Course:FRST370/Projects/Forest Resource Management in Harrop-Procter Community Forest, BC, Canada

Harrop-Procter Community Forest (HPCF) is located in the small communities of Harrop and Procter in southwestern British Columbia (BC), Canada[1]. It covers 11,300 hectares of Provincial Forest Crown land on the West Arm of Kootenay Lake[2]. Harrop-Procter has a twenty-three year history of environmental activism prior to its official designation, as residents struggled to protect local watersheds and have a voice in logging practices[3]. Through a community forest agreement (CFA) with the Ministry of Forests in 1999, they have managed the forests to produce ecologically responsible wood products and non-timber forest products[2]. HPCF’s two management groups, Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society and Harrop-Procter Community Co-operative, work together to implement an ecosystem-based approach to forest management, as well as expand local employment[3].

Description

The Communities of Harrop and Procter

The small communities of Harrop and Procter are about thirty kilometers northeast of Nelson in the West Kootenay region of BC [1]. Accessible only by cable ferry, the relatively isolated communities are also rural, with a majority of the 245 homes built on parcels of land between 0.50 and 30.0 acres[1]. The population of Harrop and Procter includes 650 full time residents comprised of many young people [2]. The majority of the population is under 55 years old and youth make up the largest single component of the population[1]. The community has several hobby farms, recreation operators, and two bed-and-breakfasts[1]. Procter is unincorporated with a general store, two churches and a community hall[1]. Harrop-Procter contains many people with forestry backgrounds, such as Registered Professional Foresters and business people who are willing to volunteer, sit on boards and fill staff positions, which was useful in the formation of the community forest[4].

Harrop-Procter Community Forest Land Base

HPCF is located outside of Harrop and Procter with a land base covering 11,300 hectares of Provincial Forest Crown land[2]. The area is bordered on the north and east by Kootenay Lake, and on the west and south by the West Arm Wilderness Park[1]. HPCF includes Harrop, Slater, Narrows, Procter, and Irvine Creeks, as well as numerous smaller drainages[5]. The mountains and steep valleys vary in elevations ranging from 523m at lake level and 2400m in the alpine[1]. The forests are very diverse and productive containing numerous tree species, including Douglas-fir, western larch, paper birch, western white pine, Engelmann spruce, western red cedar, and western hemlock[1]. Fires in 1901 have resulted in an extensive forest of seral species[1]. There are a few stands over 300 years old and old growth often in riparian zones that were missed by the last fires[1]. HPCF is classified as interior rainforest as part of the Southern Columbian Mountain Ecosection and includes several biogeoclimatic zones (ICH 2, ESSF, and AT)[1]. Prior to the establishment of HPCF, the forests surrounding Harrop-Procter had not been logged for almost two centuries[2].

History of Public Participation to Achieve Community Forest Tenure

Harrop-Procter has a long history of involvement in land-use issues, as residents shared a concern for local forestry. It is a story of conflict, community turmoil, and reclamation. As far back as 1976, residents were concerned about clearcut logging after being exposed to logging practices that degraded stream systems[3]. Harrop-Procter residents had an interest in forest management and its effect on the beauty of Kootenay Lake[3]. Bruce Fraser of Selkirk College, Castlegar, in a process called 'Forest Planning for the West Arm of Kootenay Lake' consulted residents and listened to their concerns about the current watershed management practices[1]. Important points were raised at this time, establishing the collective spirit of the community. Residents were willing to work with Forest Service given that there would be an effort to seek alternatives to extensive clear cutting and high road impact[1]. In 1977, Fraser published a report to the Ministry of Forests suggesting public involvement in the harvesting process and the revision of a planned road system above Harrop[1]. Eight years later, a resident discovered that the Ministry of Forests unilaterally released a logging plan on nearby Lasca Creek after continued rumours of logging activity[1]. This plan included a main-haul road through the westerly slope of Harrop Creek irrespective of Fraser’s recommendations[1]. In attempts to communicate with the Minister of Forests, a contact committee was chosen at a public meeting to send letters[3]. The first letter reads, "we insist that we be given time to study the proposals in detail, without the fear of the bulldozer hanging over our heads; and that the spirit of the previous Cooperative resource development planning be reborn... Sir, the citizens of the area have many ideas, and we urge you to allow us to share them with you in the formulation of logging plans"[1]. In a follow-up letter, two weeks later, the contact committee wrote, "we have been told during discussions with your representatives that this project is going through - that a portion of the logging haulage road will be built in the Harrop Creek Watershed [...] We refuse to give last- minute sanctions to a pre-arranged packaged plan developed in isolation from our community"[1].

