Course:FNH200/Lessons/Lesson 03/Page 03.2

3.2 Sensory Properties of Foods

Sensory evaluation is defined as a scientific discipline used to evoke, measure, analyze and interpret reactions to those characteristics of foods and materials as they are perceived by the senses of sight, smell, taste, touch and hearing.

Sensory evaluation of foods is widely used in the food industry as an important tool for: new product development, product matching, shelf-life studies, product reformulation, quality control, and consumer preference, among others.

What makes us decide on the type of food we consume?

Our decisions to consume a particular food item or combination of food items are based in part on nutritional factors but for the most part are often driven by sensory characteristics of the foods.

In order to better understand the concept of sensory properties of food, you should do the following:

- Make a selection of a food item in the grocery store or at your dinner table, consciously thinking about your approach to food selection.

- What are your basic criteria for accepting a particular food item?

- Follow the guidelines below to help you.

- Our first step in selecting a particular item is based upon appearance of the food (colour, shape, size, gloss). For example, if a new variety of orange were offered for sale we might reject that orange if it was red instead of orange in colour. We will also reject a strawberry that was green instead of red, thinking that it is not ripe.

- If the appearance of the food item is acceptable then the next step in the selection process is to determine the odour of the food through our sense of smell. For example, the aroma of fresh baked bread and cooked bacon.

- If that is acceptable we then examine the texture of the food through the sense of touch. For example, fresh bread has a soft texture, the crispiness in a potato chip, the thickness of maple syrup.

- Finally we decide whether to put the food item in our mouth in order to determine the flavour and texture in the mouth.

If any of the previous parameters noted above fall outside of our preset limits of acceptable quality for that particular food item we will reject that food item. The interrelationships among various sensory factors are shown in Figure 3.1.

Appearance Factors

Our perception of the appearance of a food is governed by a number of factors such as size, shape, colour, gloss, consistency, and presence of defects (e.g. mould on an orange; bruises on an apple).

When you watch television or read a magazine next time, pay particular attention to the food advertisements and determine how the advertising appeals to your senses. Advertisements describing the snap, crackle and pop of a breakfast cereal, the crunch of a particular brand of pickle, the thick consistency of a particular brand of catsup or the refreshing, clean flavour of a particular brand of soft drink are designed to appeal to the senses we use in making food selections.

Appearance factors are used as a measure of food quality. Thus mould growing on an orange is indicative of a spoiled product. Bruises on an apple or peach are indicative of poor handling and storage. The bright, shiny red and green of a freshly picked apple are indicative of freshness and superior quality.

This is one of the reasons why appearance of food products, whether produced by a food processor, a restaurateur or by yourself in your home receive a great deal of attention.

Textural Factors

Textural parameters are often used in food selection and in food quality measurement. Four examples of textural parameters are shown in Figure 3.2.

When you select bread and buns by gently squeezing them you are applying a measurement of texture, that is the resistance of the bread to deformation under an applied force and also the ability of that bread to regain its shape after the force is released. The fresher the bread the less force required to deform it while an older loaf of bread will appear "tougher" because the starch has begun to undergo retrogradation (Lesson 2) and thus the bread does not appear to be as soft and fresh.

We sense the toughness of meat when we cut it with a knife and with our teeth and facial muscles when we chew it. The more force required to cut the meat, the less tender the cut and our perception is that of the meat is of lower quality.

| Want to learn more? |

|

Flavour Factors

Flavour is a sensation made up of a combination of two senses: FLAVOUR = TASTE + AROMA (SMELL). In order to perceive a full bodied flavour, we need both the perception of TASTE and AROMA.

To elicit a taste sensation, a substance must be water-soluble and it must interact with the appropriate sensory receptors on the tongue.

Taste is detected in the mouth and primarily on the tongue.

To elicit aroma, substances must be fat soluble and volatile in order for them to interact with the odour or aroma receptors in the olfactory region of our nasal passages. Aromas of foods are a complex mixture of chemicals, which are often present in foods in very low concentration. Aroma constituents are a very important part of foods in relation to our perception of food quality.

When we have a cold, why does food seem bland?

When you have a cold and your sinuses are congested, food often has a bland flavour, basically being a combination of saltiness, sourness, sweetness and bitterness, which are the basic tastes.

Because your sinuses are congested you do not detect odour or only detect a very small amount of odour when consuming the food and thus it appears to be bland.

Description of the taste receptors

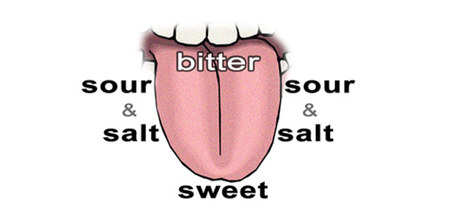

There are four recognized taste sensations: sweet, salty, sour and bitter. Some researchers recognize a fifth taste, called "umami". A diagram of the tongue with the locations of the four basic types of taste receptors is shown in Figure 3.3 - in fact, more recent research suggests that the four types of taste receptors are not as localized as shown in this figure, although they are more predominant in those locations.

Take a look at the artistic rendition of a taste bud in the article "Anatomy of Taste" published in Popular Science; Nov2007, Vol. 271 Issue 5, p48-49. Are you a "supertaster"?

Sweet

Sweet sensations are elicited by simple sugars, especially monosaccharides; the sweetness of oligosaccharides decreases as the number of sugar residues increases. Sugars are not the only sweet compounds. Some amino acids such as glycine are sweet. Some peptides (composed of two or more amino acids) are sweet; a notable example is Aspartame.

Aspartame, the low-calorie sweetener discussed earlier in this Lesson, is a dipeptide made of aspartic acid and phenylalanine, two amino acids commonly found in proteins in foods.

Other sweeteners include the synthetic compounds such as cyclamate and saccharin, which are neither amino acids nor carbohydrates. There are other compounds such as chloroform and lead acetate, which are sweet but not used as sweeteners!

Salty

Only one compound, namely sodium chloride, produces a pure salty taste. Compounds such as potassium chloride, often an ingredient in salt substitutes, produces a salty as well as a bitter taste. This is one of the reasons why it has been very difficult to formulate a palatable salt substitute for individuals on low sodium diets. It is not the sodium portion or the chloride portion of sodium chloride that elicits the salty taste. It is the ionized molecule of sodium chloride that it required for the production of a salty taste. Thus sodium sulphate is bitter but only slightly salty while calcium chloride is very bitter and cesium chloride is sweet.

Sour

Sour tastes are produced by protonated organic and inorganic acids. Citric, tartaric, malic, lactic, fumaric, acetic and phosphoric acids produce a sour taste and are commonly found naturally in many acidic foods and are also used as acidulants in foods. The acid taste of vinegar is due to acetic acid. You can probably recall many instances where you use vinegar to impart an acid taste to a food.

Bitter

Compounds that are bitter are typically alkaloids such as caffeine (in coffee and tea), theobromine (in chocolate) and solanine (a naturally occurring toxicant in green potatoes). Some salts such as sodium sulphate and calcium chloride are bitter, as are some amino acids and peptides. "Bitter peptides" contribute to the sharpness and bitterness of aged Cheddar cheese.

Umami

Umami is described as a "savoury" and "delicious" sensation, and is associated with compounds known as "Flavour Enhancers or Potentiators". Flavour enhancers are compounds that elicit no taste of their own at low concentrations, but can modify the perceived intensity or quality of the taste produced by another substance.

A typical example is monosodium glutamate, more commonly known as MSG. It apparently binds to the taste receptors in the tongue and causes an enhancement of taste sensations. Other flavour enhancers are the 5'-nucleotides such as inosine 5'-monophosphate, which enhances meaty flavour.

MSG has no effect on the aroma of a food. It enhances meat and vegetable flavours but does not enhance the flavour of acidic foods such as fruit, bakery products or sweet products. Enhancement of meaty flavours occurs at MSG concentrations below the level where MSG itself produces a typical taste sensation. MSG suppresses hydrolysed vegetable flavours (bitter) and sulfur or burnt cabbage flavour notes in foods.

| Want to learn more? |

|

Maltol, is also considered as a flavour enhancer. It modifies the flavours of soft drinks, fruit drinks, jams and other high carbohydrate foods. However, it does not elicit an "umami" (savory) sensation!

Other sensations perceived in the mouth/tongue:

Some specific chemical components of foods may lead to warming, cooling or other sensations in the mouth, tongue and lips.

- Astringency is more of a "physical" sensation described as puckering in the mouth; it is most often attributed to tannins or polyphenols of high molecular weight.

- Pungency is the term used to describe the sensation of "spicy heat" in the oral cavity. A well known example of pungent substances is the capsaicinoid family of molecules, such as capsaicin, found in chili peppers.

- In contrast, the sensation of coolness is a familiar one to you if you like to chew gum. Key compounds responsible for the cooling effect are menthol and its isomers. Various sugar alcohols such as xylitol and sorbitol also produce a cooling effect.

From the preceding discussion you should have some appreciation of the fact that sensory parameters of foods are very complex.

Our perception of the sensory properties of foods are dependent not only on the chemical and physical properties of the food but also on psychological factors as well.