Course:GEOG352/2019/Water Scarcity in Cape Town

The rapid development of urban spaces in the geographical south and east pose unique challenges that cannot be resolved through northern development theory due to the rate of expansion that is taking place. Unchecked growth, following a hyper neoliberalism approach, fails to produce sustainable and viable urban centres. Urban expansion has the potential to cause irreversible effects on the surrounding environment, leading to changes in biodiversity, land-use cover, and hydrological systems [1]. Therefore, a sustainability lens must be adopted to analyze the rapid development of urban spaces. Sustainability stretches beyond environmental features; it can be understood as the interaction and entwinement of economic, social, and environmental sectors- lying at the intersection of the urban and the natural and exposing the subsequent consequences of poor resource management [2].

South Africa’s Cape Town continues to face confrontation due to environmental impacts and the consequences of poor resource management, forcing the implementation of innovative strategies to mitigate the effects of water scarcity. Social mobilization is increasingly being used as a means to address the implications of environmental resource scarcity among a growing population. A contextual understanding of these pressures allows for the examination of specific organic responses. However, it must be understood that the experiences of Cape Town will continue to be seen globally as a response to rapid urbanization and increasing environmental pressures causing stress on urban centres. The global phenomenon of resource scarcity is explored below, followed by the specific experiences of Cape Town- lending consideration to their innovative responses and the ways in which ‘Day Zero’ was avoided. Grounding the concepts of resource scarcity and sustainable development in an explicit urban context allows for tangible evidence of ways in which they are addressed.

Overview

In geographical locations that experience persistently high temperatures in any season, sustainable water management is essential to ensure the health and functioning of the population and built environment due to the increased risk of drought. Urban centres around the world can be characterized based upon their density; urban centres have a greater population density compared to rural settings [3]. Therefore, due to their greater population density, urban centres have higher demands for freshwater for purposes related to consumption, as well as infrastructural and agricultural uses. Irresponsible water management in areas prone to drought could risk a ‘water crisis’ [4], in which there may be limited access or not enough water for every citizen, along with inadequate supplies for the functioning of some industries.

Water Scarcity and Climate Change

The interaction of rapid urbanization paired with the looming consequences of climate change escalates the issue of water scarcity, leading to the justified panic among urban dwellers and non-urban dwellers alike. The growing threat of overusing valuable, scarce resources, such as water, in urban settings has become increasingly evident due to the observed impacts of climate change. Due to the current global response to the projected effects of climate change, we can expect climate related pressures, such as drought, to be exacerbated in the future [5]. Not only do droughts impact the direct supply of drinking water and water used among daily household activities, the effects of droughts can be felt across all systems. Droughts can put immense pressures on agricultural production, which affect the food supply; potentially decreasing the supply and raising costs [4]. Droughts can also impact economies due to their consequences among sectors such as tourism and recreation, energy, and transportation [6]. Environmental stressors, such as drought, must also be viewed as threat multipliers; their interaction with other factors may help to push regions into undesirable situations that may result in civil and international conflict as seen in regions such as Darfur and Syria [7].

The Impacts of Water Scarcity in Urban Settings

Urban centres deplete resources at higher rates than rural areas do, due to increased population density. In general, hydrological systems are affected with the addition of roads and buildings since the soil which is covered by asphalt is no longer able to absorb the water. As a result, natural water infiltration rates will decrease and rainfall runoff will increase[5]. This can substantially affect the health of the soil in urban centres, as well as reduce the rates of water absorption for further consumption by plants, animals and humans [5]. Additionally, the depletion of accessible water is further worsened via mismanaged water systems, pollution, privatization and overuse [5]. Irrigation for agricultural production is an enormous water user, and in the event of a water shortage, a common response is to reallocate the water for non-agricultural purposes [4]. As a consequence, water scarcity puts pressures on agriculture to reduce its water use, usually by installing drip-lines at high costs for the food producers [4]. Due to the high dependency of urban centres on rural food production this can lead to urban food insecurity caused by the decreased supply or raised prices of food [3].

In the face of water scarcity, political leaders are often pressured by companies and organizations to dictate where the limited water resources will be allocated, which may lead to civil unrest [5]. Everyday experiences of citizens are largely affected by the poor management of water: leading to the limitation of water usage in homes, as well as usage in health care sectors and issues pertaining to hygiene [8].

Grounding Water Scarcity

Preventative, sustainable water management practices are necessary to protect the economic, political, and social health of a city and its population. Cape Town is a rapidly urbanizing and growing city that has been painfully confronted by the increased effects of drought coupled with poor resource management. A fresh water crisis was, and still is, a constant threat to the urban dwellers of Cape Town. Social mobilization backed by political support has been key to Cape Town’s success in reducing water usage and ensuring responsible resource management.

Case Study of Theme/Issue

Day Zero in Cape Town

In 2018, Cape Town, a city of over 4.5 million people, experienced its most severe drought the city has ever seen: “Day Zero,” a day where the taps would run out, was a growing threat to citizens of Cape Town since the year of 2015 [9]. The root cause of the water crisis is still debated, with some arguing that mismanagement and lack of planning was the culprit while others argue that it was solely a climate caused event [10]. Regardless of the root cause, action had to be taken. As residential water usage made up 70% of the city’s water usage, pressure fell onto households. As the water crisis grew progressively intense, long lines formed at water taps and household restrictions were increased. The May 2017 guidelines of 100L/day per person were gradually reduced to a hard 50L/day per person by January 2018 [8]. Many measures were adopted by Cape Town to preserve the limited resources, such as the development of the Water Police, reduced water pressures, and the turning off of certain taps. However, the success of these restrictions would not be possible without public acceptance. Luckily, mass social mobilization, backed by political support occurred during this impending resource catastrophe which ultimately lead to the evasion of Day Zero.

Campaigns

A large amount of the city’s willingness to dramatically reduce their water consumption was the “extreme social engineering” by the Day Zero campaign that took place [8]. The campaign was launched to promote smart water usage and bring attention to the big water consumers such as heavy residential users, tourists and commercial users. The roots of the campaign started as “Think Water”, a softer campaign that began in 2016 with the slogan “Care a little, Save a lot” [9]. However, as the drought worsened, in the November of 2017 the city transitioned to the Day Zero campaign, which was created by Resolve Communications agency [9]. Citizens were called to respond to the crisis and reduce their water usage as part of their civic duty and neighbours were encouraged to inform fellow neighbours if they used too much water. As well, the government provided information and support for alternative water sources and such as reusing grey water and collecting sea water for household use. During this period, the mayor personally visited households that were recorded as consuming excessive amounts of water [8]. Through the use of websites, media campaigns and posters, the city was able to generate an effective marketing strategy that pushed Capetonians to become fixated on “water talk” and “water literacy” [9].

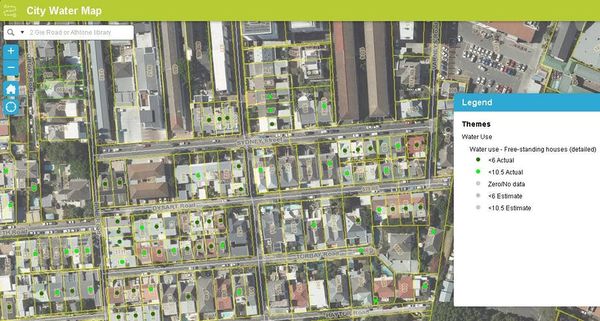

The Cape Town Water Map

A tangible example of an effective marketing strategy was the Cape Town Water Map which was launched in January of 2018. The goal of the map was to “publicly acknowledge households that saved water, thereby normalizing water conversation” [12]. Available online was a visual map of the city where households that met water saving targets were awarded green dots. The data represented on the map came from monthly water usage for free-standing houses in the city. This approach encouraged and rewarded the normalization of water saving behaviour that aimed to “paint the city green” rather than create a “name and shame” campaign [12]. Water reducing households increased dramatically over the first six months and the map was found to be a useful behavioural tactic [11].

Impact on Communities

Despite the positive mobilization, the water crisis heightened pre-existing inequalities within Cape Town and Greater South Africa. While the water restrictions and reductions were necessary, “the access, cost and benefits of water resource projects [were] often unequally distributed, leaving the poor to bear the greatest costs” [13]. In South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution, water was guaranteed as a human right [14]. However, the informal, low-income settlements in Cape Town did not receive the promised infrastructure, leaving them limited to the free but scarce public taps in the time of this crisis [14]. Arguments against private use of the city’s water stores, from companies such as Coca-Cola, generated widespread public response, especially from those who could not afford bottled water. Over seventy community-based groups from across the metropolitan Cape Town area unified together in the creation of the Cape Town Water Crisis Coalition to call for the reduction of private water usage [15]. Coca Cola Peninsula Beverages made efforts to reduce production water usage and to increase water availability via the creation of discount structures, preparing emergency water provisions and investing in the Greater Cape Town Water Fund [16]. Unification of city residents enabled the widespread mobilization of grassroots activists who supported water rights of all citizens.

Cape Town’s Successes

While government regulations and restrictions set the framework, the City relied on the mobilization of its citizens to drastically reduce water usage before Day Zero arrived. Rather than relying on physical restrictions, the city created campaigns and communicated with residents through “green nudges” that better influenced household behaviour than demanding restrictions [18]. Targeting the issue by providing ample information and creating an appeal to public good generated change among social norms, allowing for social pressures to assist in the reduction of water usage. The “green nudges”, as opposed to top-down restrictions, proved more successful in a place like South Africa where, due to preexisting socioeconomic and racial divisions, inequalities were heightened in a time of resource scarcity. While tariffs and physical restrictions are harder on poorer families, non-monetary incentives can be adopted by all [18]: “Promoting public awareness by transparently providing ample information to empower citizens has, indeed, been a cornerstone of the city’s drought response and a key aspect of its conservation strategy” [12]. The emphasis on behavioural focused change proved to be the most successful tactic used for the necessary change and the ultimate avoidance of Day Zero.

It is important to recognize that the strategies implemented by the City of Cape Town encouraged citizen engagement and problem solving. Instead of relying on fear tactics and physical restraints, the city was able to support grassroots style activism and meet their goal early. This style of public engagement can be applied to a wide range of social and environmental pressures. Over a three year period, Cape Town reduced daily water usage from 1.2 billion litres per day in 2015 to 511 million litres per day [9]. Even more astounding was that 400 million litres of the 689 million litre per day reduction occurred between February 2017 and February 201, this can be attributed to the successes of the Day Zero campaign [9]. The avoidance of Day Zero can be characterized by mass social mobilization that received strong governmental support.

Lessons Learned

The citizens of Cape Town demonstrated the ability to effectively organize and cooperate to reduce their water consumption. The high degree of social mobilization within the city ultimately pushed back the dreaded “Day Zero” and demonstrated that change can happen at the local level. The main reason for the public’s change in actions was due to the campaigns implemented by the City of Cape Town. In particular, the Day Zero Campaign focused on educating the public and initiating positive behavioural changes. These aspects caused the campaign to be highly successful in mobilizing the public. As a result, citizens changed how they consumed water.

One of the main takeaways from this case study was the serious consequences that coincide with a resource scarcity issue, particularly within urban contexts in the global south due to their high growth rates. The potential effects of this crisis would have been destructive to the political, social and economic sectors within the city, which highlights the importance of a sustainability approach when examining the development of urban centres. Another main takeaway is that a northern development theory solution is not the answer for all crises in the geographical south and east, instead there needs to be focus on grassroots level movements.

Moving forward, it would be worthwhile for similar campaigns or programs to be implemented in other urban areas of the geographical south and east. Issues surrounding resource scarcity and depletion are a current threat that many urban contexts face, especially as populations continue to grow. Cities that are wanting to reduce their citizen’s consumption of a resource should follow the aspects of the Day Zero Campaign to create strong social mobilization that is backed by government support. Even if a city does not currently face resource scarcity, it would be beneficial to educate citizens and encourage sustainable behaviour at the local level, due to the projected effects of climate change. However, social mobilization on its own is not the answer to these large issues: national and local governments, and large corporations must plan ahead and change the course of their actions by adopting sustainable practices before irreversible damage is done.

Overall, Cape Town’s ability to drastically reduce water usage provides hope that other serious issues surrounding resource scarcity can be alleviated with social mobilization. Public involvement and behavioural changes in response to resource scarcity must be prioritized as it betters the chances of internalization among a population. Public education regarding issues as pertinent as resource management in the face of scarcity better ensure that citizens will continuing to pursue increasingly sustainable lives, even after the climax of the crisis is over.

Reference List

- ↑ Seto, K. C., Fragkias, M., Güneralp, B., & Reilly, M. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of global urban land expansion. PloS one, 6(8), e23777.

- ↑ Szalińska, W., Otop, I., & Tokarczyk, T. (2018). Urban drought. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 45, p. 00095). EDP Sciences.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McPhee, S. (2019). Food security in cities of the global south. [PowerPoint Slides]. Retrieved from https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/20106/files/4373162?module_item_id=1094858

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Meinzen-Dick, R., Ringler, C. 2008. Water Reallocation: Drivers, Challenges, Threats and Solutions for the Poor. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14649880701811393?scroll=top&needAccess=true on Thursday, March 21st, 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Li, Y., Ye, Q., Liu, A., Meng, F., Zhang, W., Xiong, W., Wang, P., Wang, C. 2017. Seeking urbanization security and sustainability Multi-objective optimization of rainwater harvesting systems in China. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022169417302639 on Thursday, March 21st, 2019.

- ↑ Wilhite, D. A., Svoboda, M. D., & Hayes, M. J. (2007). Understanding the complex impacts of drought: A key to enhancing drought mitigation and preparedness. Water resources management, 21(5), 763-774.

- ↑ Sova, C. (2017). The First Climate Change Conflict. Retrieved from https://www.wfpusa.org/stories/the-first-climate-change-conflict/#

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Newkirk, V. (2018) Cape Town is an Omen. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/09/cape-south-south-africa-water-crisis/569317/ on March 3rd, 2019

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Robins, S. (2019). ‘Day Zero’, Hydraulic Citizenship and the Defence of the Commons in Cape Town: A Case Study of the Politics of Water and its Infrastructures (2017–2018), Journal of Southern African Studies, 45(2), 5-29.

- ↑ Wolkski, P. (2018). How severe is Cape Town's “Day Zero” drought?. Significance 15(2).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Water Map. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.capetown.gov.za/Family and home/Residential-utility-services/Residential-water-and-sanitation-services/cape-town-water-map

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Sinclair‐Smith, K., Mosdell, S., Kaiser, G., Lalla, Z., September, L., Mubadiro, C., ... & Visser, M. (2018). City of Cape Town's Water Map. Journal‐American Water Works Association, 110(9), 62-66.

- ↑ Mahlanza, L., Ziervogel, G., & Scott, D. (2016, December). Water, rights and poverty: an environmental justice approach to analysing water management devices in Cape Town. In Urban Forum (Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 363-382). Springer Netherlands.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Dawson, A. (2018, July 10). Cape Town has a new apartheid. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/07/10/cape-town/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.b87d8df85fa7

- ↑ Browdie, B. (2018). Cape Town's bottlers and brewers are coming under fire for guzzling water in a drought. Retrieved from: https://qz.com/africa/1214249/cape-tower-drought-crisis-coca-cola-bottlers-slammed-for-using-too-much-water/

- ↑ Edwards, C. (2018). Water crisis: Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverages to find ways to help with the provision of water to Cape Town. Retrieved from https://www.thesouthafrican.com/water-crisis-coca-cola-peninsula-beverages-to-find-ways-to-help/

- ↑ "The City of Cape Town". (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2019. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 18.0 18.1 Brick, K., De Martino, S., & Visser, M. (2017). Behavioural nudges for water conservation: Experimental evidence from Cape Town. Working paper. University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi. org/10.13140/RG. 2.2. 25430.75848.

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |