Course:GEOG352/2019/Gentrification in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Gentrification has affected cities around the world, and its impacts include loss of community, discrimination, displacement, and inability to access secure job markets. Although gentrification is a global phenomenon, it is typically framed and studied from the Global North perspective. To have a well-rounded understanding of gentrification, it is important to study local contexts and gentrification processes in the Global South. An interesting case is Buenos Aires, which has shown increased rural-to-urban and international migration due to growing job opportunities and improved living standards. However, the city is also experiencing high rates of gentrification, demonstrating the flaws of the Global North perspective where linear economic growth benefits everyone. In Buenos Aires, gentrification has transpired due to neoliberal city policies and private infrastructure investments pushing the urban poor into precarious housing situations. Despite the fact that Buenos Aires has shown overall economic growth within the last several years, it is essential to use a localized urban geographic lens to study the social inequality that arises from mass migration and the increased strain on limited resources and space.

Overview

Scholars have described gentrification as the demographic shift in an area from a lower to a higher socio-economic class due to infrastructure and service enhancements. The concept of gentrification originated from Ruth Glass in 1964. Her idea of gentrification focused on “residential rehabilitation”, however recent findings note that it involves more of a visual shift in a neighbourhood towards more consumption and services[1]. Gentrification is often framed by state or corporate agents as “urban renewal” or “redevelopment”[2] which overlooks its negative social impacts. Urban renewal and redevelopment can foster investment in areas where there is low economic activity and introduce more businesses, job opportunities, and increased safety[3]. However, these benefits are often not enjoyed by the original lower-income residents that are pushed out of the neighbourhood as a result. These urban renewal projects also result in indirect and unofficial forms of evictions in informal neighbourhoods, which make it difficult for the displaced to resist their displacement[4].

Gentrification originally emerged from Western Europe, which makes applying the original theory to Latin American cities inadequate. This theory cannot account for each city’s unique composition, such as climate, cultural traditions, histories, social networks, and political systems. Moreover, several scholars have argued that gentrification is a dynamic, evolving concept and can therefore be adapted to new contexts[5]. Western contexts can learn from case studies within the Global South, and vice versa, allowing for new gentrification theories to emerge that are more adaptive to contemporary and changing processes.

Although the Argentine population is still recovering from the 2001 economic crisis, Pew Research[6] has found that Argentina’s middle class is the fastest-growing class in Latin America. However, this bracket includes the lower and higher ends of the middle class, the latter often facilitating gentrification and the former being displaced. This growing middle class is distinct from places in the Global North such as the United States where income inequality is increasing according to the Gini coefficient. In contrast, Argentina has shown a decline in its Gini coefficient from 53.8 in 2002 to 40.6 in 2017[7]. The country had the second largest economy in South America with a GDP of $828.20 billion (USD) in 2018[8]. Buenos Aires accounted for about 20% of Argentina’s total GDP in 2018 achieving 10% economic growth within the last 5 years[9]. However, the Gini coefficient and GDP measures offer a limited scope on how gentrification manifests throughout Buenos Aires. These economic indicators imply that inequality is decreasing and that wealth is increasing in Argentina. It is important to examine the dispersion of wealth and whether the higher socio-economic classes and larger private enterprises benefit the most. Taking a closer look at Buenos Aires allows for a deconstruction of original Global North theories as well as a more nuanced study of gentrification by analyzing the commodification of tango, discriminatory policies, and planning models specific to Buenos Aires.

Historical Context

From 1880 to 1914, over 4 million immigrants arrived from Europe[10]. By 1942, the percentage of the urban population in Argentina rose by 62% which accelerated urbanization, particularly in Buenos Aires, resulting in aggravated housing problems. In 1943, a military coup led to Juan Peron's election. Peron began an interventionist state and launched a public housing program, dubbed “Peronism”[11]. During the 50s and 60s the Peronist Strategy shifted to the Developmentalist Strategy and an ill-planned, over-ambitious plan to eliminate “shanty towns” was enacted. The process also disrupted community ties and created inadequate living environments[12]. The 1960’s, 70s and 80s marked a period of political turmoil and steady economic decline[13]. In 1973, thousands of slum-dwellers took possession of empty housing within the city[14]. In 1976, a political party called Process of National Reorganization took power and led to a dictatorship lasting until 1983. During this time, the government enacted regressive economic policies that led to a neoliberal economy[15]. By the early 1990s, industrial activities began disappearing and this created an economic crisis for the working-class[16]. During this time, urbanization “supported by public-private projects, changes in planning and building codes, and investment infrastructure” accelerated[17]. In the 1990s and early 2000s a process of urban renewal began in the city’s southern neighbourhoods[18]. The economic crisis and neoliberal partnerships contributed to the protection of corporate profits, wealth disparities, and displacement of lower-income groups via gentrification.

Present Day

As of 2016, more than 2 million inhabitants are living in inadequate housing without access to basic infrastructure in Buenos Aires[19]. The new push for urban redevelopment has disproportionately affected the low- and middle-income communities that have been displaced by higher rents and forced evictions[20]. The development of new commercial spaces, services, and housing aimed at high-income residents has been driven by private firms purchasing unused land and the growth of middle-income and luxury rental markets[21]. Although the city has formally recognized the municipal “housing crisis”, little has been done to resolve the housing deficit[22].

Over the last two decades, many working-class neighbourhoods have transformed into trendy and artistic neighbourhoods that appeal to middle- to upper-class buyers and young urban professionals. The city’s European architecture attracts tourists every year who come to experience the “Paris of the South”[23]. Many residents of these touristic neighbourhoods have faced forced evictions. This is due to the “revitalization” of cultural heritage sites and the subsequent transformation of predominantly working-class residential centres[24]. As a result, social tensions may arise from loss of social diversity and further contribute to a weakened sense of community, stigmatization from higher socioeconomic neighbours and/or wealthy tourists, and the destruction of architectural heritage[25][26][27].

Neighbourhood Examples

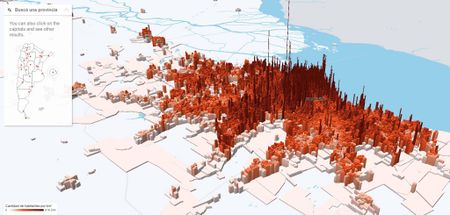

Economic opportunities have attracted many to Buenos Aires with recent city data recording over 3 million city dwellers[28]. In 2016, Buenos Aires had a density of 15,000 inhabitants per km2 [28]. To put this into perspective, the city of Vancouver had a density of 5,492.6 inhabitants per km2 in 2016[29]. Mass rural-to-urban and international migration has sped up gentrification as housing developers try to meet increased housing demands. Two interesting cases of gentrification include the neighborhoods of El Abasto and Palermo Viejo.

El Abasto:

El Abasto is in the north-center of Buenos Aires, known for its historic ties with famous tango dancer Carlos Gardel, tango-themed souvenir shops, and the famous Shopping Abasto. Before the 1970’s mass Peruvian migration, the neighborhood was mostly composed of working-class European descendants[27]. The neighborhood was centered around economic activities in the Abasto public market centre until its closure in 1984[30]. In 1998, the large Argentinian real estate and investment company Inversiones y Representaciones SA (IRSA, in English Investment and Brokerage Inc.) invested $200,000,000 USD to restructure the public market centre into Shopping Abasto[31]. This followed with further investments like the construction of 3 luxury tower apartments (known as torres-country), the Holiday Inn Hotel, and a street and statue dedicated to Carlos Gardel all surrounding the newly-built Shopping Abasto[32]. The increase in specialty stores, souvenir shops, and restaurants attracted many migrants and informal workers to El Abasto for job opportunities and steadier incomes. However, this massive investment in built environments resulted in increased real estate prices, pushing lower income families into precarious housing settlements and further away from El Abasto job opportunities[33].

In 2016, a fire destroyed an informal housing complex in Calle Zelaya and left over 30 families homeless[34]. These low-income families stood in solidarity with other displaced families and gained assistance from social organizations (such as Coordinadora de Inquilonos de Buenos Aires (CIBA)) and political parties to have their voices heard[35]. Through occupying a public space outside the burnt complex, Peruvian immigrants created a strong, united front to demonstrate their rights to basic, safe housing in front of neighbors, tourists, and city officials[36]. Interviews with displaced families demonstrated two common socio-economic problems after displacement in El Abasto:

1) distrust from real estate agents and landlords regarding ability to pay rent[37].

2) xenophobic stigmatization from higher socio-economic status neighbors and well-off tourists[37].

El Abasto has become a tourist-centric and middle-upper class space. The widespread, discriminatory rhetoric from developers and other elite actors depicts immigrants as “space grabbers” and “criminals” who tarnish the aesthetic and cultural aspects of El Abasto’s tango-themed streets[37]. Displacement of informal squatters, through indirect evictions (fires and financial compensation) or direct evictions (police raids), is seen as a gentrification tool to protect El Abasto’s cultural identity and create available space for continual investment in beautifying the quarter[38]. Utilizing a cultural dance such as tango to justify gentrification is unique to the local context and differentiates Buenos Aires from other Global North cities.

Palermo Viejo:

Palermo Viejo is one of Buenos Aires’ most cosmopolitan neighborhoods, located in Northern Buenos Aires with fancy shops, restaurants, and houses attracting local and foreign tourists. In the 1970’s, older homes were remodeled for commercial purposes and luxury houses[39]. Even with the 2001-2002 national ‘peso’ crisis, foreigners and elite Argentinians spared from the crisis continued to invest in the built environment of Palermo Viejo to gain profits[40]. The dated Código de Planamiento Urbana (CPU) (Urban Planning Code) from 1977 also affected rental prices through its loose regulations and protections over historical property, allowing developers to build on abandoned plots[40]. The arrival of Nike and other big multinational corporations after 2002 portrayed Palermo Viejo as an island of prosperity and upper-middle class access to the Global North’s goods and services[40]. Essentially the neighborhood was centered around high-end consumption in gastronomic experiences, architectural design, and artisanal clothing.

Throughout the past decade, activist groups began to fight harder against gentrification through pressuring City Hall to increase protections of cultural heritage sites and public land[26]. In 2012, the activist group Basta de Demoler (Stop the Demolitions) sued City Hall for construction plans at the historic site Plaza Francia subway station[26]. The activists succeeded in protecting this historic site by moving the project to another location and pushing back against political pressure to build. However, even with the CPU’s revision in 2018, Palermo Viejo and the Palermo quarter continue to serve as a high-end entertainment and consumer hotspot for wealthier individuals where lower income families go to work due to increased job opportunities[41].

City and Advocacy Group Responses:

Many solutions have been proposed to tackle gentrification in Buenos Aires by public and non-profit groups. For example, Plan Microcentro, a city planning initiative started in 2012, sought to update the city’s neglected historic business district. It promoted tourism, creating space for hotels and the “revalorization” of property[42]." However, the plan had negative implications for the working-class district residents, including rising land prices and tax incentives that benefited the rich[43]. Beautifying the city was promoted as a way of creating a more sustainable city, but in reality, its market-oriented objectives and desire to increase property values revealed the gentrifying nature of the project. Other policy changes, such as Law 341, have been implemented to combat gentrification and provide housing. These policy changes mainly resulted from grassroots initiatives from the 1980s. The law provides soft loans to facilitate low-income households’ access to housing, with 10,101 families registering for this new program between 2001 and 2012[44]. However, this policy promotes private property systems by lacking limitations to sell or rent properties once they are built, continuing the capitalist cycle[45].

Additionally, non-profit advocacy groups such as Habitar have lobbied the city government to improve fair access to housing. Activists have advocated for the state to take ownership of land occupied by slums and lease it to the residents to prevent market-driven gentrification and allow neighborhood improvement[46]. Other advocacy groups such as CIBA work towards radical change via protest and collective organization to aid residents facing eviction[47]. CIBA mainly works with families who have been forced to move into informal hotels[48]. They often fight to improve existing programs, such as Atencíon a Familias en Situacíon de Calle (AFSC), a government subsidy program, and advocate for greater equity for residents.

Another strategy that many NGOs, international donor agencies, and entrepreneurs pursue is promoting small enterprises to reduce overall poverty and decrease the need for the informal settlements.[49] Other actions for addressing gentrification have been proposed by The International Alliance of Inhabitants (a network of organizations fighting for housing and city rights)[50], which include:

- Lobbying the state[51].

- Territory-related actions such as providing advice on abusive rents, evictions, home improvements, land ownership regulation, etc[51].

- Improving issue visibility through artistic public space interventions, attending seminars and forums, and promoting the housing problem in media[51][4].

Lessons Learned

There are certain applicable aspects of the Global North gentrification theory such as immigration, urbanization, neoliberalism, and planning policy which occur in both Global North and South contexts. However, the Global North’s economic indicators do not provide an in-depth understanding of a city’s social, cultural, and political makeup. When analyzing urban contexts, this case has shown that researchers cannot solely look at economic progress and assume that it will solve issues like gentrification and social inequality. Additionally, gentrification transpires uniquely in different cities and highlights the importance of local context as seen in the example of the cultural commodification of tango in Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires has attracted investment with its relaxed neoliberal policies and initiatives, such as Plan Microcentro. However, these initiatives do not equally benefit or involve the majority of the urban population, and mostly serve middle-upper class groups and multinational corporations. This research has revealed the importance of having a multi-stakeholder approach to urbanization and gentrification to create a platform for the urban poor to voice their needs for proper housing and formulate a more equal city planning model.

Further steps to enhance this body of research include building academic partnerships and collaborations between Global North and South research communities to pool funding, allow for balanced perspectives, and overcome language barriers. This would also allow for closer examination of local contexts. Major research gaps include a lack of data on corporate real estate lobbying, evaluations on the effectiveness of public policies like Law 341, and further case studies of other neighborhoods such as Puerto Madero, Saavedra, Villa Urquiza, and/or San Telmo. Working to close these research gaps would enable a deeper understanding of the intricacies and different influences in the Buenos Aires housing market as well as offer more concrete solutions to gentrification.

Reference List

- ↑ Tom Slater. "Gentrification of the City." The New Blackwell Companion to the City (2011), 573.

- ↑ John J. Betancur. "Gentrification in latin america: Overview and critical analysis." Urban Studies Research (2014), 4.

- ↑ “Managing the Potential Undesirable Impacts of Urban Regeneration: Gentrification and Loss of Social Capital.” The World Bank, accessed April 3, 2019, https://urban-regeneration.worldbank.org/node/45.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Vandana Desai and Alex Loftus. "Speculating on slums: Infrastructural fixes in informal housing in the global south." Antipode 45, no. 4 (2013), 792.

- ↑ Elvin Wyly. "The evolving state of gentrification." Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 110, no. 1 (2019), 13.

- ↑ George Gao. “Latin America’s middle class grows, but in some regions more than others.” Pew Research Center (2015), accessed April 3, 2019, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/07/20/latin-americas-middle-class-grows-but-in-some-regions-more-than-others/.

- ↑ “Gini Index (World Bank Estimate).” The World Bank, accessed April 3, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=AR.

- ↑ “Canada - Argentina Relations,” Government of Canada, last modified March 2018, accessed April 3, 2019, https://www.canadainternational.gc.ca/ci-ci/assets/pdfs/fact_sheet-fiche_documentaire/Argentina-FS-en.pdf

- ↑ “BA in figures,” Buenos Aires Ciudad, accessed April 3, 2019, https://turismo.buenosaires.gob.ar/en/article/ba-figures

- ↑ Rosa Aboy. “The right to a home: public housing in post-World War II Buenos Aires.” Journal of Urban History (2007), 493.

- ↑ Aboy, “The right to a home,” 494.

- ↑ Lindsey Dubois. The politics of the past in an Argentine working-class neighbourhood. (University of Toronto Press, 2005). 52.

- ↑ Dubois, The politics of the past in an Argentine working-class neighbourhood, 8.

- ↑ Dubois, The politics of the past in an Argentine working-class neighbourhood, 47.

- ↑ Dubois, The politics of the past in an Argentine working-class neighbourhood, 3.

- ↑ Dubois, The politics of the past in an Argentine working-class neighbourhood, 5.

- ↑ Maria C. Rodriguez and Maria M. Di Virgilio. “Seeing from the South: Refocusing Urban Planning on the Globe’s Central Urban Issues." Urban Geography (2016), 1222.

- ↑ Rodriguez and Di Virgilio, “Seeing from the South,” 1222.

- ↑ Axel Borsdorf, Rodrigo Hidalgo, and Sonia Vidal-Koppmann. “Social segregation and gated communities in Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires. A comparison.” Habitat International (2016), 22.

- ↑ Solange Muñoz. “A look inside the struggle for housing in Buenos Aires, Argentina.” Urban Geography (2017), 1252.

- ↑ Rodriguez and Di Virgilio, “A city for all?,” 1223.

- ↑ Muñoz, “A look inside the struggle for housing,” 1253.

- ↑ Dubois, The politics of the past in an Argentine working-class neighbourhood, 5.

- ↑ Rodriguez and Di Virgilio, “A city for all?,” 1217.

- ↑ Loretta Lees, Hyun Bang Shin, and Ernesto López Morales. Global Gentrifications: Uneven Development and Displacement. Page 204. Bristol, UK: Policy Press, 2015. Accessed April 3, 2019. https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=rd16BgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA199&dq=gentrification buenos aires&ots=wTOSO0aTpO&sig=Q8oUuzB9HdAmN2qSB9vws54zaIQ#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Jayson McNamara, “Development in City prompts debate over gentrification, cultural heritage,” Buenos Aires Times, last modified April 28, 2018, accessed April 3, 2019, http://batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/development-in-city-prompts-debate-over-gentrification-cultural-heritage.phtml.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Francisco José Cuberos Gallardo, “Relaciones interétnicas y lucha contra la gentrificación en el barrio de El Abasto (Buenos Aires),” Scripta Nova Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales Universitat de Barcelona 22, no. 596 (2018): 9, accessed April 3, 2019, http://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/ScriptaNova/article/view/20093/23986.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 “Buenos Aires en Números,” Buenos Aires Ciudad 5, no. 5 (2018): 10, accessed April 3, 2019, https://www.estadisticaciudad.gob.ar/eyc/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2017_05_buenosaires_en_numeros.pdf

- ↑ "Census Profile, 2016 Census," Statistics Canada, last modified February 28, 2019, accessed April 3, 2019, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&TABID=1&B1=All&Code1=5915022&SearchText=vancouver

- ↑ Gallardo, “Relaciones interétnicas y lucha contra la gentrificación en el barrio de El Abasto (Buenos Aires),” 9.

- ↑ Gallardo, “Relaciones interétnicas y lucha contra la gentrificación en el barrio de El Abasto (Buenos Aires),” 10.

- ↑ Ibán Díaz-Parraet and Francisco José Cuberos Gallardo, “Políticas de higienización y gentrificación. Aportaciones desde el urbanismo latinoamericano,” OBETS. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 13, no. 1 (2018): 308, accessed April 3, 2019, doi: 10.14198/OBETS2018.13.1.11.

- ↑ Muñoz, “A look inside the struggle for housing in Buenos Aires, Argentina,” 1253.

- ↑ Gallardo, 3.

- ↑ Gallardo, 3.

- ↑ Parra et al. “Políticas de higienización y gentrificación. Aportaciones desde el urbanismo latinoamericano,” 312.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Gallardo, 15.

- ↑ Michael Janoschka and Jorge Sequera, “Gentrification in Latin America: addressing the politics and geographies of displacement,” Urban Geography 37, no. 8 (2016): 1183, accessed April 3, 2019, doi: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1103995.

- ↑ Serge Schwartzmann, “Transformations urbaines à Palermo Viejo, Buenos Aires : jeu d'acteurs sur fond de gentrification,” Espace et sociétés 3, no. 138 (2009): 135-152, accessed April 3, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3917/esp.138.0135

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Schwartzmann, “Transformations urbaines à Palermo Viejo, Buenos Aires : jeu d'acteurs sur fond de gentrification.”

- ↑ “La Ciudad tiene un nuevo Código Urbanístico,” Buenos Aires Ciudad, last modified January 10, 2019, accessed April 3, 2019, https://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/planeamiento/noticias/la-ciudad-tiene-un-nuevo-codigo-urbanistico.

- ↑ Jacob Lederman. “Urban fads and consensual fictions.” City and Community (2015), 56.

- ↑ Lederman, “Urban fads and consensual fictions,” 56.

- ↑ Rodriguez and Di Virgilio, “A city for all?,” 1216.

- ↑ Marielly Casanova, Social Strategies Building the City: A Re-conceptualization of Social Housing in Latin America (Münster: LIT Verlag Münster, 2019), 237.

- ↑ Ciara Nugent. "Hidden City: Will Giving Residents Land Rights Transform a Buenos Aires Slum?" The Guardian, June 19, 2018. Accessed April 3, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/jun/19/hidden-city-will-giving-residents-land-rights-transform-a-buenos-aires-slum-.

- ↑ Muñoz, “A look inside the struggle for housing,” 1254.

- ↑ Muñoz, “A look inside the struggle for housing,” 1256.

- ↑ AlSayyad, Nezar. Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia. Lexington Books, 2004.

- ↑ "Who We Are." International Alliance of Inhabitants. Accessed April 3, 2019. https://www.habitants.org/who_we_are.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 "Case From Argentina, Buenos Aires: Evictions and Gentrification in the Historic and Tourist Neighbourhood La Boca." International Alliance of Inhabitants. September 20, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2019. https://www.habitants.org/international_tribunal_on_evictions/evictions_cases/6th_session_2017/case_from_argentina_buenos_aires_evictions_and_gentrification_in_the_historic_and_tourist_neighbourhood_la_boca.

| This urbanization resource was created by Will Engle. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |