Course:GEOG352/Critical Urban Theory in Johannesburg

The vast gold reserve of South Africa attracted the interests of Europeans and prompted the set-up base in the Southern-most nation of Africa. With colonial rule began a campaign of racial superiority throughout the continent. The many Westerners living in South Africa during the 20th century became wealthy land and business owners while local populations perished, mostly, as workers. Entrenched in long-standing racial rivalries, all aspects of daily living were subject to these discriminatory practices. As these policies came to fore in the 1940s, they continue to plague cities within South Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa’s largest city, which boasts a population of about 4.4 million, is no different. The city’s geography showcases the racially motivated policies that were implemented to physically, through space, separate people along racial lines. Not only did these policies carve up the cities’ residential areas racially, the implemented policies have continued to have social, political and economic impacts along racial lines. Entrenched in long-standing racial rivalries, we opted to look at post-colonial Johannesburg through the lens of segregation policies and the consequent racial spatial patterns that developed. To exemplify our claim, we focus our research on the case of Soweto, the South Western townships, to assess the impact of the colonial structures and institutions. Focusing largely on healthcare, we bring forth the effects of these discriminatory practices - in using physical space as a means of racial divide, the presence of, which still is prevalent in many South African cities.

Overview

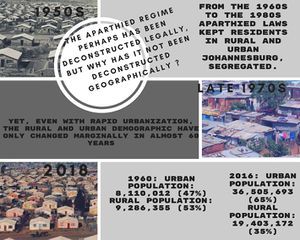

Post-colonial theory is integral to the context of Johannesburg, South Africa because spatial segregation remains a defining characteristic of the city. The complexities of modernization for African states emerge from the colonial experience [1](Ahluwalia 2001). As a result, colonialism in the city defined space not only during the apartheid era but continues to dictate the city’s use of space today. While we must recognize the extent of colonialism in the city, it is also vital to acknowledge that its problematic to centralize colonialism as the “principle of structuration” in history “so that all that came before colonialism becomes its own prehistory and whatever comes after can only be lived as infinite aftermath” [1](Ahluwalia 2001). While recognizing that colonialism played a role in shaping the city, it cannot be seen as the sole contributor. Nevertheless, as apartheid was a major determinant of space in the country, it is difficult to look beyond it to understand spatial segregation today. In addition, the problem of having one “authentic African input” into the use and definition of space is problematic [1](Ahluwalia 2001). As South African’s desires vary across gender, class and cultural lines in addition to racial lines, it is difficult to present one unified voice of post-colonial theory. Since colonialism left legacies of “multiple identities”, it may be “necessary to forge a unified identity” for nation-building moving forward [1](Ahluwalia 2001). Yet arriving at a unified consensus on a theory is especially difficult when space so clearly divides the wealthier white residents of the city and the often poorer, black residents, in both the history of the city and the power relations that are still pertinent today. While it is difficult to arrive at a post-colonial theory for Johannesburg, it nevertheless uncovers the power relations that shape the conceptualization of the world [1](Ahluwalia 2001). While class remains a prominent part of community space in Johannesburg, the racial makeup of neighborhoods is changing. With the institutionalization of apartheid in 1948 and the consequent legislation implementation, Johannesburg witnessed a large-scale racial segregation program to preserve the white political and economic domination over South Africa [2](Peters 2004). Originating from the Afrikaans word for ‘separateness’ [3](Peters 2004), apartheid laid the legal foundation for urban racial zoning through residential segregation. Government enforced plans carved Johannesburg’s residential areas. The division is primarily “into the northern neighbourhoods, which are mostly White and middle-class, and the southern neighbourhoods, which are mostly Black and working-class”[4](Crankshaw 2008). Today, the traditionally white neighbourhoods are the location of cultural hubs of "offices, shopping malls, manufacturing parks and recreation facilities in the form of cinemas, restaurants and sports centres" [5](Crankshaw 2008). Consequently, these northern neighborhoods are where a majority of high earning individuals reside [6](Crankshaw 2008). These segregationist policies, implemented late 1940s/early 1950s, continue to play a role in Johannesburg. Wealthier suburb neighborhoods are no longer exclusively white, with "substantial desegregation by a black middle class", especially those who are homeowners [7](Crankshaw 2008). As such, the “racially exclusive character of middle-class neighbourhoods is in widespread decline” and the city is perhaps moving to a segregation based on class, rather than race[8] (Crankshaw 2008). The impact of land segregation is not uniquely a South African problem. While apartheid does differentiate the city, racial policies that divide neighbourhoods are not exclusive to Johannesburg. As such, impacts of colonialism and the subsequent critical urban theories have been applied to various countries in the African context. Nevertheless, it is important that although the city is not unique for facing these problems of land and space in post-colonial theory, it is different from other cities and cannot be drawn as a direct comparison given its unique history.

Case Study of Theme

Soweto’s History

Soweto’s close to a million population is for the most part black, including a substantial gangster population and numerous illegal inhabitants from Zimbabwe and Mozambique [9](Ncala 1981), with 98.54% of the aggregate population compromising of Black, trailed by Whites of 0.12%, and Asians at 0.10% (Crais et al. 2013). In 1978, black people gained the right to occupy land for residential, business, or professional purposes [10](Ncala 1981), and then in 1983 the town moved from being managed by the Johannesburg board to selecting its own specific black councillors, as per the Black Local Authorities Act [11](Crais et al. 2013). The Education and Training Act 90 of 1979 aimed at increasing literacy levels by providing free compulsory schooling, as low literacy levels were believed to lead to unemployment, poverty, and ill health [12](Ncala 1981), but with a lack of resources such as efficient medical practices, support groups, and sanitary living conditions, Soweto struggled with an increase in rape, abuse of drugs, murder, and theft due to the town’s populations’ battles with liquor abuse [13](Ncala 1981). Many in Soweto were contracting HIV, and the level of HIV infections in the adult population rose from 1% in 1990 to more than 20% in 2000 [14](Ncala 1981), with those who are poor and subjected to live in Soweto and other townships due to the segregationist planning of British colonialism being systematically stuck with poor health services.

The Soweto Uprising

With none of the state’s apartheid policies succeeding, and the homelands system receiving little support among black South Africans, the homelands were a disaster [15](Crais et al. 2013). South Africa’s economy relied on black labour, and wages were kept artificially low owing to racial laws and the prohibition of unionization [16](Crais et al. 2013), further suppressing Soweto’s population as low wages creates systematic segregation in poor urban areas causing the poor to stay poor, and the upper class to profit off of exploiting the lower class stunting their growth and “[warping] economic growth” [17](Crais et al. 2013). In 1976, an enormous uprising began as “students protested against the utilization of Afrikaans” [18](Crais et al. 2013) which was to be enforced by the government. This resulted in a massive movement taking place, leading to the Soweto Uprising - a massacre which took place on June 16 in Soweto followed by state persecution across the country [19](Crais et al. 2013). In 1969, university students created the South African Students Organisation partly in response to the white-dominated National Union of South African Students [20](Crais et al. 2013) which became critical to the development and spread of the Black Consciousness movement led by Steven Biko who died in 1977 from beatings received while in police custody. In early 1973, wildcat strikes spread throughout Durban [21](Crais et al. 2013) which comprised of underpaid African workers who were subjected to poor conditions and lack of rights, which led to the government soon legalizing black unionization [22](Crais et al. 2013). These successes helped foster the idea that black people do have rights, and that in creating collective, political movements they can help reshape governance and create a better future in Soweto. This collective voice of the black peoples in Soweto’s uprising represented the full diversity of the black population. Those in middle and low classes, educated and uneducated, workers and students, the old and young gathered together as one movement with one goal - to exist.

Aftermath

The apartheid state started policies to reform township governance, which created a tricameral parliament in 1984 [23](Crais et al. 2013), which denied the vote to the majority of South Africans, led to widespread resistance and the formations of organizations such as the United Democratic Front, followed by an intensification of political repression that included the deployment of the army throughout the country’s black townships [24](Crais et al. 2013) leading to tens of thousands people dying due to violence, and many more ending up incarcerated. In 1989 under the new leadership, political prisoners were released and negotiations started to take place [25](Crais et al. 2013). Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings began in 1996, to re-assess the history in South Africa [26](Crais et al. 2013) which led to South Africa and areas of spatialized segregation to start a journey of healing, development, and opportunity out of apartheid. The movement was powerful as the black population fought for their right to live, and for a future that would hopefully remove the colonial system of power which systematically deconstructed African life. However, in Soweto’s case, the area has remained in poverty due to low income continuing, and a lack of infrastructure and funding to cope with its rising population and demands. The lack of resources continues to deprive the population of good health, job opportunities, and a chance to rise above the lower social classes and move out of Soweto. Whatever resources and services Johannesburg and its townships have such as public health spaces tend to only benefit the higher society - notably Caucasians - with private health spaces such as places of refuge, or the cemetery being an only option for the lower class - the African population.

Lessons Learned

The above-state argument showcases the outcomes of colonial discriminatory practices, which, through racial spatial segregation, pervades South African society. Soweto, our focus of study, is, and has been throughout colonial and post-independent history, subject to the prevalence of discriminatory legislation. Having gone through waves of protests, unionization attempts and endeavours to alleviate one-selves out of poverty, inequality and social injustice, Soweto, till date, faces problems of brunt of decades-long discriminatory legislation. Segregation, motivated by race and implemented through space, has devastated the lives of those that reside in the Soweto and other racially segregated spaces in Johannesburg, and the rest of South Africa.

Johannesburg is an ideal example to look at, through the post-colonial lens, the consequences of the colonial administrations and their implemented institutions - which, till date, affects a number of cities in the Global South that have been subject to imperialism. The creation and establishment of racial politics is not one that is limited to Johannesburg or even South Africa, it is prevalent almost throughout the Global South. Our focus, Johannesburg, showcases the need for transformation and reformation of rigid institutional colonial and post-colonial characteristics that hinder equality and social justice, even after decades of independent rule being achieved. Although overt racial discrimination has decreased over the years, it is still prevalent in urban societies across the Global South. What initially started as racial spatial discrimination, as we see in our case study, eventually evolves into distinct and inflexible class differences - something that has become rather characteristic of urban societies in the Global South. Much like the Soweto, a geographical region facing poverty, extreme inequalities in education, healthcare and other state services, we see how spatial geographic demarcation segregates the rich from the poor; the privileged from those exempt. Whether it be the Khayeltisha in Cape Town; Orangi Town of Karachi; or Dharavi in Mumbai - we can see how space and geographical regions are used as a means spatial segregation in the contexts of large urban cities. Therefore, Johannesburg is an ideal example of a city ravaged by spatial politics and the resultant discrimination that occurs from the prevalence of such institutions in large urban contexts in the Global South.

Reference List

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Ahluwalia, P., 2001. Politics and Post-Colonial Theory: African Inflections. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Peters, W. 2004, "Apartheid politics and architecture in South Africa", Social Identities, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 537-547.

- ↑ Peters, W. 2004, "Apartheid politics and architecture in South Africa", Social Identities, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 537-547.

- ↑ Crankshaw, O. 2008, "Race, Space and the Post-Fordist Spatial Order of Johannesburg", Urban Studies, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1692-1711.

- ↑ Crankshaw, O. 2008, "Race, Space and the Post-Fordist Spatial Order of Johannesburg", Urban Studies, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1692-1711.

- ↑ Crankshaw, O. 2008, "Race, Space and the Post-Fordist Spatial Order of Johannesburg", Urban Studies, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1692-1711.

- ↑ Crankshaw, O. 2008, "Race, Space and the Post-Fordist Spatial Order of Johannesburg", Urban Studies, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1692-1711.

- ↑ Crankshaw, O. 2008, "Race, Space and the Post-Fordist Spatial Order of Johannesburg", Urban Studies, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 1692-1711.

- ↑ Ncala, J.T. 1981, "A survey in Soweto (South Western Township) on the available health services", Curationis, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Ncala, J.T. 1981, "A survey in Soweto (South Western Township) on the available health services", Curationis, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Ncala, J.T. 1981, "A survey in Soweto (South Western Township) on the available health services", Curationis, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Ncala, J.T. 1981, "A survey in Soweto (South Western Township) on the available health services", Curationis, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Ncala, J.T. 1981, "A survey in Soweto (South Western Township) on the available health services", Curationis, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

- ↑ Crais, Clifton C., Thomas V. McClendon, and e-Duke Books Scholarly Collection 2013. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press, Durham, 2014;2013;.

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |