration and thus environmental concerns (e.g. air pollution). These other megacities can take lessons from this case study on Dhaka and the importance of the environment. The environment is not simply a backdrop for social, economic, and cultural activities and interactions. The environment has a huge impact on human lives, just as humans have a huge impact on the environment. The case study focused on how the water pollution and contamination produced by increase in migrant population in Dhaka (e.g. industrial, human waste) contributes to increased pollution, water contamination, water borne diseases, and other adverse health effects for the population. This is a perfect illustration of the cyclical nature of the human-nature relationship of cities and the need for cities to adopt better policies for environmental sustainability.

References

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2016). The World’s Cities in 2016 – Data Booklet. New York: United Nations, p. i-26. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018]. Wang, W. (2010). Rural-Urban Migration. In: B. Warf, ed., Encyclopedia of Geography. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., p. 2496-2498. Available at: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/geography/n1005.xml [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights. New York: United Nations, p. 1-27. Available at: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-highlights.pdf [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018]. Riana. (2007). Dhaka city. [image] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dhaka_city.jpg [Accessed 6 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2016). The World’s Cities in 2016 – Data Booklet. New York: United Nations, p. i-26. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018]. Wang, W. (2010). Rural-Urban Migration. In: B. Warf, ed., Encyclopedia of Geography. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., p. 2496-2498. Available at: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/geography/n1005.xml [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2016). The World’s Cities in 2016 – Data Booklet. New York: United Nations, p. i-26. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018]. Wang, W. (2010). Rural-Urban Migration. In: B. Warf, ed., Encyclopedia of Geography. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., p. 2496-2498. Available at: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/geography/n1005.xml [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Khanna, P. (2016). How megacities are changing the map of the world. [video] Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/parag_khanna_how_megacities_are_changing_the_map_of_the_world/transcript [Accessed 2 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ Wang, W. (2010). Rural-Urban Migration. In: B. Warf, ed., Encyclopedia of Geography. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., p. 2496-2498. Available at: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/geography/n1005.xml [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Ullah, A. A. (2004). Bright city lights and slums of dhaka city: Determinants of rural-urban migration in bangladesh. Migration Letters, [online] Volume 1(1), p. 26-41. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1268699765?pq-origsite=360link&accountid=14656 [Accessed 6 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2016). The World’s Cities in 2016 – Data Booklet. New York: United Nations, p. i-26. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights. New York: United Nations, p. 1-27. Available at: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-highlights.pdf [Accessed 30 Mar. 2018]. Riana. (2007). Dhaka city. [image] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dhaka_city.jpg [Accessed 6 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ The World Bank, (2015). South Asia Population: Urban Growth: A Challenge and an Opportunity. [online] Available at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/SOUTHASIAEXT/0,,contentMDK:21393869%7EpagePK:146736%7EpiPK:146830%7EtheSitePK:223547,00.html#example [Accessed 8 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Hossain, A. M. M. and Rahman, S. (2012). Impact of Land Use and Urbanization Activities on Water Quality of the Mega City, Dhaka. Asian Journal of Water, Environment and Pollution, [online] Volume 9(2), p.1-9. Available at: https://content.iospress.com/articles/asian-journal-of-water-environment-and-pollution/ajw9-2-02 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ The World Bank, (2015). South Asia Population: Urban Growth: A Challenge and an Opportunity. [online] Available at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/SOUTHASIAEXT/0,,contentMDK:21393869%7EpagePK:146736%7EpiPK:146830%7EtheSitePK:223547,00.html#example [Accessed 8 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Parvin, M. and Begum, A. (2018). Organic Solid Waste Management and the Urban Poor in Dhaka City. International Journal of Waste Resources, [online] Volume 8, p. 1-9. Available at: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/organic-solid-waste-management-and-the-urban-poor-in-dhaka-city-2252-5211-1000320.pdf [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Momtaz, J. (2012). Impact of rural urban migration on physical and social environment: The case of Dhaka city. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, [online] Volume 1(2), p. 186-194. Available at: https://doaj.org/article/f91c35d8645646b9804d7a42edf06d92 [Accessed 18 Jan. 2018].

- ↑ Momtaz, S. and Zobaidul, S. K. (2014). Environmental Problems and Governance. In: A. Dewan and R. Corner, eds., Dhaka Megacity: Geospatial Perspectives on Urbanisation, Environment and Health, 1st ed. [ebook] Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 283-299. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-94-007-6735-5 [Accessed 29 Jan. 2018].

- ↑ Khan, H. R. and Siddique, Q. I. (2000). Urban water management problems in developing countries with particular reference to Bangladesh. International Journal of water resources development, [online] Volume 16(1), p. 21-33. Available at: http://iahr.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07900620048545#.WoeOhGYZOt8 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Mahbubur Rahman, M., Hassan, M. S., Bahauddin, K., Khondoker Ratul, A., & Hossain Bhuiyan, M. A. (2017). Exploring the impact of rural–urban migration on urban land use and land cover: a case of Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Migration and Development, p. 1-18. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21632324.2017.1301298 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ The World Bank, (2015). South Asia Population: Urban Growth: A Challenge and an Opportunity. [online] Available at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/SOUTHASIAEXT/0,,contentMDK:21393869%7EpagePK:146736%7EpiPK:146830%7EtheSitePK:223547,00.html#example [Accessed 8 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Ullah, A. A. (2004). Bright city lights and slums of dhaka city: Determinants of rural-urban migration in bangladesh. Migration Letters, [online] Volume 1(1), p. 26-41. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1268699765?pq-origsite=360link&accountid=14656 [Accessed 6 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ Azharul Haq, K., (2006). Water management in Dhaka. Water Resources Development, 22(2), pp. 291-311. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07900620600677810 [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Maurice, J. (2001). Tannery pollution threatens health of half-million Bangladesh residents. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, [online] Volume 79(1), p. 78-79. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/229546798?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14656 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Parvin, M. and Begum, A. (2018). Organic Solid Waste Management and the Urban Poor in Dhaka City. International Journal of Waste Resources, [online] Volume 8, p. 1-9. Available at: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/organic-solid-waste-management-and-the-urban-poor-in-dhaka-city-2252-5211-1000320.pdf [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Gruebner, O., Khan, M. M. H., Lautenbach, S., Müller, D., Krämer, A., Lakes, T. and Hostert, P. (2012). Mental health in the slums of Dhaka-a geoepidemiological study. BMC Public Health, [online] Volume 12(1), p. 177. Available at: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-12-177 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Momtaz, J. (2012). Impact of rural urban migration on physical and social environment: The case of Dhaka city. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, [online] Volume 1(2), p. 186-194. Available at: https://doaj.org/article/f91c35d8645646b9804d7a42edf06d92 [Accessed 18 Jan. 2018].

- ↑ Azharul Haq, K., (2006). Water management in Dhaka. Water Resources Development, 22(2), pp. 291-311. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07900620600677810 [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ Ahmad, J. U, and Goni, M. A. (2016). Heavy metal contamination in water, soil, and vegetables of the industrial areas in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, [online] Volume 166(1), p. 347-357. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/519825534?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14656 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Sirajul Islam, M., Brooks, A., Kabir, M.S., Jahid, I.K., Shafiqul Islam, M., Goswami, D., Nair, G.B., Larson, C., Yukiko, W. and Luby, S. (2007). Faecal contamination of drinking water sources of Dhaka city during the 2004 flood in Bangladesh and use of disinfectants for water treatment. Journal of applied microbiology, [online] Volume 103(1), p. 80-87. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03234.x [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Sirajul Islam, M., Brooks, A., Kabir, M.S., Jahid, I.K., Shafiqul Islam, M., Goswami, D., Nair, G.B., Larson, C., Yukiko, W. and Luby, S. (2007). Faecal contamination of drinking water sources of Dhaka city during the 2004 flood in Bangladesh and use of disinfectants for water treatment. Journal of applied microbiology, [online] Volume 103(1), p. 80-87. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03234.x [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Mahbubur Rahman, M., Hassan, M. S., Bahauddin, K., Khondoker Ratul, A., & Hossain Bhuiyan, M. A. (2017). Exploring the impact of rural–urban migration on urban land use and land cover: a case of Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Migration and Development, p. 1-18. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21632324.2017.1301298 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Parvin, M. and Begum, A. (2018). Organic Solid Waste Management and the Urban Poor in Dhaka City. International Journal of Waste Resources, [online] Volume 8, p. 1-9. Available at: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/organic-solid-waste-management-and-the-urban-poor-in-dhaka-city-2252-5211-1000320.pdf [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Khan, H. R. and Siddique, Q. I. (2000). Urban water management problems in developing countries with particular reference to Bangladesh. International Journal of water resources development, [online] Volume 16(1), p. 21-33. Available at: http://iahr.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07900620048545#.WoeOhGYZOt8 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Nahar, M. S., Zhang, J., Ueda, A., & Yoshihisa, F. (2014). Investigation of severe water problem in urban areas of a developing country: The case of dhaka, bangladesh. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, [online] Volume 36(6), p. 1079-94. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10653-014-9616-5 [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ Sirajul Islam, M., Brooks, A., Kabir, M.S., Jahid, I.K., Shafiqul Islam, M., Goswami, D., Nair, G.B., Larson, C., Yukiko, W. and Luby, S. (2007). Faecal contamination of drinking water sources of Dhaka city during the 2004 flood in Bangladesh and use of disinfectants for water treatment. Journal of applied microbiology, [online] Volume 103(1), p. 80-87. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03234.x [Accessed 16 Feb. 2018].

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |