Course:CSIS200/2024/Wedding Ring

Introducing the Wedding Ring

| Key Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Social Construction | The process by which objects, concepts, or categories gain meaning and significance through collective human actions, cultural values, and societal norms, rather than having inherent meaning.[1] |

| Patriarchy | A social system in which men hold primary power and dominate roles in political, economic, and cultural spheres, often perpetuating gender inequality and subordination of women.[2] |

| Heteronormativity | The assumption that heterosexual relationships are the default, natural, or only legitimate form of partnership, often marginalizing LGBTQ+ relationships and reinforcing binary gender roles.[3] |

| Amatonormativity | The societal expectation that romantic, monogamous marriages are essential for personal fulfillment and success, often marginalizing those who are in non-monogamous relationships.[4] |

| Capitalism | An economic system in which private entities own and control production and trade for profit, often commodifying cultural and social practices, such as marriage and the wedding ring, to drive consumption and maintain economic hierarchies.[5] |

What is a Wedding Ring?

A wedding ring is a small round band made from metals like platinum, silver, or gold, often featuring diamonds or other gemstones set on top. It is typically worn on the "ring finger," the fourth finger on the left hand, based on the ancient belief that this finger contained a vein that connects directly to the heart, symbolizing love and connection.[7]

Historical Origins

Wedding rings have been worn for thousands of years; some of the earliest instances can be discovered in ancient Egypt, where they were given and received as symbols of commitment and eternity.[8] The Archduke Maximilian of Austria presented Mary of Burgundy with the first diamond engagement ring in 1477, gaining popularity in the late 15th century.[9] Due to their durability, diamonds have come to be associated with weddings and engagements, signifying the unbreakable love that many people still use today in weddings to represent love and commitment.

The Wedding Ring as a Symbol of social construction

The social construction of the wedding ring is influenced by patriarchy, which has traditionally perpetuated gendered power imbalances in marriage. For centuries, the wedding ring operated as a marker of women's subordination in a male dominated society.

The wedding ring serves as a socially constructed symbol, meaning it does not naturally symbolize love, commitment, or marriage; instead, these ideas have been attached to it through traditions, cultural values, and social expectations from patriarchy and heteronormativity. This symbolism also underscores how the institution of marriage has historically excluded same sex couples and reinforced restrictive ideals.[11] As Christiansen and Fischer (2016) explain, social construction is the process by which objects, concepts, and categories gain significance through collective human actions and cultural norms.[12]Though simply a circular band, the wedding ring derives its meaning entirely from these societal frameworks, making it a clear example of material social construction.

Patriarchal Influence

The social construction of the wedding ring is influenced by patriarchy, which has traditionally perpetuated gendered power imbalances in marriage. For centuries, the wedding ring operated as a marker of women's subordination in a male dominated society[2].

Ownership and Subordination

For instance, as discussed by Bahrami-Rad in 2021, the tradition of men giving engagement rings to women reflects a legacy of women being treated as property to be exchanged between fathers and husbands.[13]Russell (2010) further elaborates on this point. He argues that "the wedding ring historically functioned as a symbol of incapacitation and ownership, where women's social identity and worth were tied to their marital status rather than their individual autonomy".[14]

Through this framework, the wedding ring is more than a piece of jewelry; it reflects societal expectations that confined women to roles of submission and caregiving while men faced no symbolic constraints. This imbalance highlights the patriarchal influence of marriage traditions, showcasing how the meaning of the wedding ring has been constructed by a system that defined women's identities through marriage rather than their autonomy.

Heteronormativity Influence

Heteronormativity further reinforces the wedding ring as a socially constructed symbol, examining the idea that monogamous, heterosexual relationships are the only legitimate forms of partnership. Historically, marriage was exclusively defined as a union between a man and a woman, and the wedding ring became a cultural marker of this definition.[15] Before the legalization of same sex marriage in many countries, same sex couples were not only excluded from legal recognition but also denied access to the cultural symbols of marriage, including the wedding ring.

As Ambrosino (2017) observes, "symbols like the wedding ring serve as cultural gatekeepers, shaping who is considered worthy of societal acceptance and who remains marginalized" (p. 8).[16]

This exclusion reinforced systems of oppression, denying same sex couples the legitimacy afforded to heterosexual relationships. Consequently, the wedding ring became a symbol of heteronormativity, defining who was deemed acceptable within marriage while marginalizing those outside its narrow scope. By acting as a "cultural gatekeeper," the wedding ring becomes a tool for determining who is allowed entry into the socially sanctioned institution of marriage and, by extension, who is granted the privileges and respect that come with it. For much of history, same sex couples were excluded from this institution, not only denied legal recognition but also stripped of the societal approval and validation that the ring represents. Without access to this symbol, same sex couples were positioned as outsiders, marked by their inability to conform to the heteronormative ideal of partnership.

But same sex marriage has been approved already?

Even with the legalization of same sex marriage in many parts of the world, the wedding ring remains a socially constructed symbol tied to societal pressures and heteronormative expectations. Historically associated with heterosexual unions, it reflects and reinforces traditional binary gender roles within relationships.

For same sex couples, participating in this tradition often invites additional societal scrutiny. For example, Mahdawi (2016) surveyed 200 same sex couples to see how frequently they face intrusive questions like, "Who is the man in the relationship?" The study found that 78% of respondents had been asked this or similar questions, showing how central binary gender roles still are in society's view of marriage.[17]

These questions reveal society's expectation for same sex couples to mimic heterosexual dynamics, highlighting how the wedding ring, as a symbol of marriage, reinforces traditional heteronormative norms. While same sex couples can now participate in this tradition, they still face pressure to conform to binary gender roles, reflecting the wedding ring's ties to heteronormative and patriarchal ideals. As a socially constructed artifact, the wedding ring prioritizes heterosexual relationships, upholds traditional gender roles, and excludes those who challenge conventional standards of gender, sexuality, and love.[18]

Amatonormativity and Wedding Rings

Definition of Amatonormativity

Amatonormativity refers to the societal belief that romantic relationships, particularly monogamous marriage are essential for success and the ultimate goal in life, has deeply shaped the cultural and economic significance of the wedding ring. This ideology prioritizes traditional romantic relationships as the sole marker of a meaningful life, marginalizing those who fall outside its narrow boundaries.[4] Capitalism has further reinforced amatonormativity by commodifying marriage through symbols like the wedding ring.[5]

The Duality of Conformity and Exclusion

Amatonormativity has historically excluded same sex couples from marriage, further marginalizing them and denying their partnerships the status and benefits granted to heterosexual unions. For centuries, same sex relationships were criminalized, with laws explicitly barring queer couples from marriage and its associated legal and social benefits.[20]In the U.S., the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) of 1996 defined marriage as a union between one man and one woman, denying same sex couples access to over 1,000 federal protections, such as tax benefits and spousal Social Security.[20]

The discriminatory Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was overturned by the Obergefell v. Hodges decision in 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court guaranteed same sex marriage as a constitutional right under the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses. This decision required all states to both license and recognize same sex marriages.[21] However, even in countries with legal recognition, amatonormativity continues to perpetuate inequalities. A 2021 survey found that 37% of respondents in countries where same sex marriage is legal still viewed these unions as "not equal" to heterosexual marriages, citing tradition and religious values.[22] This lack of social acceptance forces same sex couples to navigate a system privileging heterosexual norms, where symbols like the wedding ring reinforce exclusion.

Exclusion Through Marketing and Representation

The capitalist commodification of marriage through wedding rings also marginalizes same sex couples by framing romantic success around heteronormative ideals.[23] Wedding rings are marketed as symbols of love, wealth, and commitment, rooted in traditional gender roles where men are providers and women are caregivers. For same sex couples, this framework is inherently exclusionary.

A 2022 study by Smith (2020) found that 88% of wedding ring advertisements targeted heterosexual couples, emphasizing traditional gender roles like men proposing to women with expensive rings. Only 12% included same sex couples, and these often reinforced heteronormative dynamics by assigning "masculine" and "feminine" roles.[24] The lack of authentic LGBTQ+ representation perpetuates the idea that wedding rings are constructed by a heterosexual institution.

Kay Jewelers’ 2020 commercial, ended with the tagline "Because every love story deserves a perfect ending"(2:27). Exemplifies the systemic erasure of queer identities within marriage by exclusively featuring a heterosexual couple. This portrayal reinforces the notion that only heterosexual unions are worthy of societal celebration and validation, reflecting the exclusionary ideals critiqued by Ward (2020) in their discussions of heteronormativity and amatonormativity. The ad depicts a traditional romantic proposal, presenting the engagement ring as the ultimate symbol of love, happiness, and societal legitimacy while promoting marriage as a universal life goal. However, the absence of LGBTQ+ representation perpetuates the idea that marriage is inherently a heterosexual institution, marginalizing same sex couples and their relationships.[25] By framing heterosexual unions as the normative standard of love, this advertisement operates as a cultural gatekeeper, using the wedding ring to validate certain relationships while excluding others. This ad provides a visual, real-world example of the heteronormative and amatonormative ideals critiqued by Ward, illustrating how mainstream media continues to reinforce these exclusionary frameworks. As such, it is a critical source for my research, highlighting how wedding ring advertisements not only commodify marriage but also sustain cultural narratives that marginalize LGBTQ+ individuals and relationships.

Capitalist Commodification of Wedding Rings

Marketing campaigns have elevated the wedding ring from an accessory to a marker of social legitimacy, suggesting that love and commitment are only valid when accompanied by a material purchase. For instance, the De Beers advertising campaign in the 1940s popularized the idea that "A Diamond is Forever," making the diamond ring synonymous with eternal love—a notion designed to increase consumption.[26]

This commodification has broader implications for understanding love and relationships in society. The wedding ring is no longer just a personal symbol of affection or commitment. Instead, it has become a marker of social legitimacy. Through advertising, capitalism has linked happiness, success, and social status to marriage, specifically to purchasing and wearing a wedding ring. This cultural messaging enforces conformity by suggesting that a "proper" relationship must follow a specific formula: a public declaration of commitment sealed with a costly symbol. Those deviating from this norm are often seen as less legitimate.

In essence, capitalism has turned the wedding ring into both a cultural and economic tool. It enforces conformity by dictating what love and commitment should look like and ties personal relationships to consumerism. This commodification reduces relationships to simple transactions, where love is validated only through material displays, making the wedding ring not just a personal choice, but a deeply ingrained social expectation.

Economic Barriers to Participation

The marginalization of same sex couples, particularly queer women, is worsened by the economic barriers tied to wedding rings. In 2022, the average cost of an engagement ring in the U.S. was $5,900, a price many queer women struggle to afford due to systemic discrimination and the gender wage gap.[28] On average, queer women earn less than $25,000 annually, compared to $51,400 for heterosexual women. Women and gay men are also overrepresented in lower-paying service jobs, further deepening financial disparities.[29] For queer women, these economic inequalities make it difficult to meet societal expectations tied to expensive wedding traditions, such as purchasing engagement rings.

Unlike gay men, who often benefit from male privilege and higher wages, queer women are disproportionately impacted. As Maria Gonzalez (2021) states,

“The capitalist obsession with the wedding ring as a marker of romantic success commodifies love while excluding those who cannot afford to participate, particularly LGBTQ+ women”(p.31).[30]

By tying love and commitment to material wealth, capitalism makes marriage and the wedding ring a tool for maintaining social hierarchies. Ultimately, the wedding ring reinforces amatonormativity and heteronormative ideals, privileging heterosexual, monogamous relationships while marginalizing queer women. Its commodification of love perpetuates exclusion, forcing same sex women to navigate a system that devalues their relationships unless they conform to heteronormative standards. In doing so, the wedding ring serves as a mechanism for upholding inequality and social conformity.

The Unequal Fight for the Wedding Ring: Past Struggles and Present Threats to Marriage Equality

Historical Exclusion

Throughout history, same sex couples have faced numberless marginalization in their fight for the basic right to marry, a right symbolized by the wedding ring. For decades, societal norms and legal systems denied queer couples the legitimacy and recognition afforded to heterosexual unions, framing marriage as an institution exclusive to men and women.[22]This exclusion not only stripped same sex couples of the ability to celebrate their love publicly but also deprived them of the legal and economic benefits tied to marriage. The road to achieving marriage equality was long and fraught, culminating in the landmark 2015 Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, which finally guaranteed the right to marry for same sex couples across the United States. Yet, even with this hard-won victory, marriage equality remains under threat today, with the wedding ring still not guaranteed for all.[31]

Legal Progress and Ongoing Threats

Marriage equality remains vulnerable today. The 2022 Respect for Marriage Act requires the federal government to recognize same sex marriages and ensures states honor marriages performed elsewhere. However, it does not require states to issue marriage licenses to same sex couples. [31]If Obergefell v. Hodges were overturned, as Justice Clarence Thomas suggested in his 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization opinion, same sex marriage bans in 30 states could be reinstated, making marriage illegal for same sex couples in those states. This risk highlights how fragile progress is and raises concerns about the future of marriage equality.[32]

Political Challenges

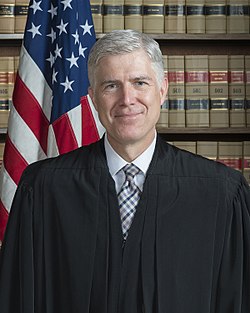

Trump’s appointment of three conservative justices—Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—created a 6-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court. This shift has also emboldened key figures, including Samuel Alito, and conservative politicians like Senator Ted Cruz, to question or oppose the constitutional foundation of Obergefell v. Hodges, the landmark decision that legalized same sex marriage nationwide.[32]Here’s how each has contributed to the growing threat to marriage equality:

| Neil Gorsuch | Brett Kavanaugh | Amy Coney Barrett | Ted Cruz | Samuel Alito |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| In his 2022 opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Thomas explicitly suggested reconsidering Obergefell v. Hodges, calling for the Supreme Court to revisit rulings on substantive due process rights, including same sex marriage.[32] | In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Kavanaugh argued that returning decisions on contentious issues like abortion to the states was the proper constitutional approach,[38] raising concerns that he might apply the same reasoning to same sex marriage. His silence on the matter leaves significant uncertainty about his position if Obergefell were challenged. | Barrett has a history of opposing LGBTQ+ rights prior to her appointment. She has previously been associated with legal groups that challenge same sex marriage, such as the Alliance Defending Freedom, which has labeled Obergefell a threat to religious liberty.[39] | Ted Cruz described Obergefell as “clearly wrong” and stated, “It was the court overreaching.” He has consistently supported efforts to roll back marriage equality, aligning with conservative legal arguments against same sex marriage.[40] | Alito, alongside Thomas, has criticized Obergefell, calling it “undemocratic” and arguing that the ruling represents judicial overreach, implying it should be overturned.[31] |

For same sex couples, the wedding ring symbolizes far more than love, it represents dignity, equality, and the recognition of their humanity. Yet, both historically and in the present, the ability to marry has been treated as a privilege rather than a right, granted to some and denied to others. The current political climate reveals how fragile this progress remains. The hard fought gains of marriage equality could be undone, leaving millions of same sex couples to once again fight for the right to love equally.

Author Bio

I am a university student born and raised in Vancouver, majoring in Sociology at UBC. As the child of immigrant parents. Growing up, I was always curious about how societal norms shape our identities, especially when it comes to love, family, and acceptance. My passion for exploring LGBTQ+ rights came both from academic interest and also from personal experiences.

A close family friend of my mother, who is in a same sex relationship, adopted a child in china, who became my childhood best friend before we moved. I remember sitting with them one evening as they shared the challenges they faced, from navigating adoption laws biased against LGBTQ+ couples to dealing with societal judgment. They spoke about how often they are questioned about their ability to provide a “normal” family life for their child, and how they have to constantly prove themselves as loving and capable parents.

Their story inspired me to research the systemic inequalities faced by same sex couples and to better understand how symbols like the wedding ring perpetuate exclusion. As someone with Chinese heritage, I also think about how same sex relationships remain heavily stigmatized in China today, where LGBTQ+ rights are far from recognized. This contrast between cultures and experiences motivates me to advocate for a world where love and family are not bound by outdated norms. Through my work, I hope to contribute to the fight for equality and amplify the voices of those who continue to face these challenges every day.

- ↑ Christiansen, L. D., & Fischer, N. L. (2016). Working in the (social) construction zone. Introducing the New Sexuality Studies, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315697215-2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Beechey, V. (1979). On patriarchy. Feminist Review, 3(1), 66–82. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.1979.21

- ↑ Parker, H. (2015). Heterosexuality. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.3083

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ward, J. (2020). The tragedy of heterosexuality. New York University Press.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Howard, V. (2003). A “Real man’s ring”: Gender and the invention of tradition. Journal of Social History, 36(4), 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2003.0098

- ↑ Setterfield, R. (2019, June 10). Maximilian giving a diamond ring to Mary of Burgundy [Image]. Retrieved from hemmahoshilde.wordpress.com

- ↑ Oldenburg, A. (2024, August 25). Diamond Nexus. What is a Wedding Band: History, Types, and More - Diamond Nexus. https://www.diamondnexus.com/blog/all/what-is-a-wedding-band?

- ↑ Yarbrough, M. (2020, June 14). A quick history of wedding rings: From ancient egypt to the modern day. Rustic and Main. https://rusticandmain.com/blogs/stories/history-of-wedding-rings

- ↑ Kreienberg, M. (2024a, September 11). The surprising history of engagement rings. Brides. https://www.brides.com/story/history-of-the-engagement-ring

- ↑ Rivera, A. (2024, May 6). Wedding ring [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/wearing-your-engagement-ring-on-wedding-day-5509278

- ↑ Schweingruber, D., Cast, A. D., & Anahita, S. (2007). “A story and a ring”: Audience judgments about engagement proposals. Sex Roles, 58(3–4), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9330-1

- ↑ Christiansen, L. D., & Fischer, N. L. (2016). Working in the (social) construction zone. Introducing the New Sexuality Studies, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315697215-2

- ↑ Bahrami-Rad, D. (2021). Keeping it in the family: Female inheritance, inmarriage, and the status of women. Journal of Development Economics, 153, 102714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102714

- ↑ Ross Russell, R. (2010). Gender and jewelry: A feminist analysis.

- ↑ Parker, H. (2015). Heterosexuality. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.3083

- ↑ Ambrosino, B. (2017, March 15). Invention of "heterosexuality." OutHistory. https://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/heterohomobi/ambrosino

- ↑ Mahdawi , A. (2016, August 23). “who’s the man?” why the gender divide in same-sex relationships is a farce. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/aug/23/same-sex-relationship-gender-roles-chores

- ↑ Rostosky, S. S., Riggle, E. D., Rothblum, E. D., & Balsam, K. F. (2016). Same-sex couples’ decisions and experiences of marriage in the context of minority stress: Interviews from a population-based longitudinal study. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(8), 1019–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1191232

- ↑ Wilson, M. (2013, March 27). Defense of Marriage Act [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-xpm-2013-mar-27-la-me-ln-prop-8-doma-scotus-20130327-story.html

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Kelly, K. C. (2018, February 17). Defense of marriage act. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Defense-of-Marriage-Act

- ↑ Scalia, J. (2016, February 24). Obergefell v. Hodges. Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/14-556

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gubbala, S. (2023, November 27). How people around the world view same-sex marriage. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/11/27/how-people-around-the-world-view-same-sex-marriage/

- ↑ Adhikary, R. P. (2023). Commodification of human emotion and marriage in capitalism (a reading of Probst’s the marriage bargain from a Marxist perspective). Isagoge - Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(1), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.59079/isagoge.v3i1.186

- ↑ Smith, O. (2020, November 16). Engagement ring marketing is excluding pretty much everyone except for White Women. Grit Daily News. https://gritdaily.com/engagement-ring-marketing/

- ↑ Kay Jewelers. (2024, March 1). Engagement rings at KAY [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8DEKT_3GVY

- ↑ Cook, A. (2023, February 11). Explore the essence of natural diamonds: A diamond is forever. Explore The Essence of Natural Diamonds | A Diamond Is Forever. https://adiamondisforever.com/

- ↑ Wilson, M. (2013, March 27). A Diamond Is Forever slogan by De Beers [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://theconsumerbehaviorlab.com/diamonds-romance-and-the-wheel-of-fortune.php?play=true

- ↑ Rumsey, E. (2024, October 8). Here’s the average engagement ring cost by state, according to real couples. theknot.com. https://www.theknot.com/content/how-much-to-spend-on-engagement-ring

- ↑ Rumsey, E. (2024, October 8). Here’s the average engagement ring cost by state, according to real couples. theknot.com. https://www.theknot.com/content/how-much-to-spend-on-engagement-ring

- ↑ Moosa, T. (2013, November 2). A man’s perspective on why engagement rings are a joke. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/02/dont-buy-an-engagement-ring

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Elliott, P. (2024, March 14). Why same-sex marriage is on the ballot in 2024. Time. https://time.com/6899864/same-sex-marriage-supreme-court-biden-trump/

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Beran, L. (2024, October 30). Why marriage equality is back on the ballot. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com

- ↑ Jantzen, F. (2017, May 25). Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch Official Portrait [Photograph]. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved from https://www.oyez.org/justices/neil_gorsuch

- ↑ Schilling, F. (2018, December 10). Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh Official Portrait [Photograph]. Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved from https://www.oyez.org/justices/brett_m_kavanaugh

- ↑ Malehorn, R. (2018, August 24). Amy Coney Barrett in 2018 [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://rachelmalehorn.smugmug.com/Portraits/i-znD3NgL

- ↑ U.S. Senate Photographic Studio. (2019, January 31). Ted Cruz official portrait, 2019 [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.cruz.senate.gov/files/images/

- ↑ Petteway, S. (2007). Official portrait of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Alito [Photograph]. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved from https://api.oyez.org/sites/default/files/images/people/samuel_alito_jr/

- ↑ Biskupic, J. (2023, March 16). Analysis: Kavanaugh and Alito said judges would be out of the abortion equation. that’s not the case | CNN politics. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/16/politics/brett-kavanaugh-samuel-alito-abortion-pill-hearing/index.html

- ↑ Hercom, J. (2020, September 22). Amy Coney Barrett is an absolute threat to LGBTQ rights. HRC. https://www.hrc.org/news/amy-coney-barrett-is-an-absolute-threat-to-lgbtq-rights

- ↑ Jasque, K. (2022, July 18). Sen. Ted Cruz says Supreme Court “clearly wrong” in decision legalizing same-sex marriage. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/sen-ted-cruz-says-supreme-court-clearly-wrong-decision-legalizing-sex-rcna38588