Course:FRST370/Projects/Community Forestry, Corruption, and Attempts for Conservation in Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam

Introduction

Tam Dao National Park (TDNP) exists within the Tam Dao mountain range of Northern Vietnam, 70 km from Hanoi; Vietnam's capital city. The national park contains a state protected and enforced “special use” forest, decided upon Vietnam’s Law on Forest Protection and Development; reserved for natural forest regeneration and protection.[3] The park was formed in 1996 which ranges 34,995 ha² across three provinces; Vinh Phuc, Thai Nguyen, and Tuyen Quang.[4] It is 100-1580 meters above sea level, and it has a tropical monsoonal climate.[2] The rainy season stretches from the months of April to October, making up 90 percent of the total annual rainfall received in the region.[2] November to March are dry and susceptible to wild fires[2]. TDNP is also a very bio-diverse region with 8 different forest types.[5] Surrounding the "special use" forest, there is a "buffer zone", where 27 communes of mostly forest dependent people exist.[5] The communes consist of the ethnic minorities of Vietnam.[5] The park attracts many tourists due to its mild climate, unique landscapes, and its close vicinity to the capital city.[5] It is one of the last primary forests to exist in Vietnam, while containing the countries richest levels of biodiversity.[2] However state enforced laws surrounding prohibition of extracting forest products and agricultural expansion from protected areas, threaten the biodiversity and can cause land degradation in areas of primary forest within the national park.[2]Tam Dao National Park is separated into zones, all with different forest management strategies employed by the governing state of Vietnam.[6] The core zone is "special use" natural forest; off limits from any resource extraction.[6] The buffer zone borders the core zone, and the national park office building and its staff are based in the administration zone.[6]

Main Stakeholders

Affected Stakeholders

Communes of the Buffer Zone in Tam Dao National Park

The affected stakeholder communities live within 27 different communes across a “buffer zone” that surrounds the border of the protected “special use” forest of the national park.[6] The boundaries of the buffer zone is demarcated by the state as a way to manage land use of the population of 193,000 inhabitants.[6][5] The buffer zone population had grown by 1.7 percent every year from 2001 to 2005.[5] 8 different ethnic minorities exist within the communes of the Buffer zone, including the Kinh (63% of population), San Diu (25% of population), San Chi, Dao, Tay, Nung, Cao Lan and Hoa (which make up 12% of the population).[5]

In 1997 the Buffer zone was placed into the national park boundaries, despite the park being protected as a “special-use” forest, where most human use is prohibited.[6] Much of the communities consist of ethnic minorities and are impoverished.[4] The village communes use forest resources to support their livelihoods through agro-forestry and tree plantations intended for industry use.[4] Some resources that the population is dependent on can involve land clearing.[4] This includes cultivation of rice and maize, medicine, housing materials, livestock grazing areas, and different cultural and spiritual practices[4]. Swidden agriculture is a method often used by commune farmers.[4]

The Institute of Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), is an interested Japanese state sanctioned research institute that surveyed two communes in 1998; Nin Lai and the Thien Ke communes in Son Duong District.[6] These communes may reflect the socio-economic makeup of some of the buffer zone inhabitants.[6]

Nin Lai Commune

The three ethnic groups included within this commune include the San Dieu (4,409 pop.); Kinh (1,913 pop.); and Dao (130 pop.).[6] The 6,542 commune inhabitants live within an area made up of 74% forest land, with 12% used as a plantation and 25% is natural un-touched forest.[6] Almost half of this commune resides within the boundaries of the National Park.[6] Based on 1997 Vietnamese figures, 15% of the commune was designated as being rich, where as 60% of the commune was designated as equally being both poor and average.[6]

Thien Ke commune

Seven Ethnic groups existed within this commune in 1998, including the San Dieu, Kinh; Dao; Hoa; Tay with a population of 5,274 people.[6] 80% of the land is forested, with agricultural activity making up 19%.[6] Only 3.5% of the forest is used for plantations, with 74% of the land being natural forest.[6] Vietnamese statistics designated that 20% of the commune was rich, yet 65% were average and 15% poor.[6]

