Course:CONS370/Projects/Vilcabamba River vs. the Provincial Government of Loja: exercising the constitutional Rights of Nature in Ecuador

| Theme: Rights of Nature | |

| Country: Eduador | |

| Province/Prefecture: Loja | |

This conservation resource was created by Abigail Muscat, Hannah Jay, & Rebecca Hilpert. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to examine the relationship between Indigenous rights and values and the Rights of Nature (RoN) recognized in the 2008 constitutional reform in Ecuador. We will provide an introduction of how the constitutional reform came to be, focusing on the ideological framework. We will then analyze the specific case of the Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja, the first successful legal case in Ecuador where the constitutional Rights of Nature were implemented. We will provide an overview of the case, identify key stakeholders involved and their relative power dynamics, discuss the legal process, and address the successes and shortcomings of this win. Acknowledging the flaws in the representation of Indigenous rights with regards to RoN, some recommendations for implementing RoN on a wider scale will be discussed. Overall, we aim to demonstrate how RoN and the success of the Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja case provides a framework for the incorporation of Indigenous values in colonial systems and a platform for local, national, and international reconciliation.

Keywords: Rights of Nature, Vilcabamba River, Province of Loja, Ecuadorian Constitution, Indigenous world-view

Background: Constitutional Reform

The 2008 constitutional reform in Ecuador came to be as a result of several fundamental components. In the two to three decades leading up to 2008, there was an increasing concern about the relationship between industrial development and the environment, and Indigenous groups were demanding for Ecuador to be recognized as plurinacionalidad, or a plurinational state [1]. In short, this means that Indigenous communities work alongside non-Indigenous communities in political forums. This induced an intense political climate. In 2006, the election of progressive, left-wing Rafael Correa for President meant that some of these concerns and tensions could be addressed through a radical shift away from traditional developmental models by formulating a new Constitution.1 As the first of its kind to recognize nature having rights, the Constitution proposed ideas that countered traditional Western understandings of who/what bears rights, and it contrasted economic models that relied heavily on the export of natural resources and extractive industries [1] (p. 938). The Western worldview can be described as containing “...neocolonial extractivist practices (that) are sustained by a particular conception of nature: a bunch of passive and agentless objects that are meant to satisfy human needs...” [2] (p. 137) as cited in [3] (p. 61). Alternatively, it is accepted that Indigenous People perceive nature as a living entity that exists alongside humans in dimensions of the same life cycle [3]. Overall, what the Constitution outlines about the Rights of Nature, as well as the process leading to its very creation, signifies a “... an instance in which indigenous politics influenced non-Indigenous systems of state authority” [1] (p. 939).

History of Environmental Movement in Ecuador

Environmental and social movements were brewing in Ecuador for decades leading up to 2008. The efforts of environmental activist groups and NGOs in this period laid a foundation for the Rights of Nature (RoN) movement, by pressuring the government to recognize international standards concerning sustainability and resource management. Historically, Ecuador has relied heavily on the export of resources like cacao, bananas, and oil to support their economy. However, the relationship between economic development and the environment most critically came into question in the 1980’s concerning mangrove deforestation due to shrimp farming. The influence of neoliberal policies that encouraged export-oriented development caused resource use conflicts and coastal management issues relating to mangroves and ancestral shrimp farming [1] [4]. Fundación Natura was the first environmental NGO to form in Ecuador in 1979, connecting activists and professionals who established environmental education programs focussing on natural resource management and conservation. Throughout the 1990’s, Fundación Natura’s influence grew and many other environmental groups were formed. Overall, the NGO's main objective was to work to connect regional networks together in an effort to “...bring national institutions in line with internationally established principles emphasizing sustainable development and the protection of biodiversity.” [1] (p. 947).

History of Indigenous Rights Movement in Ecuador

Paralleling the mobilization of the environmental movement, Indigenous rights activism was stepping into the spotlight at this time, with the demand for Ecuador to be recognized as a plurinational state at the forefront. Though more rooted in human rights, with fundamentally different goals from the environmental movement, the discussion of Indigenous rights does have an inherent connection to concerns about nature and resource management. An emphasis on “the intrinsic relationship between cultural identity and the mangrove ecosystem” [4] (p. 321) originated with grassroots organizations like Fundación de Defensa Ecológica (FUNDECOL), founded in 1989, and the NGO network Corporación Coordinadora Nacional para la Defensa del Ecosistema Manglar (C-CONDEM), created by FUNDECOL members in 1998. They worked to advocate for fishing communities affected by mangrove deforestation and facilitate the exchange of information among local organizations [4].

At a broader scale, despite there being many distinct and diverse Indigenous nationalities within Ecuador, the organizations often represent a general Indigenous cosmology in political discourse [1] (p. 950). For this movement, Indigenous Peoples of Ecuador were seeking “unity in diversity” -- to be defined politically alongside non-Indigenous peoples. This call for plurinacionalidad had a schematic connection between collective rights and the broadening of perspectives on subjects related to nature. Here, collective rights to ancestral territory, including land use and management were at the core of political struggles amongst Indigenous communities. For many, the land is relied on for sustenance and to maintain a connection to a cultural identity [1]. The central demands for plurinacionalidad were represented by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), an umbrella Indigenous organization. In the midst of the National Indigenous Uprising, at the Continental Conference of Indigenous Peoples 1990s led by CONAIE, it was stated that the “...land and indigenous peoples are inseparable. Land is life; it cannot be bought or sold. It is our responsibility to care for it according to tradition, to guarantee our future” [5] (p. 38) as cited in [1] (p. 948). Conclusively, the efforts of environmental NGOs and Indigenous rights organizations put pressure on the government to critically assess the current development model and its relationship with the environment.

Introduction of Rights of Nature (RoN) in Politics

President Rafael Correa (the first Indigenous president in Ecuador [6] (p. 708)) was elected to office in 2006 and formed a political coalition, Alianza País. Alianza País represented a progressive platform that criticized neoliberal policies, and promised to redirect Ecuador away from the traditional model of development that is based on an anthropocentric paradigm [7]. Correa proposed to rewrite the Constitution to acknowledge that nature, known as Pachamama in the Kichwa Indigenous language, has rights [8]. Correa also introduced the Kichwa term sumak kwasay, or buen vivir in Spanish, meaning, “good way of living”, to articulate the concept of recognizing the “interconnection of human, ecological, and cosmological realms of existence” [4] (p.318). Both environmental activist groups and Indigenous rights groups that had been placing pressure on the policy makers had interests that were represented in Correa’s political platform and his proposed constitutional reform. Upon his election, Correa called for a referendum to draft this new charter through a participatory process, electing 130 delegates to form the assembly that would receive and review constitutional proposals from throughout the country. Suggestions from citizens, private companies, environmentalist groups, and organizations representing Indigenous Peoples were accepted [1]. Critically, it is important to note the difference between a participatory vs. collaborative approach to developing policy. With a participatory method, executive power remains in the hands of an exclusive set of people. However, exhibiting transparency and allowing widespread public input was an immense improvement compared to the creation of the previous constitution, which was entirely constructed behind closed doors [1]. Overall, Correa’s rise to power was fed by momentum from social movements and the people of the public whose concerns aligned with those of environmentalist activists and Indigenous rights groups. As the product of a “citizen revolution” [9] as cited in [1] (p. 943), recognizing nature as a rights bearer was a revolutionary shift towards a non-anthropocentric approach to law [3].

Discussion: Case Study Vilcabamba River vs. Province of Loja

To investigate the merits of the “Rights of Nature” approach, as laid out in the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution, we will focus on one particular case study: Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011).

Case Overview

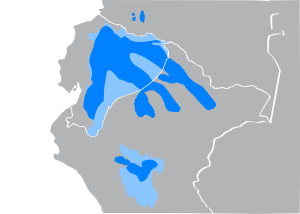

The Vilcabamba River is located in Vilcabamba, Ecuador in the Province of Loja. Prior to conducting risk assessments or land surveys (conducted by a reputable environmental agency -- in this case the Ministry of the Environment), a public contractor began a project to widen the Vilcabamba-Quinara road and this project went on for three years [10] (p.39). This case was introduced to the Provincial Court of Justice of Loja by international land-owners, Richard Frederick Wheeler and Eleanor Geer Huddle (Norie), who first noticed the construction during a trip to their “Garden of Paradise” on the banks of the river [11] (n.p). These property owners originally moved to the Vilcabamba River area in 2007 to create a “Garden of Paradise” -- a model for healing and sustainable living [12]. The main concerns of the road-widening project was the use of dynamite and heavy machinery in close proximity to the river, and the dumping of rocks and other construction materials into the Vilcabamba River. Not only does dumping damage the river bed, but it also results in an decreased river flow, excessive pollution, and floods, which put nearby river communities at risk [7] (p.7). One such flood occurred in 2010, covering about 3.7 acres of the most valuable agricultural land in the Uchima region and damaged 5,000 meters of Wheeler-Huddle land (US$43,000 worth of damage) [11] (n.p). To hear from Wheeler and Huddle visit: https://youtu.be/yVFTKsk5ZeI.

The case was first introduced to the Interim Judge of the Third Civil Court of Loja on December 15, 2010, but the case was denied due to a “lack of legitimacy” [11] (n.p). On March 30, 2011 the provincial court ruled that the Rights of Nature had been violated by the construction project and this was the first recognition of the Rights of Nature articles, as established in the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution. This ruling also recognized a “plaintiff’s right to sue on the basis of Article 71 of the Constitution, which establishes every citizen or nation’s right to demand the authorities the compliance with the rights of nature” [7] (p.7).

However, the ruling did not stop construction altogether. Instead the court ruled on a set of reparations and injunctions (Granted Constitutional Injunction 11121-2011-0010) to mediate existing environmental harm and prevent environmental destruction going forward. The reparations included [11] (n.p):

- The Provincial Government of Loja (PGL) has 30 days to present a remediation and rehabilitation plan to the populations affected by the dumping, and comply with recommendations of environmental authorities.

- PGL must present environmental permits to the Ministry of Environment.

- Implement corrective actions (e.g. clean soils, security bunds to prevent oil spills, storage for construction waste).

- PGL must comply with recommendations from the Sub Secretary of the Ministry of Environment.

- Create delegation: Regional Director of the Ministry of Environment and Office of the Ombudsman (from Loja, el Oro, and Zamora Chinchipe) to track the ruling.

- Public apology: ¼ of a page in a local newspaper.

Overall, Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011) was a landmark case in its application of the RoN articles in the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution and it provided a framework to learn from the successes and failures of the case in order to replicate these efforts on a wider scale.

Legal Bundle of Rights, Statutory Law, and FPIC

The case of Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011) and the RoN articles in the Constitution are examples of rights-based conservation practices -- the integration of “rights norms, standards, and principles into policy, planning, implementation, and outcomes assessment to help ensure that conservation practice respects rights in all cases and supports their further realization where possible” [13] (p.1). The inclusion of the Rights of Nature in the Ecuadorian Constitution, as mentioned previously, was done through a participatory approach where community members were actively involved in negotiating and creating the articles. In the Ecuadorian Constitution, all of nature is defined in the law, and the rights granted to nature (Pachamama - Mother Earth) are “to exist and maintain ecosystem integrity” and to be restored when damaged [14] (p.45). The RoN articles hold the maximum legal standing as a part of the Constitution and are described as statutory rights (written law). This is in contrast to customary law, which is not written into formal law, but instead are rights that are recognized by groups of people, specifically in connection with territory and resource rights. In all, everyone can represent nature, but one key piece that is not included in the Constitution is that there is no mandated, or required, responsibility to protect Pachamama. The RoN approach grants personhood to nature and within the legal bundle of rights, RoN provides the right to management, or in other words to regulate the internal use patterns of an area, in this case the Vilcabamba River.

Further, in the specific case Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011), one could argue that the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) was neglected [15]. FPIC acknowledges that Indigenous communities in the surrounding area, and if considering the status of the river as a person, the Vilcabamba River (through claimants on its behalf) have the right to be involved in decisions that affect the community or land. Free (F) implies that consent is given voluntarily, prior (P) means that consent must be provided well before the start of the project, and informed (I) means that all relevant information needs to be provided and examined before the start of the project and throughout. As mentioned, there was no scientific assessment completed prior to the start of the road-widening project.

Institutional/Administrative Arrangements: Discussion of Legal Pathways

As mentioned above, President Rafael Correa was elected into office in 2006 and was responsible for acknowledging the Rights of Nature in the Ecuadorian Constitution. Additionally, the Ministerio del Ambiente y Agua, or the Ministry of Environment and Water in Ecuador is another pertinent authority. The goal of this ministry is to “Exercise effectively and efficiently the leadership of environmental management" and their institutional values are integrity, vocation of service, responsibility, honesty, and respect [16] (n.p). This ministry is involved in overseeing environmental projects, permits, and plays a role at Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings. This case was also sent to the State Attorney General and the National Secretariat of Water. It is important to note here that in 2018, the Secretariat of Water was merged with the Ministry of Environment, creating the Ministry of Environment and Water. The “Ministry of the Environment” will be used in this review to describe the institution in place at the time of the case. The institutions directly involved with this case were the Ministry of Environment, Provincial Government of Loja, and the Ombudsman’s Office [17] (p.4). The role of an Ombudsman is to address the complaints of the public who have been treated unfairly by public authorities, including local authorities, government departments, and public hospitals [18] (n.p.).

There are four common pathways that RoN cases can take (i.e. civil, constitutional, criminal, or administrative action [see [19] for more information] ); however, in the specific case of Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja, norm-driven civil society pressure was utilized. Civil society pressure involves lawsuits presented by groups of individuals, or organizations (including NGOs) that put pressure on governments to uphold RoN [19] (p.9). Cases, such as this one can also be conducted using policy-driven government actions or professional interpretation by judges. The professional interpretation pathway includes cases that don’t explicitly relate to RoN, but cases in which the judge concludes that RoN can be applied during sentencing. Since this pathway involves the individual judge’s understanding of RoN in the Constitution, it is possible or likely that misinterpretation of RoN can occur, as was seen in the first hearing in the Third Civil Court of Loja [19] (p. 16).

For a full list of the 13 RoN cases in Ecuador up to 2016, view: [19] (p.6-8).

Key Stakeholders

Affected Stakeholders

In addition to Richard Frederick Wheeler and Eleanor Geer Huddle (Norie), the main affected stakeholders include the Vilcabamba River (as a rightsholder), the Province of Loja, and Carlos Eduardo Bravo González (plaintiff lawyer). At the local level, this case was brought to the Provincial Court of Justice of Loja. The main objectives of Wheeler, Huddle, and Carlos Eduardo Bravo González were to defend the Vilcabamba River’s rights against the destructive construction disposal methods of the road-widening contractors.

It is important to note the difference between rightsholders and stakeholders. An affected stakeholder is a person, group, or entity that has an emotional or cultural connection to the area, and whose long-term welfare is dependent on activities in that area. An interested stakeholder (as described in the following section), is one who is linked to the area in question and has a vested interest in it, but whose welfare is not dependent on it. In contrast, a rightsholder is an Indigenous person or group that holds ancestral linkages to their territory. In this case, the Vilcabamba River is granted personhood and is the rightsholder. Under RoN law, community members, Indigenous communities, or other people can come forward as claimants on behalf of nature to address any violations of RoN.

The people of Loja and the surrounding areas also hold stake in this case, and one Indigenous community that is in close proximity to this area is the Saraguro community (part of the Kichwa language group) [20]. The valley where the Vilcabamba River is located is known throughout the world as a sacred place (vilca = sacred, bamba = valley) with immense biological diversity [10] (p.38). The valley is called the “Valley of Longevity'' due to the long lifespan of inhabitants, although some researchers debate these claims [21] [22]. As a result of this distinction, newcomers from around the world have made the decision to retire in this area -- changing the local landscape and creating a divergence in cultural values and worldviews.

Additional provincial members involved in this case include Dr. Luis Sempértegui Valdivieso, Provincial Judge, Dr. Galo Arrobo Rodas, Interim Provincial Judge, and Dr. Galo Celi Astudillo, Associate Judge, as well as Dr. Dirce Guzmán Ordoñez, the Secretary of the Criminal Division of Loja [11] (n.p).

Government authorities typically have a high level of influence, given their position, while local communities and claimants, have a high level of importance, but not as much influence. Hence the need for outside NGOs and other groups to use their platforms to advocate for claimants.

Interested Stakeholders

Three pertinent organizations that are interested stakeholders in this case are the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, the Ecuadorian Coordinator of Organizations for the Defense of Nature and the Environment (CEDENMA), and Fundación Pachamama.

Firstly, the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN or the “Alliance”) is a global network of organizations, Indigenous groups, politicians, students, and more, committed to the universal adoption and implementation of the Rights of Nature [23] (n.p). GARN is the founder and secretariat for the International Rights of Nature Tribunal. The main relevant objective of this network, in the context of this specific case, is to uphold RoN as written in the Ecuadorian Constitution and ensure that the rights of the Vilcabamba River are respected. Given the global nature of this network and the number of NGOs and other institutions that are members of this network, GARN can be seen as a relatively influential stakeholder.

Secondly, CEDENMA is a private law, non-profit organization whose mission is to represent the collective interests of Ecuadorian NGOs, whose goals are to conserve nature, protect the environment, and promote sustainable development [24] (n.p.). Similar to GARN, CEDENMA’s main relevant objective is to defend nature from motives and actions that threaten the environment, and sponsor legal actions related to RoN. CEDENMA is a member of GARN, and is specific to Ecuadorian institutions; thus, it holds power within Ecuador itself as a private law organization with knowledge of the structures of the Ecuadorian government, at both the local and state-level.

The last organization involved was Fundación Pachamama, which is part of the core assembly of CEDENMA. Fundación Pachamama is a local-level organization (in comparison to GARN and CEDENMA), with the core objective of advocating with Indigenous communities, specifically Shuar, Achuar, Sápara, Shiwiar, and Kichwa territories of the Amazon rainforest. Fundación Pachamama, located in Quito, Ecuador, is a sister organization to Pachamama Alliance (a global network to promote a sustainable world). One key guiding value of this organization is: “Indigenous people are the source of a worldview and cosmology that can provide powerful guidance and teachings for achieving our vision—a thriving, just and sustainable world” [25] (n.p).

All three of these organizations are interested stakeholders, meaning these organizations are not directly located within the community, but play an important role in supporting Indigenous issues and Indigenous Peoples in national and international forums. Interested stakeholders can have a high level of influence and can mobilize resources and efforts to a greater degree than local communities.

Assessment of Governance:

While President Rafael Correa’s election was a large part of the success of the inclusion of RoN in the Ecuadorian Constitution (see "Introduction of Rights of Nature (RoN) in Politics"), there has also been counteractive legislation passed that casts a negative light on the administration. For example, after RoN was enacted in the Constitution, President Correa immediately launched a public campaign to pass a mining law that would expand existing operations and open new sites for mining [19] (p.4). Correa argued that the State “could ensure socially and environmentally responsible mining practices” and that profits from mining and oil extraction “were necessary to develop a post-fossil fuel energy sector, reduce poverty, and expand access to education, healthcare, and other public goods” [19] (p.4). Thus, no effort was made to create secondary RoN laws and regulations to expand buen vivir into other aspects of the government. This Mining Law (2009) ignited protests across Ecuador and the government shutdown organizations that were leading the charge, including the Development Council of Indigenous Nationalities and Peoples of Ecuador and Acción Ecológica (NGO’s status was reinstated in 2017) [19] (p. 4). In addition, Correa halted the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, blaming the global community for its failure. This initiative was designed to prevent oil extraction in the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) section of Yasuní National Park, in exchange for payments from the world's developed countries that matched ~50% of the value of the oil reserves (~$3.6 billion) [26] (p.59). While the Global North was complicit, Correa was also to blame for the failure of the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, and many started to question his commitment to environmental governance. In all, while the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution was a historic step towards incorporating ecocentric world-views at the government-level, it is important to recognize the conflicting interests and actions that are occurring in tandem with environmental progress.

Successes of the Case

As mentioned previously, Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011) is the first successful case in Ecuador where the constitutional rights of nature were implemented -- a momentous step forward in the international push for Rights of Nature legislation. The success of this case can be attributed to a number of factors. Firstly, the judge presiding over the case was friends with the claimants’ lawyer, and educated the judge on how to interpret the RoN provisions in the Ecuadorian Constitution. Additionally, the “judge’s ability to focus on interpreting the law correctly was no doubt helped by the fact that the case involved a mundane issue like provincial road construction, and not a nationally politicized issue like mining” [19] (p.13). Further, the RoN articles in the Ecuadorian Constitution have a greater scope and strength than many other examples (e.g. Pennsylvania, USA & New Zealand), as described in [14].

Failures of the Case

Specific to this case, the verdict did not necessarily stop construction, but instead set a list of tasks for the construction company to complete in order to continue the road expansion project. According to Cobo (2012), one year after the ‘sentence’ was issued, implementation was still lacking [27]. The PGL was ordered to present studies on the environmental impact of the project and craft rehabilitation plans for the Vilcabamba River, but those were never provided. In 2012, Fundación Pachamama, Huddle, and Wheeler, executed a judicial inspection and found that the only act of compliance undertaken by the contractor was putting up signs and doing a “superficial cleaning” of the river [27] (n.p). Fundación Pachamama has demanded that the Constitutional Court, the highest jurisdictional body in Ecuador, and Loja’s Ombudsman push for compliance. Thus, to answer the question -- is this verdict enough?--- the verdict itself was not enough, and despite the list of tasks, in order to show true respect for the rights of the Vilcabamba River it would have likely been more effective to halt the construction.

More broadly, while the case was successful, it does bring into question whether this success can be replicated, especially with more politically charged issues. With more complicated cases, including mining (e.g. Condor-Mirador Mining Project case 2013), the focus is generally put on navigating the political and economic environment rather than addressing the civil society’s concerns. As mentioned previously, oil extraction is a large part of the Ecuadorian economy, and has resulted in socioeconomic advancement, but also environmental degradation and community health issues. Since oil extraction is well ingrained in the Ecuadorian economy, it creates a conflict between RoN cases and economic advancement. Moreover, lawyers and judges often lack a full understanding of RoN articles and have difficulty interpreting them [19](p. 9). The conflicting rights of different interested and affected stakeholders and rightsholders, such as the Rights of Nature and the rights of development create a complex environment for the enforcement of RoN going forward.

Critical Assessment of RoN

Here, it is important to note that recognizing Rights of Nature does not make Ecuador's Constitution entirely ecocentric -- it still contains both ecocentric and anthropocentric values. It is also important to note that while Indigenous Peoples have rights-based interests in land management, it is problematic to assume that Indigenous Peoples are empowered by being environmental stewards and that their philosophies can be equated to ecocentrism. Tănăsescu (2020) critically evaluates the opinion that RoN is entirely ecocentric, and that ecocentric ideals are equivalently Indigenous ideals [28]. Tănăsescu argues that “...Indigenous philosophies are relational, being able to encompass both intrinsic values and instrumental uses, through the wide deployment of anthropomorphism" and that overall, ‘nature’ in rights language is defined too broadly [28] (p. 437). Moreover, Tănăsescu acknowledges that recognizing the Rights of Nature in the Constitution does not mean that Indigenous People’s demands for rights are met. In fact, RoN was not a key goal for Indigenous rights groups --- “The support that CONAIE lent within the Constitutional Assembly went much further than rights of nature and was centered on a package of rights that would strengthen Indigenous authority more broadly” [28] (p. 435). Legally recognizing RoN suggests that Indigenous values and demands for collective rights are merely being considered. Specifically, the failures of the Vilcabamba River case warrant criticism of the effectiveness of RoN in practice, and raises the question of if this successful outcome could be replicated. In addition, this case brings into question: if Pachamama includes humans, does respecting RoN violate the human right to development [10][7]?

Despite these valid points, it is undeniable that recognizing RoN signifies a revolutionary shift in the lens through which Western society views the world. Ecuador's initiative to give legal rights to nature supports RoN becoming a normative concept at the international level. Including other world-views leads to a validation and understanding of Indigenous struggles, and consequently more legitimate and accurate solutions to expand human rights using a post-colonial approach. Though Rights of Nature were not at the forefront of demands for the Indigenous rights movement, there is an inherent association between Indigenous rights (human rights) and the development models used to manage the land they are connected to. Making nature the subject of rights opposes the neoliberal development models that influenced Ecuador’s economy in the decades before, and offers a tangible method to reduce environmental degradation and protect Indigenous territory. This supports the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples (self-determination, rights to ancestral territory, and others outlined in The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UNDRIP) and represents an attempt to decolonize law [3]. Despite its flaws, the Vilcabamba River case is a monumental success in the practical implementation of RoN and as an exercise of human rights, this win is a step towards decolonizing international law.

Conclusion and Recommendations:

Overall, Correa’s push for constitutional reform to recognize the rights of Pachamama challenges the legal system on which capitalism is based and illustrates a shift to a more ecocentric paradigm [6] (p.719). At the foundation of this shift in paradigm is the influence of Indigenous knowledge on the fundamental concept of RoN, where “...The environmental aspect of this proposal is connected with the understanding that Nature itself is a subject, concurrent with the heterogeneous indigenous world-views present in the Andean region” [10] (p.37).

Specific to Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011), while Wheeler and Huddle are examples of international “newcomers” to the area, their efforts to uphold RoN in Loja and their power to win the case (with the help of various organizations) are indicative of a merging of world-views that could lead to increased success in RoN cases going forward. Here, the consideration of Indigenous world-views in law means that the original colonist legal discourse is beginning to accept and integrate alternative perspectives on nature. This legal recognition serves to validate and legitimize Indigenous philosophies, and their struggles related to colonization [3]. The support of Wheeler and Huddle as “newcomers” in this case exemplifies the acceptance and expansion of Indigenous world-views. In all, the practical implementation of RoN provides an avenue for the justice of historically oppressed indigenous groups [3].

Moving forward, our recommendations include incorporating the four R’s as outlined by Kirkness & Barnhardt (1991) on an international scale [29]. The four R’s include respect, relevance, reciprocity and responsibility. Kirkness and Barnhardt used the context of university campuses when discussing the four R’s, however, the same concepts still apply. In 2008, Indigenous and environmental activists criticized a law President Correa wanted to pass, prior to RoN, that would violate the rights of Indigenous communities by expanding mining sites [19] (p. 4). He responded by calling them “childish environmentalists” and “nobodies” [30] (p. 22). Increasing knowledge about Indigenous cultural values and traditions, as well as reducing the cultural distance between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people will lead to a growing respect for Indigenous communities [29] (p. 7-8). Reciprocity is explained by cross-cultural learning and teaching for all citizens in the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities [29] (p. 10). Kauffman and Martin identify three pathways for implementing RoN in Ecuador: civil-society pressure, government action and judicial interpretation [19] (p. 9). Because there are different measures and motivation from different actors, there is reciprocity in their actions. For example, the Ministry of the Environment uses RoN to justify administrative actions for environmental protection [19] (p. 15). As previously mentioned, there is a question of the success of RoN for more politically charged issues such as the Condor-Mirador Mining Project. For situations that are complicated like this, it is critical to enact responsibility. Responsibility is defined by Kirkness and Barnhardt as Indigenous Peoples having increased access to power, authority, and opportunity to govern everyday affairs [29] (p. 11). This would create less bias in policy making and result in a more balanced outlook on issues, such as an examination of socio-economic impacts, and environmental and health concerns. Further, relationality, or the concept that non-human kin have agency and equal rights, is vital to consider when negotiating RoN. In order to increase success, we recommend clarifying definitions of territories and boundaries, specifically the term ‘nature’, in existing and future RoN law (based on the critique of Tănăsescu, 2020 [28]). Lastly, given the concern of a lack of understanding for RoN law, or that politically charged topics might yield different results than Vilcabamba River vs. the Province of Loja (2011), we recommend the creation of a body or court whose purpose is to oversee cases relating to RoN. This will eliminate knowledge barriers and theoretically allow for unbiased participation at the legal level.

Endnotes

- The Ecuadorian constitution (2008) includes four key components related to the “rights of nature” approach (Georgetown University Political Database of the Americas 2011, n.p.):

- Article 71: “Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes. All persons, communities, peoples, and nations can call upon public authorities to enforce the rights of nature. To enforce and interpret these rights, the principles set forth in the Constitution.”

- Article 72: “Nature has the right to be restored. This restoration shall be apart from the obligation of the State and natural persons or legal entities to compensate individuals and communities that depend on affected natural systems.”

- Article 73: “The State shall apply preventive and restrictive measures on activities that might lead to the extinction of species, the destruction of ecosystems and the permanent alteration of natural cycles. The introduction of organisms and organic and inorganic material that might definitively alter the nation’s genetic assets is forbidden."

- Article 74: “Persons, communities, peoples, and nations shall have the right to benefit from the environment and the natural wealth enabling them to enjoy the good way of living. Environmental services shall not be subject to appropriation; their production, delivery, use and development shall be regulated by the State.”

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Akchurin, M. (2015). Constructing the rights of nature: Constitutional reform, mobilization, and environmental protection in Ecuador. Law and Social Inquiry, 40(4), 937-968 https://doi.org/10.1111/Isi.12141

- ↑ Borras, Susana. (2016.) New transitions from human rights to the environment to the rights of nature. Transnational Environmental Law 5(1): 113-143.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Guzmán, J. J. (2019). Decolonizing law and expanding human rights: Indigenous conceptions and the rights of nature in Ecuador. Deusto Journal of Human Rights, (4), 59-86. https://doi.org/10.18543/djhr-4-2019pp59-86

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Beitl, C. M. (2016). The changing legal and institutional context for recognizing nature's rights in Ecuador: Mangroves, fisheries, farmed shrimp, and coastal management since 1980. Journal of International Wildlife Law and Policy, 19(4), 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880292.2016.1248688

- ↑ CONAIE, CONFENIAE, SAIIC, ECUARUNARI, and ONIC. 1990. Declaración de Quito y Resolución del Encuentro Continental de Pueblos Indígenas. Pamphlet. Quito, Ecuador: CONAIE, CONFENIAE, SAIIC, ECUARUNARI, and ONIC

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Knauß, S. (2018). Conceptualizing human stewardship in the anthropocene: The rights of nature in Ecuador, New Zealand and India. Journal of Agriculture & Environmental Ethics, 31(6), 703-722 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9731-x

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Cano Pecharroman, L. (2018). Rights of nature: Rivers that can stand in court. Resources (Basel), 7(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7010013

- ↑ Berros, María Valeria. “The Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador: Pachamama Has Rights.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2015), no. 11. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7131.

- ↑ Alianza País. (2006) Plan de Gobierno del Movimiento PAÍS 2007-2011. Quito, Ecuador: Alianza País.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Berros, M. V. (2017). Defending rivers: Vilcabamba in the south of Ecuador. RCC Perspectives, (6), 37-44.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Greene, Natalia. (2011). The first successful case of the rights of nature implementation in Ecuador. Retrieved February 14, 2021 from https://therightsofnature.org/first-ron-case-ecuador/

- ↑ Garden of Paradise (n.d.). About Us. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from http://www.gardenofparadise.net/The_Garden_of_Paradise.html

- ↑ Campese, J. & Sunderland, Terry & Grieber, T. & Oviedo, G.. (2009). Rights Based Approaches: Exploring Issues and Opportunities for Conservation. 10.13140/2.1.4830.9445.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kauffman, C. M., & Martin, P. L. (2018). Constructing rights of nature norms in the US, Ecuador, and New Zealand. Global Environmental Politics, 18(4), 43-62. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00481

- ↑ United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (2013). Free, Prior and Informed Consent of Indigenous Peoples. [PDF file]. Accessed April 11, 2021.

- ↑ Ministerio del Ambiente y Agua (n.d.). The Ministry. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/el-ministerio/

- ↑ Suárez, S. (2013). Defending nature: Challenges and obstacles in defending the rights of nature Case Study of the Vilcabamba River. 14.

- ↑ The Office of the Ombudsman (n.d.). What we do. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.ombudsman.ie/about-us/what-we-do/

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 Kauffman, C. M., & Martin, P. L. (2016). Testing Ecuador’s rights of nature: Why some lawsuits succeed and others fail. Retrieved February 14, 2021 from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55914fd1e4b01fb0b851a814/t/5748568c8259b5e5a34ae6bf/1464358541319/Kauffman++Martin+16+Testing+Ecuadors+RoN+Laws.pdf

- ↑ Radcliffe, S., Laurie, N., & Andolina, R. (2002) Reterritorialised Space and Ethnic Political Participation: Indigenous Municipalities in Ecuador, Space and Polity,6:3, 289-305 DOI: 10.1080/1356257022000031986

- ↑ Mazess, Richard B., and Sylvia H. Forman. (1979). Longevity and Age Exaggeration in Vilcabamba, Ecuador. Journal of Gerontology 34 (1): 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/34.1.94.

- ↑ Mazess, R., & Mathisen, R. (1982). Lack of Unusual Longevity in Vilcabamba, Ecuador. Human Biology, 54(3), 517-524. Retrieved April 13, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41463395

- ↑ Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (2019, May 02). About Us. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.therightsofnature.org/get-to-know-us/

- ↑ Ecuadorian Coordinator of Organizations for the Defense of Nature and the Environment (CEDENMA) (2019, December 20). Quienes Somos. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.cedenma.org/quienes-somos/

- ↑ Pachamama Alliance (n.d.). Mission & Vision. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www.pachamama.org/about/mission

- ↑ Chimienti, A., & Matthes, S. (2013). Ecuador: Extractivism for the twenty-first century? NACLA Report on the Americas, 46(4), 59–62.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Cobo, Gabriela. (2012). Vilcabamba River Case Law: 1 Year After. Retrieved April 10th, 2021 from https://www.therightsofnature.org/vilcabamba-river-1-year-after/

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Tănăsescu, M. (2020). Rights of Nature, Legal Personality, and Indigenous Philosophies. Transnational Environmental Law, 9(3), 429-453. doi:10.1017/S2047102520000217

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Kirkness, V. J., & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and higher education: The four R's respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education,30(3), 1-15.

- ↑ Dosh, P., & Kligerman, N. (2009). Correa vs. social movements: Showdown in ecuador. NACLA Report on the Americas (1993), 42(5), 2 https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2009.11725465