Course:CONS370/Projects/An Overview of the Traditional Practices of the Ainu People of Japan and Their Relationship with Their Territory

The Ainu people are Indigenous Peoples whose territory falls in the islands now known as Japan[1]. This Wiki page is an overview of the history of the traditional practices of the Ainu people, highlighting how the relationship between the Ainu and their territory has changed throughout time. The impacts of colonization on these practices and relationships are also reviewed on this page, focusing on how assimilation has contributed to the erasure of Ainu identity and traditional practices. We have also included an overview of Ainu revitalization movements and rights advocacy, expressing the continued fight of the Ainu to continue their traditional practices and achieve self-determination.

| Theme: Community Forestry | |

| Country: Japan | |

This conservation resource was created by Atiyah Heydari, Veena Vinod, Sylvie Yang. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

Description

The population of the Ainu people is estimated to be around 28,000 people, although this statistic is difficult to determine because of Ainu hiding their identity to escape discrimination[1] and because of Japan's lack of a census based on ethnicity[2]. Like many other Indigenous communities, the Ainu have faced countless acts of violence perpetuated by the colonial government, from forced assimilation to the Japanese governments disregard of Ainu sovereignty and rights[3]. Despite the injustices the Japanese government has forced on them, the Ainu have continued their diverse cultural practices and remain resilient in the face of colonial violence.

Intra-cultural Variation

The Ainu are not only culturally different from the Japanese but also ethnically. It is believed that the Ainu originated from Mongoloid, Oceanic, or Caucasian races. It is also believed they may have originated by isolation from ten thousand years ago[4].

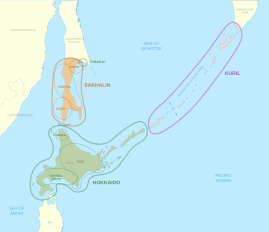

There is intra-cultural variation found between sexes, different social status, and age groups. However, there is also a high level of regional variation in Ainu culture[5]. The Ainu are split into three major regional groups: Hokkaido Ainu, Sakhalin Ainu and Kurile Ainu. However, the Ainu peoples found in southern Kuriles are usually included with the Hokkaido Ainu as their cultures show high levels of similarity. Regional differences of culture between the Ainu are also due to the social environments they have adapted to, depending on the groups of people they are surrounded by. Ainu living in southern Japan are surrounded by the Japanese, Ainu living in northern Kuriles are surrounded by the Kamchadals and Russians, and Ainu living in southern Sakhalin are surrounded by the Russians and Chinese[5].

Kurile Ainu

Kurile Ainu wear bird-feather garments, use semi-subterranean pit houses, and create pottery. They are the least sedentary among the different Ainu groups. Kurile Ainu have a heavy emphasis on fishing, hunting of marine birds, and hunting of sea mammals such as sea otters. They also use dogs to pull sleds and also use them as a food source[5].

Hokkaido Ainu

Hokkaido Ainu use metal goods traded from the Japanese and Chinese. They tend to have larger settlements that are usually permanent. They don’t use pit houses nor do they participate in seasonal migration. Hokkaido Ainu also kept domesticated dogs that were also sometimes used for hunting. When hunting, they would poison their arrowheads with aconite or stingray poison, as a hunting aid. Besides hunting, the Hokkaido Ainu also practiced plant cultivation[5].

Sakhalin Ainu

Sakhalin Ainu also use metal goods traded from the Chinese. Unlike the Hokkaido Ainu, they practice seasonal migration and use pit houses in the winter. The Sakhalin Ainu rely on fish, sea mammals, land mammals, and plants as their food sources. They used dogs for both castration and selective breeding. They produced fine basketry, woven mats, and clothing made from fur and fish skin. Shamanism held more importance with the Sakhalin Ainu than the Hokkaido Ainu[5].

Traditional Practices

Food Practices

The Ainu live in regions that have a cold climate, they learned to stick to hunting and gathering, while also learning to adapt to the local ecology. They also relied heavily on sea and land mammals such as fish, musk deer and reindeer. Long and severe winters forced many Ainu to practice seasonal migration. During the mid-winter the Ainu would literally be “snowed in” and so they would live on stored food[5].

The relationships between different generations and food traditions vary greatly between age groups due to the social changes in Ainu society. The Ainu Elders were raised with the knowledge of traditional foods that were passed on generationally[6]. Due to the oppressive State policies in place, the Elders were forced to give up aspects of the Ainu lifestyle. Furthermore, many Elders gave up and suppressed their Ainu lifestyle due to the fear of facing discrimination. One Elder quoted “I did not teach my children [the] Ainu language and Ainu way of life, because I thought they wouldn’t need it”. The Ainu culture was not openly celebrated[6]. Their traditional foods, a significant part of Ainu culture, was blended into Japanese culture. They avoided consuming foods like pukusa (wild onion) or cooking Ainu meals at home. This resulted in Ainus cooking more Japanese meals[6]. A negative association with Ainu food culture developed. Some Elders expressed that “they missed old food”. Others associate Ainu food culture with poverty and the negative experiences that were lived due to the policies implemented by the government. The regulations put in place in the Meiji era forced the Ainu to adopt rice farming and the domestication of animals. Other spices, ingredients, and seasoning such as miso, replaced traditional foods[6].

The generation that followed [insert dates], the middle aged Ainu, lived mainly as Japanese. This generation was the children of the Elders. Many of them were raised without the knowledge of the language and culture of the Ainu but were rather raised as though they were Japanese. Two main patterns could be observed with the relationships to food in this generation. The first pattern was the integration of Ainu foods into Japanese culture. Many wild vegetables and foods were incorporated into Japanese cuisine, although the Ainu names for the foods and ingredients were abandoned. With the foods now having Japanese names, this generation of Ainu were raised eating these foods without the knowledge that they were of the Ainu culture. The second pattern was that the Ainu foods were predominantly only being cooked and eaten for special occasions and ceremonies by the Elders[6].

Many traditional methods were not passed on to the younger generations such as the traditional methods of drying vegetables that were used by the Elders when freezers and refrigerators were introduced into homes. Hunting, gathering and fishing, which were practiced by the Elders, required traditional ecological knowledge and this was not passed on to the younger generation[6].

The Ainu traditions and culture was no longer actively being practiced. The youngest of the Ainu were raised with limited exposure to the Ainu lifestyle and traditions. Their knowledge was passed on predominantly from school and other events, rather than from Elders[6].

Traditional Dances

Traditionally, dances are performed for either entertainment or ceremonial purposes. Kamuy or Kamui means the divine beings that inhabit the earth. Many of the cultural dances performed by the Ainu are intended to replicate the movements of nature and to commune with these divine beings[7]. Many traditions have been passed on through artistic expression demonstrated through carvings, designs on mats/garments. Oral literature by scholars such as Kindaichi, Chiri, Yamamoto who wrote many beautiful poems also helped in passing on traditions to future generations[5].

Motifs

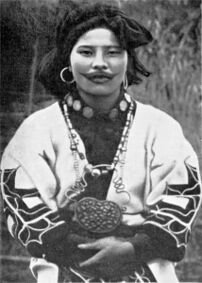

Although Ainu culture has been categorized as an oral culture, physical evidence of their history and culture exists in Ainu motifs, which act as social texts within their communities[8].

Kumay

Yukar is a practice of reciting oral literature that leads to improved relations with the spiritual beings known as kamuy. The kamuy play a role in regulating the subsistence economies of the Ainu and are indistinguishable from humans. Motifs are used to create patterns on their robes to differentiate the kamuy from humans[8].

Identity

Motifs on garments are significant to reinforcing the identity of both the kamuy and the Ainu. Motifs on garments known as Amip are created for the individual, a design that is unique to them and is not repeated on any another Amip. Ainu motifs act as "an expression of the soul," allowing an individual to present themselves to the kamuy in attempts to gain their attention and help protect against evil[8].

In the nineteenth-century, motifs on men's garments could also communicate different characteristics about themselves such as their status in society, financial standing, age, marital stats, residence, and spouses's skills[8].

Festivals

Bear Festival

The Bear Festival, also known as Iomante or Kamaokuri, means bear sendoff. This festival can also be called Kumamatsuri. The purpose of this festival is to spiritually release a captive bear's spirit. A bear is chosen as the sacrificial bear as a cub, it is then raised by the Ainu peoples, and then finally the bear is sacrificed. The sacrificed bear is considered a gift from Kim-un Kamuy, the god of bears. The sacrificial bear is used in many ways, such as for food. The bear's fur and bones are also used. It is believed the bear's spirit is able to depart for Kamuy Mosir, the land of the gods, because it had been sacrificed[7].

Kotan-nomi

Kotan-nomi is a modern recreation of a traditional Ainu ceremony. During this ceremony, the Ainu peoples pray for their home, their village and for overall good fortune. The Kotan-nomi festival is held at the Sapporo Pirka Kotan which is an Ainu cultural center, in June. During the ceremony you can find traditional music and watch a Circle Dance[7].

Tattoos

Tattoos hold cultural value for Ainu peoples, especially for women. Around the age of 10, Ainu women begin getting their tattoos on their face and hands. The tattoos are designed in a way that will allow them to become enlarged as the women age. Once the Ainu women reach the age of 16, the tattoos become a sign of marriageability[7].

Medicine

Ainu peoples do not have a medical specialist as it is expected that every adult should understand the basics of diagnosing and curing habitual illnesses[9]. This is important for the Ainu peoples as they may find themselves in tough situations, such as falling ill while by themselves in the mountains or collecting plants[9]. Despite this, women tend to be more knowledgeable on treatment of illnesses as they are usually the ones collecting the materials for healthcare such as plants and shellfish[9]. The women are taught to be able to identify the medicinal plants in the wild[9].

The opposite of illness, meaning one is healthy, is known as ramu pirka meaning “soul beautiful”.[9] The Ainu believe that one's soul needs to be in proper order for one's body to also remain in good condition[9]. This is why the Ainu believe in order to maintain good health, one must have high moral behaviour[9]. Furthermore, many cures for illnesses tend to be based on religion such as dreaming about specific deities in order to cure certain ailments[9].

Habitual Illness

Habitual Illness are also known as illnesses that have standardized diagnoses and cures. This can be aided with using medicinal plants and can be diagnosed on the basis of pain and the appearance of the ailing part of body[9]. The following is an example of a diagnosis and cure of a habitual illness: a person that experiences a headache that simulates the sound a dog gnawing on something hard is called seta sapa araka (meaning dog headache)[9]. It is treated by giving the patient a paste made from the powder of a grounded dog's skull. The practice of habitual diagnoses and treatment may be done by anyone, unlike supernatural illnesses which can only be done by a shaman (more on shamans in the “Supernatural Illnesses/Metaphysical Illnesses” section). Habitual illness can further be broken into 3 sub groups:

Body part illnesses- illness in this category are identified by the location of the ailment for a particular body part or internal organ. Illnesses in this category include headaches and infections[9].

Bone illness- also known as poni tasum araka meaning bone pain illnesses. This subgroup is identified as the pain that can be found in the bones and joints[9].

Skin abnormalities- this subgroup is quite large and includes cuts, bruises and burns that are caused by outside agents. However, these do not include all types of skin ailments such as skin injury sustained by a bear, which has a specific type of cure and is described below. This subgroup also includes boils, blisters, swellings and rashes[9].

Supernatural Illnesses/ Metaphysical Illnesses

Supernatural Illnesses are illnesses that involve the soul, a deity or demon. These can be found as either a pathogen, a curative power or in etiology. A shaman is needed in order to cure these types of illness[9].

When the Ainu peoples are facing more serious metaphysical illnesses, they must go see a shaman who is a part-time medical specialist. The Ainu call shamans tusu aynu (meaning shamanistic rite human being). This is because shamans are believed to have superior power than that of an ordinary Ainu person as shamans are thought to have properties of the Ainu deities[9]. They are consulted by the sick in order to receive diagnoses and curing methods. Shamans in the Ainu community help heal other Ainu by using their power from deities and also taking into account a person's thoughts/dreams before making a diagnosis. A future shaman will receive their “call” when they are a teen and start their career/training quite early (around the time of puberty)[9]. There is no outline of what a “call” may look like but it is described by some shamans as an uncontrollable desire to perform shamanistic rites. They are then allowed to perform their first shamanistic rite at their first life crisis while they are unconscious. It takes many years before one can become a fully fledged shaman[9].

Injuries Sustained by a Bear

Some specific types of injuries require specific and special types of treatment. An example of this is any type of injury sustained by a bear. When someone has a grave illness related to a bear attack, they are put into a hut made of tree bark called Kuča[9]. Then they are only allowed to be taken care of by postmenopausal women. This is because bears are very sacred to the Ainu so when someone has been injured by one, they are thought to also have become sacred, however menstrual blood is seen as a contaminant to this sacred being as they must remain uncontaminated[9]. Freshly cut firewood is also to be used in the hut as to avoid firewood that may have been possibly contaminated by animal urine[9].

Language

In 1993, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) listed the Ainu language as one of the many languages that are nearly extinct. At that time there was only tens of speakers and all of them were elderly. The decline of the Ainu language is due to centuries of discrimination, oppression, forced assimilation, and social/political control by the Japanese who are the majority ethnic group[4]. In 1996, according to the Atlas of World Languages in Danger of Disappearing, sponsored by UNESCO, there were roughly 100 native speakers and they mainly lived in Nibutani (northernmost island of Hokkaido). With the loss of their language, the Ainu also began to lose yukar. Yukar is the rich oral traditions which involved legends, morals, and epic hero tales. Yukar transverse generations because their language was unrelated to any other language. Today, the Ainu language is written in an altered version of Katakana which is Japanese syllabary[4].

Settlements

People were not tied to particular settlements. If one wishes to to leave a settlement, they are free to do so, with no formalities[5]. If someone came in conflict with another member of a settlement, they were able to just leave in order to avoid further conflict[5]. Settlements would often rely heavily on neighbouring settlements for many things. Firstly, they would rely on neighbouring settlements for basic items such as food[5]. Secondly, settlements would rely on other settlements to help with trials or other political matters[5].

Technology

Technological advances include basket weaving, forging for iron, dog domestication, and poisoned arrows[5]. The Ainu had a tendency to incorporate foreign elements and then reinterpret them with their own cultural patterns[5].

Modes of Production

Hunting and Gathering

Ainu predominantly focused on hunting and gathering to support their living. The tasks of providing the necessities of life were usually divided by gender. The males were predominantly tasked with hunting and fishing for land and sea mammals. Some important sources of food that were hunted by Ainu include deer and large fish such as salmon and trout. Women and children were responsible for gathering and foraging plants such as Leeks, berries and roots such as lily bulbs[10]. They were also in charge of preserving and storing the foods that were gathered and hunted.

Foraging and hunting were both done with great care to not damage the ecosystem. It was a selective and limited process. Several of the resources consumed by Ainu are available only seasonally or limited to specific locations. Therefore Ainu strategically prioritize when to gather or hunt specific species to ensure depletion of species does not occur. Very often, the locations of settlements were made with consideration of the ability to obtain resources, especially the availability of fish. This is evident as most Ainu settlements were near river banks or along shorelines. Some Ainu communities chose rather to migrate in accordance to the seasonal migration of the fish they depended on.

Fish was one of the most important sources of food and therefore their availability prompted mitigated settlement locations. For the winters, fish was usually preserved dried or smoked to last through the cold season when fishing was not as accessible[10]. The oils provided by fish were also utilized for fuel or for cooking The skin of fish was also used in the making of garments and shoes. Plants were gathered throughout the seasons and dried for use in the winter. It made up a significant part of the Ainu diet especially when fish or meats were not available. Many plants were also gathered and used for both medicinal and religious purposes Unlike fishing, the availability and location of plants did not heavily impact the location of settlements as women and children would walk or row distances to gather.

Trade

Ainu culture is highly diversified due to several differentiating factors between the islands which are the homeland to Ainu. Although Hokkaido, Sakhalin and Kurile are separated by narrow waters, they vary greatly in terms of ecological zones due to the differences in range of latitude. Geography as well as ocean currents contribute to the ecological differences resulting in variations of flora and fauna present on the islands[10]. These ecological differences result in regional cultural differences of Ainu

Due to these factors, Ainu of the different islands traded various resources that were available to them. Commonly traded items included pelts, hides, fish oils, dried fish and feathers. Kurile Ainu traded items such as the pelts of otters or foxes. Hokkaido Ainu commonly traded pelts and hides from bears, deer and seals. Sakhalin Ainu often traded hides from marten. In return for these items Ainu received goods such as metal pots, knives, swords and needles, rice, tobacco, cotton, silk, pipes and coins[10].

Governmental Policies

Over the course of history, Ainu were forced into assimilation as a result of the numerous discriminatory policies implemented by the Japanese government. The Ainu culture was facing extinction from the oppressive nature of both the government and society. Because Ainu traditions largely did not employ any method of writing, much of the history and origin of these people remain unknown and were erased. Over time the relationship between the government and Ainu has evolved which can be observed through the major policies put in place.

Meiji Restoration (1869-1882)

The Edo era came to an end in 1868 and marked the revolution that would soon take place known as the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji Restoration was recognized as a revolution in an attempt to establish a new political system with the establishment of the Meiji constitution[3]. This was a major turning point for Japan in terms of society, politics and the start of a modern industrial economy. 1869 marked the end of the Meiji Restoration and this led to the inclusion of Hokkaido, formerly known as Ezo-chi, as a part of Japan.

During this time, the Japanese government also began to recognize that Russia was attempting to expand their territories and sought to control more lands, especially those that were in an undeveloped state. This led to the division of lands and islands of Japan. Russia gained control over Sakhalin and Japan would continue to possess control over the Kuril islands. This forced the Ainu to determine their citizenship. Despite having to declare citizenship, the Ainu of these islands often recognize the nations of both Japan and Russia to be invaders of their lands.

Several Ainu were forced to leave their territories. Upon leaving their homelands, the new surroundings they inhabited were often discriminatory and did not present great lives for Ainu.

National Census (1871)

Historically, the Japanese government did not recognize that there were any minority groups present within Japan. It was only in 1871 that the Ainu peoples were accounted for and registered in the national census (kokusei chosa)[3]. Their ethnic diversity, language and customs would continue to not be recognized for years later. The census registration act was rather seen as a means of assimilation by the Ainu as it suppressed their cultures and forced them to adopt new lifestyles.

Ainu were forced to abandon their language and culture and conform to Japanese norms. Women and men were prohibited from getting tattoos and other markings which were significant to the Ainu cultures and traditions. Upon registering into the census, Ainu had to take on Japanese surnames which further contributed to the efforts of assimilation. The census registration act was a means of “ethnic cleansing”.

Immigration Support Rules (1869-1890)

During this period of time, the government of Japan was attempting to increase rates of emigration from the mainland to Hokkaido through a series of land laws for land development. Several aids such as the Immigrant Support rules were implemented to help promote the move from the mainland[3]. These rules would assist immigrants by providing the coverage of travel expenses, housing and resources such as tools for farming. Although these rules were beneficial for immigrants, they were in turn harmful to Ainu as it took away their traditional lands which were now declared to be in a state of no use resulting in them being available for development. The lands that were now accessible for development attracted many corporations and businesses to the islands and further damaged the territories of Ainu.

Several laws such as the Hokkaido Undeveloped Land Allocation Laws were also established during this period which continued to exclude the presence and the rights of Ainu on their territories.

Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act (1899-1997)

1899 marked the establishment of the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act which finally recognized and included Ainu peoples. Although it was inclusive and was presented as a means of protection of Ainu, it continued to ignore their traditional practices and customs. The act did not attempt to dispute the ban on hunting and fishing implemented by the government, but rather provided lands in order to promote farming which would inherently take away from Ainu land practices[3]. This land was distributed alongside a quota. If a certain level of success of farming could not be obtained within a range of 15 years, the land would be taken away. Many Ainu who could not meet the quota were forced into low wage labour jobs in mines or factories. Additionally, the government could also possess control over any and all production that was taking place on these lands.

This act was also used as a form of assimilation by promoting education where Ainu children were forced to adopt the Japanese language. The curriculum was formulated to ensure cooperation of Ainu by the central government. This act further led to the loss of Ainu culture, language, land and identity.

The Act on the Promotion of Ainu Culture (1997-)

In 1997 the Hokkaido Former Aborigine Protection Act was created. During this period there was the establishment of laws for the purpose of promoting the preservation of Ainu culture. These laws were formed through the collaboration of: “Ainu representatives, the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, the Hokkaido government, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, alongside the pressures from human rights and indigenous peoples’ groups. This period marked the government's acknowledgement and respect for Ainu knowledge and traditions.

The Act on the Promotion of Ainu Culture and the Dissemination and Advocacy of Knowledge in Respect to Ainu Traditions (Ainu bunka shinko-ho) was passed in 1997, the Ainu people were finally freed from the term kyu-dojin (former aborigine), which had stigmatized them for more than a century[3]. The social status and identity of the Ainu people have shifted dramatically over the period since this law took effect as the Japanese government had finally recognized Ainu to be a distinct People. Although there were changes being made, issues remain in terms of education, socioeconomic status and quality of life due to over a century of policies that had enforced assimilation and discrimination of the Ainu.

UNDRIP (2007)

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was created in 2007 in order to advocate for the rights and protection of Indigenous peoples[3]. Japan was in support of this declaration. Although not legally binding, Japan was now committed to creating a change in the treatment of Ainu and Indigenous peoples in Japan. There were now efforts being made to create a relationship between Ainu and non-Ainu as well as address the discrimination and mistreatment of Ainu.

Official Recognition (2008)

The Japanese government officially recognized Ainu as Indigenous peoples in 2008 with the passing of a resolution[3]. There were promises being made on the formulation of new laws and policies in favour of Ainu. In order to improve upon history, Ainu members were being included in the decision making and developing policies. In order to further promote change, some Ainu have chosen to work alongside global human rights groups or Indigenous groups to create a presence of external pressure.

Ainu in Biratori

The town Biratori in Hokkaido, is located on the northernmost island in Japan. This town is divided into 17 sub districts in which there is the highest number of Ainu communities residing in comparison to the remainder of Japan. Within these districts, there are many non-Ainu living in close relations with the Ainu[6]. It is difficult to obtain an accurate statistic of the Ainu population as the national census conducted by the government does not distinguish between Ainu and non-Ainu. There are approximately 1,577 people who self identify as Ainu that reside in Biratori. This does not include those who did not choose to disclose as Ainu due to social injustices and prejudices that are associated with the identification.

Archeological records suggest Ainu peoples and human settlements were residing in the Saru river region dating back from 6000 to 9000 years ago[6]. The Saru river region provided climatic and geographic conditions which were ideal for humans, wildlife and nature to flourish. The riverbanks were optimal places to settle where Ainu lived amongst large groups which were led by a male Elder. The evidence of settlement is supported by the presence of artifacts such as the remains of stockades (casi) which were found. Casi were understood to hold a cultural significance to the Ainu culture during that time.

Conflicts and a series of wars began around the year 1400 after the Japanese migrated to Hokkaida from the mainland as a result of confrontations. The Ainu eventually lost their power after the Shakushain war against the Matsumae Feudal Clan which led to the establishment of trading posts[6]. The trading posts regulated and managed all goods that would enter and leave the island of Hokkaido. The Ainu were forced to trade due to the oppressive trading system that was enforced. They traded kelp, parched small sardines, Shiitake mushrooms, salmon, etc.

By 1945, people from the mainland continued to immigrate to Hokkaido which resulted in Ainu becoming a minority group in Biratori. In response, Ainu came together and established their own administration and “gained legal status as a township”.

A large threat to Ainu livelihoods was the construction of the Nibutani dam in the Saru river by the Hokkaido Regional Development Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in 1973[6]. The purpose of the dam was to supply industrial water to areas as well as provide hydroelectricity and flood control. The construction of this dam resulted in the loss of traditional practices, dispossession and displacement of Ainu. The degradation of the environment was also present as there were negative impacts to the endemic species of salmon which Ainu livelihoods depend on. The Nibutani dam further contributed to the disturbance of traditional grave sites which hold sacred and historical values. Several other lands which were given to Ainu under the Former Aboriginal Protection Act for farming were also disturbed due to flooding. This resulted in a lawsuit brought forth by Ainu landowners in opposition to the construction taking place in the Saru river[11]. Unfortunately, the dam was completed by 1997 and no further attempts to decommission the dam were ever successful.

Ainu - Present Day

Revival Movements

The persistence of present day Ainu culture is a result of the efforts of Ainu people who have participated in revival movements, ensuring the passage of traditional knowledge and practices from the older to younger generations.

Women Lead Cultural Revitalization

Spearheaded by women, revival movements through motifs have been established as a response to the violence the settler state has enacted against Ainu communities. A harmful practice enforced by the Japanese government is the determination of Ainu ethnicity through methods such as blood quantums. In response to this practice, Ainu women's reclamation of traditional embroidery and cloth work practices can provide more ethical solutions to questions around Ainu ethnicity as motifs hold importance to the identity of Ainu people[8].

The forced assimilation of the Ainu to colonial culture gave women the responsibility of safeguarding traditional practices while men took the responsibility of assimilating. Women carried out knowledge exchange between the older and younger generations in private spaces to ensure the preservation of traditional knowledge and practices[8]. The connection between material culture and Ainu heritage is significant due to the ability of women to conduct these practices privately. Although it may appear that these revival movements are politically motivated, they are actually spiritually motivated practices. Ainu women view revival as an obligation to their ancestors, spiritual practices and the inheritance of Ainu motifs express the resistance of Ainu to assimilation and homogenization[8].

Urespa

Urespa, meaning "growing together" in Ainu, is a cultural revitalization and decolonizing non-profit association established in 2013 at Sapporo University. The goal of Urespa is to unite Ainu and Wajin (Japanese majority society) so students can learn the Ainu language and cultural practices together, forming a new way of practising Ainu culture in modern day urban settings[2]. It has established the first university scholarship for Ainu who wish to pursue a degree, allowing students to attend university and participate in Urespa's cultural activities outside of class. Non-Ainu community members are also allowed to participate in the activities offered by Urespa, in exchange for support of the program by a yearly membership fee. Lead by the students, Urespa is seen as a welcoming program to anyone who is interested in learning about Ainu culture[2]. The collaboration and co-learning between Ainu and Wajin students is a chance to rethink how the new generation approaches this issue, focusing on how each culture adds to and strengthens society[2].

Several Hokkaido institutions, such as the Ainu Museum, facilitates the resurgence of Ainu culture[4]. This museum holds traditional Ainu ceremonies, dances and folk art. The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture has taken responsibility for the training of Ainu language instructors, offering language classes, and holding speech contests[4]. Lastly, Sapporo Television broadcasts Ainu classes for beginners over the radio[4].

Ainu Identity

Colonial practices threatening traditional practices and the lives of the Ainu have altered how many Ainu currently see themselves in relation to their identity. The discrimination Ainu have faced because of their identity has resulted in many Ainu believing it is better for them to blend into Japanese society and hide who they are[1]. Although not all Ainu feel this way, the varying degrees to which different Ainu people take pride in their identity is likely a product of colonial practices such as forced assimilation that have prohibited many traditional practices. There are many Ainu in the younger generation who don't take interest in Ainu culture until they get older and become more aware of their identity. It is currently estimated that 66% of Ainu youth don't have awareness of the fact that they are Ainu[12]. For example, an Ainu student named Shingo, who is a part of the Urespa program, said that when he was younger, before joining the program, he had a negative outlook on Ainu culture. Once he began taking classes, learning the Ainu language, and engaging in Ainu cultural activities, he started taking pride in his culture and felt enthusiastic about learning more[2].

Fishing Rights

The Japanese government's recent acknowledgement of the Ainu as Indigenous peoples in 2019 was a step forward, but the government still needs to take action to acknowledge self identification and tribal rights of the Ainu. The decreasing population of the Ainu due to assimilation has lead the Japanese government to argue that no tribes hold rights over their territories, and therefore salmon fishing[13]. With this argument, the Hokkaido government placed bans on salmon fishing in rivers, making the activity illegal. The implementation of this law now requires the Ainu to receive permission from the government to practice their traditional hunting on their own lands. The Ainu have filed a lawsuit as a response to this law, fighting for exemption. Despite the removal of their rights and forced assimilation during the Meji period, the Ainu are arguing that their ancestors passed down their right to fish for salmon. They are also arguing that the government has yet to offer a legitimate reason for impeding the Ainu's use of their natural resources[13].

Assessment

Japanese Government

The Japanese government has continuously utilized its power to conduct acts of colonial violence towards the Ainu, ignoring the longstanding relationship they have with their territory and their right to self-determination[8]. Through most of history the government has targeted Ainu culture as inferior, using their power to force cultural homogenization on them, in attempt to erase their identities. Only recently has the government begun to shift policy and work towards the recognition of Ainu rights[3].

The Ainu

The Ainu have taken part in many movements to protest their treatment by the Japanese government. They have taken part in legislative activism, international activism at the United Nations and the Human Rights Committee, Judicial activism, and activism around a more effective adoption of UNDRIP by the Japanese government[8]. These substantial efforts have resulted in gains for Ainu society, as the Japanese government now recognizes them as an Indigenous people of Japan and has given support through funding for cultural activities. Although these are wins, the Japanese government still refuses full recognition of Ainu rights, meaning the Ainu will be forced to continue their legal mobilization to fight for self determination[8].

Recommendations

Through the use of revival movements and advocacy for their rights, the Ainu have remained resilient against the violent attempts of the Japanese government to assimilate them. However, the Ainu would benefit greatly from shifts in the policies of the Japanese government to increase support for Ainu sovereignty. This is prevalent in the government's lack of recognition of Ainu fishing rights, which has disregarded the importance of Ainu traditional practices and allows the dispossession of Ainu resources[13]. Although the government has finally recognized the Ainu as Indigenous Peoples, there are still many shortcomings in the recognition of sections of UNDRIP that include the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples[8]. This can not be ignored by the Japanese government. If no action is taken, the Ainu will continue to practice legal mobilization to continue the fight for their traditional rights.

Aside from improving the recognition of Ainu rights, the Japanese government can work towards reconciling wrongdoings by supporting Ainu community and revitalization efforts, such as Indigenous education initiatives. The current status of Ainu education is not conducive to self-determined Indigenous education, impacting the performance of Ainu youth as they are forced to navigate colonial education systems that invalidate Indigenous knowledge[12]. Because of the attempts of the Japanese government to force assimilation on the Ainu and erase their traditional knowledge systems, the government should be righting these wrongs by providing resources to the Ainu that can aid in the establishment of their own educational institutions and Indigenous curricula[12].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Cheung, S. C. (2003). Ainu culture in transition. Futures, 35(9), 951-959.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Uzawa, K. (2019). What does Ainu cultural revitalisation mean to Ainu and Wajin youth in the 21st century? Case study of Urespa as a place to learn Ainu culture in the city of Sapporo, Japan. Alternative: An International of Indigenous Peoples 15(2), 168-179.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Okada, M. V. (2012). The plight of Ainu, indigenous people of Japan. Journal of Indigenous social development, 1(1).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Shim, K (2004). "Will the Ainu language die?". Panorama- Taking it global.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Ohnuki-Tierney, E (1974). Another look at the Ainu—a preliminary report. Arctic Anthropology. pp. 189–195.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Iwasaki-Goodman, M; Ishii, S; Kaizawa, T (2009). "Traditional food systems of Indigenous Peoples: the Ainu in the Saru River Region, Japan". Indigenous peoples' food systems: the many dimensions of culture, diversity and environment for nutrition and health: 139–153.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Joy, Alicia (March 20, 2017). "Rituals, Festivals and Celebrations of the Indigenous Ainu of Japan".

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Hudson, M. J. (2013). Ainu and hunter-gatherer studies. Beyond Ainu Studies: Changing Academic and Public Perspectives, 117.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1981). Illness and healing among the Sakhalin Ainu: A symbolic interpretation. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521236362.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Tierney, E (1976). "Regional variations in Ainu culture". American Ethnologist. 3 (2).

- ↑ "Nibutani Dam on Ainu homeland, Japan". Environmental Justice Atlas. 2019. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Gayman, J. (2011). Ainu right to education and Ainu practice of ‘education’: Current situation and imminent issues in light of Indigenous education rights and theory. Intercultural Education, 22(1), 15-27.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Kyodo News. (2020). Ainu minority files lawsuit against government on salmon fishing rights.