Course:FRST370/Impacts on forests and people of the palm oil industry in Kalimantan, Indonesia

The oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) was introduced by the Indonesia government at the year of 1979, as a response of national economic policy transformation of developing natural resources under a decentralization background.[1] The plantation of oil palm created opportunities for millions of smallholders in Indonesia and Malaysia.[2] Planting of oil palm became a trend from that moment. Kalimantan is the second large palm oil production region in Indonesia, accounts for 40% of the total national production. The economic benefits that accrue from oil palm plantations are huge but the price is also notable.

The local ecosystem is suffering irreversible damage due to deforestation and land conversion. [3]Endemic species and overall biodiversity are being lost at a very fast rate. Even the water supply is also influenced by land conversion. The changes in land use and land cover in Kalimantan increase greenhouse gas emissions. Around 40% of the lowland forest was lost from 1990 to 2005[4]. Approximately half of the land cover for oil palm was a forest. Plantations replaced many agroforests and agricultural land, and the soil type after conversion was mineral soil and peatlands. The development of oil palm plantations definitely caused deforestation and forest loss. It caused loss of forest cover of intact, secondary, and logged forest. Also, forest fire was one of the factors leading to land clearing.

Besides, the potential problems of decentralization have been shown recently. The complex and chaotic tenure and license systems of land ownership, rights and oil palm plantation lead to multiple conflicts between smallholders, community (indigenous) members, palm oil companies and the government. Most forests of Kalimantan are facing multiple claims from different stakeholders.

Description

Kalimantan is the Indonesian portion of the island of Borneo. It accounts for over 70% of the total of the island. Kalimantan and the central Borneo's flora is among the most diverse and plentiful to be found anywhere. Thousands of plants, many of them unique, are to be found in Borneo's forests. More than 3000 species of trees, of theses 155 are endemic to Borneo. [2]However, the planting of oil palms (either Elaeis guineensis, Elaeis oleifera and Attalea maripa.) which indicated success in economic terms lead to a trend of increasing oil palms plantations. Even former hunters/gatherers are planting oil palm seedlings as the way forward to economic prosperity. [2] From 1996 to 2003, the area planted to oil palm in Indonesia more than doubled from 2.2 to 5.2 million ha, while the production of crude palm oil increased from 4.9 to 9.8 million tons. The bright future of palm oil plantation also attracts many investors and companies get involved in this field, and the capital and resources from Indonesia and international companies industrialize the palm oil business.

The prosperity of the Kalimantan economy is compromised by the loss of natural tropical rainforest. Around 56% of protected lowland tropical rainforest in Kalimantan were cut down between 1985 and 2001 to supply global timber demand – more than 29,000 km2 (almost the size of Belgium).[3] After the clearcutting, the logging company did not reforest the land but sell the land to palm oil companies in return for revenue share. So that oil palm development is one of the biggest drivers of deforestation in Kalimantan. Malaysia and Indonesia account for 90% of the world's total oil palm production area, and the demand is still increasing. But, the truth is Kalimantan and entire Borneo is not suitable for oil palm production due to many reasons.[3] The land conversion has not only lead to huge damage to local ecosystems but also social and economic conflicts between local communities and logging, palm oil companies, sometimes even initiate some violent protest against the government. The sustainability of the palm oil industry and community members' well-being, as well as forest conservation, are three top dimensions in this study.

Tenure arrangements

Tenure arrangements. Describe the nature of the tenure: freehold or forest management agreement/arrangements, duration, etc.

In Kalimantan, many forest resources are owned by indigenous people for hundreds of years. Indigenous people rely on the forest for their own purposes in agricultural and timber production, which brings revenue by trading. However, the state has claimed the statutory rights. Indonesia has accepted the customary rights of indigenous people in the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35/2012. Oil palm is one of the most rapidly increasing crop and fast-developing industries, which has replaced many areas in Southeast Asia. The states start to give out permits to investors to develop palm companies in Indonesia, so the statutory rights have overlapped with the previous customary rights. The state has decentralized authority into communities, individuals and companies to manage the land together. Also, the companies hold over 50% of land tenure in Kalimantan. Many companies are allowed to build their own oil palm plantations, so the land, which used to belong to indigenous people are taken away, which causes tenure conflicts.

Customary rights

The customary land tenure can be determined into 3 types[5].

- Customary land is owned or controlled by a customary group.

- Customary land is owned by individuals.

- Customary rights owned by individuals or heirs.

The tenure right can be divided into 4 categories: private, communal, open access, and state. There are several national parks in Kalimantan that are open access and state owned. Private tenure rights can be the rights held by an individual or a family. Communal rights are the tenure rights held by several groups of indigenous people.

Most indigenous communities have marked their own territories based on different geographical features, by previous warfare or negotiations back in history. For those villages that are close to each other and use the same languages have formed ‘continuous villages’[6], so they share common land and tree tenure system. They usually take a turn to cultivate and harvest by using their local traditional knowledge. They are the customary group control and own the land. However, it may cause individualization of communal rights. It is one of the problems of the indigenous tenure system. It causes unlimited access by different groups. It causes tenure conflict and illegal encroachment of the land. In West Kalimantan, women can inherit the tenure rights from their parents. it is the example of customary rights owned by heirs.

Statutory rights

Local government converts those lands -- which lands? -- for large-scale development into productive use for sustainable land development and management. Indigenous people are allowed to participate in land-use decisions to form community-based management. The government issued a large number of Hak Pemungutan Hasil Hutan (HPHHP) permits to investors because of limited facilities and resources to encourage them to develop the oil palm industry in the district[7]. HPHH scheme led to the acceleration in deforestation and disagreements from different stakeholders, so the district government set a more equitable and sustainable forest regime. The government has divided the land into different uses in agriculture, timber production, and oil palm plantations, which has divided tenure rights to different groups of people.

Administrative arrangements

Administrative structure and decentralization

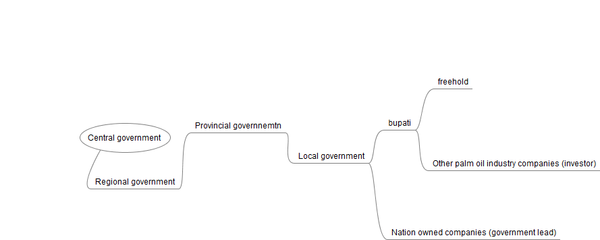

Indonesia is a decentralized democratic republic, in which district governments and municipalities provide most governmental services. However, the ultimate authority over the management of forests lies at the national level[7]. There are five provinces in Kalimantan, each of them has their own provincial government. According to the 1980s forest classification (Tata Guna Hutan Kesepakatan, tghk), agricultural activities, including estate crops such as oil palm, may take place only in areas of ‘conversion forest’.[2] This means the "conversion forest" classification is directly identified by a government official, and the government plays a major role in the land arrangement. Beginning in 1999 decentralization, the local government can set up bupatises as to manage local district natural resources, they can enact their own regulations which do not conflict with existing laws. The first generation of empowered bupatis was selected by members of the district parliament. The bupatis allocate the "conversion forest" and "protection forest" to different stakeholders within the area. A bupati could give licenses to whomever he wanted, without public consultation or bidding, which lead to a boom in plantation licenses.[8][1]

The complexity of government structure and stewardship

However, Indonesia's system of regional autonomy has caused a drastic proliferation of law-making bodies; more than 1,000 bodies and individuals currently have law-making powers under this complicated system of overlapping or contradictory authorities over forest resources at the provincial and district-levels of government. This number is likely to further increase as provinces, districts, and other tiers of government are carved out from existing regions.[7]

Corruption

In Indonesia, decentralization efforts are frequently compromised by weak administrative capacity, low funding support for resource management and service provision, poor political accountability, and the absence of a strong civil society needed to ensure local representation. As a consequence, decentralization reform often leads to local corruption, resource capture by local elites or the military, and the monopolization of governance roles by the elite class.[1]

Affected Stakeholders

An affected stakeholder is any person, group of people, or entities who live in the area is affected by the activities happens in the area.

The development of palm oil industries has been hastened in recent years. Many local people, groups, or companies are influenced, in losing land tenure rights, developing other industry chains, gaining labour or economic benefits. The table below shows the affected stakeholders and their related affected level and their power.

| Affected stakeholders | relevant objectives | relative power and affected level |

|---|---|---|

| Companies that own by local people | Have more economic trade | high power/ high level |

| smallholder farmers | Grow more crops to gain economic benefit | medium power / medium level |

| Dayak community | Land that they owned were taken away, their power is overlapped by other shareholders. However, they can have more working experience, which can promotes economic and facility of the land to the community. | lower power / very high level |

| Employees in oil palm companies | salaries and working chances | no power / medium level |

Companies that are owned by local people hold the land to develop oil palm industry, they are willing to the development; however, they are affected by the increasing number of outside investors, which forms competition in business.

Smallholder farms would like to get more benefits to grow more crops, but they can keep their land for certain purposes.

Dayak community is the group who loss their land, they agree and disagree in different content. They like to see the development of the community, however, once the companies are close, they are highly affected by this act. Although the nation has admitted their tenure rights, the tenure rights of groups who got forest license has a conflict with indigenous people.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

An interested stakeholder is usually standing for any person, group of people, or entities that have shown an interest, or is known to have an interest in the activities of a forest area.

palm oil industry attracts a huge amount of investors and companies, both national and international, for those companies are not made up by local communities and smallholders (not owing to a freehold or community license, or indigenous people with recognized communal title), but showing and performing an interest toward local resources should be listed as interested stakeholders.

| interested stakeholders | relevant objectives | relative power and interest level |

|---|---|---|

| Central government of Indonesia | National economic development, environmental conservation, enhance citizens' well-beings, etc. | Strongest power / lowest interest in local scale |

| Regional goverment of Indonesia | Regional economic development, environmental conservation, enhance residents' well-beings, etc. | Moderately strong power / relative low interest |

| Provincial government of Indonesia | Provincial economic development, environmental conservation, enhance residents' well-beings, etc. | Strong power / relative low interest |

| Bupati | Better license arrangement | Strong power in local design-making/ high interest |

| Companies and investors (not local) | Enhance revenue | Weak power, but has more capital resources / extreme high interest |

| Global consumers | Purchanse cheap palm oil | No power / low interest |

| NGOs | environment conservation, local communities' well-being | Relative weak power / medium interest level |

A notable finding is that companies and investors in Kalimantan are weak in political power but strong in capital power. A case of a company called PT Arjuna Utama Sawit (PT AUS) bribery to the local forestry officer and get the permission of land conversion is a good example of using capital as a trade of political power.[1]

This company was responsible for the destruction of 970 hectares of forest and as oil palm concession. And the ministry of forest in Indonesia was seeking compensation of 497.15 billion Indonesian Rupiah for forest recover. They also want PT AUS to plant trees from the burned and clearcutting area, also a fine for each palm tree planted will be given.[9]

Discussion

The major reason for the conflict is the lack of respect for local customary laws. Also, the rights of rural populations are often ignored during national regulations, when they are defining tenure rights.

Road development

The government builds roads in Kalimantan to promote the development of the economy, but it has negatively influenced the ecosystem. Ujioh Bilang was disconnected from outside because the heavy rain caused the river to overflow its banks. The necessaries of villagers in Ujioh Bilang have to delivered through road, which leads to the district’s road development plan. Oil palm plantations run neatly alongside the road, where was logged before, which benefit extractive industries, such as palm oil and mining, more than the locals. Palm oil firm expects the development of roads, which leads to the expansion of oil palm plantations. Companies use Mahakam River to transport palm fruit, but if the river level decreases, they will need to transport fruits by road. It has satisfied the needs of oil palm companies in transportation.[10]

Management Conflict

Oil palm has expanded and overlay some of the areas of community-managed land. Those converted areas will be controlled by oil palm plantation.[4]The oil palm companies (PT LonSum) in Kutai Barat was surrounded by conflict by Dayak Benuaq people because the company set plantation on land belongs to Dayak people. The cessation of planting by the company eased the tenure conflict, but many indigenous people lost their land and livelihoods. So it comes out new HPHH permits were under control by the Kutai Barat government in a transparent and slow procedure to balance the sustainable forest management and conflict between different stakeholders.[6]

Gender Conflict in the Community

There are 3 changes in gender patterns following the development of oil palm industries tenure rights, division of labours, and the sources of income. There is an example of the Dayak Hibun community in West Kalimantan. It has negatively eroded women’s rights to the land. The development of the palm oil industry brings a huge gap of wealth vs wealth to the community. Women have lost tenure rights, which they inherited from their parents. Land rights used to be the protection of rural women and their children. Once the land is signed under males in the family as the smallholder, women lost their tenure rights, so they cannot get formal credit sources. They spend more time in oil palm cultivation than men, where the lands were not belonging to them. Women are important in the progress of the social reproduction of the oil palm plantation because they are not highly educated, so what they can do is to use their traditional knowledge to work in plantations and become daily labour workforce. It led to the exclusion of many women from the organization.[11]

Assessment

The central government of Indonesia has the power to control and manage all the land resources except those land has been authorized to others. Then, it decentralizes its authority to provincial and district governments. The provincial/district governments should respond to international conventions related to forestry, flora-fauna protection and conservation, and climate change, since the national government has ratified these conventions, including the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Convention on Climate Change.[5] District/municipality governments are authorized to deliver mandates, including related to land use, development planning, environment, and land registry. Several optional mandates for local governments include agriculture, forestry, energy and mineral resource. [5] Local government can define land classifications and functions. Land Agency and the Ministry of Forestry, several other central government agencies have some power to claim lands, such as agencies handling mining and infrastructure.[5]

Conflicts always exist between indigenous people, who claim their customary rights, and government agencies, which always want to exert their power to control the land. Indigenous people are the response for their land conservation and protection. They can manage their forest resources for different purposes. Local communities can develop together with oil palm plantation, which also follows with risks. Employees in oil palm companies do not have power to change the decision. However, when the company was controlled by the government, many people lost working chances.

Recommendations

- Integrate different government department, standardize law and regulation within regions

- It is not easy to find any government officer but some 'proxy' of the government.[2]A integration of government can provide more opportunities for community members to report and resolve issues.

- Standardize law and regulation can restrain rule-breaking behaviour.

- develop national strategies for land allocation to manage land allocation into a sustainable strategy

- Limiting the plantations only in an appropriate area, claiming 'conservation district'. [10]

- classifying areas as forest or non-forest zones.

- Developing a map of traditional or customary land tenure.

- Develop multiple industries, create more employment to the local community, reduce dependency on natural resources.

- Prevent corruption

- Local representative participation

- Solve conflicts over land ownership and natural resource management from the perspective of community members. [1]

- ensure the right and territory of indigenous and local communities.

- ensure the legislative status of customary rights, and the identities as indigenous and community members.

- register and recognize female's right.

- Making oil palm 'smallholder-friendly'.[6]

- make oil palm a part of the agriculture system.

- secure tenure conditions are essential to ensure locals receive fair treatment from companies - this is undoubtedly the most important concerns

- protect the forest and mitigate carbon emissions

- stop expanding oil palm to peatland.

- protect lease allocations for further deforestation and degradation.

- prevention of wildfire, logging, and agriculture on forested lands within oil palm leases and protected areas.[4]

- Roundtable on Sustainable Palm oil (RSPO) is a voluntary certification system which aims to reduce the impact on biodiversity.[12]

A larger role for smallholders in a mixed farming system, rather than the present concentration on plantation monoculture, would be a more suitable goal for future oil palm production in Borneo.[6][13][14][15][16]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Naylor, R. L., Higgins, M. M., Edwards, R. B., & Falcon, W. P. "Decentralization and the environment: Assessing smallholder oil palm development in Indonesia". Ambio. 48(10),: 1195–1208.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Persoon, G. A., & Osseweijer, M. (2008). "Reflections on the Heart of Borneo". Tropenbos International. Vol 24.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 World Wide Fund for Nature (2009). "Threats to Borneo forests". WWF.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Carlson, K. M., Curran, L. M., Ratnasari, D., Pittman, A. M., Soares-Filho, B. S., Asner, G. P., ... & Rodrigues, H. O. (2012). Committed carbon emissions, deforestation, and community land conversion from oil palm plantation expansion in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), 7559-7564.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Earth Innovation Institute. (2015). Central Kalimantan Land Governance Assessment. doi: 10.1596/28514

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Cooke, F. M. (2013). State, communities and forests in contemporary Borneo. Canberra, ACT: Australian National University, E Press.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Forest Legality (2016). "Indonesia Laws & Regulations".

- ↑ The Gecko Project. "The making of a palm oil fiefdom".

- ↑ "Indonesian palm oil company embroiled in lawsuit for burning forest in Kalimantan". Illegal Deforestation Monitor. 2019.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gokkon, B. (2019, August 9). A remote Indonesian district juggles road building with nature conservation. Mongabay News & Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline. Retrieved from https://News.mongabay.com/2019/08/a-Remote-Indonesian-District-Juggles-Road-Building-with-Nature-Conservation/?n3wsletter&utm_source=MongabayNewsletter&utm_campaign=ff76d03ad3Newsletter_2019_09_05&utm_medium=Email&utm_term=0_940652e1f4-ff76d03ad3-67242283.

- ↑ Julia, W. B. (2012). Gendered experiences of dispossession: oil palm expansion in a Dayak Hibun community in West Kalimantan. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(3-4), 995-1016.

- ↑ Fitzherbert, E. B., Struebig, M. J., Morel, A., Danielsen, F., Brühl, C. A., Donald, P. F., & Phalan, B. (2008). How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Trends in ecology & evolution, 23(10), 538-545.

- ↑ Gaskell, J. C. (2015). The Role of Markets, Technology, and Policy in Generating Palm-Oil Demand in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 51(1), 29–45. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2015.1016566.

- ↑ Luke, S. H., Fayle, T. M., Eggleton, P., Turner, E. C., & Davies, R. G. (2014). Functional structure of ant and termite assemblages in old growth forest, logged forest and oil palm plantation in Malaysian Borneo. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23(11), 2817-2832.

- ↑ Persoon, G. A., & Osseweijer, M. (Eds.). (2008). Reflections on the Heart of Borneo (Vol. 24). Tropenbos International.

- ↑ Prabowo, D., Maryudi, A., & Imron, M. A. (2017). Conversion of forests into oil palm plantations in West Kalimantan, Indonesia: Insights from actors' power and its dynamics. Forest Policy and Economics, 78, 32-39.

| This conservation resource was created by Chang Liu, Zhenjie Bao. |