Course:FRST370/The Sutlej Yamuna Link Canal between Punjab and Haryana States, India: assessing its contribution to the desertification of the Punjab

Summary

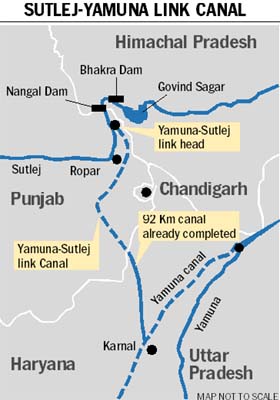

The Sutlej Yamuna Link Canal or SYL Canal is an unfinished water linkage between the two states of Punjab and Haryana in Northern India. The initial purpose of the canal was to redistribute water from three of Punjab’s rivers, the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej to the state of Haryana[1]. Currently, the canal sits unfinished due to disagreements between the two states on the issue of water sharing[2]. The rising concern of Punjab's groundwater levels depleting are one of the main drivers for Punjab's oppositions against the canal. These concerns are backed by data analysis of the land performed by NASA [2][3][4]. This case study will be discussing the various factors that have the potential of emerging from this situation as well as what has already been observed over the course of this 56-year dispute. Following these topics, some alternative routes are also introduced.

Keywords

- SYL: Sutlej Yamuna Link

- MAF: Million Acre-Feet/Year

- Riparian Law: Universally accepted model that a river is a part and parcel of the territory of Riparian States which have exclusive control over it[5].

Introduction

This case study is located in India. Primarily focusing on the water conflict that has arisen between the states of Punjab and Haryana.

Before the partition of British India, the province of Punjab held a great swat of land which extended from the Indus river in the West to the Yamuna river in the East. The land had water flowing from the Indus river and its tributaries Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej as well as the Yamuna River[5]. During this period the riparian doctrine for river water was used[6].

In 1947, the partition of British India took place which resulted in the formation of two new countries: India and Pakistan. This also resulted in the division of a unified Punjab into East and West Punjab. The Eastern part of Punjab was handed to India while the Western part was handed to Pakistan. Both countries have stuck with the name Punjab and therefore both countries have a province/state called Punjab[5].

The Indus river basin was split between India and Pakistan after the partition under the Indus Water Treaty. Under the treaty which was brokered by the World Bank, India received three rivers: Sutlej, Beas, and Ravi. Pakistan received three rivers as well, which are Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab[2]. Initially, this treaty was supposed to be signed under a riparian model which was ultimately not used in the end. Instead, a model of cooperation and friendship was used to show goodwill between the countries[6].

In 1966 East Punjab experienced another split. The people of present-day Haryana (Indian State) sought independence from Punjab (India)[2]. The creation of Haryana from Punjab presented the problem of giving Haryana its share of river waters. For Haryana to get its share of the waters of the Sutlej and its tributary Beas, a canal linking the Sutlej with the Yamuna was proposed by Haryana[6]. Also, Haryana demanded at least 4.8 MAF after separation from Punjab[7]. However, Punjab only wants to only allocate the MAF determined for Haryana during pre-partition which was approximately 1.9 MAF and is looking to apply the riparian principle when it comes to water allocation[6].

This water conflict between the two states has continued since the formation of Haryana to the present day. Since both states are agricultural in nature, neither state wants to be left with unfavourable treatment when it comes to water sharing. This is due to the fact that water availability in this region is already scarce and will only decrease in the future. This means that the livelihood of groups such as the farmers in both states depends on water and therefore this water dispute is quite important for both states.

Description of SYL Dispute

| Date | Summary | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | The Indus River treaty is signed | A major water dispute between post-partition India and Pakistan is settled via the World Bank in September of 1960. The Indus water treaty gives India unrestricted use of the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers. Pakistan retains control over the Jehlum, and Chenab rivers of West Punjab (Pakistan) [5]. |

| 1966 | Haryana splits from Punjab | The state of Haryana is formed from a split with Eastern Punjab. Haryana demands a canal linkage (SYL canal) to receive water from Punjab’s rivers. The state also demands a share of 4.8 MAF out of the 7.2 MAF total that was allocated to Punjab[7].

Punjab refused the demand of Haryana on the basis of the Riparian principle and decided to claim the entire 7.2 MAF[7]. |

| 1981 | Mutual agreement between Punjab & Haryana | Both states agree on the reallocation of water from Punjab in December 1981 after the involvement of the Supreme Court of India, the Prime Minister, and the Chief Ministers of Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan[7]. |

| 1982 | Construction of the canal begins and is stopped shortly after | Construction of the 214km canal begins in Kapoori Village in Punjab[8].

This leads to severe unrest in Punjab as farmers were unsatisfied with the claims of Haryana and claimed that they would not have enough water for their agricultural needs. Severe political and social unrest in Punjab leads to the stoppage of the construction of the SYL canal. |

| 1996 | Haryana files with the Supreme Court of India | Haryana asks the court to intervene and direct Punjab to complete its portion of the SYL canal.

Punjab was not ready to accept the terms as the common people of Punjab were not in support. |

| 2002 & 2004 | The Supreme Court’s direction to Punjab | The Supreme Court directs Punjab on separate occasions to finish the construction of the canal[1]. |

| 2004 | Punjab Termination of Agreements Act | Punjab passes the “Punjab Termination of Agreements Act” in the legislature which states that they will terminate all previously set water-sharing agreements with the state of Haryana. Punjab claims that as a “Riparian” State it should not have to divert water from its state[5].

Haryana does not accept this agreement based on the idea that a state cannot go back on a bilateral promise that it has signed . |

| 2016 | Presidential Reference | The President of India pushes the issue onto the Supreme Court once again for legal referral. The Supreme Court declares that the “Termination of Agreements Act” was indeed unconstitutional[8]. |

| 2020 | Supreme Court Decision | Supreme Court directs the Chief Ministers of both states to renegotiate the terms of the agreement and settle the issue. The issue would also be mediated by the central government[8]. |

Tenure Arrangements: From the Indus River Treaty Onwards

Indus River Treaty

In 1947, the British Indian Empire was divided into India and Pakistan, creating an international status for the Indus river and its branches. India became the upper riparian state and Pakistan the lower riparian state[6]. The international status of the Indus river and its branches has had a major impact on both India and Pakistan, as it has defined their roles in the management of the river system. This has led to the development of several agreements and initiatives to ensure the sustainable use of the river[6].

The treaty established the Indus Water Commission, which was responsible for the distribution of water from the Indus River Basin. This commission was responsible for developing plans to ensure the equitable distribution of the basin's water. The treaty also set up a mechanism for resolving disputes between the two countries in cases of water usage[6]. The Indus River Treaty of 1960 was a milestone in the history of India and Pakistan and its successful implementation has contributed to peace and stability in the region.

The Indus Waters Treaty of 1960 is a landmark international agreement between India and Pakistan which saw the water of the Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas rivers handed over to India[6]. India was given exclusive rights to use the water of the Chenab and Jhelum rivers, while Pakistan was granted the water of the Indus river's western branches[6]. In addition, the treaty included provisions for India to construct storage and hydroelectric projects on the western rivers[6]. The agreement was brokered by the World Bank and has been seen as a successful example of cooperation between the two countries.

Punjab Termination of Agreements Bill

In 2004, the Punjab Termination of Agreements Bill was passed in the Punjab Legislative Assembly, making the Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal (SYL) non-operational[3]. This was done to protect the rights of the state of Punjab over the River Sutlej and its resources, as it was felt that the Union Government had not been acting in the best interests of the state[3]. This bill was met with strong opposition from the state of Haryana, as they felt that they were being deprived of their rightful share of the resources from the river[3].

The Punjab Termination of Agreements Bill was a drastic move that caused a great deal of tension between the two states and did not provide a long-term solution to the conflict. To resolve this issue, it is necessary to look for a more sustainable solution that will benefit both states and the local community. As discussed, community forestry can provide an effective solution to this problem. By involving the local community in the decision-making process, they can help to ensure that both states are getting a fair share of the resources from the river and that the resources are managed in a way that is beneficial to the environment and the people who depend on it. This could help to resolve the conflict between the two states and ensure that the resources from the River Sutlej are managed fairly and sustainably.

In conclusion, the Punjab Termination of Agreements Bill of 2004 was a drastic move that did not provide a long-term solution to the conflict between the states of Haryana and Punjab over the resources of the River Sutlej. Community forestry can provide a more sustainable solution to this problem by involving the local community in the decision-making process and ensuring that both states are getting a fair share of the resources from the river. This could help to resolve the conflict between the two states and ensure that the resources from the River Sutlej are managed in fairness and sustainably.

Institutional/Administrative arrangements

The institutional arrangements surrounding the SYL Canal in Punjab, India from a community forestry perspective involve the Central and State Governments, local administrations, and non-governmental organizations.

The State of Punjab has undertaken unprecedented institutional and administrative arrangements to ensure the timely completion of the SYL canal. In order to ensure the successful implementation of the project, the government has created a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) - the ‘Punjab SYL Canal Project Authority (PSCA)’ - to take up the task of implementing the SYL Canal in Punjab[4]. The PSCA will be responsible for the overall planning, coordination and supervision of the project. It will ensure that the project is completed in a timely and efficient manner. The Punjab Government has also set up a Special Task Force (STF) to coordinate with the PSCA to ensure the timely completion of the SYL Canal works. The STF will also coordinate with the Central Water Commission (CWC) for technical advice on the implementation of the project. The Punjab Government has also created a ‘SYL Project Monitoring Cell’ to monitor the progress of the SYL Canal works. It will track the progress of the project and ensure that the deadlines are met. The government has also set up an ‘Inter-State Water Disputes Tribunal’ to resolve any disputes between the states of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan[4].

The local administrations are responsible for the implementation of the project at the local level, and for the monitoring and evaluation of the project. Non-governmental organizations are involved in the process and are responsible for providing support and guidance to local communities, and for helping to ensure that the project is implemented in a sustainable and equitable manner. The main reporting systems include reports from the Central and State Governments, local administrations, and non-governmental organizations. These reports are reviewed by the Central Government to ensure that the project is being implemented in accordance with the plans and goals.

Affected Stakeholders

User Groups of the SYL Canal include farmers, industrialists, and other users. These groups have a medium amount of relative power. Their primary objective is to ensure that their water rights are respected and that the water supply is sufficient. The livelihoods of these groups depend on water availability and access. The user groups of the SYL Canal have also advocated for the protection of local forests in order to ensure a sustainable water supply. In addition to respecting their water rights, they have raised awareness of the importance of community forestry initiatives, such as reforestation, agroforestry, and watershed protection. Through these efforts, they are hoping to ensure the long-term availability of freshwater. These statements are backed by evidence found in the Rodell et al. (2009) study regarding NASA’s GRACE program[3].

The government of Punjab has expressed its opposition to the formation of the SYL Canal, citing concerns that diverting water would cause hardship on its people and decrease agricultural activity. To ensure an equitable and sustainable water supply, the government has joined forces with the user groups of the SYL Canal to advocate for the protection of local forests and implementation of community forestry initiatives. This partnership has been essential in helping to balance the needs of the people of Punjab with the demands of the SYL Canal[6].

Punjabi farmers have the highest relative power of the user groups due to their direct connection to their land, water rights, and livelihoods. To protect these interests, the people of Punjab have taken to the streets in protest and even committed acts of civil disobedience. As a result, the government of Punjab has joined forces with these user groups to protect the people’s land, water rights, and livelihoods. The negative effects are also seen as farmers are committing suicides due to failure of pumps drying of wells, and when they are unable to get bore wells installed due to high prices[9]. The affected stakeholders have had their livelihoods negatively impacted for over 40 year, with evidence seen in Operation Kontakt, a program launched by the Russian KGB in Punjab[2].

Interested Stakeholders

State of Haryana

The Haryana government is continuously demanding increase in their share of water. The Haryana government will directly benefit from the completion of the SYL canal as they will be drastically increasing water intake from the Ravi River. This will mean more water for agricultural uses[10].

Relative power: High

Government of India

India’s highest level of government is the federal government. Therefore, water sharing activities of states is over-watched by the government of India. The role they play is to mediate the conflict between the two states[9].

Relative power: High

Supreme Court

A tribunal presided over by a judge from the supreme court is tasked with hearing the claims of Punjab and Haryana about the distribution of water. When laws relating to the usage of water are passed, the supreme court ensures that both states are functioning in accordance with the constitution. When it comes to issuing judgments over the usage of water, the Supreme Court also ensures that they are fair in judgement[6].

Relative power: High

World Bank

David E. Lilienthal, a World Bank representative, visited the disputed area and suggested using the World Bank to help with the Indus river negotiations, which was accepted by both nations. The economic worth of the pact and its political sway inside it are of interest to the bank. This authority is demonstrated in the annex, which specifies that the bank's president may propose a candidate to serve as the arbitration's umpire in the event that India or Pakistan are unable to reach terms. This influence has the potential to draw the power of abuse[11].

Relative power: Medium

Critical issues caused by the SYL Canal

The critical issues related to the Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) canal and the severe water crisis in Punjab are a result of the state's rapid population growth and the over-exploitation of its natural resources. In the past decade, groundwater depletion in north-western India has exceeded over 150 percent, especially in the major crop-producing states such as Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. This has been due to the demand for food, land, and water resources which have led to an unsustainable utilization of natural resources[4]. In addition, crop production in Punjab is growing at a rapid rate, leading to an expansion of cropland for wheat and paddy[12]. This further emphasizing the water crisis in the state as 79% of its underground water resources are being over-exploited[12].

The SYL canal crisis has been a major concern for Punjab for the past few years due to the ongoing dispute between Punjab and Haryana over the river water. The Supreme Court of India decreed in 2002 that the construction of the Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) canal be completed and that the water should be shared between the two states[5]. This has been a source of unrest in the state as Punjab is already facing an acute water crisis and the state is concerned that it will be forced to share its already scarce water resources.

To mitigate the water crisis and address the SYL canal crisis, the state of Punjab needs to focus on implementing effective water management strategies. This includes the implementation of efficient water conservation and harvesting techniques, the regulation of groundwater abstraction, and the adoption of water-saving irrigation techniques. In addition, the state should focus on developing new sources of water such as harvesting rainwater and recharging groundwater. This will help ensure that the state's water resources are used sustainably and will help ensure that the dispute over the SYL canal is resolved fairly.

To conclude, the water crisis in Punjab and the SYL canal crisis are a result of the state's rapid population growth and the over-exploitation of its natural resources. To mitigate these critical issues, the state needs to focus on implementing effective water management strategies that focus on conservation, harvesting, and efficient irrigation techniques.

Assessment of Punjab & Haryana's government roles

The SYL canal dispute between the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana has been largely managed by the Indian government, with the Union Government and the Supreme Court playing important roles[3]. The Indian government has the greatest power in this dispute due to its authority to make final decisions and its control over the water-sharing activities of the state. The two states of Punjab and Haryana also have significant power, as their governments are the primary stakeholders and can influence the dispute. The Indian courts also have a significant amount of power, as they can enforce the decisions made by the government[13]. The farmers in both states are also major social players in this dispute, though they have limited power due to their limited resources and lack of representation in decision-making processes.

The success or failure of the Indian government in managing the SYL canal dispute can be evaluated by looking at the outcomes of their interventions. The government has been successful in getting the two states to agree on a resolution and in enforcing the decisions made by the courts. They have also been successful in ensuring that the farmers’ voices are heard and that their resources are taken into account in the decision-making process. On the other hand, the government has been less successful in ensuring that the water-sharing activities of the state are managed fairly. This has led to an unequal distribution of resources, which has caused a great deal of discontent among the farmers in both states.

Overall, the Indian government has had some successes and some failures in managing the SYL canal dispute. They have been successful in getting the two states to agree on a resolution and in ensuring that the farmers’ voices are heard. However, they have been less successful in ensuring that the water-sharing activities of the state are managed fairly. To improve their success rate, the government needs to increase its focus on ensuring that water is shared fairly between the two states. Additionally, they need to ensure that the farmers’ resources are taken into account in the decision-making process. Only then will the Indian government be able to truly assess its success or failure in managing the SYL canal dispute.

Future Recommendations

Reforestation is an option for combating the damage caused by the SYL Canal in Punjab, India. This involves planting trees to create a more diverse and resilient landscape, which can help reduce the impact of water diversion and improve the local environment. Planting trees can help to restore the area's natural vegetation and restore the natural water cycle by increasing the amount of water retained in the soil and reducing the amount of water lost to runoff. Reforestation can also help to reduce soil erosion, improve air quality, and provide wildlife habitat. Additionally, it can provide an economic boost to local communities by providing timber, fuel, and other resources.

Agroforestry is another cost-effective and sustainable solution that can help Punjabi farmers reduce the effects of underground water depletion. This practice involves integrating trees with agricultural practices to promote sustainable production and reduce water diversion. This could involve planting trees on hillsides to reduce soil erosion, creating windbreaks to reduce evaporation, and planting trees in fields to reduce water runoff. Planting trees can help to improve the water-holding capacity of the soil, reduce the amount of water lost to runoff, and increase the amount of water available to crops. Additionally, agroforestry can help to reduce the amount of water needed for irrigation, improve soil fertility, and provide shade and shelter for livestock[14].

The state of Punjab, which is facing the impact of the SYL Canal, can take various actions to protect its riparian rights and seek possible reparations. These actions can include engaging with local, state, and federal authorities to raise awareness and advocate for a resolution, building coalitions with other affected stakeholders and applying international pressure, and collaborating with non-governmental organizations on community forestry initiatives that promote sustainable resource management and support local communities. By taking these steps, Punjab can work towards securing its riparian rights and obtaining reparations for the SYL Canal[9].

Eco-tourism is a potential option for the SYL canal area. Developing hiking trails, bird-watching sites, and other outdoor attractions could increase the area's appeal and generate income for local communities. Water conservation measures could also be implemented, such as constructing water catchment systems, installing rainwater harvesting systems, and promoting water-saving practices. Finally, community education is essential to raise awareness and promote sustainability, which could involve organizing seminars, workshops, and other activities. Together, these options could help protect the SYL canal and the surrounding area.

Conclusion

Upon final review, the complexity of the SYL canal dispute is understood through the sheer amount of time that it has been ongoing. The canal has, thus, been the subject of much controversy since its inception, with the livelihoods of local residents at stake. Through a better understanding of the issues faced by affected stakeholders as well as the rightsholders of the land, one can understand how climate change is affecting the livelihoods of the common farmers and people of Northern India[7]. Despite having such an important significance for the people of Punjab and Haryana, the SYL dispute remains unsolved as the Supreme Court of India and other negotiating parties are unable to come up with a solution to benefit people on both sides.

As studied by NASA in 2009, groundwater depletion in Northern India is at an all-time high. The reallocation of water away from Punjab via the SYL Canal has the potential to cause complete desertification of the area [4]. As the livelihoods of millions of farmers in the Punjab region are dependent on wheat and paddy farming in the largely agricultural state, fears of losing their water supplies have led to local communities protesting against the water diversion and the negative impacts it may have on the environment and the local economy. Water depletion would especially lead to the destruction of natural habitats and the displacement of local wildlife amongst other factors[4]. Additionally, the lack of water has caused a decrease in agricultural productivity in the region, leading to economic hardship for local communities[7].

Although Haryana requires water as an agricultural state itself, the central government must work towards allocating water from other sources as well[15]. It is well known that water flowing from the Yamuna River into Rajasthan is not being used to its full potential[7]. The states must look towards a resolution which is favorable towards all the affected parties and ensures that it will not cost external stress to the environment and diminish the living quality of the people of either state.

Through the recommendations listed above, the state of Punjab can work towards a resolution that ensures they are able to remain a vital and functioning agricultural state which is also responsible for some of the highest per acre investments by farmers in the world[7][9]. To reduce over-exploitation of its resources, the state must find well researched and reliable techniques to support its local people[16].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Khurana, I. (2006). Politics and litigation play havoc: Sutlej Yamuna Link Canal. Economic and Political Weekly, 41(7), 608–611. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4417835

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Swain, A. (2017). Water insecurity in the Indus Basin: The costs of noncooperation. In Z. Adeel, R.G. Wirsing (Eds.), Imagining Industan, (pp. 37-48). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32845-4_3

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Ranjan, A. (2019). Inter-State river water disputes in India: A study of water disputes between Punjab and Haryana. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 65(4), 830-847 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Rodell, M., Velicogna, I., & Famiglietti, J. S. (2009), Satellite‐based estimates of groundwater depletion in India, Nature, 460(7258), 999–1002. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/satellite-based-estimates-groundwater-depletion/docview/204568110/se-2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":7" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Singh, G. (2002). Punjab waters: SYL Canal. Institute of Sikh Studies.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Gill, S. S. (2016). Water crisis in Punjab and Haryana: Politics of Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(50), 37-41. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/water-crisis-punjab-haryana-politics-sutlej/docview/2153696517/se-2

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Mann, V. S. (2003). Troubled waters of Punjab. Allied Publishers.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mangat, H. S. (2016). Water war between Punjab and Haryana: A geographical insight. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(50), 52–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44165964

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Arora, M. (2011). Sharing of river water and political interests dispute over Sutlej Yamuna Link Canal between Punjab and Haryana. [Doctoral Dissertation, Jawaharlal Nehru University]. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/121682 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":9" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Ranjit, S. G. (2017). Water use scenario in Punjab: Beyond the Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal. Economic and Political Weekly. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/water-use-scenario-punjab-beyond-sutlej-yamuna/docview/2153692210/se-2

- ↑ Patel, B. N. (2017). Why does World Bank want to broker Indus water talks between India and Pakistan. The Indian Express. Retrieved from http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/why-does-world-bank-want-to-broker-indus-water-treaty-talks-between-india-and-pakistan-846306/

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Shivani, M. S., Srivastava, S., & Singh, A. (2022). Critical analysis of hydrological mass variations of northwest India. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1032(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1032/1/012032

- ↑ Ballabh, V. (2008). Governance of water: Institutional alternatives and political economy. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.ca/books?id=lVXDfcxDK7YC&pg=PA179&redir_esc=y

- ↑ Verma, K. C. (1993). Soil strengthening of Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal powerhouses in Punjab, India. Third international conference on case histories in geotechnical engineering, 7.42, 1119-1123. https://core.ac.uk/reader/229074610

- ↑ Planning Commission, Government of India (2009). Haryana development report. Academic Foundation. http://14.139.60.153/bitstream/123456789/2978/1/Haryana%20Development%20Report%202009.pdf

- ↑ Singh, M. (2002). Punjab river waters. News & Views, 117(1), 54.

| Theme: Community Forestry | |

| Country: India | |

| Province/Prefecture: Punjab & Haryana | |

This conservation resource was created by Yoovi Vasudev, Ahsan Khan, Bhavjeet Khangura, Navin Johal. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |