Course:CONS200/2021/Endangered basking sharks: will they return to British Columbia's coast?

Introduction to Basking Shark

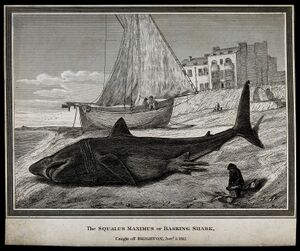

The Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is a seasonal migratory species distributed in the Atlantic, Indo-West and East Pacific Oceans.[1] It migrates to warm oceans. Historically, the Basking Sharks were found in BC water in spring and summer[2] because its population is globally found in marine areas with temperate coastal shelf waters.[3] Moreover, they inhibit the ocean with a high concentration of zooplankton. An analysis of its stomach content confirms they prey on zooplankton since it showed a high concentration of zooplankton in their stomach.[2]

From 1920 to 2007, the population of Basking sharks in the Pacific region has reduced by 90%. [2] Unfortunately, it is not possible to observe Basking Shark in BC waters during spring and summer anymore; the latest confirmed observation of Basking Shark in BC water was back in 1996.[3] The tragedy of population loss is mainly due to human activities: a large and active catching and a federally operated eradication program.[3] Moreover, their biological characteristics have also significantly enhanced the impact of human activities on their population. The Basking Sharks are known to be the species with the most prolonged gestation compared to any animals, which is known to be approximately between 2.6 to 3.5 years.[3]

Unlike the other shark species, the Basking Shark is the most vulnerable species due to human activities. To recover the historical population of the Basking Shark in Canada, the Barking Shark is classified as an endangered species by COSEWIC in 2010 and is protected under the Species at Risk Act.[4]

Future projection of Basking Sharks in BC's Coast.

It has been more than a decade since the Basking Sharks are classified as an endangered species by COSEWIC. Thus, researchers are willing to see them to return to British Columbia's coast. Unfortunately, it is not possible to accurately assess whether the Basking Sharks will return to BC's coast since the accurate assessment of the recovery feasibility of Basking Sharks is complex due to the lack of knowledge on the factors that impact this specific species. And also, they biological features are extremely vulnerable to human activities such as prolonged gestation. However, fortunately, The Species at Risk Act report sees that the recovery status of Basking Sharks in Pacific water is feasible based on the demonstrated progress of the recovery plan.[5]

Human Impacts

The basking sharks feed on zooplankton, and their habitats like headlands, islands, and bays with a strong tidal flow would always contain many planktons.[6] The number of basking sharks used to be abundant in multiple marine areas of British Columbia in history, and the number of collisions between sharks and fishing boats increased between 1940s and 1950s with the expansion of commercial fishing.[7] Over time, the basking sharks were hard to find in the waters of British Columbia as a result of human impacts. On the west coast of Vancouver and in Rivers Inlet, researchers conducted 25 aerial surveys of basking sharks from 2007 to 2011. A Marine aviation survey and a Marine vessel survey were conducted off the west coast of Vancouver Island in 2011 on the Vancouver west coast. However, no basking sharks were found in these surveys.[8]

There were two main reasons why people killed basking sharks. First, the basking sharks have large body sizes and they used to live in the surface waters since their prey are mainly the zooplankton and they have a habit of “basking”.[8] Due to their large size and their living range, they were frequently entangled by the salmon fishing net which caused economic loss to the industry.[7] Therefore they were listed as the "Destructive Pest" in Canadian fisheries.[9] In 1955-1969, due to the federal eradication program, people were encouraged to kill basking sharks,[7] and one measure is that the bows of regional fisheries patrol vessels (the Comox Post) were fitted with sharp cutting blades to pierce and kill basking sharks.[10] An estimation was made that 413 individuals were killed under the eradication program in Canadian waters; 200 to 300 sharks died from the other patrol/eradication methods; 400 to 1500 sharks were killed by entanglement from 1945 to 1970; 50 to 400 individual moralities caused by sport kills which result in about 1000 to 2600 individuals’ death in total.[11]

Apart from the financial loss, the basking shark would have other instrumental values. The liver of basking sharks can be used to produce large amounts of oil, and one shark can yield 200-400 gallons of oil[7]. The economic value of basking sharks was increased and made killing basking sharks more attractive. Thus, the previous major survival threats of basking sharks in BC were the fishing operations of human and boat collisions[2]which significantly decreased basking sharks population. At present, the hunting activities are banned, and the basking sharks are expected to return to British Columbia’s waters. However, basking sharks still experience many threats even if humans do not target them in economic activities. The collisions with marine traffic, coastal development, ecotourism would affect the population which would decrease the number of living basking sharks in BC.[2]

Furthermore, the waters in BC should satisfy some requirements to provide a suitable habitat for basking sharks. To begin with, the habitats should have an adequate concentration of plankton. A minimum prey density for the net energy required of basking sharks was calculated by Sims (1999),[12] which ranged from 0.55 and 0.74 g·m-3. Then, there are requirements for temperature. Basking sharks lived in the area where water temperature is between 8 and 24ºC while most of them were found and recorded in the water of 8 and 14ºC degrees.[13] The basking sharks also have breeding requirements and nursery requirements which means that they need enough space for these behaviors. To conclude, human activities significantly affect the population of basking sharks. In history, basking sharks were killed by the vessels due to the financial loss caused by the entanglement and its increasing economic value. Currently, there are also many threats to sharks like commercial fishing, critical habitats, etc.

Current Remedial Action

In 2010 Canada’s Species at Risk Public Registry [14] listed the pacific basking shark as an Endangered species. This was following an assessment by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada [11] that assessed the species as endangered in 2007. This assessment and listing gave the species legal protection that set the ground for recovery strategies to commence. The Federal government of Canada gives the species protection through the Species at Risk Act which prohibits finning of any shark species. They are also protected through regulations in the Fisheries Ac and over-flights through areas where Basking shark populations have been observed in the past. To establish that the species was indeed endangered SAR conducted aerial and boat-based surveys in the Canadian Pacific waters. Data collected from this exercise was used to create the recovery strategy published in 2011. This recovery strategy was supposed to accomplish the following: (i) retain the current number of the species; (ii) accelerate the population growth; (iii) increase aggregation; (iv) increase basking shark distribution in the Canadian pacific; (v) and increase the breeding pairs to over 1,000 [14]. In 2018, the government through SARA released the Report on the Progress of Recovery Strategy Implementation for the Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) in Canada for the Period 2011 to 2016.[7] That documented what works had been done until then to bring back the species to its Canadian habitats in the Pacific Ocean. In 2008, the Basking Sharks Sightings Network (BSSN) was established to seek public engagement in reporting and documenting sightings of the species in the Canadian Pacific waters. Through BSSN SAR has established an increase in basking shark sightings. 36 sightings were recorded between 1996 and 2011.[14] Beyond recording sightings. BSSN is also used as a promotional vehicle to sensitize the public through banners, printouts, media interviews, oral presentations at community events, and the development of incentive programs to increase reporting of sightings by the public. In 2015 a habitat features modelling study was completed by SAR. According to the progress report, this study was initiated to help increase our understanding of the population structure, abundance, and seasonal distribution within the Canadian pacific waters. This was done using oceanographic data from satellites. The data collected was analyzed to identify the habitat features for Basking sharks in Canada. Moreover, the data was helpful in highlighting what and when different habitat areas are used. For instance, where the species does seasonal feeding, mating, pupping, and rearing[14] vis-à-vis the changing ecology of the Canadian pacific waters. A code of conduct was also developed in 2014 to regulate fishing and boating activities to reduce the number of potential threats to the species. The code aims to achieve among other things the following; reduce mortality and harm during encounters with boats; recommending the best guidelines and practices for helping basking sharks when they are entangled or stranded on shore – in order to increase the chances of survival; and provide guidelines and details for the reporting of sightings to BSSN. Aerial surveys are also used to ensure that these regulations and guidelines are followed within the species’ habitat areas.

Options for Future Remedial Action

Whereas there are ground rules and regulation to control boating and fishing activities in the Canadian pacific to protect basking sharks and increase the population in the next two to three decades, there are no clear guidelines on how fishing activities would be controlled if all over sudden a school of 20 – 30 basking sharks showed up.[15] There is need to create a strategy of how such a scenario would be handled. Halting fishing activities for the entire duration of the sharks activity would be the most ideal course of action. Repercussions of this would be revenue loss. The federal, local, and other involved authorities should create an emergency fund to ensure a soft landing for fishermen and local communities if fishing was to be halted for several days to protect the basking sharks.

Conclusion

The major origin of local basking sharks extinction in BC is mainly due to the fishing industry. At the time of prosperous fishing industry, people killed basking sharks to prevent entanglement which could cause a considerable economic loss. Under the encouragement of federal government with the release of the eradication program, people recklessly killed basking sharks and caused a significant decline in its population. People also saw the benefit of basking sharks in which they can provide large amount of oil production. This further led to the rare population of basking shark. Nowadays, the high density of marine traffic seriously prevents the return of basking sharks. This is because of the possible collisions and pollution where the area is not suitable for basking sharks to inhabit.

Besides human disturbance, Basking shark’s slow maturity rate and population growth have made the recovery process difficult.[16] It takes about 10 -12 years for a basking shark to become sexually mature.[17] Although the decline of basking shark population is mostly human induced, the recovery is hard due to insufficient knowledge of the species. Researchers lack sufficient data collection on basking shark’s habitat requirement, location for reproduction, pupping, and rearing, and population size. This is because basking sharks often dive into deep water where people can’t easily detect and observe them. Basking sharks also foraging over a large range which makes researchers on boat challenging to estimate their population size.[18]

Although basking sharks have already been listed under the Species at Risk Act in 2010, Canada still lacks political action to put effort into the protection plan and recovery plan. There has little research done and not much education delivered to the youth about the local extinction of basking shark. In order to practice in-depth research, researchers need a communication tool which can guide them to accurately identify a basking shark when they spot one on a boat or from the air. In addition, they need a network for reporting collected data and monitoring results. Overall, the urgency of basking shark recovery is not publicly well known due to passive governmental actions and support.

References

- ↑ "ITIS - Report: Cetorhinus maximus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System - Report.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 McFarlane, G. A. (2008). RECOVERY POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT FOR BASKING SHARK IN CANADIAN PACIFIC WATERS. Canada. Department of Fisheries and Oceans.Science, & Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. Ottawa: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Science. pp. pp. 1 - 10.CS1 maint: extra text (link) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":5" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 King, Jackie (16 October 2017). "Chapter Two - Shark Interactions With Directed and Incidental Fisheries in the Northeast Pacific Ocean: Historic and Current Encounters, and Challenges for Shark Conservation". MEDLINE. 78: 9–44 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Basking Shark Pacific population". Government of Canada. 29. Nov. 2011. Retrieved 30. November 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Canadian Government EBook Collection, & Canada. Department of Fisheries and Oceans. (2018). Report on the progress of recovery strategy implementation for the basking shark (cetorhinus maximus) in canada for the period 2011-2016. Ottawa: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. pp. pp. 1- 15. ISBN 9780660268736.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ Government of Canada, (2019, July 30), Basking Shark (Pacific Population), https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/profiles-profils/basking-pelerin-eng.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Government of Canada (November 11, 2018). "Basking Shark". Government of Canada. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Surry, A.M., and King, J.R. 2015. Surveys for Basking Sharks (Cetorhinus maximus) and other pelagic sharks on the Pacific Coast of Canada, 2007 – 2011. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 3108.

- ↑ The Marine Detective, (2011,August 13), Basking in History – The Story of B.C.’s Basking Sharks, https://themarinedetective.com/2011/08/13/basking-in-history-the-story-of-b-c-s-basking-sharks/

- ↑ Wallace, S & Gisborne,B, (2006,December 7). How BC Killed All the Sharks. Retrieved from: https://thetyee.ca/Books/2006/12/07/BaskingSharks/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 COSEWIC (2007). Assessment and Status Report on the Basking Shark (Cetorhinus Maximus) Pacific population in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Vii + 34 p.

- ↑ Sims, D. W. (1999). Threshold foraging behaviour of basking sharks on zooplankton: Life on an energetic knife-edge? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266(1427), 1437–1443. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0798

- ↑ Compagno, L. J. V. (2001). Sharks of the world: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date (Vol. 2). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 SARA. (2011, July). Recovery Strategy for the Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) in Canadian Pacific Waters. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_basking_shark_pacific_0711_e.pdf

- ↑ 9. Pawson, C. (2020, October 12). Researchers hopeful bus-sized sharks will return in abundance to B.C. waters |CBC News. CBC news. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/basking-sharks-bc-recovery-wildlife-1.5758774

- ↑ McFarlane, G. A., Arndt, U. M., & Cooper , E. W. (2011, December 13-15). Proceedings of the First Pacific Shark Workshop. TRAFFIC, Vancouver. Retrieved from https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/9531/first-pacific-shark-workshop.pdf

- ↑ Dagleish, M., Baily, J., Foster, G., Reid, R., & Barley, J. (2010, November ). The First Report of Disease in a Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus). Journal of Comparative Pathology, 143(4), 284-288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2010.02.001

- ↑ Gore , M., Frey, P., Ormond, R., Allan, H., & Gilkes, G. (2016, March 1). Use of Photo-Identification and Mark-Recapture Methodology to Assess Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) Populations. PLoS ONE. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150160

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |