Course:CONS370/Projects/Situating the current state of wildfires in British Columbia within the impacts of settler-colonialism on Secwépemc forest knowledge systems and management practises

This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS370. | |

This wiki takes an overview of the Secwépemc Peoples and their forest management practises, to conceptualize how the impacts of settler-colonial pasture-making, ranching, farming and logging have rendered the Southern Plateau of Interior ‘British Columbia’- Traditional, Ancestral, Stolen and unceded terrritories of the Secwépemc Nation- vulnerable to natural disasters. The following segments will first locate Forest practises and colonial tactics to uncover the fire-suppression policy. The paradoxical uses of Western and Indigenous fire, and the restrictions against who, where, when and how fires occur have resulted in ill-managed and susceptible forests. The future of healthy forest rests in returning land and forest tenure to Indigenous communities to begin re-instating Traditional forest practises and controlled burning as a means to mitigate the impacts of wildfires on the land and people alike.

The Secwépemc: Land Stewards for millennia

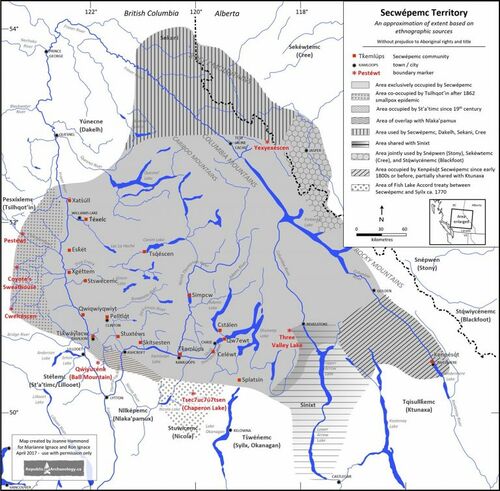

The Secwépemc Nation is located in the South Central Interior Plateau region of unceded territory in ‘British Columbia’, Canada. The territory expands roughly 180,000 sq km; The name Secwépemc itself translates to ‘the spread out people’ and is home to a range of communities who have inhabited this area for millennia. The Secwépemc people understand themselves to be stewards and protectors of the land and all of its life. Their complex spiritual belief systems guide their actions and governance toward their non-human relations. Secwépemc sense of place and self is deeply connected to their territories, and conceptions of time and space differ from European rigid, linear, and possessive world views. Pre-European contact, the Secwépemc had complex land mapping systems through storytelling; Many communities share stories that communicate the spirit of trees, fauna and flora found at various elevations. As the characters in the story move through their lands, they encounter the lives of other specific trees, animals and plants. The story will often provide nearby places of food collection or processing, nearby Bands or communities as a means of communicating the knowledge of the land with spiritual aid and agency. Secwépemc notions of kinship extend beyond their human relations, and into the world around them. Understanding all lives as valuable and equal allowed the Secwépemc to develop, over thousands of years, hunting, foraging, fishing and land maintenance practises that simultaneously provided for humans, and hope to promote healthy and successful growth of non-human lifestyles. Although language dialects, vocabularies and community dynamics may vary between communities, the Secwépemc share a deep connection to all life that share the land with them. The ideas of treating all lives equally and acts with reverence towards the land provides Secwépemc with tools of reciprocity towards forest and land engagement, harvesting, and management processes, ensuring a healthy web of life ensures the security of food, safety and shelter for the humans.

Secwépemc subsistence and diet is heavily connected to the forest, and they rely on the hunting, fishing and harvesting of wild animals and plants for a well-balanced traditional diet. The Secwépemc peoples have an intimate relationship with the forest and are able to identify over 200 edible plant and root vegetables in their areas that are used in meals or carry cultural significance (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). Many foraged forest foods used in meals, feasts, ceremony, preserved have medicinal purposes, or have broad utility as tools, clothing, hunting and fishing implements and shelter building (Ignace & Ignace,2017). The reciprocal nature of Secwépemc relationship with the land results in management practises that support and promote healthy growth and expansion of plants without causing damage, ensuring a larger yield for the next season's harvest. Where practices such as pruning, weeding, and transplanting are seen, we see the most common and effective forest management practices were controlled and prescribed burning(Hoffman, 2018; Trauernaught, 2015; Blackstock, 2004; Kimmerer, 2001; Ignace & Ignace, 2017; Turner, 1999). Throughout all practises was a commonality of reverence and respect for the land, it’s life, and a recognition of the gift of life that is given in order for the Secwépemc to sustain themselves. Their forest management practises and Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Wisdom (TEKW) are rooted in Kirkness and Barhart’s ‘the Four R’s’; Reverence, Respect, Reciprocity, Responsibility (2001) and work to build a mutually beneficial and supportive relationship with the plant and animal life. Crown settlement and governance beginning in the 19th century have separated and divided the Secwépemc nation into 17 bands, who still recognize their kinship relations, shared knowledge and histories. The histories of colonialism that have resulted in the the diminishing of Secwepemc practises and prevalence on the land will be considered in the next portion to understand how fire, specifically, was a target from colonial policy and settlement.

Colonialism and its Impacts on Secwepemc Forest Management

The arrival of the Europeans in the late 1900’s resulted in the dispossession and decimation of Secwépemc populations through disease such as measles, smallpox and tuberculosis for which their traditional healing methods had no solutions (Ignace & Ignace, 2017; Kelm 1999). The 19th century relationship with newcomers was one of Secwépemc control and sovereignty; Lost Europeans respected Secwépemc inherent rights and authority over land use and community practises, and learned may ways of working with the land through Secwépemc TEKW. The Westerners relied so heavily on Indigenous systems that the institution of the fur trade in the early 1800s traded goods from Secwépemc hunting, trapping, fishing and forest harvesting and established the fur economy. However, the relationship began to shift through the mid-1800s, when the fertility of the land was realized alongside the discovery of gold within their territory, bringing greedy settlers and farmers from the South.

Starting in 1858, with the Royal Proclamation claiming the Mainland as British soil and presented the opportunities of gold and fertile land, settlers pillaged communities in the pursuit of riches, and others began to pasturize. They would mass burn and plot areas that were previously expansive grasslands home to carefully maintained, biodiverse ecosystems of fauna, flora, elements-spirits-, and humans. The institution of private property facilitated pasture building and erected fencing which inherently impacted the ability for Secwépemc peoples to move through the land for harvesting and forest management practices (Blackstock, 2004). These spaces were previously cultural production sites where Secwépemc tended to the land, and executed routine controlled burning for hunting and foraging purposes (Blackstock, 2004). The State licensing of land to settlers resulted in overgrazed areas where tending and harvesting was no longer occurring, decreasing the quality of soil and impacting the variety and quantity of forage yields (Ignace & Ignace, 2017).

The influx of settlers resulted in further decimation of Secwépemc populations, and encroachment on more land, eventually leading to the reserve demarcation throughout the 1870s. The reserve demarcation process began with the signing of the Confederation in 1871, and separated and isolated Indigenous communities from their land, reduced access to customary territory and restricted movement. Supported by the signing of the Indian Act in 1876, the reserve demarcation process sought to clear land for incoming settlers and support assimilation of Indigenous communities to nuclear, sedentary agriculture-based lifestyles. Unfair and unjust allocation of land to small, infertile piece of land lead to an uprising and coalition from Secwepemc chiefs to communicate their concerns over land division and equity. Their response sparked governments actions to separate the Secwépemc reserves into distinct and autonomous bands and agencies to reduce their collective power as a nation. The process of creating 17 Bands throughout the unified nation impacted modern land tenure systems and makes for complex land recognitions and responsibilities through many different streams of governance (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). Beyond restricting Indigenous communities land boundaries and identities, the late 19th century brought devastating policy, and many settlers who control essentially all land up-to reserve borders, and demanding policy that provided “the best arable tracks of lands to be ‘cut-off’ from... reserves because the ‘Indians were not using them’” (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). Between 1880 and 1900, the Federal Government State officially implemented the Residential School Act, The Potlatch Ban, The Bush Fire Act and the Peasant Farming Policy, attacking the core foundations of Indigenous communities; The Children, and the Land.. These policies attacked and dismantled thousand-year systems of education, governance, food production, and forest management that embodied and continued the cultures and worldviews of the Secwépemc peoples.

The turn of the 20th century brought changes to Secwépemc territories and landscapes through more pro-settlement policy supporting the development of farms, ranches, pastures, miners and loggers. The 1890s ). In the early 1900s, gardening and small agriculture were beginning to be practises within Secwépemc communities and the rise of mixed economies; Partial wage work that made time for harvesting and hunting of wild foods and animals (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). The settlement occurring throughout the 20th century used a lot of prescribed burning-of a different nature- to clear expanses for agricultural use, scorching soils that were undergoing regeneration.

The intersection of reduced Secwépemc management processes with settlement resulting in land degradation, policies disrupting cultural transmission and cultural practises left degraded soils, and ill-managed, disaster-susceptible forests. The neoliberal dominance on ‘forest development’ and the economic benefits of logging stem from processes of land settlement, pasture building and resource extraction through 19th century colonialism.

Secwepemc uses of fire, pro-forest development policy against fire use through recent history

Pertaining specifically to the reciprocal maintenance of forest health and community nutrition, fire was used widely and often throughout Secwepemc territories to create fertile seedbeds, promote the growth of fire-dependant species, and clear out sun and nutrient competition. This section will explore the various uses, timelines and associations the Secwépemc have with fire and forest management through controlled burning. Situating and grounding the Secwépemc relationship with fire helps locate the ways in which settlement and pro-forestry policy have reduced preventative fire management with regular controlled burns and intimately maintained landscape practises and resulted in dry, overgrown and susceptible forests to natural disasters.

Secwépemc communities know of their fire uses through oral histories and collective memories. To support these claims in legible Western terms, evidence for Indigenous prescribed interval burning can be detected in “fossil charcoal, charcoal in aquatic sediments, charcoal layers in soil horizons, burned snags and stumps, fire scarred trees and distinct forest stand structures (Parminter, 1991). A study produced by Hoffman using LiDAR detections reveals that areas that underwent ritual prescribed burning grew taller, larger, and had a greater canopy spread than areas unattended to with fire (Hoffman, 2018). The plots of study also contained higher rates of biodiversity and pyrodiversity which supported higher abundances of plants and animals (Trauernicht, 1918).

Fire had a broad utility use: light, heat, cooking, hunt and drive, clearing trails, communication, visibility, ceremony, warfare. Most importantly, fire was controlled as “a crucial plant resource management technique among the Secwépemc and other Indigenous peoples of the Plateau and northwestern North America in general involved landscape burning to enhance the growth of berries and root plants, to control insects and invasive species like sage, to improve the forage for deer and elk, and to keep open meadows from growing over” (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). Burning hillsides of sagebrush and overgrown grasses is embedded into recent cultural memory, and the partnership elders made with fire to maintain the ‘well-kept, park-like appearance’ of the rolling hills in Secwépemc territories (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). Prescribed burning was not to be done at any time or place; Burning practises were “permeated with rules and rituals designed to ensure the collective health of the people...nature and all living things-including rocks, fire, water and other natural phenomena” (Bannister, 2000). Prescribed Burning events occurred in the late spring, when the grasslands were still damp and not susceptible to scorched earth. It occurred in interval cycles of 10-20 years, with variations based on type of plant targeted or their response to fire, giving the area time to regenerate with the increased nutrient stock and decreased competition. Burning was carefully executed under the guidance of an assigned resource steward, who was granted this position based on years of intimate relationship with the bush (Ignace & Ignace, 2017). Centuries of observing these practises resulted in identifying species that thrived with the support of fire and ash. Elder Mary Thomas of the Shuswap nation recounts in 1994 that “ our people deliberately burned a mountainside when it got so thick, nothing else would grow in it. They deliberately burned it, at a certain time of the year when they knew the rains were coming, they’d burn that, and two years, three years after the burn there’d be huckleberries galore and different Wa [edible] vegetations” (Turner, 1999). The practises of burning resulted in pyrodiverse and pyroresistent ecosystems during the dry season, and supported the quality and quantity of plant growth.

Bannister conceptualizes the uses of fire as Indigenous Peoples knowing and understanding- pre-Scientific enlightenment- the triangular interrelationship between humans, parasites and plant chemicals. The uses of burning fought off pests and parasites and ensured that the stock was healthy and undisturbed. The broad utility of many forest foods as medicines recognizes the human relationship with plant chemicals and blurs the lines between diet, physical activities, and health practises; promoting the growth of healthy environments, bodies and spirits (Bannister, 2000). Controlled burning in this sense was a manifestation of kinship beliefs, where humans had the capacity to control fire, and the responsibility to use it to promote the health of their relationships.

Western encroachment and privatization of land dismissed the vast range of benefits associated with prescribed burning, and negated its productive use. Westerners, instead, viewed fire as a source of destruction; Destroy what was there for pasture-making through burning, and the threat of fire to the rows of isolated and plowed crops survivability. They failed to recognize the uses of fire in deterring pests and increasing pyro resilience. The next section will cover the unfolding of Western policy making that rendered fire ‘a menace to Western society building’, geographically restricted fire management practises through fences and ‘no trespass’ signs, and legislatively prohibited the preventative mechanisms of Secwépemc prescribed burning.

Effects and Timing of Policy

The policies of fire suppression throughout the 19th and 20th century settlement processes generated a paradoxical effect; The presence of Western pasture techniques lead to major increase in landscape burning for the purposes of clearing and preparing large expanses of land. Simultaneous to this increase was the restrictive policies set in place around burning that protected people from any damage to ‘Crown Land’ or private property (Stolen Indigenous territory). At the same time as we see decreased prescribed, controlled and preventative burns, there is a major increase in uncontrolled, wildfires set by Western farmers. This simultaneous process occurring gradually over 200 years rendered the 21st century forest and hillside landscape dry, unattended too, and vulnerable to large-scale brush fires. The loss of ritual burning to be replaced with scorched surfaces has decreased the quality of soils in the area, and in turn the quality and quantity of forest food yields.

The 20th century influx in settlement and ranches resulted in over-grazing of grasslands, over-logging of forests, and non-regulatory timber removal without mandatory clean up of dry and combustible debris. The loss of forest control and tenure through the Royal Proclamation and the Confederation in 1871 resulted forest landscapes under the tenure of the British Crown and left unattended, and destructive land practise of settlers unexamined. The Land Act of 1884 allotted grants and licensing to new settlers and companies interested in building the logging industry. This process brought the commercialization of timber and agriculture, and the introduction of large companies and shifted the stakeholders in the area, increasing the inherent inequalities of access and control in the Western Settler-Colonial structure (Pearce, 1992). Big timber, mill and trading companies settled in the area and began logging without any required clean-up or protocol of effective logging practises; The pasture building fire practises combined with the increased removal of timber resulting in leftover, dry brush resulted in a series of wildfires in the region, and by 1917, 26 million hectares of forested areas had been destroyed by fire, and much remaining timber had been scorched (Parminter, 1991). In 1911, in the midst of a series of wildfires ignited by settlers, blamed Indigenous fire management practises for the repeated damage on Crown and Private land and legislated the Forest Forest Act. The act was developed by crown, land owner, licensees of forested land, and without the Secwépemc. It declared “any flammable material which endangers life or public property a public nuisance, and for the land owner/occupant to ‘remove or abate’ such substance” (Parminter, 1991). This legislation proved no impact on the wildfire outbreaks, and in 1923, the British Crown labeled fire as “a menace to the economic wellbeing of the British Empire and constitutes the single greatest deterrent of the practises of forest management” (Parminter, 1991). The English were at the time, unattentive to the various uses and benefits of fire, and with their ignorance, applied a double standard of judgement to the uses and effects of fire. While Indigenous Peoples were restricted physically and legally from practising burning throughout the 20th century, Western settlers faced no threat due to their claims on ‘private property’. The Secwépemc knew full and well the results of over grown brush-from surviving histories of Wildfire ignited by lightning, and carefully curated burning regimes to respond to and prevent these instances. Colonial policy making actually rendered the forest more vulnerable through over-logging, commercial building of agriculture and ranches, without the responsibility towards the land to ensure its health and resilience. The result of unregulated logging left dry brush and fuel around the forest floor, waiting to be ignited (Parminter, 1991). It wasn't until the 1970s that the government of British Columbia considered the ways in which burning could be used as a preventative tool and a means of increasing visibility and movement through a landscape.

The processes of settlement complicate the structures of tenure in British Columbia and grants, licenses and permits are handed out to massive timber companies regularly. Since the evolution and dependence of the timber industry in the area, coinciding with ignorant practises that do not incorporate slash burning, brush burning, or preventative fires, the turn of the century brought a massive increase in severity of Wildfires. Tree Farm License(TFL) 35 was put in place in 1959, and continues to be updated. it covers much of Secwépemc territory and facilitates logging in the area. It began with BC Interior Sawmills LTD. and is now registered under West Fraser Timber LTD. for the next 20 years (. The next section will explore the Structure of community and Indigenous Peoples inclusion in Forest licensing as a means to reclaim control over territory, timber industries and forest management practises.

Reclamation of forest management

The development of Secwépemc territories into urban and residential centres throughout the 20th and 21st centuries creates a complex system of forest control, split between the Crown, TFL 35, Farmers, Independent Forestry Companies, Community Forest Licensees, Limited Liability Companies(LLC), Forest Venture companies, and other timber-involved residents. Tree Farm License #35 still remains intact in the territories of the Secwépemc, as well as the operation of multiple saw and pulp mills. The histories of band and agency-making referenced earlier in the page results in a complex process of Indigenous tenure reclamation’s, where each band agency generates and signs their own agreements. To this extent, there is no consensus across Secwépemc territories on Forest and Timber management practises, but there are individual processes of land and tenure reclamation occurring across communities in the forms of LLC’s, Forestry Venture Companies, and Community Forests. The Secwépemc are also ensuring that their voices are heard in the evaluation of impacts and prevention tools for high impact Wildfires.

The 1998 Amendment to the Land Act, allowed Indigenous communities to retain long-term community forest licenses that permitted community care and long-term landscape planning (Shuswap Passion). In the Shuswap territory, there are 2 community forests: Monashee Community Forest, and Cherryville Community forest. Simultaneously, there are efforts such as Qwelminte Secwepemc collective, which driving a pivot to nation-wide forest control, and seek to establish on the ground spaces for Secwepemc Peoples to practise and control the forest management systems, and provide pathways to re-establishing management practises such as burning, pruning and transplanting. Community forests offer collaborative ways for communities to implement TEKW into their landscapes which have been restricted from their care for generations. These systems seek to broaden the scope of forest value beyond the financial output of timber, and recognize the multitude of ways to interact with, harvest and care for the forest in productive manners. The Tk’Emlups Forestry Company has been granted a long term tenure in order to provide access and control over Tk’Emlups forests, provide economic income and job opportunities for their communities. Opportunities of co-management with LLC licensing can provide the support of funding, equipment and training to communities who are in the early processes of land reclamation, but it often does not provide pathways to re-defining forest values and best practises. Meanwhile, the “Likely/ Xats’ull Community Forest (LXCF) Tenure is one of a few community-driven, joint-venture, forest tenure agreements between a non-First Nations and a First Nations community in British Columbia. The absence of the province or its licensees as a mediator in the relationship between the Village of Likely and Xats’ull First Nation has assisted in cultivating cross-cultural communication processes directly between the communities” (106). Within certain communities, there is many actions towards reclamation of land tenure and forest practises as a means to navigate the complex social and ecological landscape that has risen as a result of Colonial settlement and over-production of land. These actions seek to re-establish Secwépemc worldviews and practises that embody reverence, reciprocity, respect and responsibility towards the land and all of its life in the making of forest industries.

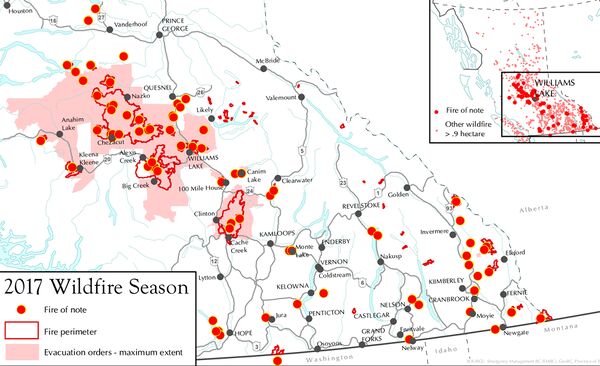

Looking back while Moving forward: Looking at the impacts of the 2017 wildfire season

In the face of one of the most destructive wildfire seasons in recent history, The BC Flood and Wildfire review published a reflection on the shortcomings of fire prevention and management techniques to imagine the creation of better systems. The 2017 wildfire season released an estimated 190 million tones of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere, burned more than 1.2 million hectares of forest, and displaced approximately 65,000 people (Chapman, 2018). This report concluded that the need for more “low-cost, landscape treatments (including prescribed burns) that can slow, divert or even halt large-scale wildfires” (Chapman, 2018, 8). The report carefully considers United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in advocating the need for Indigenous participation in forestry industries and fire management practises. To achieve low cost mitigation of fires will require “partnership with First Nations, [the incorporation] of greater traditional use of fire as Indigenous Peoples have been doing for millennia”(8). The report turned to conducted meetings with Chief and Councils, members of Secwépemc communities, and made presentations at the BC Wildfire Summit for advice and as a means to advocate for Indigenous principles and participation in Natural Resource Management. Don Ignace of the Skeetchestn Band advocates the need for more than an emergency preparedness plan, he believes “local/ Indigenous knowledge of the land is invaluable in thinking about planning for wildfires and other emergencies” (55). Secwépemc communities were majority in response for implementing cultural prescribed burning due to the perception that “prescribed burning would help reduce the risk of future wildfires” if it’s methods carefully considered the current landscape and conducted themselves within TEKW frameworks with reverence for the land. Secwépemc communities also advocated for changes in policy and economic considerations to diversity wood use, legislation of logging regulations, and shortcomings on government assembled Forest Stewardship Plans in maintaining a healthy landscape. The report offer 106 recommendations for improving forest management to further avoid damage from fire and flood, 56 of which mentioned the centring of and/or partnership with Indigenous communities in forest management plans and practise.

Recommendations

Providing granting and licenses to autonomous Indigenous Forest Management companies such as LXCF, and the possibility for them to extend their jurisdiction nation-wide to eventually assume full control over the area and its productions.

Returning access to forests and tenure over forest use and access as a means to re-generate Indigenous forest management practises in the scope of industrialized space and changing climates.

Developing culturally-informed programs and systems of fire use to re-invigorate the forest soil, provide means for future harvesting practises, and re-establish Secwépemc forest management practises, laws and forest values as the baseline for forest interactions.

Repairing and redefining the definitions of a ‘forest-ecosystem’ to include the influence water and other metaphysical elements and broaden the scope on the values of a forest beyond timer and Annual Allowable Cut.

Creating tangible timelines and practise locations to use prescribed burning as a mitigating factor to pests and potential wildfires in the summer, as a means to protect Indigenous communities, settled communities and the land alike.

References

Bannister, K. P. (2000). Chemistry rooted in cultural knowledge: Unearthing the links between antimicrobial properties and traditional knowledge in food and medicinal plant resources of the Secwépemc (shuswap) aboriginal nation

Blackstock, M. (2002). Water-based ecology: A first nations' proposal to repair the definition of a forest ecosystem.BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management, 2(1)

Blackstock, M., and Rhonda, M. "First Nations Perspectives on the Grasslands of the Interior of British Columbia." Journal of Ecological Anthropology, vol. 8, no. 1, 2004, pp. 24-46.

Chapman, M., Abbott, G. M., BC Flood and Wildfire Review, British Columbia, & British Columbia Government EBook Collection. (2018). Addressing the new normal: 21st century disaster management in British Columbia : Report and findings of the BC flood and wildfire review, an independent review examining the 2017 flood and wildfire seasons. BC Flood and Wildfire Review.

Government of British Columbia. 2021. TFL 35. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/forest-tenures/timber-harvesting-rights/tfl/tfl-35

Government of British Columbia. 2010. “Tree Farm License 35. Jamieson Creek Tree Farm License”.

Government of British Columbia. 2021. “Forest Consultation and Revenue Sharing Agreements”. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/consulting-with-first-nations/first-nations-negotiations/forest-consultation-and-revenue-sharing-agreements

Hoffman, K. M., Trant, A. J., Nijland, W., & Starzomski, B. M. (2018). Ecological legacies of fire detected using plot-level measurements and LiDAR in an old growth coastal temperate rainforest. Forest Ecology and Management, 424, 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.04.020

Ignace, M., Ignace, R. E., & Xwi7xwa Collection. (2017). Secwépemc people, land, and laws: Yerí7 re Stsq̓ey̓s-kucw. (Chapter 3, 5, and 12). McGill-Queen's University

Jules, J., Thomson, S., British Columbia Government EBook Collection, British Columbia. Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, & Tk'emlups te Secwepemc. (2013). Forest tenure opportunity agreement (the "agreement"): Between tk'emlups te secwepemc as represented by chief and council and her majesty the queen in right of the province of british columbia as represented by the minister of forests, lands, and natural resource operations ("british columbia") (collectively the "parties'). Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations.

Kelm, M., & desLibris - Books. (1998). Colonizing bodies: Aboriginal health and healing in british columbia, 1900-50. Chapter 1. UBC Press. 1-32.

Kimmerer, R. W., & Lake, F. K. (2001). The role of indigenous burning in land management. Journal of Forestry, 99(11), 36.

https://native-land.ca/

Parminter, J. (1991) “Burning Alternatives Panel: A Review of Fire Ecology, Fire History and Prescribed Burning in Southern British Columbia”. At Sixth Annual Fire Management Symposium. Kelowna, B.C.https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hre/pubs/docs/sifmc.pdf

Pearse, P.(1992). Evolution of the Forest Tenure System in British Columbia. Vancouver, BC.

Trauernicht, C., Brook, B. W., Murphy, B. P., Williamson, G. J., & Bowman, David M. J. S. (2015). Local and global pyrogeographic evidence that indigenous fire management creates pyrodiversity. Ecology and Evolution, 5(9), 1908-1918. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1494

Turner, Nancy. (1999). “‘Time to Burn’:Traditional Use of Fire to Enhance Resource Production by Aboriginal Peoples in British Columbia”. Indians, fire, and the land in the pacific northwest (1st ed.). Oregon State University Press.

https://shuswappassion.ca/economy/the-many-benefits-of-community-forests/

https://www.qwelminte.ca/forestry occurring to pivot towards nation-wide forest controls