Local Power Structures

There are commune level governments spread out between the 3 provinces of the buffer zone.[3] These local authorities are in charge of managing the “production forest,” which occurs outside of national park boundaries.[3] The local governments were in charge of disturbing the “Red Book” policy contracts, which was a state recognized tenure contract for agro-forestry production, beginning in 1993[3]. It was a contract that lasted 50 years, and it was renewable. The local governments are not capable of facilitating management decisions or enforce tenure rights with land claims in the national park.[3] However, they have been known to also recognize claim inside the national park boundaries against state laws, meaning they will not enforce restrictions upon park forest use as it falls out of their jurisdiction of power, and their goal is to support the livelihood of the local population.[3] National park land tenure is enforced and managed by the states park management board; a separate entity.[3] The communes are high interest, as their livelihood depends on the livelihoods of village inhabitants who also use forest resources, however they have no power to work with when asserting land claims or forest management decisions inside the national park.[3]

Interested Stakeholders

The National Park Management Board is a state sanctioned institution, over seen by Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), set to manage the park and protect its level of biodiversity by restricting land degradation, resource extraction, and agricultural expansion into the "special use" forest.[4] As of 2013, 100 people work in the headquarters, with 17 forest management stations dispersed around the park. They enforce tenure rights through conducting patrols; discussing with buffer zone villagers to stop using forest resources; providing oversight over tourism developments; biodiversity research; and educating the local people.[5] The State Forest Enterprises (SFEs) and park management board are both low interest stakeholders who hold high power when it comes to land claims and forest management decisions within TDNP, as the state at least can re-claim land from contract holders at any time. They are low interest because SFE employees simply are not recognized as commune members, nor do they anecdotally feel a part of their community. They moved to areas surrounding Tam Dao National Park for business ventures, not because they needed too for survival as some of the ethnic minorities in communes have shown. They occupy high power however, as SFE households are more likely to possess a forest protection contract, giving them full ownership over their tenure in terms with the contract signed with the state management board. Similarly park officials do not reside within the buffer zones, and gain an income separate from buffer zone agricultural production or collection of forest products.

The German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ) and The Institute of Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) are two international state organizations seeking to develop conservation solutions based within the park and buffer zone.[5][6] These two foreign state organizations have low interest, as they do not permanently live within the buffer zone, nor is their income dependent on forest products. They express high power however, as many positive reactions have resulted from bottom up and co-management conservation plans have been implemented. The investors of the tourist expansion named “Tam Dao two” is of an American company.[5] This foreign development is interested with high power, as their 300-million-dollar project has enticed national governments with economic revenue, and has already been constructed on such grounds.[5] However, they are low interest, as this development is not dependent on the survival of the investors livelihoods, and they may choose to not develop without the same level of consequence as a village commune member, who survives of forest products through food production or sale. The domestic NGO named Vietnam Environmental Center, is also a low interest high power stakeholder, as they are not directly affected by changes in the Tam Dao National Park management scheme. Instead they employ staff to develop school work on behalf of the conservation of the park itself, which takes power and influence to do such.

Tenure Arrangements

Pre-existing Tenure Rights

Commune level government were in charge of distributing forest tenure rights for land outside of national park territory, located in the buffer zone's “production forests."[3] This was done by handing down legal tenure ownership rights, recognized by the state, with the “Red Book” renewable contracts.[3] The Red Book policy allowed village households to gain forest use rights for 50 years, which started in 1993.[3] The land was allocated for forest timber production, where trees were to be planted, and eventually harvested for the economic benefit of the land holder (contract signee).[3] De facto access to forest land is also recognized by the local governments and thus it can be said to act as customary tenure ownership.[3] Customary tenure ownership in this case is defined by the fact local governments recognize the unwritten ownership of land tenure, which the state officials do not legally.[3] De facto forest land has been sold off to local officials by village customary tenure holders (for road construction), without title from the state recognized Red Book policy.[3] The State Park Management Board will not dispute de facto claims to land outside of the park, however, inside the park it is illegal to use “special use” forests without a state sanctioned forest protection contract.[3] Opposite from the state, the commune governments do not manage land within the national park, and they do not oppose de facto land use in national park territory.[3]

State Allocated Forest Protection Contracts

Forest Protection contracts included the devolving of state power in protection of forest resources within national park boundaries, through subsidized contracts in an area where the forest park management board has sovereignty.[3]This contract is an act to prevent further forest loss caused by agricultural expansion, through providing an alternative source of income and community forest based management.[3] Fire wood collection is not allowed, however in some regions, depending on the forest officer, the collection of deadwood is permissible.[3] Despite this resource extraction, everything else is strictly prohibited by state laws and enforced by park officials.[3]

History of Tenure Arrangements

During the 1940s, the northern region of Vietnam that is referred to as Tonkin, was under French colonial rule which had neglected its population into famine and poverty.[7] In 1945, the leader of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), Ho Chi Minh, was attempting to reduce land taxes and create land reforms in order to help with crop failures, Japanese takeover of rice, and Chinese authority over the rice trade.[7] Only 3.3% of the population in northern Vietnam had access to 24.5% of arable land, and Vietnam's peasant population that made up 58.9%, had authority over 11.1% of the arable land. Land reform was needed in order to help Vietnam's population fight against the hunger that took 2 million lives during this time.[7] From 1953-1956, the party had captured over two million hectares of land in Northern Vietnam from a “landlord class”, and was given for over two million smaller rural households.[7]

In 1954, the state created New Economic Zones in the mountainous highland regions of northern Vietnam, and obtaining land tenure was done legally.[7] Over 1 million people migrated into the low populated highland regions.[7] This was dubbed by the state as “rule by mobilization,” and the economic incentive of owning private land for agricultural activity motivated many households to seek out this territory.[7] More legislation followed by the state done in order to settle down nomadic swidden agriculturists who were also ethnic minorities, in attempts to monitor, prevent land disputes, and reduce forest loss caused by their roaming farming techniques.[7] This was called the "Fixed Cultivation and Permanent Settlement Program".[7]

Beginning in the 1950’s, Vietnam created Sate Forest Enterprises (SFEs) whom also moved into the highland regions next to local communities.[7] The population SFEs grew to 412, with obtaining control of 40% of Vietnam's forested land as of 2005.[7] The SFE was given governance over land that had a slope over 25 degrees, which meant highland forested areas easily fell to them.[7] SFE workers of these areas were not considered to be a part of commune communities, however some have been known to use forest resources for wage income.[7]

In 1972, the state General office of Forestry managed the protected areas of forested land, granting themselves control over deciding which forests could be used by SFEs, and what was to be preserved.[7] Management rights were also given to the SFEs of protected areas to manage.[7] The New Economic Zone inhabitants, and the Permanent Settlement Program Settlers (swidden farmers), both began to increase their activities, through burning more land to create more space for farming.[7] Swidden farmers were always known to burn down forest land for agricultural activity, so they took the blame from the state. This caused the SFEs protected land to lose a total of five million hectares, caused by SFE mismanagement, due to misdirection of funds to timber production and not conservation.[7]

This expansion caused problems and agricultural collectivization failed at the start of the 1980’s, and in some highland areas, 80% of the populations were experiencing hunger.[7] This hunger pushed farmers to expand more and more into the forested mountain regions to feed themselves, and as a consequence, forest cover depleted by 18% in Vietnam from 1976-1990.[7] In 1981 Directive 100 was legislated to fix these issues, by granting households specific areas of tenure for rice farming, and they were to sell at their quota while keeping anything above what they were required to market.[7] In 1993 a Land Law was passed by the state, which meant that allocated land tenure could be long-term through a registered certificate process (Red Book), which can be sold, traded, mortgaged, and inherited under the discretion of the land owner.[7] These contracts were handed out by the local governments.[7] While Local governments can give out land law contracts to households, the state can always take their land under this contract at any time if there is misuse or any public welfare concerns.[7]

In 1992, Program 327 was instituted by the state, which was the forest land allocation program, done as a movement to reforest the mountains.[7] Every household was to be given tenure, and must reforest and manage it from destruction, with government help to cover planting costs.[7] Green books were divvied out which contained the location of their tenure land, responsibilities, and rights specified about harvesting mature trees on behalf of the household.[7] 500,000 households received contracts between 1993-1997.[7] Special use forests as in national park territory could also be given out in a contract to households for protection, in a way to provide funds to support livelihoods, while giving households forest management responsibilities.[7]

In conclusion two Contracts existed in the 1990s; agro forestry production of forest land, and “special use” forests protection contracts.[7] Commune boards were to hand them both out, as any household was qualified at a contract of forest use rights, through a democratic process by three meetings that were to teach about the contracts and decide where to allocate land for each household applicant.[7]

Unfortunately, according to researcher Cari An Coe, currently only 168 households out of 42,000 received forest protection contracts of land specifically in Tam Dao National Park.[4] This occurred during Decision 661, which was divided out now by the national park management board, and not commune level governments in 2001, as past land claims were taken away.[4] VND 3,350,000 is given for each contract holder, which on average means the doubling of income, while also being able to collect fallen wood. Unequal land allocation among commune members meant conflict and negative sentiment for those that currently hold contracts.[4] The state now has management discretion over the national park, and can decide who gets land tenure rights through what is supposed to be a open and fair process for all.[4]

Corrupted Actions of Tenure Arrangements

Affected local level governments and interested State Park Management Board members had pre-existing conflict over the recognition of tenure rights for villagers in the protected national park forests, causing the state officials to disobey equitable allocation of contracts, in attempts to restrict forest use within the national park.[3] The allocation of forest protection contracts has been noted to be have been a closed and exclusionary process, whereby elite members captured tenure arrangements from the rest of the general village population.[3] Research shows that the management board wrongly broke the intended purpose of said contracts of community based forestry and avoided working with local commune level governments; local governments that had supported swidden agriculture practices, and both de jure and de facto tenure rights that also occurred within the national park.[4] The fact that many of these claims to tenure occurred within the national park, was of concern to the state park management board as their main objective was to stop forest land use within its boundaries. Thus the board gave it to an elite population that do not depend on said forest resources, and they feared a “community capture” of resources that was thought to be best avoided to prevent further land degradation.[4]

Pre-existing land claims of the national park were also corrupted during its formation, as the national park management board tried to reorganize these land rights after 2000, under the new direction of Decision 661[4]. Paperwork was an issue for the state management board to file, and they decided that one household name could represent multiple to make this process easier to document. [4]However, under the new law of Decision 661, a park official stated that only households with adequate levels of labor force were motivated by the state to maintain their forest tenure rights through this contract because they were worried that the income paid by the state was not enough for multiple households.[4] If a household was deemed to not have an adequate labor force, then the name on the contract kept all of the allocated land to themselves as a way for the park management board to offer substantial economic benefits.[4]

Statistical tests done by a study published by the Journal of Forestry found that a significant portion of households who held greater levels of education (of one more year), or that had a employee(s) of a SFE, held contracts 10-20% more often then non-contract holders.[4] Household histories of practicing swidden agriculture, or that had either de jure or de facto access to forest land, were not chosen as often by the state management board when allocating forest protection contracts.[4]

Only 11 of the 41 households that had contracts said that they heard about the contracts through public announcements.[4] Thus 74% of the households admitted to being privately contacted about the contract from park officials.[4] 27 households (65%), had Forest Protection Officers visit them in proposing the contract.[4] Others claimed that their connections with SFE workers, or previous de jure land owners from program 327/661, had told them about the contract.[4] A household remarked that the reason he got invited by the protection officer was because he had a “golden face,” which translates to being a good person.[4] This remark helps back the claim that those with history of personal connections, education, employment status, or trust at managing land were chosen.[4] This was a clear bias introduced among a supposed diplomatic process of allocating land tenure.[4]

A Kinh village member was interviewed during a study in 2015, and after he was asked about the fairness behind tenure allocation through these forest protection contracts, he stated, “having to be ‘in the know’ in order to be able to get a contract is not fair.[4] Conversely, a forest protections officer that was employed by the state, told the researcher that most commune members did not initially seem enticed by the contracts and that they were rather “stunned like fish out of water."[4] A lot of village members also reported not knowing about these contracts to begin with. Out of a sample of 59 households, 42 had expressed to the researcher that the allocation process of contracts was imbalanced.[4]

Ecology of Tam Dao National Park

The TDNP has 1,282 plant species, 87 mammal species, 280 bird species, 180 reptile and amphibian species, and 360 different species of butterfly.[5][9] 42 plant species are endemic to the park itself, with 64 being classified as rare, requiring protection. 234 plant species are also economically valuable."[5] The TDNP can be distinguished into eight different forest types: “tropical evergreen forest; (2) sub-montane evergreen forest, on middle and upper slopes; (3) montane (elfin) forest, on the mountain tops; (4) bamboo forest; (5) regenerating forest, after slash and burn cultivation; (6) plantation forest; (7) grassland; and (8) shrubs and grassland."[5]

The Asian Black Bear and the Malayan Sun Bear are said to probably still exist within the national park, however with only a few.[10] Illegal hunting practices, done notoriously for bile medicine threatens their existence within park boundaries."[10] Coupled with habitat loss, they may become locally extinct from the park in the future. Similarly, the Golden Cat is threatened by illegal hunting and habitat loss.[10] A field survey observed a Golden cat in 2004, where it came down to a village to prey upon a domestic animals.[10] This observation proves how close the habitat of threatened species are with local human populations, and how serious the loss of primary forest is for the national parks biodiversity."[10]

Conservation Importance of National Park

Human Land Use and Biodiversity Conflict

After TDNP was declared, a survey done in 2005 had expressed that 30% of households were negatively effected through income, as forest resources became prohibited.[5] Because agricultural land is so sparse, it is claimed that half of the population, especially from the poor class, still depend on the forest to support their livelihoods.[5] Of the 87 mammal species, 19 of which are global conservation priorities, and 24 are considered to be endangered according to the Government of Vietnam.[5] 38 species of reptile and amphibian also make the IUCN Red List and the “Red Data Book of Vietnam."[5] Some species under these classifications are caught by locals for sale in the wildlife trade.[5] From 1999 to 2005, “rich” and “medium” bio-diverse hot spots had experienced a decline in size, from declination rates increasing from 10.2% to 13.4%.[7]

The wildlife trade has said to be increased in tourist hot spots such as Tam Dao Town, often perpetrated by domestic visitors stemming from Hanoi[5]. The state management of 'The Forest Investigation Sub-Station' in the buffer zone, has been proven ineffective at prohibiting all wildlife trade purchases.[5] Neither is there education about the impacts surrounding the wildlife trade is provided for tourists[5]. A U.S. invested American project, named “Tam Dao 2” also is a threat to the biodiversity of the park, as this USD 300 million dollar project is trying to secure 1.1% of national park land to construct hotels and golf courses for the leisure of outsiders. This interested stakeholder will not benefit the local affected population.[5] Similarly, on a Island of Zanzibar named Misali, a foreign tourist development meant constructing a resort on considered sacred grounds of a local Muslim population.[12] Fisherman would have been directly affected, as they may have not been allowed to dock or camp on the islands during storm or nightfall.[12] In both cases, foreign tourism developments can were being done despite impeding upon local resource collection.

A research study conducted in Tam Dao National Park, which addressed butterfly species diversity, evenness, richness within five different habitat types discovered troubling insight on the effects of habitat loss.[9] This study helps better understand the consequences of human disturbances.[13] From 2002-2004 they found that forest edges contained the highest diversity of butterfly species, while also having the highest recorded total population. Moderate disturbed forests fell in second.[9] However, natural closed forests (no disturbance) contains most of the rare butterfly species that are endemic to this region.[13] These species also are showing a decline in population after a disturbance is made; therefore, this proves forest management is needed to protect these habitats.[9] Lastly, agricultural land contains the least amount of diversity overall, proving that heavy disturbance can have a very direct impact on biodiversity.[9]

Future Trends of Forest Land Degradation

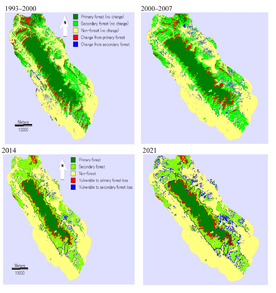

A scientific study from the journal of “Remote Sensing,” investigated the future trends of forest land degradation in order to provide forest managers with locations on areas that are in need of further protection.[2] The study used Landsat satellite imagery, from a temporal scale from 1993 to 2007.[2] The land classification included primary forest, secondary forest, rain-fed agriculture, paddy rice, settlement and water.[2] From 1993-2000, primary forest decreased 20.59%, however secondary forest, which is defined as selective logging in primary forests, experienced an increase in 9.51%.[2] From 2000-2007, 16.12 % of primary forest was lost, and only 0.88% of secondary forest increased, due to less selective logging.[2] Non-forested classes increased by 4,080 hectares (1993-2000) and 4,508 hectares (2000-2007).[2]

Based on the studies model, primary forest was said to decrease from 18.03 % in 2007 to 15.10% in 2014, and later 12.66% in 2021.[2] Secondary forests however will only decrease 1% from 2007 to 2021.[2] Further, the non-forested areas which could be as a result from agricultural expansion, is said to increase from 50.81% in 2007, to 54.01% in 2014, to 57.16% in 2021.[2] The land law from 1993 also may have caused an increase in non-forested areas once households were given tenure rights through the Red Book before state laws regulated land in what was to become national park territory.[2]

Reforestation and Conservation Initiatives

Initial reforestation initiatives began as early as 1940, from French colonial powers who used Pinus massoniana Lambert and Erythrophloeum fordii Oliver.[13] In 1962, SFE’s also mostly used Pinus massoniana in reforestation efforts, because of its toleration of low PH soils that have been strip bare of vegetation.[13] Fortunately these plantations still existed after the parks creation, allowing native species to recolonize in the under story.[13]

Three government and international donor-funded projects have sought out to reach a beneficial relationship between balancing village inhabitants livelihoods, in line with protecting the primary forest of the national park.[5] In 1998, the state issued Programme 661, publicly known as the “5 Million Hectares Re-forestation Programme, which sought to plant 3 million hectares to support agro-forestry plantations, and 2 million hectares be restricted from harvest as “special use.”[7] Programme 135 sought to support local impoverished communes by way of reforestation for harvest.[5] Lastly, Programme 133 sought to decrease poverty in the buffer zone.[5]

The German Technical Cooperation agency (GTZ) is a devoted interested group of the national park that has begun multiple programs, one of which for example is centered around educating tourists through a “forest school”, in attempt to ensure conservation of the parks habitats and levels of biodiversity.[5] For instance, walking trails had been created for safe viewing of birds. In 2003, the GTZ started a project centered around conservation of the parks forest resources, while improving the livelihoods of local villagers.[5] It was named “Tam Dao National Park and Buffer Zone management project,” and is striven to complete 4 goals; educate the current management rules of the park; introduce co-management; provide alternative income revenue; and education.[5] These programs have been said to be successful in bringing a healthy level of cooperation and dialogue between commune inhabitants and their respective local governments, with district, national and international stakeholders.[5] Relationships between park staff and villagers have been said to improve.[5] The states Forest Protection Department of Vietnam also received an adequate training program from GTZ that allowed park staff to improve their roles in working with inhabitants, while also ensuring the protection of the park itself.[5] Off farm jobs were also offered to villagers, thus allowing more trust and cooperation with conservationists of the park.[5]

A domestic NGO named Vietnam Environmental Center, aimed to develop an environmental curriculum for two communes in the primary and secondary school levels.[5] From 1997 to 2000, the United Nations provided a 'World Food Program' known locally as PAM, which gave buffer zone inhabitants tree seedlings and traded rice on the condition of starting agro-forestry production.[7] The mission of this project was trying to benefit the local communities livelihoods while also reforesting areas, and it directly followed up program 327's similar efforts.[7]

Challenges

Consequences of Corrupted Tenure Arrangements

A study conducted by Mekong Economics that took place in 2005 has been cited in a 2013 journal article that claims that half of the local livelihoods are solely maintained from collection of forest resources, usually from households experiencing low incomes.[5] The national park’s creation 1996 was done to restrict forest access, and disregard past de facto or current de jure rights, making logging and non timber forest products illegal, despite it offering a higher income than agricultural practice.[5] However, the 2005 study expressed that some households experienced a 30% drop in their annual income.[5] Through Programme 661, there is difficulty in actually supporting livelihoods of local peoples, despite rural road construction, and the implementation of forest protection contracts.[5] This is due to a lack of funds to manage the park in this program.[5]

Researcher Cari Coe, led a survey of households that weren’t given contracts expressed either that the allocation of tenure was unfair, or that they didn’t even know it existed since very few households even had them.[4] Forest protection as a result did not include community participation, and the large tracts of land given to few households meant that management was very difficulty and went unforced.[4] Levels of resentfulness was carried out by non-contract holders towards contract holders, and when managers were strict on protecting their land, they retaliated.[4] This caused a lax approach to management and enforcement out of fear.[4]

The ethnic minorities living in communes has been cited to express vacant information on the pluses of both forest conservation and biodiversity.[5] Education is lacking, and needed if the state wants to better convince commune inhabitants to carry out alternative income revenue than using forest products.[5] Programs facilitated by the GTZ can educate them on the offering of such alternatives, however this requires time and effort for protecting the bio diverse integrity of the park.[5] Based on assessments from the 2013 journal article published by the 'Center for International Research,' still state there is more education needed despite efforts made by both the state and foreign organizations, as land loss is expected to increase.[5][2]

Solutions and Recommendations

The Center for International Forestry Research stated in a journal article that education can act as a strong way forward for protecting the biodiversity and ecological integrity of primary forests, while seeking economical benefits for the buffer zone inhabitants[5]. The buffer zone inhabitants require more education to be instituted so that villagers can understand the importance of biodiversity and the adverse consequences of land degradation.[5] Education for tourists and proper training for forest rangers is also needed said to be needed despite focused attempts.[5] They also stated that the state management board needs to collaborate with the local governments to figure out plans to benefit profit from the tourism industry.[5]

The Forest Protection Department, has been stepping in and teaching buffer zone inhabitants about protecting biodiversity and values in conservation, on behalf of the national park.[5] The Mekong Economics group conducted a survey in 2005 investigating the impacts of the program, and unfortunately 50% of interviewed participants didn't know their village land limits in bordering the national park.[5] This causes further resource collection in restricted “special use” forests without the general population knowing they are committing illegal activities.[5] Thus further education is required.

Remote sensing technology also plays a large role in determining areas that are in need of protection, based on identifying forest land degradation trends as shown in the study article published by the journal of Remote Sensing.[2] Using land sat imagery, scientists were able to provide forest managers valuable insight in areas that are at stake of losing the most biodiversity, allowing for the prioritization of conservation efforts.[2] For example, it is said in the article that park regions that reach an elevation of 350 to 800 meters above sea level, promise the richest plant species structure, and that forest loss is believed to continue and threaten these areas.[2] Conversion of secondary forests into agricultural plots also increases the risk of soil erosion.[2] Following these results can help the state management board allocate their funds more wisely, as well to ensure a future for endangered species of the national park.[2]

Experienced Researcher of the Tam Dao's buffer zone stated democratic allocation of tenure is needed to ensure park protection.[4] Fair compensation will also further provide an incentive of protection by all village members who should equally carry similar contracts. Local governments must also work with state bodies, in order to reach agreements on the parks protection.[4] Unbalanced approaches to community forestry can have the opposite intended effect of protection, and it is wise to get all stakeholders to value the same principles, if devolving state forest management responsibilities is desired.[4]

References

- ↑ Khương, V.H. (2008). Tam Dao mountain range [photograph]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tam_Dao_mountain_range.jpg

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 Khoi & Murayama, D. D., Yuji (2010). "Forecasting Areas Vulnerable to Forest Conversion in the Tam Dao National Park Region, Vietnam". Remote Sensing: 1249–1272 – via Remote Sensing.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 Coe, Cari An (2012). "Local Power Structures and Their Effect on Forest Land Allocation in the Buffer Zone of Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam". Sage. 22: 75–101 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 Coe, Cari Ann (2015). "The allocation of household-based forest protection contracts in Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam: Elite capture as a bureaucratic impulse against community capture". Journal of Sustainable Forestry. 35: 90 – via Journal of Sustainable Forestry.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 5.40 5.41 5.42 5.43 5.44 5.45 5.46 5.47 5.48 5.49 Sunderland, Sayer, Hoang, Minh-ha (2013). "Evidence-based Conservation Lessons from the Lower Mekong". Center for International Forestry Research: 50–59 – via Center for International Forestry Research.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Tsuchiya,, Toshiyuki (1998). "Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam – forest utilization by forest dwellers". Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: 279–282 – via Institute for Global Environmental Strategies.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 7.27 7.28 7.29 7.30 7.31 7.32 7.33 7.34 7.35 Cari, Coe An (2008). A tragedy, but no commons: The failure of “community -based” forestry in the buffer zone of Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam, and the role of household property rights and bureaucratic conflict. University of California: ProQuest. pp. 82–263.

- ↑ Stout, K. (2010). Asian golden cat [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Asian_Golden_cat.jpg

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Vu, Lien Van (2008). "Diversity and similarity of butterfly communities in five different habitat types at Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam". Journal of Zoology. 277: 15–21 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "RAPID ASSESSMENT OF MAMMALS IN THE TAM DAO NATIONAL PARK". GTZ: 38–39. June 2005 – via CeREC Vietnam.

- ↑ Naniwadekar, R. (2006). Striped Ringlet Ragadia crisilda from Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Close_wing_position_of_Ragadia_crisilda_Hewitson,_1862_%E2%80%93_White-striped_Ringlet.jpg

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Menzies, Nicholas K. (2007). Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber Chapter 5. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 34.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Cuong, Lamb, and Hockings, Chu Van, David, Marc (2013). "Simple Plantations Have the Potential to Enhance Biodiversity in Degraded Areas of Tam Dao National Park, Vietnam". Natural Areas Journal. 33: 139–146 – via BioOne Research Evolved.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Lambert, A. (1832). Pinus massoniana [painting]. Retreived from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pinus_massoniana1.jpg

| This conservation resource was created by Ben Eisner. |