The Kootenay Lake Forest District (KLFD) declined an alternate road location and doubted the legitimacy of the contact committee to speak for the community[1]. The Harrop-Procter community, feeling ignored, called a public meeting in Harrop Hall on September 10, 1984 and formed the Harrop-Procter Watershed and Community Protection Committee[3]. This group met with the KLFD office until the fall of 1986 in attempts to establish mutual respect and contribute their perspectives into forest management[1]. By 1991, Harrop-procter still lacked a long term plan. In the Winter of 1992, a Procter resident thought that the Federal Government’s invitation for proposals for a Model Forest was an appropriate opportunity to form a partnership with various levels of government[1]. Although a group of community volunteers produced a progressive proposal, it was eventually rejected[1]. In the spring of 1992, The Ministry of Forests commissioned a new survey of public the concerns in Harrop-Procter which reads:

"The residents' message to the Ministry of Forests is 'reduce the cut', 'don't clearcut', 'manage for water and viewscape', and 'stay well back from creeks and wet areas, unless using single-tree selection systems, with very light equipment or horses' [and] 'Above all, listen to the people, they hold the ultimate veto'"[1].

The Lasca Creek operation caused stress and confrontation until 1995 when the BC government decided to create the West Arm Wilderness Park to protect the Lasca Creek area[3]. However, Harrop-Procter watersheds were not included and logging above the town appeared imminent[3]. A series of community meetings with dedicated residents led to the Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society (the Society) obtaining official society status in 1996[3]. The Society became eligible to apply for a community forest licence under the New Opportunities for Wood Program that same year but was not successful in obtaining tenure[1]. Persistent volunteers conducted community fundraisers and applied for funding from private philanthropic foundations[3]. This funding was used to work with the Silva Forest Foundation to create an ecosystem-based plan for the watersheds surrounding the Harrop-Procter corridor[3]. The Society’s new goal was to use innovative harvesting practices in one of the first area-based tenures in BC[3]. A publicity campaign with a door-to-door membership technique resulted in more than 60% of adult residents of Harrop-Procter joining the society[3]. In 1997, the Harrop-Procter community was galvanized when Forests Minister David Zirnhelt gave Harrop-Procter a personal invitation to submit a proposal for a Community Forest Pilot Agreement[1]. The proposal was a culmination of months of hard work by the community and protects a broad range of values[1]. It was an impressive proposal that addressed sustainable forestry and long range economic development[1]. In July of 1999, Harrop-Procter was awarded a five year licence with an allowable annual cut (AAC) of 2,600 cubic metres[2]. This story reflects the difficulties many communities face globally to have their voices heard in forest management. It shows the degree of intensity and long duration of time a community may have to fight to obtain legal rights to manage valuable environmental resources.

Tenure arrangements

HPCF currently holds a community forest agreement (CFA). This is an area-based forest licence managed by a local people for the benefit of the whole community.

Changes in Tenure

HPCF obtained their first community forest tenure under the Community Forest Pilot program[4]. This program allowed rural communities and First Nations to obtain land tenures that were more suitable for their needs[4]. Before 1988, the tenures granted to communities were standard industrial tenure arrangements designed for corporations[4]. Harrop-Procter was one of 11 communities offered Community Forest Pilot Agreements out of more than 100 communities that expressed interest[4]. HPCF initially had an AAC of 2,603 m3, the lowest harvest volume of community-held forest lands in BC[4]. Additionally, the Harrop-Procter Community Forest Pilot Agreement was the first forest license in BC to include the commercial harvest of non-timber forest products (NTFPs)[6]. After two-five-year licences, The Ministry of Forests abolished five-year Community Forest Agreements in 2008[2]. HPCF received a twenty-five year licence which is renewable every ten years[2]. In 2007, there was a temporary increase in AAC to remove beetle-infested lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta)[2]. In 2012, while creating a secondary management plan, HPCF reviewed their AAC and consulted with the community regarding a potential AAC increase[5]. With support from the community the new AAC was set at 10,000 m3 in 2013[2]. This remains a relatively low AAC and according to HPCF’s own analysis, they can harvest sustainability for another forty years under this volume[2]. HPCF has timber harvesting as an integral requirement of their tenure agreement[2]. However, the Ministry of Forests does not require a community forest to directly manage forestry operations and forest management may be subcontracted to another company. [2]Unlike Logan Lake Community Forest, HPCF has chosen to directly manage forestry operations and forest management, although this is not a requirement of the tenure[2]. This has resulted in more control in local people.

Administrative Arrangements

HPCF has an effective internal governance structure comprised of the Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society (the Society) and the Harrop-Procter Community Co-operative (the Co-op). The Society is dedicated to research and education, and the Co-op oversees business[2]. The two boards share half of their directors to provide a connection between the organizations[4]. Public meetings and community newsletters are used for education information and updates in the community forest[1]. For example, the Spring 2018 newsletter written by both the Society and the Co-op contained updates regarding future fundraising events, the rate of activity in the mill, changes in employment personnel, donations to date, and details of various projects[7].

Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society

The Society has a long history with its beginnings as a persistent committee in 1982 fighting to preserve local watersheds[3]. The group was registered in 1996 and submitted the Community Forest Pilot Proposal in 1998[1]. Its main role is stewardship and is overseen by a board of directors that is elected from membership[2]. The Society is responsible for overseeing the Co-op’s activities, water monitoring, education, and outreach[3]. Membership is open to all people and has 37 members as of 2014. The Society meets quarterly to discuss upcoming issues and events[2].

The Society’s Mission Statement[3]:

- The promotion of the preservation and protection of all watersheds in the community and the assurance of a consistent quantity and quality of water.

- The development of public forests in the Harrop-Procter area according to site-sensitive ecologically based forestry practices; modeled on Silva Forest Foundation planning process.

- To promote and encourage locally based employment available through the development of public forest lands.

- Dedicated to ecosystem research, public education and sustainable rural communities.

Harrop-Procter Community Co-operative

Formed in 1999 to hold the community forest agreement, the Co-op is the business arm which manages forest operations and pursues economic development[2]. HPCF decided to operate with a cooperative model as it was deemed the best corporate structure for conducting community business[1]. It allows for public participation while maintaining accountability[1]. The Co-op is overseen by a board of directors that are elected from the membership[8]. Membership is for life and only open to the residents of Harrop and Procter[2]. As of 2014, The Co-op has 137 members[2]. It has several communities including volunteer directors and interested community members[9]. It has a forest manager, office coordinator and bookkeeper. The Co-op is a “not-for-profit” organization but has a subsidiary company called Harrop-Procter Forest Products (HPFP)[9]. To add value to logging, HPFP create cedar and Douglas-fir lumber and sell to a primarily local retail market[9]. They produce a range of wood products including cedar siding, Douglas-fir interior trim and flooring, and custom cut timbers[10]. The Co-op’s mission state is to “develop public forests in the Harrop-Procter area according to site sensitive, ecologically based forestry practices which are modeled on Silva Forest Foundation planning and approved by the Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society” and to “stimulate locally based employment from the Harrop-Procter Forest lands which is ecologically sustainable, and socially and economically equitable”[9].

Aims and Intentions of Harrop-Procter Community Forest

The core values of HPCF were declared in the 1990’s initial community forestry proposal and the corresponding management goals, objectives, and strategies have been reinforced in following management plans. The main objective and motivator for their forestry initiatives is the protection of domestic water sources[1]. The community experienced stream degradation from forest mismanagement in the past and believe they can manage the local watershed more effectively than existing forest companies[4]. Their management philosophy is influenced by ecosystem-based conservation planning described as ‘‘a method of ecosystem protection, maintenance, restoration, and human use that, as the first priority, maintains or restores natural ecological integrity—including biological diversity—across the full range of spatial and temporal scales’’[11]. An updated management plan from 2012, outlines the resource management goals of HPCF including environmental, social and economic, and outreach goals. Environmental goals include the maintenance of a fully functioning forest, protection of biodiversity, enhancement of ecosystem resilience against climate change, and continual sustainability of timber and NTFPs[5]. HPCF’s initiatives to enhance the social and economic dimensions of the community include providing recreation, wildcrafting, local employment, economic diversification, and opportunities for meaningful community participation[5]. Outreach, education, and research goals support research and educational opportunities related to resource stewardship, alternative silviculture systems, and climate change adaptation[5].

Resource Management Objectives

HPCF manages their forest for several values that enhance the community’s ecology and economy. Timber objectives include sustainable harvest rates and the creation of a diverse range of wood products, including sawlogs, peelers, building logs, poles, firewood, pulp, and specialty wood products[10]. Additionally, their vision is to have few unprocessed logs leave the community and to incorporate value added-forestry through local milling and sorting on the stump[4]. Water objectives aim to protect water quality, quantity, and timing of flow[5]. Biodiversity objectives conserve forest structure and biological legacies when planning and implementing forestry activities, as well as identify and protect threatened and endangered ecosystems[5]. Soil and forest health protection is also an important objective to maintain the productivity and resilience of the forest[5]. HPCF has wildfire protection objectives to improve fire resilience and lower the risk of catastrophic wildfires[12]. The maintenance of visual beauty is a goal while harvesting and road building[5]. HPCF aims to improve recreation and NTFP opportunities through the community forest[1].

Successes of Harrop-Procter Community Forest

Community Cohesion

Given the grueling fight by the community to protect their watershed, achieving community forest tenure was a significant victory. Ultimately, strong local support, inclusivity, and participation resulted in their success[4]. In the development of the Community Pilot Proposal, local organizers twice went door-to-door to discuss their plans with every local resident, once during the proposal development stage and again after their proposal was approved three years later[1][4]. Meetings were also held with First Nations representatives[1]. During that process, the Society had support from 359 adults in community of 450 adult residents[4]. HPCF achieved a remarkable level of community endorsement, despite the plan to log in domestic watersheds[13]. It was estimated that over $100,000 worth of volunteer time and services was required to develop the community forestry proposal alone[4]. Ongoing volunteer support fuels HPCF with over 350 volunteer hours each month[4]. In a community survey, 23 out of 28 members agreed HPCF was effectively managing the forest[2].

Timber Management

Forest operations have proven successful, as a majority of harvesting has been high-retention single-tree or small group selection with the retention of 60% of canopy trees[5]. Logging techniques attempt to mimic natural forest disturbances to maintain ecosystem resilience[5]. In a 2008 audit that examined HPCF’s planning, field activities and obligations of timber harvesting, road construction, silviculture, and fire protection showed compliance and success in meeting requirements of the Forest and Range Practices Act and the Wildfire Act[14]. HPCF is the only community forest in BC whose wood is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council[2]. Another large success is the high number of jobs provided by the local sawmill at around seven times the number of jobs per cubic metre than the provincial average[15]. The Co-op was able to grow in the last five years even in a poor economic climate for the industry[10].

Social Learning

Participants in the community forest achieved skills and knowledge through social learning, the understanding that goes beyond the individual to wider social units through social interactions[2]. Most volunteers began with limited forestry knowledge but learned as they participated in the community forest[8]. Members achieved knowledge on topics including forest ecology and watershed function, as well as technical skills[2]. Learning occurs in activities such as meetings, data collection, advocacy, awareness raising, field tours, fundraising, resource harvesting, monitoring, and critical reflection on activities[2]. This social learning allowed HPCF to evolve and become more successful.

Donations

A mandate of the Co-op is to donate wood products to community organizations to benefit the immediate community[10]. The board of directors passed a motion last year that sets such donations at $10,000 annually[10]. HPCF has provided numerous donations the community, including a fishing platform to the West Arm Outdoors Club, a wheelchair ramp to the Harrop & District Community Centre Society, and benches to Sunshine Bay Park[16]. In 2014, HPCF donated $4500.00 for the wooden playground at Procter Schoolhouse[17].

Robin Hood Memorial Award

In June 2017, the Co-op won the Robin Hood Memorial award and $10,000 from the BC Community Forest Association[7]. This prize is given annually by the Ministry of Forests to an exemplary community forest[15]. HPCF won due to its strong leadership in climate change adaptation, successful harvesting in sensitive viewscapes, and the operation of the sawmill[15]. This award is recognition of their success by the Province. The Co-op is using the money to support a permanent fund that will annually award a Grade 12 student a $1000 Scholarship award for their post-secondary education[7]. The creation of a scholarship demonstrates HPCF’s dedication to education.

Outreach

In line with HPCF’s outreach, education, and research goals, the Society is supporting a study by the Selkirk College School of Environment and Geomatics that explores the possibility of retention ponds being established within the community forest[7]. In August 2015, UBC Masters of Sustainable Forest Management students visited in the community forest[16]. Additionally, HPCF staff and forest directors give presentations on community forestry and participate in international conferences[3].

Community Conflicts and Challenges

Over the course Harrop-Procter’s community forest tenure, challenges have arisen that have led to an increasingly more efficient forestry business. Refocusing initiatives and professionalizing the community forest has narrowed participation and learning opportunities for members of HPCF[2]. Additionally, climate change is an irrefutable challenge with implications for forest management.

Sunshine Bay Botanicals

The development of NTFPs is an objective of HPCF that has posed a challenge. In 2001, Sunshine Bay Botanicals was established as a division of the Co-op with a goal to develop NTFPs[8]. Members cultivated herbs and plants for a line of medicinal and culinary botanicals[6]. This was a unique venture that for some years enjoyed success[8]. However, the extensive labour and supply costs involved with NTFP production and processing resulted in Sunshine Bay Botanicals closure in 2007[8]. The community response was torn. Some members saw the project as innovative and prosperous, while others thought it drained volunteer time and organizational resources[8]. The closure of the project allowed HPCF to further concentrate on the timber business in its early stages and increased funds for forestry operations[8]. Ultimately, HPCF recognized what was the most effective and appropriate decision for the organization at the time. However, Sunshine Bay Botanicals provided volunteer opportunities to those not interested in timber products and some desire the project to get taken up again[8]. A HPCF member states, “maybe now that they [...] have the logging down and the community has settled down a little bit, maybe they could try the value-added stuff again”[8]. Sunshine Bay Botanicals closure resulted in lost volunteers and has narrowed the range of activities available to members[2].

Shift from Volunteer to Paid Positions

Over time, Harrop-Procter had increasing financial and legal obligations, leading to the shift of participants in volunteer to paid positions[2]. The increased number of permanent professional staff has reduced the decision-making power of the membership of the community forest[8]. HPCF is well organized but perceived as less inclusive by members. A HPCF participant observed, “it is sort of a jelled smaller group now that does almost everything, those that have jobs and are getting paid are just a few and they kind of run the whole thing. I don’t feel like anything really is open up to the community"[2]. The gradual professionalization has lessened participation opportunities for members and has caused some exclusion in the community forest[8].

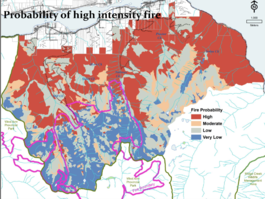

Climate Change

In this era of environmental uncertainty, HPCF recognizes the need to adapt community forest initiatives and forest management practices to prepare for climate change impacts. Climate projections indicate that that summer's will be warmer and up to 30% drier in the BC southern interior[12]. Extreme weather events are expected to increase in frequency and magnitude[5]. Insect and disease epidemics are also projected to increase, signaling a need to shift to adaptive forest management[12]. In the 1990s, climate change was not a major consideration to HPCF[12]. This changed in August of 2003 when the Kutetl wildfire had grown to several thousand hectares and began to burn down Harrop Creek[12]. With poor access for firefighters and no rain, evacuation plans were in put in place[12]. Fortunately, a month later it rained and by the end of September the fire was extinguished[12]. Wildfire protection became a higher priority initiative and the risks associated with large unbroken tracts of mature coniferous forest were highlighted[12]. HPCF has taken some practical steps for proactive fire management, including using regeneration harvest methods to transition stands away from cedar and hemlock forests to Douglas-fir and larch forest that are better adapted to fire and drier climate[5]. Additionally, HPCF has been planting seedlings grown from seeds collected from a dryer area to increase ecosystem resilience to summer drought and wildfire[12]. HPCF has targeted vulnerable forests and uniformly dense coniferous forests for commercial logging[12]. Climate change poses a serious challenge for the community forest and requires strategic and adaptive forest management.

Stakeholders

There are many individuals, groups, and entities involved in the land of HPCF with varying degrees of interest, investment, and power.

Affected

The Society is comprised of 37 members and 9 board members that are affected stakeholders in the land with a mission to protect the forest and watershed[8]. The Co-op has 137 members, 12 board members, and 4 full time employees for the saw mill whose livelihoods depend on the condition of the forest[8]. The formation of these groups has given Harrop-Procter residents increased power to manage the landscape according to local values. Eight hundred residents obtain their water from the streams in the community forest[14]. All water users of the domestic watershed are affected stakeholders, as their wellbeing depends on a functioning ecosystem. Ktunaxa and Sinixt First Nations are affected stakeholders whose customary rights entail hunting in the HPCF area[8]. They are affected as they never gave up their underlying claim. In the creation of the Community Forest Pilot Proposal, the Sinixt provided a map depicting areas of medium and high cultural priority and provided a letter of support for the community forest proposal[1]. Ramona Faust was directly involved with HPCF from 1996 until 2006 and is currently the elected representative of Area E of the Regional District of Central Kootenay[18]. As a resident of Procter, she is an affected stakeholder with higher power to influence policy and forest management outcomes[18].

Interested

The Ministry of Forests is an interested stakeholder with high power to influence forest management through policy, tenure type, and tenure length[2]. Some philanthropic foundations supported HPCF and provided a source of funding that was integral in the community forest’s initiation and early operations[3]. Some external funding was used to collaborate with the Silva Forest Foundation to create the ecosystem-based plan which guides HPCF[3]. Additionally, the Columbia Basin Trust provided funds which contributed to the labour costs associated with Sunshine Bay Botanicals[8]. Although these organizations provided support to HPCF, they are not personally affected by activities in the watershed. Therefore, they are interested stakeholders. Local businesses are interested stakeholders which share HPCF’s concern for the economic value of the watershed[1]. Selkirk College and the University of British Columbia are interested stakeholders that have expressed interest in Harrop-Procter’s value for educational study[7].

Recommendations

Urban forestry is a method that could diversify the landscape and forestry industry in Harrop-Procter. The advancement of more higher quality parks, community gardens, green infrastructure or street greening can offer positive benefits that may not be given by timber focused community forest. For example, ecotourism can be be enhanced through improved public green spaces. When Creston Valley Forest Corporation installed 4 major hiking trails and produced attractive landscapes for tourism, they generated wealth without the damaging effects of logging[19]. Urban forestry is an exciting niche that would attract involvement from residents galvanized to improve the town for aesthetics, recreation, and physical health. If the members of HPCF could also have the power to shape these amenities it would drastically improve opportunities for new types of social learning. These projects could increase participation, as urban forestry is extremely collaborative and locally-orientated.

As climate change poses imminent and significant impacts on human wellbeing, urban forestry must be seen as a tool for the adaptation and mitigation of these effects. HPCF should consider urban forestry and the positive benefits of incorporating greenspaces to reduce climate change effects. For example, urban forestry can buffer the expected rise in year-round temperatures by providing cooling of the urban heat island effect, reducing local temperatures, shading public spaces, and lessening negative health impacts for the vulnerable. Climate models project year-round temperatures to increase by at least 2 - 5o C in the Harrop-Procter area[20]. Wildfires cause damage to the precious timber and affect human health through stress, and decreased air and water quality. Many studies have been conducted, confirming the ability of vegetation to reduce local ambient temperature by 2 - 4o C[21]. I recommend consideration on greenspace development in adaptive management plans in regard to climate change, as urban streets, parks, and green infrastructure have been proven to buffer the expected rise in year-round temperature. Urban forests can also be used to regulate water flow and excess rainfall, as soil is pervious and trees absorb water[22]. This is important for Harrop-Procter, as the area is projected to receive 10 - 25% more precipitation during the fall, winter, and spring in the upcoming years[20]. I recommend planting native evergreen species in areas where water management is needed, as they retain large amounts of rainwater and are quite drought tolerant[22]. I recommend HPCF expand into the sector of urban forestry. Ultimately, the goals of urban forestry and HPCF align, as both persist to increase community and ecosystem resilience.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society. (1999). Community Forest Pilot Agreement Proposal. Retrieved November 7, 2018, from http://www.hpcommunityforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/pilot_agree.pdf

