Course:FRST370/Projects/Community forestry in Nepal's Terai region: assessing managerial and organizational operations

Community forestry in Nepal's Terai Region: assessing managerial and organizational operations

Community Forestry (CF) is a successful program implemented in Nepal, especially in hill regions. Its innovative decentralization policies, which call for active participation of local community do make sense in solving many problems, such as redistributing forestry resources fairly as well as protecting the forest conditions. However, these policies and measures are relatively new in Terai region, compared with those implemented in hill or high mountain regions. And its special location and community stakeholders even make the management difficult, which bring many challenges to nowadays Terai's CF. Thus this essay would firstly introduce the background of Terai region's CF, including it's history, stakeholders, policies and projects as well as different roles and rights. Then concentrating on the outcomes of nowadays Terai forestry's managerial and organizational operations, a discussion about the benefits and drawbacks of these methods would be mentioned and compared. The summary of the assessment results and a vision of the future would be included as conclusions.

Introduction

Geographic Information

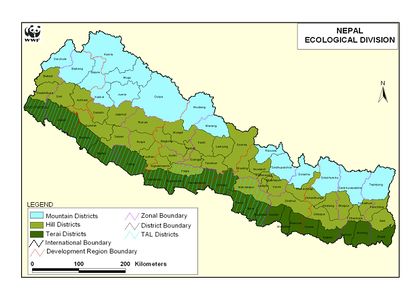

Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world with dominated agricultural economy (Malla, 2001). There have three main agro-ecological regions in Nepal, the Tarai, the Hills, and the High Mountains (Malla, 2001), and they are all bar-shape lands occupy the south, central and north of the country with similar acreage. Terai is on the southernmost part of Nepal, covering nearly 14 percent of the total Nepal's land area (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). The altitude of Terai ranges from 60 to 300 meters above sea level and most of the types of area is plain (Malla, 2001). Rice is the main crop and evergreen hardwood is predominant woody vegetation (Malla, 2001). The forestlands in Terai are of high economic value (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012).

Modern History of Forestry and Its Development

Nepal's history of forestry development could be divided into 4 phases (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). Prior to 1957, the whole Nepal, including the Terai region, were under the control of feudal system and forests were mainly controlled by local elites (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). The introduction of The Nationalization Act of 1957 (Nagendra, 2002) and the establishment of the system of political parities make all the country's forests were nationalized and controlled by the Forest Department (Malla, 2001). Thus from 1957 to the mid-1970s, nearly all the forests in Nepal, including those in Terai, are under the governance of the forestry department of the government (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). From the mid-1970s to 1993, the forestry policy became more and more open and decentralized. The National Forest Act of 1976 identified the indigenous people "is the important strength in forestry protection" (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012, para.10) and accorded them (usually the village committee) some power and obligation to manage a specific distributed forestland (Malla, 2001). National parks and forest reserves were then built and the government created a separate Department of Wildlife and National Parks to manage them (Malla, 2001). In 1993, the introduction of the Community Forestry Act "handed over all accessible forests to user groups" (Nagendra, 2002, para.3), which are the special groups mainly consist of the local people. Since then, the state government publicize many laws and regulations to specify the rights and advocate "co-management" (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). Therefore, from 1990 to the present, the Terai's forests are governed as "Community Forestry", which are operated under a multi-party system of policies with several civil social organizations (NGOs) (Malla, 2001).

The Change of Rights and tenures

Prior to 1957, most of the forests in Nepal, including those in Terai, were refered to as public resources (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). They were used and managed by the local people who lived inside or around the forests (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012), and there were only customary rights on this governance process. The rest of the forests are acted as private property owned by social elites like the generals (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012), where others cannot get in without the permits of the owner. User groups rights: provide them the right to manage and protect the forests, and the right to all forest produce and income derived from these forests. After the introduction of The Nationalization Act in 1957, all the forests in Nepal, including those in Terai were nationalized and managed by the government (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). This policy deprived the indigenous people of withdrawal rights and management rights, which were transferred to the government (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). They could not use and manage the forest resources as before, and their customary rights were not acknowledged. This evokes the conflict between the peoples and the government (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). Because of the few guards sent by the government (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012) and the neglect of the policy by some indigenous people (Malla, 2001), the legal rights were gradually useless and the natural forestlands were destroyed severely from 1957 to the mid-1970s. The National Forest Act of 1976 returned the use and management rights to the people (Nagendra, 2002), which highlight the continual uses and management of the forest by the villagers are the useful process to guarantee the normal and effective manufacture of the forest products (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). The power of the forestry department was gradually decentralized (Nagendra, 2002). Many forestlands, which were used to be the state property, now changed into communal property. Many rights such as exclusion rights, alienation rights and duration rights were transferred to District Forestry Department or even the village committees (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). However, there still existed public forests governed by District Forestry Department (Baral, & Subedi, 2017) and the state government still held the eminent domain of nearly all the forests (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). Then the Community Forestry Act in 1993 and some laws of forestry management transfer most of the rights of public forests to the user groups, which were consist of the local people (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). The user groups had nearly all the rights of the local forest especially the management rights and alienation rights, and the local forestry officers had "hand-over" rights of the forestry management as well as the supervision right (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). However, the Terai region seems to have a slower pace in carrying out these policies. And the effects of Community Forestry in this area seems to be immature and less successful than the regions of Hills and High Mountains (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004).

The Recent Forestry in Terai

In nowadays Terai, the forests could be divided into three types, the public forest, the communal forest and the private forest, among which the communal forest occupies the largest area (Baral, & Subedi, 2017). The Community Forestry program in Terai in recent years only practice in communal forest (Baral, & Subedi, 2017), which is advanced but complex (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012).

Terai's “Community Forestry” and CFUGs

In Terai, CF refers to "swathes of national forest where tenure rights are given to local communities, called Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs), for its development, conservation, and management to meet their local needs in a sustainable manner" (Birendra, Mohammod, & Inoue, 2014, para.7). Thus the CFUGs have many rights including withdrawal rights, management rights and alienation rights, and the state government owned the eminent domain. And the daily participation of the members in user groups include "decisions making, labour work and benefit sharing" (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004, para.13). Each member has "equal legal rights over forest resources through access to decision-making and benefit sharing" (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018, para.5), and co-operate to achieve collective benefits (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018). CFUGs have created forestry sources including sale of timber, firewood, and fodder or grasses and non-forestry sources which are mostly the fees (registration fee, membership fee, penalty fee) and collected a community fund from government and NGOs (Dhakal, & Masuda, 2009).

Affected Stakeholders

There are many affected stakeholders in Terai, most of whom are the locals. They are always the people living by the forest resources, being subject to the effects of the activities in the local forest area and participating in the governance directly .

| Stakeholders | Main Relevant Objectives | Relative Power and Interest |

|---|---|---|

| CFUGs | Manage the local forests' resources' gain and distribution, conservation, and protect members' rights | high power and high interest |

| Ordinary Peasants and Marginalised Immigrants | Asking for the fair rights of access, withdraw and participation | low power and high interest |

| Concession Owners | Negotiate in order to gain more profits | low power and high interest |

Interested Outside Stakeholders

There are also many interested stakeholders in Terai outside the forests. They are always the groups having the interest in the activities in Terai's forest area, and they usually interfere with the policy or project making processes.

| Stakeholders | Main Relevant Objectives | Relative Power and Interest |

|---|---|---|

| “FECOFUN” | Protect the develop local community forest | high power and high interest |

| Department of Forestry (DoF) | Restore deforestation, make more profits and prevent the withdraw by the locals from the nearby private forests | high power and high interest |

| Other NGOs | Negotiate to gain more profits or make sure the funds have helped the marginalized | low power and high interest |

"REDD+"

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, forest conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of carbon stocks (REDD+) is "the performance based policy intervention agreed under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)" (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018, para.2). This international climate policy is now used in Terai, seeking to reduce carbon emissions from Terai's forests by providing financial incentives (Khatri, 2018). It is a strategy to advocate and support sustainable forest management (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018) and to "mitigate forest-based contributions to climate change" (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018, para.2), including "deforestation and the fuelwood crisis" (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018, para.3). Nepal is now piloting REDD+ projects through community forestry (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018).

Assessment

After over two decades development of the Community Forestry program in Terai, this forestry management nowadays brings Terai both benefits and drawbacks. Below I evaluate and compare the results of managerial and organizational operations in Terai, pointing out some pros and cons (just discuss the management in communal forest because it’s where the Community Forestry program mostly carries on).

Advantages and benefits

(1) The introductions of decentralized and democratic laws and plans: Since the state government passed the new Forest Act in 1993, which is "more in line with the democratic principles, with control and authority for community forest management vested in the local community" (Malla, 2001, p.13), more and more detailed local plans and laws were then carried out. Both economic growth and environmental conservation are highlighted in these laws and plans (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018), with more and more concentration on the participation of the marginalized groups (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004).

(2) The active leading and participation of non-government organizations, acting as interested stakeholders: Some field projects have “co-operated with some of the most dynamic NGOS, taking advantage of their knowledge of community problems and needs, to promote community forestry as a means to rural development for the poorest peasant farmers” (Malla, 2001, p.15). Some other international organizations, such as WWF, APFNet, UNDP has raised amount of funds to provide many assistance items in Terai's Community Forestry (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). And "an alliance among field projects, NGOS, and FECOFUN executives has developed to put pressure on the government and especially the Forest Department", which may result in more suitable and democratic management and supervision without political monopoly or corruption (Malla, 2001, p.15).

(3) The increasing awareness of the sustainable development: Birendra (2014) found that CF system's outcomes "were found to be good in terms of forest protection” (Birendra, Mohammod, & Inoue, 2014, p.10). Many of the stakeholders "have mentioned the forest's environmental benefits as vital to them" and they "were willing to participate in protection activities" (Birendra, Mohammod, & Inoue, 2014, p.10). And Community members "developed positive attitudes toward the management process" (Birendra, Mohammod, & Inoue, 2014, p.10). The FECOFUN in recent years also spares no effort to help increasing the independent awareness and the abilities of operation and decision-making of the forest users in Terai (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012). The increasing enthusiasm, identity and awareness among stakeholders would definitely speed up the regulation plans and conservation process in Terai.

(4) Some advanced projects undergo in Terai: Terai has forests with high economic value (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012), which has been "strategically identified as the region with the highest economic potential" (Birendra, Mohammod, & Inoue, 2014), thus the state government is inviting many advanced projects so as to make the Community Forestry in Terai more effective and international (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018). For example, the REDD+ pilot project in Terai takes care of those marginalized people's participation, enabling them the equal rights to argue in the decision-making process, especially in making "benefit-sharing process" (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018).

Drawbacks and challenges

(1) Lack of transparency (Baral, & Subedi, 2017): Though CFUG and FECOFUN's original objectives are democratic and fair, the reality of distribution and participation of those marginalized is not quite as expected. Baral (2017) reported a fact that the elite members in social group tend to occupy all positions of the executive committee in Terai's Forest Community. Thus the other ordinary or marginalized members of the group do not know clearly the overall process, and some detailed vital decisions like the financial matters of the local Community Forest (Dhakal, & Masuda, 2009). These kind of monopoly also make the ordinary villagers unaware of the use of funds, and they have no choice but to receive the distribution of the communal income (Baral, & Subedi, 2017).

(2) Increasing conflicts among stakeholders: As has discussed above, there have many stakeholders in Terai's Community Forestry. Because they pursue different goals, they have different objectives and needs. The introduction of the Community Forestry Act in 1993 transfer the major governance power form the government to people (Zhuang, & Ke, & Long, 2012), it doesn’t benefit the majority of the ordinary people a lot. Because of non-transparency of the decision-making in executive committee (Baral, & Subedi, 2017) and interference of some other organizations (Malla, 2001), the peasant farmers have little strength to influence or even join in the decision-making processes but they should obey and follow the plans which do not represent their wiliness (Malla, 2001). Just as the embarrassing fact in West Bengal's forestry in India, where those peasants who just want some leaves and fuelwoods for living but were dispossessed because of the social group's willing to wait for those trees growing up to timbers (Menzies, 2007), Terai's village also has similar situation. These marginalized forest users had no way but to depend on the patronage of local elites for the forest products they needed (Malla, 2001), which would also mostly sacrifice their benefits or rights (Devkota, & Mustalahti, 2018). Thus those peasant farmers could hardly fully benefit from the new policies and projects to meet their own economic and political goals (Malla, 2001). And the conflicts among stakeholders are cumulating and increasing (Baral, & Subedi, 2017).

(3) "'Land grab' issue" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.1): "At many places, the House holds (HHs) situated near rich forests have shown a tendency to claim a large tract of forests, not even thinking properly whether they can actually manage such areas” (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.1). Some CFUG or the FECOFUN distribute the rights and responsibility so equally that they neglect the reality and peasants' wiliness (Baral, & Subedi, 2017).

(4) "Shift of pressure to public forests" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.3): Based on the Baral's (2017) finding in Terai's Churia forest, the local community would spare no effort to protect 'their' community forest when any forest area is handed over to them. "The elite members of the user committee put a ban against the use of forest products" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.3). Because of the shortage of daily use, including fuelwood, grazing and fodder, "the local users started harvesting the state forest with such an intensity that it culminated the exchange of firing between the District Forest Office and the local citizen" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.3). As a result, "carrying away green wood, poles and other forestry products from government forests is a common sight everywhere, and subsequently the state forest is depleting elsewhere" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.3).

(5) The immigration pressure: Nowadays most of the inhabitants are immigrants in Terai, including those from Middle hills or India, and the immigrants' number is increasing (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004). This fact has resulted in “considerable pressure on the forests and tension and conflict among the many different groups and individuals who rely upon these forests for their livelihoods” (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004, p.3). Most of the immigrants are the landless (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004), who received little education and knew little about Terai's forestry (Malla, 2001). However, they seem to "have received a disproportionate share of the benefits or played a dominating role in the CFUG decision-making processes" (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004, p.3), which would result in poor decisions and conflicts within the CFUG. The immigration pressure may also cause "forest encroachment" in Terai's forestlands (Paudel, & Pokharel, 2017).

Conclusions

The Community Forestry program has been practiced in Terai for more than 20 years (Gauli, & Rishi, 2004), which is an edge-cutting forestry governance projects around the world. Acted as a decentralized and democratic item, this program, along with some relevant policies and non-government organizations do benefit Terai a lot, such as the increasing participation of the marginalized and the rise of sustainable development awareness. However, there still exists many drawbacks for the governments like "lack of transparency" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017), "'land grab' issue" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.1) and "shift of pressure to public forests" (Baral, & Subedi, 2017, p.3), which result in increasing conflicts within and among stakeholders. Therefore social groups and the governments need to inspect and reconsider recent years' policies and projects so the rights of more marginalized groups would be guaranteed. Further analysis and exploring managerial methods should be applied and reviewed in Terai in order to make the Community Forestry program better.

Recommendations

This section is recommendations on the Terai's forestry situation from my personal perspectives. The Community Forestry program has succeeded in other regions in Nepal. That is to say, the policy and projects of this program is not the stumbling block of Terai's forestry. I think the main problem is the processes. In the decision-making processes, there are a number of marginalised people who cannot participate in, and the elites' monopoly this processes neglecting the wiliness of the ordinary stakeholders. In the distribution processes, those marginalised people are also neglected sometimes and some corruptions have been found in the use of funds. Thus the government should not only interfere with the CFUGs' activities, introducing more policies to guarantee the marginalised people's rights, but to distribute the internal power or set up a special department of internal supervision so as to prevent corruption. Moreover, some educational lectures about the Community Forestry program should be publicized in Terai's village in order to make people acknowledge their rights and the importance of the forestry conservation.

References

Baral, J. C., & Subedi, B. R. (2017). Is Community Forestry of Nepal's Terai in right direction? Banko Janakari, 9(2), 20. doi:10.3126/banko.v9i2.17661

Birendra, K., Mohammod, A. J., & Inoue, M. (2014). Community Forestry in Nepal’s Terai region: Local resource dependency and perception on institutional attributes. Environment and Natural Resources Research, 4(4) doi:10.5539/enrr.v4n4p142

Devkota, B., & Mustalahti, I. (2018). Complexities in accessing REDD plus benefits in Community Forestry: Evidence from Nepal's Terai region. International Forestry Review, 20(3), 332-345.

Dhakal, M., & Masuda, M. (2009). Generation and utilization of community fund in small-scale Community Forest management in the Terai region of Nepal. Banko Janakari, 17(2). doi:10.3126/banko.v17i2.2156

Gauli, K., & Rishi, P. (2004). Do the marginalised class really participate in Community Forestry? A case study from western Terai region of Nepal. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 14(2-4), 137-147. doi:10.1080/14728028.2004.9752488

Khatri, D. B., Marquardt, K., Pain, A., & Ojha, H. (2018). Shifting regimes of management and uses of forests: What might REDD+ implementation mean for Community Forestry? evidence from Nepal. Forest Policy and Economics, 92, 1-10. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2018.03.005

Malla, Y. B. (2001). Changing policies and the persistence of patron-client relations in Nepal: Stakeholders' responses to changes in forest policies. Environmental History, 6(2), 287-307. doi:10.2307/3985088

Menzies, N. K. (2007). Chapter 5: Kangra Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Our forest, your ecosystem, their timber: Communities, conservation, and the state in community-based forest management, 69-86. New York: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/menz13692

Nagendra, H. (2002). Tenure and forest conditions: Community Forestry in the Nepal Terai. Environmental Conservation, 29(4), 530-539. doi:10.1017/S037689 2902000383

Paudel, S. K., & Pokharel, B. K. (2017). Looking at the prospects of Community Forestry in the Terai region of Nepal. Banko Janakari, 11(2), 27. doi:10.3126/banko.v11i2.17244

Zhuang Z. F., & Ke S. F., & Long C. (2012). Development History, Organization Operation and Experiences of the Community Forestry in Nepal. Forestry Economics, 10(6), 123-128. doi:10.13843/j.cnki.lyjj.2012.10.028

| This conservation resource was created by Dongwu Zhan. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |