Course:CONS370/2019/Contemporary fishery management in Aotearoa New Zealand: inter-Maori relations and the government's role in redress

The state of Māori rights in marine territories and fisheries has changed significantly in New Zealand since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 and most prominently in the last 30 years. In 1986, the New Zealand Government adopted a Quota Management System (QMS) which dictates the Total Annual Catch (TAC) allowance of every fish stock to be shared between commercial, recreational and customary fisheries. The allocation of these quotas has resulted in major conflict between stakeholders, with Māori arguing that initial allocations were in breach of Treaty agreements. In the ensuing legal battles it seems a ‘divide and conquer’ strategy was adopted by the Crown, enabling the Government to step back and allow inter-Māori turmoil (namely between hapū (tribes) and decentralized ‘urban’ Māori) to run its course.

More recently, with the final settlement of fishery Treaty claims in 1992, Māori entitlement to ancestral territories has been more deeply acknowledged, resulting in increasing co-management nationwide through government-issued Taiāpure and Mātaitai Reserves as well as Rāhui (temporary harvesting bans). Using these tools, Māori have been able to reinstate their rights of rangatiratanga (chieftainship or guardianship) over traditional fisheries and established a new balance of power between Māori, the Crown or the nation-state, recreational users, and commercial fisheries. This page analyses Government fishery management and inter-Māori relations over time in New Zealand.

Description

Fisheries management in New Zealand has seen many changes over the years since European settlement and the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. New Zealand consists of a group of Islands located in the southwest Pacific, and was originally inhabited by the seafaring Māori peoples who enacted traditional management strategies to prevent unsustainable exploitation. Customary harvesting of kaimoana (seafood) was an important part of the Māori culture, particularly for daily consumption, traditional feasts and trading between tribes (Lock & Leslie, 2007; Hale & Rude, 2017).

Initial European discovery of New Zealand is attributed to the Dutch Abel Tasman in 1642 followed by James Cook in 1769, after which European visitation significantly increased until the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 (Hale & Rude, 2017). The Treaty of Waitangi was instigated to encourage peace, partnership and co-habitation between populations and was signed by both British and Māori representatives, establishing the British Crown as sovereign over the land while Māori could retain ‘tino rangatiratanga’ (authority) over their territories and resources, thus guaranteeing Māori ‘undisturbed possession’ of land and fisheries until they chose to hand them over or sell them to the Crown (Treaty of Waitangi, 1840; Memon & Cullen, 1992; Lock & Leslie, 2007; Hale & Rude, 2017). This agreement was soon breached, resulting in significant adverse cultural impacts. Specifically, the loss of food species and harvesting bans caused undermining of the ability of Māori to provide adequate hospitality; loss of indigenous food gathering, preparation and management knowledge; and a decline in the passing of previously relevant traditional stories, directly impacting iwi and hapū identity (Dick et al., 2012). In 1975 the Treaty of Waitangi Act was instated, establishing the Waitangi Tribunal to settle claims. This has had a great impact on the state of Māori fishery rights within New Zealand, and a full fishery settlement was completed in 1992. This was not, however, the end of advances for Māori input in fishery management. With increasing emphasis on co-management, the development of Mātaitai and Taiāpure Reserves and use of Rāhui have increased across the nation, thus further normalising customary rights of Māori who make up just under 15% of the population of New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand, 2013; Hale & Rude, 2017).

Tenure arrangements over time

Pre-1980’s

Prior to the establishment of a quota system in New Zealand fisheries were carried out under an ‘open access’ regime based on British Common Law, with no clearly defined rights of access or exclusion. In the 1700’s and 1800’s there was a thriving sealing industry which attracted ships from Australia, Britain and the United States. Entry limitations were introduced in 1866, however Māori were not afforded substantial legal recognition (or exclusion) during this time (Bess, 2001; Hale & Rude, 2017). Some legislation - namely the Māori Councils Acts (1900 and 1903) and the Māori Social and Economic Advancement Act (1945) provisioned for exclusively Māori reserves to be set up, however these were not acted upon and were repealed in 1962. No such rights have been offered since (Lock & Leslie, 2007). During this time there was minimal to no consultation with Māori, and the establishment of the first Fisheries Act in 1908 further eroded rights set out in the Treaty of Waitangi (Hale & Rude, 2017).

Early to Mid-1980’s

In 1983, the Fisheries Act established a quota system, further developed in 1986, signalling the initiation of the Quota Management System (QMS) - a type of rights-based management framework which acts to ‘privatise the oceans’. Quota holders may be individuals, companies, cooperatives or collectives, or in special cases may be a part of territorial use rights. Quota holders may buy, sell and trade their harvest quotas on the free market as ‘freehold’ property, termed Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) (Boast, 1999; Hale & Rude, 2017; Fisheries New Zealand, 2019a). ITQ’s are assigned to participants annually as a portion of the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) allocated for each species, and are held for one year. They are assigned on a ‘slice of the pie’ basis, relying on the TAC allowance of that year (Boast, 1999; Fisheries New Zealand, 2019a). Rights of ITQ’s include transferability, long-term access, right to harvest, and to seek accountability if use rights are diminished or extinguished. ITQ rights do not exclude use of an area by other fisheries or non-fisheries users, however some non-fishery activities may be constrained where they impact fishing. In New Zealand, these ITQ rights were initially freely tradeable, though they had to remain under New Zealand ownership (Hale & Rude, 2017). The original QMS scheme acted to cancel 46% of permits, ones which were deemed ‘unused’ or ‘part-time’, to streamline quota management, however many of these quotas were owned by Maori using the quotas to provide for their families, and supplement low incomes (Hale & Rude, 2017). In response to this, the Muriwhenua claim was filed by five Northland iwi in 1985 regarding the erosion of their customary fishing rights and numerous Treaty breaches by the Fisheries Act (1983). This resulted in Māori rights to fisheries being officially declared by the Waitangi Tribunal and the High Court for the first time, and increased awareness within the Māori community regarding their rights under the Treaty agreements (Bess, 2001; Sinner & Fenemor, 2005; Lock & Leslie, 2007).

Late 1980’s - Early 1990’s

However, the Government was slow to enact court advice from the Muriwhenua case, and only minor adjustments were made to QMS legislation, stating that no regulations under the Fisheries Act (1983) would affect the taking of fish by Māori for a “hui [meeting], tangi [funeral], or traditional noncommercial fishing use” (Hale & Rude, 2017). Thus, additional litigation was filed by Ngāi Tahu (the largest Māori iwi, located in the South Island) in 1987 challenging the allocation of quotas and highlighting the breach of the customary fisheries rights of Māori under the Treaty of Waitangi, arguing that they were the rightful owners of the entire fisheries resource, though they would be willing to bestow 50% to the Crown as a token of peaceful co-habitation and cooperation (Boast, 1999; Bess, 2001; Lock & Leslie, 2007). In response the Waitangi Tribunal proposed a settlement in quota (Lock & Leslie, 2007; Hale & Rude, 2017).

Treaty settlement of claims occurred in two stages: the initial interim agreement occurred under the Māori Fisheries Act 1989, where 10% of the total quota was transferred from the Crown to the Waitangi Fisheries Commission, along with fishing company shareholdings and $50 million. The commission was set up to hold these assets on behalf of the Māori until agreement could be reached with regards to how these assets would be shared among iwi or tribes (Boast, 1999; Bess, 2001; Walrond, 2006; Lock & Leslie, 2007). This interim settlement also partially included non-commercial fisheries through development of Taiāpure, a type of local marine management formed in locally important fisheries and managed under a committee representing local Māori. However they were given no real management authority beyond providing recommendations to Government (Memon & Cullen, 1992; Hale & Rude, 2017). In 1992 the final settlement was reached under the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act, known as the ‘Sealord deal’, in which 50% of Sealord fisheries - a major commercial fishery in New Zealand - and 20% of all new species introduced into the quota system, a further $18 million cash, and more fishing company shares were transferred to Māori via the Māori Fisheries Commission managing body, Te Ohu Kaimoana (TOKM) (Boast, 1999; Walrond, 2006; Lock & Leslie, 2007; Hale & Rude, 2017). Along with this, regulations were put in place to ensure that 20% of Māori-allocated quotas must be sold amongst Māori groups rather than on the open market (Hale & Rude, 2017). This concluded fishery Treaty negotiations, resulting in Māori becoming a significant industry player, increasing their influence in national fisheries.

1990’s - 2004

In 1993, the need to recognise customary fishing rights was divided into two actions: providing tangata whenua (caretakers of the land, i.e. Māori) the ability to gather food, and recognising the special relationship between Māori and mahinga kai (significant food gathering places). This resulted in the development of Mātaitai Reserves, which empowered Māori management and authority over marine areas through the ability to pass local bylaws over and above Taiāpure and general regulations (Hale & Rude, 2017). In addition to this, the 1996 Fisheries Act amendments made provision for Māori use of Rāhui (temporary harvesting bans) for up to 2 years in order to protect fishery stocks (Lock & Leslie, 2007).

After Treaty settlement, it was not until 2003 that it was agreed how assets would be shared amongst Māori iwi. It was eventually agreed that 50% of assets would be held centrally, and in 2004 Te Ohu Kaimoana was assigned to oversee these (Walrond, 2006; Lock & Leslie, 2007). The remaining 50% would be allocated to iwi based on coastline (inshore fisheries) and a mix of coastline and population size (offshore fisheries) (Hale & Rude, 2017). Some special allocations and additional cash payments were also made to prevent disadvantaging certain iwi (Lock & Leslie, 2007).

Current day

In addition to current Māori rights to TACC (Total Allowable Commercial Catch) in the form of ‘freehold’ ITQ property as noted above, Māori also retain customary use rights, enabling them to collect kaimoana for traditional events and feasts, as well as other non-commercial uses as laid out by the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act (1992). This includes rights to have input into the management of fisheries (via Taiāpure, Mātaitai and Rāhui) and the protection and development of QMS as part of the continuing relationship between the Crown and Māori (Lock & Leslie, 2007).

Administrative arrangements in the modern day

Government Management

In the QMS system of New Zealand, the Government sets policy, provides research and management services, and defines maximum sustainable harvest through yearly Total Allowable Catch (TAC) limits. TAC’s are set by the Ministry of Fisheries with advice from Fisheries New Zealand, and after an allowance is set aside for customary and recreational fishing, the remainder of the quota shares are assigned as TACC (Lock & Leslie, 2007; Fisheries New Zealand, 2019a). Individually, commercial participants (i.e. ITQ holders) have an Annual Catch Entitlement (ACE) per species based on TAC limits - including shellfish, crustaceans, seaweed and fish - to encourage sustainability. It is the government’s duty to manage and control compliance with these limits, with financial penalties applied to breaches of ACE (Hale & Rude, 2017; Fisheries New Zealand, 2019a).

Stakeholder Management

There are also organisations set up to allow commercial stakeholder representatives to enact management and provide services for the efficient operation of the QMS, such as Commercial Fisheries Services Limited (FishServe) which is completely owned by the fishing industry (Hale & Rude, 2017). In addition to this, small scale fisheries and community participants can participate in management through Taiāpure committees.

Indigenous and Community Management

Taiāpure (local fisheries):

The first genuine attempt at providing Māori with management rights over fisheries occurred with the passing of the 1989 Māori Fisheries Act and the initiation of Taiāpure - a type of reserve which recognises the rights of Māori to care for areas which have significant food, cultural or spiritual value (Memon & Cullen, 1992; Boast, 1999; Lock & Leslie, 2007; Fisheries New Zealand, 2017). These reserves allow for management by the local community, including a committee of Māori representatives, who can make management suggestions to the Government. Committees must be approved by the Minister of Fisheries in consultation with the Minister for Māori Development (Lock & Leslie, 2007; Fisheries New Zealand, 2017). There are no restrictions on types of fishing that may occur here, unless regulations are recommended and approved by the Ministry of Fisheries, and reserves may only be formed in nearshore coastal waters and estuarine habitats (Memon & Cullen, 1992; Boast, 1999; Fisheries New Zealand, 2017). This, along with the long and complex procedures around applying for Taiāpure - including public inquiry and Māori Land Court - means that few have been established (Boast, 1999; Lock & Leslie, 2007; Fisheries New Zealand, 2017).

Mātaitai:

Section 34 of the 1992 Settlement Act required that provision be made for both customary food gathering and the protection of places deemed as important mahinga kai (food gathering places). This resulted in the development of Mātaitai Reserves. These were much easier to obtain than Taiāpure, though still required approval by the Minister of Fisheries based on certain criteria such as aims in line with national sustainable management goals, proof of a significant relationship between tangata whenua and the area, and assurance that regulations will not affect the ability of quota holders to obtain their ACE (Lock & Leslie, 2007). As a result, there are 46 Mātaitai Reserves in total, compared to only 10 Taiāpure nationwide (Fisheries New Zealand, 2019b). Mātaitai may include both coastal and internal waters, and are managed by the local Māori iwi or hapū (tangata whenua) through the implementation of bylaws regarding restrictions or prohibitions on the gathering of certain fish, aquatic life or seaweed within reserve areas (Boast, 1999; Lock & Leslie, 2007). These bylaws have to be consistent with national marine laws, and are enacted equally across the non-commercial users of the area (breaches of which are penalised by the Crown only). Bylaws may not, however, affect access of the public to beaches and rivers, alter access to private land, or control whitebait fishing. Commercial fishing is often prohibited in these reserves also, allowing further protection of fishery stocks and mahinga kai (Fisheries New Zealand, 2017).

Rāhui:

Rāhui is a traditional process introduced with the renewal of the Fisheries Act in 1996, and applied by Māori to temporarily ban access or harvest in a certain area in order to allow fishing stocks to recover. Rāhui are temporary prohibitions which carry poaching penalties, and can be put in place in marine areas for up to 2 years with application to the Ministry of Fisheries by local tangata whenua (Lock & Leslie, 2007).

East Otago Taiāpure - Case study

The East Otago Taiāpure was established in 1999 after a seven year application process begun by the local Kāti Huirapa Rūnaka ki Puketeraki in 1992, a time where this was the only available option for customary fishery management (Fisheries (East Otago Taiāpure) Order 1999; Jackson et al., 2018). The application process involved numerous hearings in the Māori Land Court, hui and public meetings, and national political changes. Originating from concerns around depletion of fishery stocks, particularly pāua, and the effects this was having on local Māori customary activities, as well as the desire to assert rights of rangatiratanga (chieftainship) to preserve mahinga kai, the reserve is now in its 20th year of active operation and the values of rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga (physical and spiritual guardianship) remain at the centre of management goals (Jackson et al., 2018). The management committee was established formally in 2001 and includes 50% local hapū representatives alongside 50% community membership including the East Otago Boating Club, Karitane Commercial Fisherman’s Co-operative, the University of Otago and River-Estuary Care: Waikouiti-Karitane. The aims of this committee include ensuring continued customary, recreational and commercial fishing access and harvesting rights; actively promoting traditional customs of local Māori; strengthening resilience of the area to human activities; and ensuring reserve fisheries remain healthy and fit for consumption. Management practices utilised in this case include catch limits, set net regulations, and a pāua harvesting exclusion zone from 2012-2014. This has greatly benefited marine populations in the area, allowing not only sustainable management but also further ecosystem restoration (East Otago Taiāpure Management Plan, 2008; Ministry for Primary Industries, 2017; Jackson et al. 2018).

Affected stakeholders

Māori

Māori populations are organised under three main social structures - the whānau (family groupings); the hapū (a group of whānau); and iwi (tribes, made up of hapū). Individuals are often aligned with multiple iwi through whānau and hapū connections. There are currently 58 iwi recognised by the Māori Fisheries Act (2004), of which only 9 are located in the South Island and Stewart Island which comprise over half of the coastline of New Zealand (Hale & Rude, 2017). In the past (prior to the Muriwhenua case) many Māori did not understand the importance of fisheries legislation and how this might impact their customary fishing rights, as there had been an abundance of kaimoana available and therefore no major practical impacts on livelihoods up to this point (Lock & Leslie, 2007). The Muriwhenua case highlighted the increasing erosion of Māori Treaty rights, and sparked a turning point in Māori understanding of the significance of full, exclusive and undisturbed possession of fishery resources. A study carried out by Dick et al. (2012) identified considerable adverse cultural effects on Māori related to previous harvest bans and loss of significant species, such as the inability to provide adequate hospitality; loss of traditional harvesting, preparation and ecosystem knowledge; and the decline of relevant traditional storytelling involved in community bonding, resulting in direct erosion of Māori culture and identity.

After the final settlement was agreed upon between the Crown and Māori, an unprecedented debate took place regarding the allocation of settlement assets between Māori groups, largely due to the potential for financial gain (Lock & Leslie, 2007). Conflicts arose initially between rural tribal Māori and dislocated urban Māori, however inter-tribal controversy soon developed and divisions were broadly separated into three main factions - ‘populationists’, wishing to assign assets by population (generally tribes with larger populations and smaller coastlines); ‘coastliners’, preferring division of assets by coastline (generally tribes with smaller populations and larger coastlines); and a mix of the two. Eventually a mixed approach was agreed upon and integrated in the 2004 Māori Fisheries Act. This required reorganisation of traditional Māori groupings to include Mandated Iwi Organisations (MIO’s) for management of assets, essentially formalising iwi and forcing adherence to Government standards, which could only then be recognised in legislation (Bess, 2001; Hale & Rude, 2017). The ultimate effects of this conflict and restructuring continue today.

Inter-Tribal Māori Controversy

The main objectives of tribal Māori have been to enact their rights of rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga on their traditional marine territories as outlined in the Treaty of Waitangi (Jackson et al., 2018). However the various iwi of New Zealand have developed varying influence in decision making over time due to the relative lack of cooperativeness of Māori leaders, and the marginalizing of less Crown-favourable influences. For example, the Te Rūnanga o Muriwhenua Incorporation (consisting of Northland tribes), was a strong objector of the Commission's "mana whenua/mana moana" model which emphasised population size over coastline length. They represented iwi who would not benefit economically from the settlements and were already significantly disadvantaged within New Zealand, with high unemployment and few other resources. The Muriwhenua population of 18,492 relied heavily on fisheries, while the South Island’s major iwi, Ngāi Tahu, had a much larger population of 22,269, thus based on this model, Muriwhenua gained only $203.92 per capita, while Ngāi Tahu benefited 22 times more, with $4533.24 per capita (Boast, 1999). In reality, it seems the controversies between Māori tribes were exacerbated by the government stepping back from court proceedings and taking a ‘fight it out’ approach, allowing inter-Māori conflict to escalate (Boast, 1999). It was by this process that Ngāi Tahu came to dominate Treaty negotiations, particularly in the South Island, while other iwi who would often act independently were sidelined - some entirely rejecting Ngāi Tahu’s recent dominance (Webster, 2002).

Urban Māori

Alongside controversies between iwi groups, there was also a severe struggle between decentralized urban Māori and their rural counterparts. This conflict began with the mentioning of ‘all Māori’ in the 1989 Fisheries Act and the 1992 Settlement Act, without further explanation of who that should encompass. As of 2002, over 80% of Māori lived in urban areas, and at least 25% of Māori did not know their iwi, or chose not to affiliate with an iwi (Webster, 2002). The main question is whether ‘Māori’ was supposed to mean some kind of federation of autonomous iwi or whether it meant simply a sector of the general population of the country differentiated by an ethnic criterion. Secondly, it had to be decided whether the settlement was to benefit everyone who happened to be Māori, or whether it was intended as a restoration of property rights to specific groups based on territory, historic involvement in marine fishing or some other criterion of tribal connection to the resource (Boast, 1999). During this mid-1990’s struggle, some organizations advocated asset allocation to iwi while others advocated to ‘all Māori’ including urban Māori, fearful that they would be left out of fishery settlement proceedings and resulting compensation. The two main organizations which advocated allocation to iwi (the Treaty Coalition and the Area One Consortium) came to characterize themselves as ‘iwi fundamentalists’. Objection to this came from the ‘Urban Māori Authorities’, which was created by mutual benefit, social welfare, and trust organizations in the 1980's. There has been major conflict between iwi fundamentalism and the Urban Māori Authorities which the Government made no significant moves to address, and this often resulted in expensive and high profile court cases. It is important to note, however, that the claim of the Urban Māori Authorities to represent Māori living in urban areas has been argued to be highly contestable in itself (Boast, 1999).

The Commission argued that Māori living in urban areas must belong to some iwi if they can be meaningfully said to be ‘Māori’ at all, and that urban Māori would benefit from assets being allocated to iwi regardless, as they would then apportion interests to the members of the iwi wherever they happen to live. In saying this though, the term ‘iwi’ has been given a new and perhaps artificial significance over time, as it can be taken to mean ‘the people’ as well as ‘tribes’ and this ambiguity has allowed the Government to mould its definition to its convenience (Boast, 1999). The High Court ruled that iwi meant simply "people of the tribe", and thus only iwi were to be allocated assets, however the Court of Appeal then ruled that the Commission had to make separate provision for urban Māori (Boast, 1999; Hale & Rude, 2017). This eventually led to the provision for non-iwi affiliated Māori in the final Māori Fisheries Act (2004).

Interested stakeholders

The New Zealand Government and the Crown

Defining the term ‘the Crown’ can be a complex task. In general it is used to describe the rule of the British Monarchy and the subsequent independent New Zealand nation-state after the establishment of the Commonwealth. Currently, New Zealand is ruled by the New Zealand monarch - the same monarch who holds the British crown, though it is considered a separate rule. This separation has allowed independence of the New Zealand nation-state from British rule, and the British government can no longer advise on matters regarding the New Zealand state. The term 'the Crown' has thus been transferred to the the New Zealand nation-state which retains the power of veto over national decisions. The Treaty of Waitangi was signed as an agreement between the British Crown and Māori in 1840 to incorporate New Zealand into the growing British Empire.

Within the New Zealand Government the Executive arm is the governing body with the greatest national decision making power, charged with the day-to-day management of state affairs through making, application and enforcement of law on behalf of the Crown (the nation-state). It is in part subject to the judiciary system in which judges of the Supreme Court can rule on civil or criminal matters and rights breaches. The Government is a democratically elected, fluctuating system of authority, while the nation-state (the Crown) is constant and unchanging. Therefore, the population of New Zealand has a large influence on the Government of the time but little to no influence on the ruling of the Crown. The Government maintains a degree of freedom from the Crown, however, as the Crown is not involved in all national decision making - though it retains the power of veto should it choose to use it. The Crown is a major actor in many fields of activities including Treaty settlements, land disputes, coastal protection and fishing rights. In terms of the actual management of these issues however, it retains a more distant stance allowing Government to act as a buffer or scapegoat from whom redress can be sought (Shore & Kawharu, 2014). On the other hand tactical use of the Crown has also been made by the Government, portraying it as an unchallengeable higher authority with ultimate power over decisions - for example during the 1996-2004 negotiations of asset allocation between Māori - thus deflecting blame when it is necessary to be seen as neutral and avoid accusations of bias or conflicts of interest (Shore & Kawharu, 2014).

Large Commercial Fisheries

The influence of large commercial fisheries on decision making is largely attributable to their scale and economic power. Currently, only 8 companies own roughly 75% of quota, affording them significant lobbying power. There are also fishery-owned organisations such as FishServe that have been set up to allow commercial stakeholder representatives to provide services, QMS management and lobbying for commercial stakeholder interests (Hale & Rude, 2017). However, as the 1992 Settlement Act resulted in the Crown providing $150 million for Māori to enter into a 50/50 joint venture with Brierley Investments Ltd. in the purchase of Sealord Products Ltd.(Bess, 2001), the structure of some large fishery companies have come to include Māori interests. For example, Sealord is now 50% owned each by Māori Aotearoa and Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd (a leading Japanese fishing company). Sealord has about 30 percent of the deep-sea fish catch quota in New Zealand, including an ITQ of about 130,000 tonnes in New Zealand's exclusive economic zone. Additionally, Sealord’s boats are allowed to fish in Māori-owned fisheries due to the 50% stake acquired by Māori. Along with this, company shares that iwi hold, whether in their allocation or in a central cooperative, are to be restricted from sale in some way in order to protect the patrimony from an unfettered free market (Webster, 2002). Thus, the power of large commercial fisheries is not necessarily exclusive of Māori rights. Big fishery companies can also help Māori to maximise their share of the fisheries by providing improved technology and access through relationships of mutual benefit and cooperation.

Small Commercial Fisheries

Small fisheries have influence on decision making through active engagement with Taiāpure committees, public inquiries during reserve applications, and through organisations set up on behalf of multiple small enterprises to allow increased influence and lobbying (Lock & Leslie, 2007; Fisheries New Zealand, 2017; Hale & Rude, 2017). Additionally, ACE is more widely held and less concentrated in the inshore fishery, thus providing more opportunities for small-scale fisheries in inshore zones (Stewart & Callagher, 2011).

Local Communities and Individual Recreational Fishers

Originally, some communities were hesitant to support Taiāpure and Mātaitai development due to fears of public access exclusion to beaches and fisheries. In practice, however, these fears have not materialised due to regulations within the Fisheries Act 1996 ensuring that bylaws and regulations apply to all users evenly, preventing Māori preferential access (Fisheries New Zealand, 2017). To enforce this, Taiāpure committees are required to include members of the local community, as illustrated in the East Otago Taiāpure example above (East Otago Taiapure Management Plan, 2008). More recently, the benefits for all users of managed reserves acting as nurseries and fish replenishment zones have been acknowledged, and conflicts regarding the development of new reserves have largely been around impacts of regulation increasing fishing pressures on nearby fisheries. These conflicts can delay proceedings for years, however they seldom prevent reserves from being established - rather only affecting their size and location (ODT 2010; ODT, 2011).

Animal Welfare Organizations and Environmental Organizations

Animal welfare and environmental organisations also have the ability to lobby for or against Mātaitai and Taiāpure through public inquiries and hui (community meetings), and impact other decision making through the courts (Fisheries New Zealand, 2017). It is worth noting here that in comparison with the rest of the world, New Zealand’s QMS has resulted in major positive outcomes in prevention of overfishing and associated impacts on other components of the ecosystem including bycatch (Mace et al., 2014; Hale & Rude, 2017). However, consideration of other species is often highlighted in debates, including birds and endangered native dolphins.

Assessment

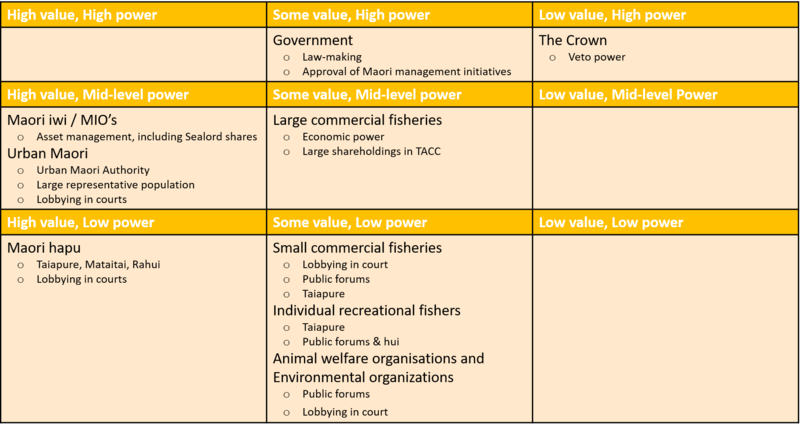

The complex interrelations between stakeholders, particularly the different Māori groups, can be hard to tease out. As Figure 3 shows, the Maori community can be classified beyond urban and tribal Maori into westernised and traditional factions. In the Government’s view, there are also more or less cooperative Māori, like Ngāi Tahu vs. Muriwhenua. This enables empowerment of certain groups over others within one seemingly simple and neutral stakeholder group (Boast, 1999). Westernised Māori tend to take the stance that ‘all Māori’ should encompass anyone of Māori descent, including urban and decentralized Māori. However traditional ‘iwi fundamentalist’ Māori argue that urban Māori have chosen to leave their traditional tribes for a more affluent urban life, and thus only regard Māori choosing to remain affiliated with iwi as viable under regulation (Webster, 2002).

In the modern-day, iwi exercise significant political power in the recovery and management of fisheries and assets in New Zealand through MIO’s. The Urban Māori Authorities are a powerful group as well, representing a large portion of Māori as the population of urban Māori is increasing. Based on census statistics, the number of persons acknowledging Māori descent increased by 13 percent after settlement between 1991 and 1996 (to 579,714 in 1996). Simultaneously, over 10,000 Māori signed up with the Urban Māori Authority upon releasing their mandate to demand a share of the fisheries allocations regardless of iwi affiliation (Webster, 2002). With increasing population size, high numbers of urban Māori elite, and with support from many social organizations, urban Māori have become a powerful group and can have a large lobbying impact on New Zealand politics.

The Government have the highest power of the three main stakeholders (the Government, urban Māori and iwi/tribal Māori). Despite being originally repressed, the increasing power of both iwi and urban Māori has not only enabled the settlement of Treaty claims and encouraged peaceful co-management and co-habitation, it has also set up a new, more balanced power regime allowing future conflict to be more fairly resolved.

Discussion

International Views and the Literature

The tone of literature discussing indigenous fisheries management in New Zealand has changed markedly over the last 30 years, with local literature tending to be more critical than international assessment (Hale & Rude, 2017). During the 90’s the tone was rather pessimistic, as with Memon & Cullen (1992) and Boast (1999) - both independent university research projects which criticised the Government and Crown for ignoring or exploiting Māori for so long; allowing inter-Māori conflict to escalate without intervening; and being hesitant to change the tides by acknowledging customary fishery rights. From the 2000’s onwards, however, a significantly more positive outlook is apparent, with a tendency to focus on framing the New Zealand QMS as an example of long term and successful management for international fisheries worldwide to draw upon, having overcome numerous complications and difficulties. Reports such as Lock and Leslie (2007) and Hale and Rude (2017) demonstrate this. Lock and Leslie (2007) is a report written for the New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries analysing performance over 20 years of QMS implementation, gathering information from academia, legislation, and persons who were involved in processes of change over time. This report claims, as others do, that New Zealand is a world leader in the use of ITQ and QMS in fisheries management despite, or due to, the many improvements that have had to be made since its instigation in 1986. Hale and Rude (2017) is an international Nature Conservancy report aimed at providing advice for active conservation, developed through a 9 month project gathering information from members of Government, Te Ohu Kaimoana, the Fishing and Seafood Industry, environmental NGOs, academia, iwi, and recreational fishing groups. These two reports are just an example of the many who hold New Zealand’s fishery management in high esteem in the global setting.

Successes and Failures

In a sense, the aims of Māori have been largely achieved, particularly in reinstating customary rights to New Zealand’s fisheries and empowering the enactment of traditional rights of rangatiratanga (chieftainship) and kaitiakitanga (guardianship) (Jackson et al., 2018). Furthering this, the establishment of customary management provisions such as formal reserves and Rāhui have allowed promotion of co-management and sustainability values and peaceful co-habitation with the Crown. This has grown to include not only the input of Māori, but of entire communities through Taiāpure management regimes and public meetings at various levels so as to ensure all stakeholders, including community members, local small scale fisheries, larger commercial fisheries, and wildlife and environmental organisations all have a seat at the table. Thus, the work that has been done can be seen as a significant step up from the place of very minimal rights which Māori were subject to 40 years ago.

In spite of this, there have been some critical issues which have been and have yet to be addressed. Conflict resolution and management of critical issues are largely in the domain of the Government and courts. The status of the Government as overseer can be seen as a positive structural move as it simplifies the national system, however it can also be argued to be a facilitator of inequality through forced hierarchy and, as seen in the past example of taking the ‘backseat’ stance in inter-Māori conflict (Boast, 1999), is not always held responsible for acting on these duties. However in these cases, often the courts become a useful tool to aid in conflict resolution from a more neutral standpoint. Small scale conflicts, in contrast, can be addressed through hui, local co-management committees, lower level courts and public forums which allow conflicts to gain a larger audience including commercial, local and customary fisheries interests (Hale & Rude, 2017). There are some concerns, however, that there is insufficient communication occurring between recreational and commercial fisheries in the new largely self-governing system of fisheries in New Zealand, and this dialogue is an important missing piece of the management puzzle (Hale & Rude, 2017).

Since the settlement of Treaty claims in 1992, Māori have successfully received markedly increased benefits from the continued development of the QMS and community and customary management structures, including commercial quotas, shares and cash payments, and recognition of customary fishing rights through development of reserves to enable Māori to enact traditional rights of rangatiratanga. The assigning of assets among iwi groups have allowed each tribal group to utilise these assets as they see fit, whether by engaging directly with fisheries and industry proceedings, such as Ngāi Tahu; by forming partnerships with local fishery companies to increase quota size and indigenous employment, such as Ngāti Kahungunu; or leasing out quotas to fund tribal activities and development (Hale & Rude, 2017). Such investments have allowed the development of important cultural and social assets such as Marae (traditional meeting houses), language schools, scholarships and employment training (Hale & Rude, 2017). However, as a result of these asset allocations class privilege has become amplified among Māori groups, and is a significant obstacle to further equity (Webster, 2002). Thus, aiming to forge relationships between tribal and urban Māori is a major factor in easing conflict and allowing Māori populations to resist the volatility of political fluctuations. In addition to this, Māori population growth rate along with their enhanced political and economic strength and literacy will continue to work in their favour in the future (Bess, 2001).

Additionally, though Treaty settlement was reached with no further court action, it is important to note that a less than equal partnership still remains between the Crown and Māori. Treaty settlements agreed upon are considered full and final, and therefore no further legal action can be taken by any Māori groups regarding the subject of the settlement, meaning that Māori gain a one-time-only negotiation power in order to allow settlement and after this there are significantly reduced opportunities for Māori to challenge the Crown. The Government thus retains the power of national lawmaking as well as the power of approval of Māori management activities and committees, while Māori remain subjects of the Crown (Memon & Cullen, 1992) and are therefore often required to bend or change traditional processes in order to fit settler colonialist models. One of the main critiques of the QMS is the segregation of fishery activity into commercial, recreational and customary fisheries - a distinction which was never made by the indigenous populations (Hale & Rude, 2017). This, along with the forced structuring of MIO’s (legalised iwi organisations) show the Government’s continued inability to take into account traditional management techniques in preference of laying a settler colonial framework over existing processes. This forcing of hierarchical subordination of hapū to iwi on the basis of a kinship ideology might actually obscure original tribal hierarchies and the reasons for these (Webster, 2002). In fact, in a court ruling it was found that it was the hapū which traditionally held fishing rights, rather than the iwi, and that iwi typically had no rigid structure thus hapū could enter or leave collectives as needs dictated. Therefore, it has been argued that the rights of hapū were in fact infringed by the QMS (Boast, 1999).

Recommendations

Commercial, recreational, and customary fisheries are each managed under different systems in New Zealand, and processes that enable dialogue, collective problem solving, and voluntary tradeoffs between sectors are limited. This has resulted in conflicts over multiple aspects of fisheries management, including where stock biomass targets should be set, how allocations are made in shared fisheries, and solutions to localised depletion (Hale & Rude, 2017). Additionally, because objectives tend to incorporate societal values which may change over time, explicit consideration of whether and how programme objectives can evolve is an important consideration of the system design (Hale & Rude, 2017). Thus, it is essential to set up conflict resolution frameworks and continuous communication networks, as well as giving consideration to ‘living treaties’ which treat interactions as changeable rather than ‘one-time’ agreements.

Secondly, the issue of segregating Māori groups into forcibly defined colonial structures such as MIO’s that are not traditionally recognised should be addressed. Traditionally, there was a flux between tribes and the interactions between whānau, hapū and iwi were complex and changing. This misunderstanding of social structures has led to long term and continuing effects, with the development and exacerbation of Māori elite and colonialised inequality within Māori communities (Boast, 1999; Webster, 2002). Efforts should be made to understand and incorporate genuine traditional social interactions into New Zealand’s development strategy, in a way which matches aspirations of both Māori and the Government.

Additionally, inter-Māori conflict, as has been seen, is a significant issue which needs to be addressed in order to allow Māori to successfully stand up to opposition, such as the Government, in the case of future wrongdoing. Strengthening and protecting the sacred Māori culture is a necessary move and requires the support from all Māori as well as New Zealand society and the Government.

References

Bess, R. (2001). New Zealand's indigenous people and their claims to fisheries resources. Marine Policy, 25(1), 23-32.

Boast, R. P. (1999). Maori fisheries 1986-1998: A reflection. Victoria University of Wellington Law Review, 30(1), 111–134.

Dick, J., Stephenson, J., Kirikiri, R., Moller, H., & Turner, R. (2012). Listening to the tangata kaitiaki: consequences of the loss of abundance and biodiversity in coastal ecosystems in Aotearoa New Zealand. MAI Journal, 1(2), 117-130.

East Otago Taiāpure Management Plan. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.puketeraki.nz/site/puketeraki/files/images/East Otago - Management Plan.pdf

Fisheries Act (1996). New Zealand: Ministry for Primary Industries. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1996/0088/latest/DLM394192.html

Fisheries (East Otago Taiāpure) Order 1999, Pub. L. No. SR 1999/210 (1999). New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/1999/0210/latest/DLM288983.html

Fisheries New Zealand. (2017). Managing customary fisheries. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.govt.nz/law-and-policy/maori-customary-fishing/managing-customary-fisheries/. Accessed March 26, 2019.

Fisheries New Zealand. (2019 a). Quota Management System. Retrieved from https://www.mpi.govt.nz/law-and-policy/legal-overviews/fisheries/quota-management-system/. Accessed March 10, 2019.

Fisheries New Zealand. (2019 b). Customary fisheries management areas. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.govt.nz/law-and-policy/maori-customary-fishing/managing-customary- fisheries/customary-fisheries-management-areas/. Accessed March 26, 2019.

Hale, L. Z. & Rude, J. (eds.). (2017). Learning from New Zealand’s 30 years of experience managing fisheries under a Quota Management System. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, Virginia, USA.

Jackson, A.M., Hepburn, C. D., & Flack, B. (2018). East Otago Taiāpure: sharing the underlying philosophies 26 years on. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 52(4), 577–589.

Lock, K., & Leslie, S. (2007). New Zealand’s quota management system: A history of the first 20 years (Motu working paper 07-02). Wellington.

Mace, P., Sullivan, K., & Cryer, M. (2014). The evolution of New Zealand’s fisheries science and management systems under ITQs. Ices Journal of Marine Science, 71(2), 204-215.

Maori Fisheries Act (2004) New Zealand: Ministry for Primary Industries. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2004/0078/latest/DLM311464.html

Memon, P. A., & Cullen, R. (1992). Fishery policies and their impact on the New Zealand Māori. Marine Resource Economics, 7(3), 153–167.

Ministry for Primary Industries. (2017). East Otago Taiāpure recreational fishing rules. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.govt.nz/dmsdocument/927/

Otago Daily Times (ODT). (2011, October 1). Looking after the fish together. Retrieved from https://www.odt.co.nz/lifestyle/magazine/looking-after-fish-together

Otago Daily Times (ODT). (2010, November 25). Approval of Mātaitai. Retrieved from https://www.odt.co.nz/regions/north-otago/approval-mataitai

Shore, C., & Kawharu, M. (2014). The Crown in New Zealand: Anthropological perspectives on an imagined sovereign. Sites: New Series, 11(1), 17–38.

Statistics New Zealand (2013) 2013 Census QuickStats.

Stewart, J., & Callagher, P. (2011). Quota concentration in the New Zealand fishery: Annual catch entitlement and the small fisher. Marine Policy, 35(5), 631-646.

Treaty of Waitangi (1840). English Version.

Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act (1992). New Zealand: Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1992/0121/latest/whole.html

Treaty of Waitangi Act (1975). New Zealand: Te Puni Kōkiri. Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1975/0114/latest/DLM435368.html

Walrond, C. (2006). Fishing industry - Who owns quota?, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/fishing-industry/page-7. Accessed March 26, 2019.

Webster, S. (2002). Māori Retribalization and Treaty Rights to the New Zealand Fisheries. The Contemporary Pacific, 14(2), 341–376.

| This conservation resource was created by Melle van Heugten & Chufan Cui. Emails: [Melle - lizzy.vanh@gmail.com; Chufan - chufancui520@gmail.com]. It has been viewed over {{#googleanalyticsmetrics: metric=pageviews|page=Course:CONS370/2019/Contemporary fishery management in Aotearoa New Zealand: inter-Maori relations and the government's role in redress|startDate=2006-01-01|endDate=2020-08-21}} times.It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |