Course:EOSC311/2024/How Graphite Changed the Literary World

Summary

Many writers use graphite pencils to create their work, but the connection between this geological resource and literature itself is not always so clear. Graphite is the soft, crystalline form of carbon used in pencils and known for its ability to leave dark marks upon writing surfaces [1], and literature is the study of written works like poetry, plays, and novels of fiction. This article will explore the link between the pencil and literature, discuss the discovery of graphite, how it is mined and made into pencils, and conclude with a deeper connection between this mineral's development and my own experiences as a student of literature.

Literature Connection

The Pencil's Place in the History of Writing

Today, many writers use computers, tablets, and other electronic resources to produce their writing [2], and many of us use electronics to read the writing that those authors create. These technologies are fast, efficient, and cost nothing after that of their initial purchase. Writing is more accessible and equitable than ever in our modern world, but this was not always the case [2]. Before both literacy and technology exploded among our population, people wrote with quills and ink, before that with reed pens or metals like gold or bronze [3], and even before that with charcoal and other minerals used to make cave paintings [4]. The dissemination of knowledge through writing, drawings, and carved tokens representing commodities has always been advantageous to our species’ communication, evolution, and survival [5], so the concept of making a physical mark in order to leave a message, impart an idea, or remember something has been happening for much of human history [2]. Today, the vast majority of our world is literate (87.01% globally) [6], with pens and pencils having become both omnipresent and inexpensive [2]; writing and communication are no longer such a privilege as they once were. But prior to the 18th century, access to writing utensils and literacy was reserved mostly for the upper class and select groups of people who were trained to wrote professionally [7]. Many factors have played a role throughout history in the widespread increase of education and literacy [7], and among those factors is the invention of the graphite pencil [2]. In addition to the difficulty of carrying around pots of ink and quills, the ink, paints, and quills themselves were also expensive and needed to be handmade, keeping writing out of the hands of the common people [2]. Surfaces like clay or wax tablets and papyrus on which people in these early centuries wrote were also more difficult and costly to prepare [2]. Pencils permitted people to write down their thoughts at any time (provided they had some sort of notebook on hand), and allowed for uninterrupted writing as the pencil did not need to be sharpened as often as a quill needed to be dipped into ink or have its tip adjusted with a knife [2]. With help from the invention of the pencil, writing became both easier and more readily available to the masses [2].

I have chosen to explore this connection between literature and the geological resource graphite because I myself am a writer and literature major, and I found that I had never before considered how impactful the pencil's invention was on global literacy as well as the lives of some of my favourite authors whom I have studied throughout my degree. One of our course's modules focused on the mining of diamonds, and I think graphite can be thought of a bit like the forgotten form of carbon. Just as graphite is known for its ability to leave a mark, the "mark" an author leaves upon the world is the writing they create, and that can be as beautiful as the coveted diamonds we learned so much about. With writing we can alter the world, preserve stories, share information, and when writers write with pencil, it is the mineral graphite which enables them to leave something of themselves behind.

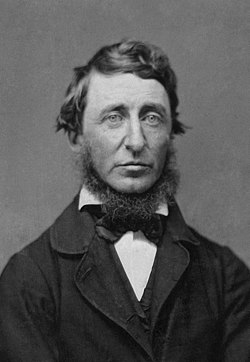

The Pencil Maker's Son

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was an American naturalist, philosopher, writer of essays, poems, and novels, as well as an incredibly important figure in literary history [8]. His work was rooted in the connection between nature and the self, as well as the self-reliance of individuals, and he wrote prominently in favour of abolition [8]. He was also the son of John Thoreau who established one of the most well-known pencil manufacturing facilities in America: The Thoreau Pencil Company [8]. Thoreau himself contributed to the evolution of the pencil, aiming to improve upon his father’s design, as he developed a way to produce smoother, more durable pencils by mixing specific portions of clay with more finely ground graphite [2]. This technique was also used earlier by the French pencil-maker Nicholas-Jaques Conté, who is credited with the method's invention [2]. Thoreau was successful in his pencil improvements and the company grew to be favoured in America, which had formerly preferred British-made pencils [2]. Thoreau is one of several writers said to have preferred writing his own work in pencil over quilled ink [9]. Among his more modern company in this proclivity for pencil are famed authors Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, and Margaret Atwood [9]. Thoreau likely wrote his early drafts using pencil during his time living in the woods of Maine, where he wrote his most well-known book, Walden, about the contemplation of life and man’s role in the natural world. Perhaps this would have been more difficult for him if he had instead been forced to carry an ink pot and a quill to record his notes. The success of The Thoreau Pencil Company is what ultimately funded the publication of Henry's two most famous books, so his work may not have reached the world if not for the pencils he helped create and always carried [10].

“If you write with a pencil you get three different sights at it to see if the reader is getting what you want him to. First when you read it over; then when it is typed you get another chance to improve it, and again in the proof. Writing in pencil gives you one-third more chance to improve it” – Ernest Hemingway [9].

What is Graphite?

Graphite is a natural form of carbon created under high temperature and pressure conditions [1]. Carbon can also form diamonds, but graphite is the more stable form, characterized by its layered structure, hexagonal crystalline system and resulting softness (Mohs scale hardness of 1.5) [11]. Graphite is used to form the cores of pencils, as well as in some coatings, batteries, lubricants, steelmaking and more [1]. The mineral is also a good conductor of heat and electricity [11]. Graphite forms during the “metamorphosis of sediments containing carbonaceous material, by the reaction of carbon compounds with hydrothermal solutions or magmatic fluids, or possibly by the crystallization of magmatic carbon” [11]. Graphite was initially mistaken for lead, leading to the name which still follows graphite “lead” pencils to this day [12], despite the fact that they do not contain lead.

The Discovery of Graphite

There is some evidence which suggests that graphite was used by humans as far back as 500 BC in ceramic making as well as early writing [13], but the first large-scale discovery of natural graphite occurred in Grey Knotts in Seathwaite of Borrowdale, Cumbria, England [14]. Though the exact date and circumstances of the discovery are unconfirmed, sources place it somewhere between 1500 and before 1565 [14] [12]. According to legends, the graphite may have been unearthed when a windy storm knocked over a tree, or during prospection for mining copper which was taking place in the same area at the time [12]. However it was found, the graphite discovered at this site was not only a massive quantity but extremely pure and solid, making it easy to be cut into sticks and capable of leaving dark marks which could be rubbed away; farmers are said to have used it initially to mark their sheep [12]. The Grey Knotts deposit remains the only large-scale graphite deposit ever found in this type of pure, solid form [12]. Graphite would soon become extremely valuable when its use in the making of cannonballs began in the British military early in the 16th century [15] [13]. Graphite was in high demand by this time, leading the government to control mining operations at Grey Knotts, and the stealing and smuggling of graphite “wads” grew as their value did. It is interesting to think about this discovery’s connection to literature; the miners who smuggled wads of graphite out from the mines to be sold would have had no idea that they held in their hands a piece of the literary future. The same graphite which was used to shape cannonballs to be used in war would later write the stories of those very battles in the hands of authors and record keepers. In the same way a cannonball leaves its mark upon the ground, the graphite we hold today within our pencils can leave marks upon our pages. It's also interesting to consider how the account of this discovery (like so many moments throughout history) could have been better documented with greater literacy; had those who found this giant graphite deposit been in possession of the writing resources we have today, perhaps we would know even more about it and them!

How It's Made: Graphite to Pencil

Not all deposits of graphite reveal themselves as easily as the one discovered at Grey Knotts several hundred years ago. Before it can be made into pencils and other resources, graphite must be extracted from the Earth. Graphite is mined using both open pit mining and underground mining [1]. In open pit mining, rocks and minerals are separated from a large excavation site in the Earth [1]. Generally, the open pit method is chosen when the resources desired are close to the Earth’s surface and the material separating us from them underneath is thin [1]. Rocks are quarried, blasted, and drilled, and the graphite beneath is brought to the surface using locomotives or (in some developing countries) picked by hand before being pulled away in a cart [1]. Underground mining is done in cases where the graphite deposit is located deeper within the Earth in veins or beds, and it would not make economic sense to employ open pit mining techniques [1]. These graphite deposits are accessed through shafts created in the rock [1]. Graphite in this case is transported out from the shafts using conveyors before being processed [1].

Once the graphite is mined, it is blended finely and mixed with clay to specific ratios which determine how dark and hard the resulting pencil core will be [16]. This mixture is then made into long rods which are then cut to the desired length [16]. The pencil’s casing is cut from slats of wood (usually cedar, spruce, poplar, or pine) [17] , where groves are made to place the graphite in between two separate slats [16]. The graphite rods are then glued into the grooves and sandwiched with the other piece of wood before the pencil is dried, shaped, and coated with a protective lacquer [16].

Historically, pencils began as graphite wads simply shaped and wrapped with string, the string would be unwinded as the graphite was used, the earliest form of the “sharpening” process we know today [12]. Later, graphite would be cut into rods before being pushed into hollow twigs or reeds, which would need to be cut using a knife to be sharpened as needed [12]. In writings as early as 1609, there are mentions of “black-lead” used to draw maps and take notes, indicating that graphite’s discoverers initially believed it to be a more pure form of lead [12]. The development of enclosing graphite into wooden casings which could be sharpened more easily with knives was a major advancement of the pencil and is still essentially governed by the same principle techniques we use today [12]. By the 18th century, the process is documented as cutting graphite into long strips, cutting grooves into halves of wood, gluing the graphite into the groove, and then gluing another grooved piece of wood on top to seal the graphite in the middle [12].

Connections

In my own experience as a writer and reader of literature, pencils tend to enable creativity and freedom of expression. Knowing that any mark I make can be erased with ease is helpful in getting started on some of my own writing, and I always mark the books I read with a pencil so that I can later erase those notes and underlines if I want to. Of course, it is also quite simple to cross out what's been written in ink, but I think this certainly would have been more concerning in the days of expensive quills, ink pots, and paper surfaces. Today, it is perhaps easy to take these writing tools for granted or to view them as indefinite resources, but learning of the long process behind graphite's extraction and production has inspired me to use my pencils more, to take advantage of the softness and erasability of graphite.

I actually find that computer note-taking technology provides the same sort of freedom and creativity that pencils do since it's so simple to "erase" what you've written with a few strokes of the backspace key. Today, worry circulates among some circles of parents and educators that technological advancements in classrooms will lead to the loss of handwriting abilities among future generations [18]. Interestingly, these fears of literary advancements appear to be historically cyclical. In the age of Plato (~428 BC → ~348 BC), traditionalists are said to have feared that writing anything down would weaken our memories [2]. After the pencil's invention, many teachers allowed only the use of ink in their classrooms or outlawed erasers to keep students from becoming "reliant" on easy revision, fearing that their work would grow less premeditated if they were always able to edit it [2]. It is fascinatingly common for new technologies to be feared, and these past anxieties about pencils support the notion that, sometimes, these fears are not entirely necessary. In the modern classroom, free-writing exercises are a commonplace practice to get students started with writing (I have done many throughout my university years), the use of pencils is widely advised for school-aged children so that they can more easily fix their mistakes, and instructors often recommend beginning drafts of stories and poems in pencil.

I have studied Henry David Thoreau in my time at UBC, and I found his writing about the state of man within nature to be fascinating. I had no idea that his family was so involved in the American creation of pencils, or that he himself improved upon pencil-making techniques. William Faulkner and Margaret Atwood are two more authors I have read quite extensively in my literature studies, and discovering that they are among the great pencil-using authors makes me feel connected to them and their work through the pencils that I myself have made notes with in the margins of their books. Included in Atwood's "10 Rules of Writing" is to take two pencils with you to write on aeroplanes because "pens leak" [19], one piece of advice I think her graphite-using literary ancestors would heartily agree with.

Conclusion

Although only a small portion of the graphite mined worldwide is used for pencils, the impact pencils have had on the world of literature cannot be overstated. The pencil's introduction to the world meant that more people outside of high society circles gained access to writing tools and the potential for literacy, and graphite's erasability continues to be favoured by some of the most well-known authors in the world even amongst today's incredible technologies. Though production has been streamlined, the basic pencil-principles remain the same: graphite between two slabs of wood, sharpened as needed. While some modern traditionalists worry that technology's introduction to writing and literature will degrade the quality of work produced and erode the skills of students, the history of graphite pencils shows us that, perhaps, these traditionalists' fears will not materialize. Even the name "graphite" comes from the Greek word "graphein" meaning: to write [20]; graphite has certainly left its mark in the world of literature.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Stewart, David (2017). "How Is Graphite Extracted?". Sciencing.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Baron, Dennis (1999). "From pencils to pixels". Passions pedagogies and 21st century technologies. Utah State University Press. pp. 15–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt46nrfk.4 Check

|doi=value (help). - ↑ "WRITING INSTRUMENTS over 6000 YEARS". ergocanada.

- ↑ "Prehistoric pigments". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ↑ Wright, James (2014). "The Evolution of Writing". Denise Shmandt-Besserat, University of Texas.

- ↑ "World Literacy Rate 1960-2024". macrotrends.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Houston, Rab (2008). "Literacy and society in the west, 1500–1850". Social History (London). 8: pp. 269-293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03071028308567568 Check

|doi=value (help) – via Taylor & Francis.CS1 maint: extra text (link) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Furtak, Rick (2005). "Henry David Thoreau". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Gouty, Melissa (2021). "Why Great Authors Often Choose to Write With Pencils". LiteratureLust.

- ↑ "How the Thoreau Pencil Wrote, and Paid for, Walden". New England Historical Society.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2024). "Graphite". Britannica.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 Voice, Eric H. (1950, Published online 2014). "The History of the Manufacture of Pencils". The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology. 27: pp. 131-141 – via Taylor & Francis. Check date values in:

|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra text (link) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Wat On Earth - Graphite". University of Waterloo. March 1 2006. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The Graphite Pencil". The British Museum, BBC. 2014.

- ↑ Baker, Ian (2018). Fifty Materials That Make the World. Springer International Publishing. pp. 81–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78766-4_16 Check

|doi=value (help). - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "How a Pencil is Made". Musgrave Pencil Company. May 11, 2019.

- ↑ "How Are Pencils Made? The Ultimate Guide". HoneyYoung. March 24, 2023.

- ↑ Elwahab, Waleed A. (2023). "Detrimental Impact of Technological Tools on Handwriting". Journal of Language and Linguistics in Society. 4: 31–41 – via JLLS.

- ↑ Popova, Maria. "Margaret Atwood's 10 Rules of Writing". The Marginalian.

- ↑ "Graphite". Oxford English Dictionary.

- Katie Kwasnicki

| This Earth Science resource was created by Course:EOSC311. |