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 Egunyu, F., Reed, M. G., & Sinclair, J. A. (2016). Learning through new approaches to forest governance: Evidence from Harrop-Procter community forest, Canada. Environmental Management, 57(4), 784-797. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0652-4

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Harrop-Procter Forest Products. (n.d.). The Harrop-Procter Watershed Protection Society. Retrieved November 5, 2018, from http://hpcommunityforest.org/about-hpwps/

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Anderson, N. G., & Horter, W. (2002, October). Connecting Lands and People in Community Forests in British Columbia. Dogwood Initiative. Retrieved November 7, 2018, from https://dogwoodbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Connecting-Lands-and-People_sm.pdf

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Harrop-Procter Community Co-operative. (2012). Management Plan #2. Retrieved November 5, 2018, from http://hpcommunityforest.org/hpcc/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ascher, A. (2004). Under the canopy: The gathering of mushrooms, berries and other forest materials is becoming a billion-dollar industry. Alternatives Journal, 30(3). Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/218736295?accountid=14656

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Harrop-Procter Forest Products. (2018). Community Forest News. Retrieved November 5, 2018, from http://hpcommunityforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Community-Forest-Newsletter-Spring-2018-v2.pdf

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 Egunyu, F. & Reed., M. (2017). Harrop-Procter Community Forest: Learning How to Manage Forest Resources at the Community Level. In Growing community forests: practice, research, and advocacy in Canada (pp. 160–179). Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Harrop-Procter Forest Products. (n.d.). The Harrop-Procter Community Co-operative. Retrieved November 5, 2018, from http://hpcommunityforest.org/hpcc/

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Rasch, V. (n.d.). Community control exemplifies small-scale forestry. Retrieved November 7, 2018, from https://kootenaybiz.com/forestry/article/community_control_exemplifies_small_scale_forestry

- ↑ Silva Forest Foundation. (2015). Definition and Principles of Ecosystem Based Conservation Planning. Retrieved from http://www.silvafor.org/assets/silva/PDF/EBCPDefinitionPrinciples.docx.pdf

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 Leslie, E. (2017). Fire and Water: Climate Change Adaptation in Harrop-Procter Community Forest. In Growing community forests: practice, research, and advocacy in Canada (pp. 180–185). Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ Gale, R., & Gale, F. (2006). Accounting for social impacts and costs in the forest industry, British Columbia. Environmental Impact Assessment Review,26(2), 139-155. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2005.02.002

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 British Columbia, Forest Practices Board. (2008). Audit of Forest Planning and Practices in the Kootenay Lake Forest District. Victoria, BC: Forest Practices Board.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 British Columbia Community Forest Association (2017). BC Community Forest Association Celebrates 15-Year Anniversary. Retrieved from http://bccfa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/BCCFA-Press-Release-June-18-2017.pdf

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Harrop-Procter Forest Products. (2015). Community Forest News. Retrieved November 18, 2018, from http://www.hpcommunityforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Community-Forest-Fall-Newsletter-2015.pdf

- ↑ Harrop-Procter Forest Products. (2015). Community Forest News. Retrieved November 18, 2018, http://hpcommunityforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Community-Forest-Spring-Newsletter-20151.pdf

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Greens of British Columbia. (n.d). Ramona Faust. Retrieved from https://www.bcgreens.ca/ramona_faust

- ↑ Bullock, R., & Hanna, K. (2012). A “watershed” case for community forestry in British Columbia's interior: The Creston Valley Forest Corporation. In Community Forestry: Local Values, Conflict and Forest Governance (pp. 82-99). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511978678.005

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Leslie, E. (2018). Climate change adaptation in our community forest. Harrop-Procter Forest Products . Retrieved from http://hpcommunityforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Erik-public-presentation-June2018.pdf

- ↑ Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. (2010). Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97(3), 147-155. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.05.006

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Ferrini, F., Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. C., & Fini, A. (2017). Routledge handbook of urban forestry. London: Routledge.

| This conservation resource was created by Dionne Wong. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |