Course:CONS200/2020/Conservation Issues in Northern Kenya

Introduction

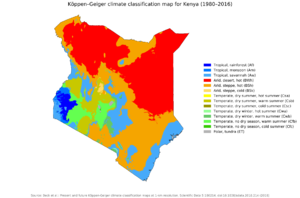

Northern Kenya is a territory located within the East African country of Kenya. Kenya is an expansive country which borders Ethiopia, Somalia, Tanzania, South Sudan and Uganda, as well as the Indian Ocean. While Kenya's climate ranges across the region, it is extremely arid in the Northern territories.[1] As a result of this, wildlife in the North is scattered and infrequent, relative to the rest of the country. What can be found, such as the Somali ostriches, with blue-skinned males, the Grevy’s zebra and reticulated giraffe, is unique and rare.[2]

History of Conservation in Northern Kenya

Historically, national parks and conservation efforts have been associated with gruesome experiences with the ivory trade. "Ivory was bought with blood", at the cost of human suffering, from burnt villages and the destroying of crops to people being kidnapped, starved, and killed.[3] During both world worlds, there was a widespread slaughter of wildlife to feed prisoners of war, and agricultural development started an alienating attitude of regarding all game as vermin, and it was treated as such.[3] Indigenous African groups were displaced from their lands in order to create national parks, and "confrontation with the game laws has sent many of the male to prison - experiences which have solidified the negative attitudes toward wildlife and its conservation".[3] Clearly defined communal land ownership, and the ability to exclude outsiders from using the area under protection with the local people's best interest considered, are necessary for sustainable group-based conservation to occur.[4]

Key Conservation Issues

Poaching

One of the key threats to conservation efforts in Northern Kenya is poaching, where cartels illegally hunt or capture various wild game that are coveted in the black market, often those in Asian nations. An example of this is the African elephant where in 2012, over 70% of recorded deaths of elephants were due to illegal poaching.[6] This has led to many disastrous outcomes, such as leading to the extinction of a species, causing instability in an environment, or by damaging the economy of local communities by stemming cash flow from wildlife tourism.[5] In Kenya, elephant hunting has been banned for more than a period of 40-years, but this has not necessarily led to a reduction in poaching. Given the poverty of much of the population, the high value of ivory, leads individuals to ship elephant tusks overseas for it to be sold on the black market, where the it can, at peak, sell for almost $2,100 US per kilogram in China, where it is coveted as a display of wealth.[7] Despite the fact that Northern Kenya is home to national parks and reserves who work with an aim to protect wildlife, elephant populations are still at risk, an issue worsened by the corruption that has been rampant in the country's officials.[8]

Economic Barriers

Over 80% of Kenya's land mass is classified as arid and semi-arid lands, which suffer tremendously from poverty despite an abundance of natural resources in these regions.[9] The bulk of Kenya's gums and resins are found in the dry land ecosystems in Northern Kenya, however the Gum Arabic supply chain is underdeveloped as this business is relatively new and therefore not well organized.[9] The main economic activities for these regions such as livestock production, small scale farming, and charcoal burning are "often characterized by poor market access, susceptibility to adverse climate conditions, and contribute to the degradation of the environment".[9] Since over the majority of Kenya is comprised of land where the main economic activity is pastoralism, it has led to countless bloody clashes between pastoralists within the region.[9]

Proposed solutions

Conservancies

Wildlife conservancies are portions of land managed by an individual, corporation, or wider community that protects biodiversity in order to enhance the livelihoods of the population. The over-hunting of wild animals is a primary driver of species decline in Northern Kenya.[6] One example of a conservancy in Northern Kenya is the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, which is a sanctuary which focuses on the protection of multiple different endangered species such as the black rhino. Wanjiku Kinuthia, Communications Officer at Lewa, discusses the greatest benefits of conservancies, and how they have succeeded in reducing poaching over the years:

“When we started in 1983, we had just 15 black rhinos living on our land. Not only has this increased but we’ve also been able to re-stock other previously uninhabited areas with rhinos. We’ve reintroduced rhinos to places where they had been wiped out in the 70s and 80s. Lewa’s wildlife isn’t just protected by rangers, and fencing. If anything, what we’ve achieved beyond the fence-line is our biggest success to date; pioneering a community conservation movement across northern Kenya through the establishment of the Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT). NRT, with Lewa as its anchor, is working towards a future where wildlife and people can thrive together.” [10]

In Northern Kenya there has been a particular stress on an increase in community conservancies. This come as a result of the fact that community and private lands support 60% of Africa’s wildlife, and the vital role of local communities in protecting key species is increasingly recognized. The Northern Rangelands Trust, a trust which works with 27 community-led wildlife conservancies in Northern Kenya, published a report in which they state that these community conservancies are responsible for the protection of over 6 million acres, and claim community conservation is an effective means of protecting wildlife.They support this with the evidence that since 2012, elephant poaching has decrease by 35 percent in these conservancies. In fact, in 2014, only 28 elephant mortality cases were recorded as poaching cases, compared to the 49 poaching cases that were reported in 2013.[11]

Panorama suggests four building blocks which when working together provide an efficient and effective solution to community conservancies. These include community partnerships, stakeholder collaboration, science and research, and business leadership.[12] Community partnerships recognizes that the individual communities own and hold the property rights to their land. These individual parcels of land do not make for a productive economy however, when these pockets of land are joined together by communities in order to form a singular conservancy, it becomes feasible for large scale conservation to support extensive populations of wildlife, as well as their habitat. In turn, these populations boost tourism by encouraging people to visit for exclusive safaris and nature expeditions, therefore generating revenue and producing other employment opportunities. It teaches the population of Northern Kenya that their long term benefits are increased by breaking down barriers between communities and collaborating. Stakeholder collaboration focuses on the exchange of information between NGO's, local and national governments and communities. This allows for research to be increasingly more efficient and beneficial to all parties. To ensure this is possible it is important that all stakeholders are treated with respect and understanding, in particular Panorama stresses the importance of not patronizing communities. The third building block is science and research, which discussed the collection of data. Having date on the environment, its history, land use patterns and government policy makes it possible to make informed decisions, to engage the stakeholders. Specific examples of research includes the mapping of movement corridors and migration routes, which aids the creation of conservancy boundaries. Long-term, research is beneficial in displaying positive and negative trends which allows communities to track what is working and what isn't. The final building block focuses on the necessity that is a reliable and stable business environment and the importance of having beneficial investment policies which encourage private sector investments and partnerships.[13]

Savings and Credit Co-operative (SACCO)

One initiative accredited by the UN is the Nasaruni Savings and Credit Co-operative (SACCO), of which there are 1,340 members, which has a focus on assisting communities in their efforts to access market products through loans.[14] According to the United Nations a SACCO pools savings for its members providing them with credit facilities. The predominant objective of a SACCO is to advance its member's economic goals and social security. The co-operatives are an integral part of the Government economic strategy aimed at creating income generating opportunities particularly in the rural areas. Scholars Alila and Obado write that "SACCOs in Kenya are currently a leading source of the co-operative credit for socio-economic development. The phenomenal fast growth of the SACCOs in the last two decades to become a major co-operative type, particularly in Kenya is essentially due to the provision of credit for a wide range of purposes and on relatively very easy terms. The credit has furthermore suited different categories of borrowers including disadvantaged groups, especially women." [15] They highlight that the industry is growing and is expanding into many sectors including accommodation, construction, handicrafts, transport and other small scale industries, by using the statistic that over 45 percent of Kenya’s GDP is contributed to by SACCO initiatives.[15] SACCOs are one of the leading sources of rural finance and in many rural areas the local SACCO is the only provider of financial services. While the exact number of SACCOs operating in Kenya is not known, estimates range from almost 4,000 up to 5,000[16].

It is incredibly beneficial for communities to have a drastic increase in revenue and investment opportunities. Not only do SACCO's serve on an individual health and welfare level, they prove advantageous to conservation schemes. This is because they give local populations the financial means to focus on conservation without compromising their well-being and income. The community is also able to pool together these profits and make collective decisions for higher costing but more effective conservation schemes. These cooperatives assist communities in making use of their land effectively, as an alternative to of depending on agriculture, whether this be for ecotourism or wildlife conservation.[14]

Gum Arabic

A potential solution is the abundance of Acacia Senegal trees, or Gum Arabic in Northern Kenya. Gum Arabic is an under-exploited resource due to its low price, and if given the proper technology and harvesting techniques, it could be a very lucrative market to tap into for Kenyans .[9] This could be a chance to convert pastoralists to harvesters and alleviate some of the existing conflicts, as there is a large international demand for this resource that is not currently being met.[9] However, it is important to recognize that traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) has been used by the local Indigenous peoples to protect Gum Arabic trees, which has been sustainably harvested for generations.[14] The three main conservation strategies used by the locals include restriction to the collection of only dead and fallen wood, community by-laws, and nomadism.[14] Integrating TEK into sustainable conservation and harvesting strategies is evidenced as being useful for maintaining sustainability in the harvesting of Gum Arabic trees, and should therefore be considered in the designing process of such strategies and conservation efforts.[14]

Improved Water Use

Better regulation of water and soil erosion in arid areas of Northern Kenya, applied through a few simple steps such an agroforestry combined with mulching and minimum tillage, can drastically improve water use.[17] Areas of Northern Kenya with higher elevation are better off than lower, drier areas. This is because alpine glaciers in the dry season melt and contribute to water accumulation in rivers and streams.[17] The main problem of Kenya's water depletion takes place in these dry areas where water flow from the alpine does not make it to the low area, or when it does it is contaminated or dirty. Another problem with Northern Kenya's water supply is the land use practices used in agriculture and farming, which in turn leads to runoff water-loss.[17] It is imperative that water is effectively utilized and managed in order to ensure agricultural sustainability in arid regions where pastoralist are not used to dry-land farming. Mulching is an efficient way for farmers to conserve the moisture in the soil and maintain crop growth through dry periods. Mulching, and agroforestry combined with mulching has reduced water loss over time resulting in an increase in plant available soil water and infiltration depth.[17] Mulching is also efficient at maintaining the structural properties of the soil, reducing erosion of soil and conserving water usage. To better conserve Northern Kenya's water levels and quality numerous factors must be fulfilled. Land-use practices must be recorded, socioeconomic aspects of this land-use must be closely monitored, and continued studies on the state of water and soil use in Northern Kenya is a necessity.[17]

References

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Africa - Kenya". Central Intelligence Agency. April 2020.

- ↑ "Northern Kenya". Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lusigi, Walter (1981). "New Approaches to Wildlife Conservation in Kenya". Ambio. Vol. 10: pp. 87-92 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ Greiner, Clemens (2011). "Notes on Land-Based Conflicts in Kenya's Arid Areas". Africa Spectrum. 46: 77–81 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Actman, Jani (February 2019). "Poaching animals, explained". National Geographic.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ihwagi, Festus (2015). "Using Poaching Levels and Elephant Distribution to Assess the Conservation Efficacy of Private, Communal and Government Land in Northern Kenya". PLOS One.

- ↑ "Hope for elephants as ivory prices fall: conservation group". phys.org. March 2017.

- ↑ Anderson, David; Grove, Richard H (25 May 1990). "Conservation in Africa: Peoples, Policies and Practice". Cambridge University Press: 45.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Chretin, M (January 2008). "The Current Situation and Prospects for Gum Arabic in Kenya: A Promising Sector for Pastoralists Living in Arid Lands". International Forestry Review. 10.

- ↑ "Kenya Poaching Stats Out".

- ↑ "Community conservation efforts in northern Kenya reduced elephant poaching by more than a third last year".

- ↑ "Community Partnerships". Panorama. May 2018.

- ↑ Njaga, Daniel. "Community Conservancy model of conservation and income generation for local people".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 "Establishing Community Wildlife Conservancies - Kenya". United Nations Climate Change. April 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Alila, Patrick O; Obado, Paul O (1990). "Co-operative credit: the Kenyan SACCOs in a historical and development perspective". Institute for Development Studies, University of Nairobi.

- ↑ FSD Kenya (2010). "2010 Annual report". FSD Kenya.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Liniger, Hanspeter (November 1992). "Water and Soil Resource Conservation and Utilization on the Northwest Side of Mount Kenya". Mountain Research and Development. 12: 363–373 – via JSTOR.