Course:GEOG352/2019/Post-Conflict Infrastructure Building in Aleppo

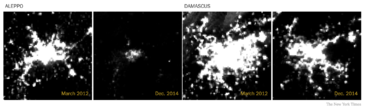

Post-conflict infrastructure building is important in the management of cities in the Global East and South, especially in war torn countries which operate as emerging economies before,during, and after their respective intrastate conflicts. These emerging economies that are being stalled by political conflicts causes economic disruptions, which further displace them from the current globalizing climate. Furthermore, post-conflict rebuilding contributes to the colonial influences on the integrity of the state. Syria is a country within the Middle East, surrounded by the economic powers of Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The Syrian regime and the Assad dictatorship has undoubtedly created a militant state and a functioning economy based on oil and small domestic trades. Two major cities within Syria, Aleppo and Damascus, have suffered intensive infrastructure loss in cultural remnants, social infrastructure, and economic staples that powered their daily functions.

Overview

Post-Conflict Rebuilding of Urban Infrastructure

Post-conflict rebuilding requires immense amounts of capital funding, especially when violent conflict causes a widespread of physical damage to a city's urban infrastructure. These damages are costly when considering the impacts of armed conflicts that heavy artillery, bombings, and urban warfare can have on the physical landscape of urban cities. There are many difficulties in rebuilding a city's public urban infrastructure, especially in the cases of post-conflict, where public and private institutions are not conveniently accessed and fully equipped right after an armed conflict. Furthermore, the damage warfare has on cities causes large amounts of debris and displacement of people and assets, therefore rebuilding is far beyond the issue of solely constructing buildings. One difficulty of post-conflict infrastructure building is the necessity of attracting private capital from foreign sources. This causes problems because with the introduction of foreign resources is the insertion of foreign political, cultural, and socio-economic influences that weaken the stability of rebuilding state. Discussed by Jordan Schwartz and Pablo Halkyard's paper on rebuilding infrastructure, they discuss the difficulties in a post-conflict country where they are either unable to absorb and implement foreign aid into a sustainable and growing platform or unable to attract foreign aid at all.[1] The suggest that for a rebuilding program to prosper, there are elements that governments and donor-led parties must follow, including: using large investment opportunities to stimulate investments and create a fluid economy, using insurance programs to mitigate risk, and recognizing the importance of small-scale businesses that contribute to the urban community's economy.[1]

Aliza Belman Inbal and Hanna Lerner discusses about "Constitutional Design, Identity, and Legitimacy in Post-Conflict Reconstruction" in Brinkerhoff's "Governance in Post-Conflict Societies"[2], the second difficulty to post-conflict rebuilding is the colonial aspect of foreign aid introduction to a conflicted based country. They explain that post-conflict societies often remain conflicted and divergent in socio-cultural aspects like "religion, ethnicity, nationality, and ideologies".[2] In post-conflict areas, national identity and personal identity are often dispersed and astray from what the state was once built upon, especially when the conflict is between civil participants and intrastate. Furthermore, this creates a difficulty in starting reparations when foreign forces are attempting to offer aid while the domestic community is in chaos, both the formal institutions and informal communities struggle to grasp their place in the new post-conflict society.

Rebuilding as a Local & Global Phenomenon

The Syrian civil war is contained as a local phenomenon because of its cause, as dictatorship is slowly weaning and democracy is the dominant government structure. It is also a global phenomenon because intrastate wars and conflict inflict much greater social costs and long-term harm to the welfare of the state, well beyond militant and civilian casualties. Civil conflicts cause immense amounts of damage to the necessary social infrastructures such as food supplies and hospitals, as well as energy power plants that power the city. The global phenomenon here is that multiple civil conflicts that occur simultaneously across the globe create multiple displacements of citizens, which damage the social and cultural integrity of these states. Post-conflict rebuilding is global phenomenon that exists as a temporal issue, as interstate and intrastate wars have existed worldwide throughout history, rebuilding has been a remediation process for the victims of violent conflict. Rebuilding is physically a repeatable process for tangible infrastructures, buildings, and public assets, but is a short-term method into reducing conflicts as a whole. More importantly, rebuilding causes fractures and displacements in culture, people, and history, and repeated processes will further weaken urban infrastructure and formal economies.

Displacements are not contained within Syria, but across all middle eastern states that are involved with the conflict, including Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Turkey. Civil conflicts cause immense amounts of damage to the necessary social infrastructures such as food supplies and hospitals, as well as energy power plants that power the city. The global phenomenon here is that multiple civil conflicts that occur simultaneously across the globe create multiple displacements of citizens, which damage the social and cultural integrity of these states. Moreover, the civil conflict within Syria has introduced a plethora of social entities into the local society of Aleppo, including the Americans, Kurds, Iraqi, ISIS, and various NGO’s that have populated and diluted the population of Syria of Syrian people.

Case Study

Architectural History of Aleppo

Ancient Aleppo is a city preserved in a rich history of religious, cultural, and linguistic heterogeneity. Considered as one of the world's most antique cities to be continuously inhabited, the city not only served as the crossroad of a vast network of major trade routes dating back from the second Millenium,[3] but also a testimony to the legacies left by many powerful empires in the form of monuments and architectural remains that has sustained throughout time. Over the course of Aleppo's urban development as a prime setting for global interaction and commerce, great infrastructures created and built during this period became increasingly important to the economic and social welfare of the city.[4] The Citadel of Aleppo, for instance, is one of the most significant historical sites that was built, damaged, and restored as a defence fortification over many different points in time. As an Islamic landmark with traces of Greek, Byzantine, and Roman ruins, the Citadel is a metaphorical storage space of cultural diversity that reflects the various influences and aspects of the Empires that crossed paths with Aleppo. Evidence of the early Graeco-Roman street layout and remnants of the 6th century Christian buildings is demonstrated around the walled city that surrounds the Citadel[5], while medieval walls, gates, and related structures highlight the Ayyubid and Mameluk dynasty's development of the city.[5] As one of the many post-colonial cities in Syria, the historical ruins and structures of Aleppo reflect a phenomenal period of time in history characterized by thriving commercial and economic activity.

Public Service Infrastructures Before Conflict

With a pre-war population of 2-3 million, the Syrian government ran a comprehensive public service infrastructure to serve the needs of a major population center. For example, the Al-Khafsah water plant was the main source of water for the city until was bombed by government forces in 2015.[6] Both citizens and opposition forces alike suffered through drought conditions for three months without access to clean water. The cities water system was under government control before the conflict began. However, it has constantly changed hands from group to group such as ISIS, and al-Nusra. What UNICEF found was that the surface level pipelines were often sabotaged by all armed groups, causing massage spillages of water and worsening drought conditions

In terms of healthcare, exiting hospitals have been commandeered by whichever occupying force controls the region. According to the World Bank, approximately 60% of healthcare facilities in Aleppo have been damaged or destroyed since the start of the conflict, to February 2017.[7] To compensate for the loss of existing public infrastructure, independent NGO’s along with the UN have built hospitals underground and spread the different practices across the city to prevent a fatal blow to the remaining healthcare system by air campaigns and barrel bombs.

During Conflict

Prior to the war, the city’s population totaled to 2 million, and was considered a major commercial city for Syria.[8] During the war, Aleppo became a major symbolic and strategic stronghold for rebel forces on the front against Daesh and Assad. Much of the city’s previous infrastructure was decimated during the regime’s attempts to retake the city. According to Böttcher, the Assad regime in 2013 began using helicopter delivered barrel bombs that damaged vital infrastructure and caused further collateral damage.[9] After reclaiming Aleppo, the government allowed internally displaced residence to return home. The Syrian government has also begun to build power lines extending from Damascus to Aleppo for more consistently running power.[8]

Much of Aleppo’s Old City has been destroyed by the prolonged conflict. UNESCO designated the Old City as a Heritage Site (a place of both historical and cultural significance). While some parts can be restored to the former glory, traditional houses and unique districts and alleyways are beyond repair.[10] President al-Assad has expressed an urgent desire to rebuild the old city for political, symbolic, and economic reasons. UNESCO has claimed that local effort and craftsman will be necessary to rebuild. Namely, to consult on the division of land between shops, homes and the public areas. However, many local craftsmen have either died, remain internally displaced, or sided with rebels and are fleeing the regime.

In the Fall of Aleppo in 2016, 100,000 residents were sieged suffering the use of barrel bombs, bombardment, and ground attacks. After the fall of Aleppo, the Syrian government and rebels came to an agreement to internally displace approximately 111,000 opposition members to other territories.[9] The use of sieging and bombardment caused serious humanitarian concerns, with residents becoming political pawns of the opposing sides.The siege of Aleppo created numerous humanitarian crisis’s such as lacking access to clean water and electricity, poor medical treatment, and starvation. An estimated 31,000 died as a result of this.[9]

Effects and Consequences

The implications of War in Syria can be described as the destruction of infrastructure and displacement of citizens. While the periphery of the country is left isolated without access to basic resources. Aleppo, a high-density city with strong trade ties and interaction between combatants and civilians attracts Syrians in refuge.[11] Aleppo has the ability to engage in foreign trade and can provide provisional imports for the civilians. Conflict and violence places pressure on the economy, affecting productivity, wages, trade, access to healthcare, and private consumption. As a result, there has been a severe contraction of the formal economy.[12] In its place has emerged a growing informal sector within Aleppo that can be described as a war economy. With the destruction of infrastructure and domestic production civilians may engage with these war economies creating a supply chain of imported goods from external production.[12] This informality facilitates “collective efficacy translated into actions of mobilization of residents to achieve collective demands".[13] Becoming entrenched in such war economies has implications for the post war reconstruction of Aleppo. Moreover, fragmentation of the Aleppo can be seen as the product of network formation. Such networks can offer insight to the role war economies play in propelling violence. The formation of these social networks are often determined by a number of factors such as resource access, supply demand, and access to markets or weapons.[12] Supply chains of medicine, food and protection foster dependence within these social networks through economic ties. Resulting entrenchment of war economies coupled with group conflicts surrounding the resource demands. In regard to post-war reconstruction, planners should find ways of reducing these network dependencies while finding ways to integrate these social networks and economic agencies to generate domestic growth.

Lessons Learned

Aleppo demonstrates the necessity for strong urban infrastructure within a functioning city. War, in addition to its destructive power, is expensive. The devastation of civil war is a difficult task for a single state to piece back together. It takes careful planning and immense funding to achieve the rehabilitation of an urban centre. As such, food, water, and energy prices are extremely high. In contrast, a majority of Aleppo's remaining population is either unemployed or informally employed making any standard of living hard to maintain. Syrians, including children, have had to find jobs in the informal sector to offset the loss of income. Many of which are living in extreme poverty, unable to meet basic food and medical needs.

During the reconstruction process, the immediate economic challenge may be the employment collapse and social fragmentation. In order to overcome these challenges, further diversification of the economy through private sector development is critical. Such will increase productivity for the long term by raising the skills of its labor force, rather than just focusing on the control and exploitation of resources such as oil or foreign investments from geopolitical powers. Therefore, considerable efforts need to go toward rebuilding the lives of internally displaced people, and to encouraging the return and reintegration of refugees in order to construct a productive and sustainable economy. If this is not addressed, post war Syria will remain poor and divided. Forcing its population to rely on UN aid rather than building Aleppo from the ground up.

The context of the conflict in Aleppo offers insight to the strength of an informal sector. It illustrates the sense of community that is formed when citizens are exposed to health and security risks. Furthermore, other urban centers should work with, not against, informality when constructing economic and social productivity.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Schwartz, J., & Halkyard, P. (2006). Rebuilding infrastructure World Bank, Washington, DC.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2007). Governance in post-conflict societies: Rebuilding fragile states. New York;London [England];: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203965122

- ↑ Buffenstein, Alyssa (May 30, 2017). "A Monumental Loss: Here Are the Most Significant Cultural Heritage Sites That ISIS Has Destroyed to Date". Art News. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ↑ Rabo, Annika (2012). "Conviviality and Conflict in Contemporary Aleppo". Religious Minorities in the Middle East – via The Netherlands Brill.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/21

- ↑ Chan , A., Danforth , J., & del Valle , N. (2016). Water as a Weapon of War: The Syrian Conflict. Center for Spatial Research, Columbia University. Retrieved from http://c4sr.columbia.edu/conflict-urbanism-aleppo/seminar/Case-Studies/Water-as-a-War-Weapon/Water-as-a-War-Weapon.html

- ↑ World Bank . (2017). Syria Damage Assessment. Washington DC : World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530541512657033401/pdf/121943-WP-P161647-PUBLIC-Syria-Damage-Assessment.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 McKenzie, Sheena (March 15, 2018). "How seven years of war turned Syria's cities into 'hell on Earth'". CNN. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Böttcher, A. (2017). Humanitarian Aid and the Battle of Aleppo. Syddansk Universitet , Centre for Contemporary Middle East Studies.

- ↑ McDowall, Angus (August 3, 2017). "Aleppo's Old City can be rebuilt, UNESCO official says". Reuters. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ↑ Brown, Kaysie (September 2006). "War Economies and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding: Identifying a Weak Link". Journal of Peacebuilding and Development. 3(1): 6–19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Abboud, Samer (March 19, 2017). "Social Change, Network Formation and Syria's War Economies". Middle East Policy. 24(1): 92–107 – via Wiley.

- ↑ Ahmad, Balsam (October 28, 2014). "Exploring the Role of Triangulation in the Production of Knowledge for Urban Health Policy: An Empirical Study from Informal Settlements in Aleppo, Syria". Forum for Development Studies. 41(3): 433–454.

- ↑ Pecanha, Sergio (March 12, 2015). "Syria After Four Years of Mayhem". NY Times. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |