Course:CONS200/2019/Environmental Implications of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Nature of the Belt and Road Initiative

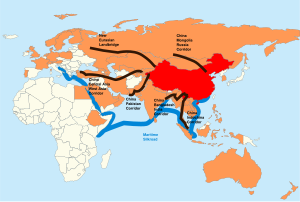

The Belt and Road Initiative is a multi-billion dollar project first announced by the Chinese President, Xi JinPing focusing on strengthening trade, infrastructure, and investment links. This project funded by the Chinese government strives for Chinese economic investments to connect Asia, Europe, and Africa including 71 countries that account for half the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP [1]. Potentially participating countries will account for more than 30% of global GDP, 62% of the world's population, and 75% of known energy reserves.[2]. There is a tremendous amount of economic gain potential for the project that could benefit all countries backing the project.[3].

However, what is not taken into account throughout all this economic benefit is the potential for natural destruction. By taking a simple look outside, we can see how much nature has been altered to benefit the lives of humans. The articles and postings online refer to infrastructure allocated to each country, yet rarely any reference to the ecological damage that would take place from the construction of the Belt and Road Initiative. Not only does the BRI take place on land, but also across international seas. Ultimately, the monetary valuation towards the project appears as if it were to be essential to investors rather than the ecological downfalls to come.

According to the World Bank[4] countries with an overall less GDP will see a slower rate of change in policy reform which could effect the local environment in drastically different ways. Policies that protect the environment would need to be implemented from the beginning as the project will affect ecosystems spanning several continents. However, for the countries with higher overall GDP's they have more potential for both economic growth and environmental conservation policies to be implemented. The remedial actions and recommendations provided give insight into what countries may decide to follow up with in the future.

Categories of Actors

Local Community and Government

Due to the nature of seeking better life quality and eliminating the basic economic problems such as unemployment, low incomes and government supporting rate, poorest developing countries in Southeast Asian, Africa, and Europe that are involved in the Belt and Road Initiative are in imperious demand for the improvement of the economy. For these countries, the most effective way that can lead to economic growth is to actively promote the progress of BRI program through the infrastructure development such as the building of railways, new roads, and new ports. The local communities and governments do gain remarkable benefits economically from infrastructure development as it will decrease the costs of transportation of goods, reduce the time spent for transportation, and attract more investments[5]. As the one who proposed and promoted the BRI program, China benefits the most from this infrastructure development as it not only accelerates the progress of BRI program and increases China’s global influences, but also allows China to import and export more goods with these nations[6]. Therefore, China promised to provide considerable manpower, materials and low-interest debt to nations involved in BRI program to help them make infrastructure development[7]. Since China offered such a huge help and the advantages of infrastructure development are apparently tremendous, most poor countries in the BRI program started unlimited constructions. As consequences, deforestation, the loss of biodiversity, and pollutions happened as results for these unlimited constructions[8]. However, even most local communities and government realized these disadvantages, they kind of chose to ignore them in exchange for economic growth[9].

Global Impacts

Although the poorest developing countries or areas are the most active ones in the BRI program and made most damages to wildlife, as these poor local area gets developed by infrastructure constructions, the action itself intensifies the competition between countries. The nations who spent most funds on infrastructure development received higher GDP or economic growth, in contrast, for the countries didn’t focus on infrastructure development and BRI program, their GDP and economic rarely increased[10]. After most countries involved in BRI realized that issue, in order to keep a positive economy and keep their competitiveness, they have to construct for infrastructure. The environmental implication then expanded from a local issue happened in a few poorest countries to a global issue that made most nations in BRI program have to ignore the ecological damage to pursue economic growth. The deforestation areas for these years in Asian and Europe are mainly located around the new roads or railways that built for BRI program[11]. For the poorest countries, they don’t have any choice since they even cannot feed up all their citizens, and the economic growth for them is a necessity[12]. However, for the nations who are not in immediate demand for economic growth, the competition from BRI program required them to pursue economic growth, as the gaining for other nations sometimes means the loss for neighboring nations[13]. The expanding and the accelerated progress of BRI program brought the competition forward, and the environmental implication from BRI program even affects developed countries, because of the advance of marine transportation, China can enlarge the BRI program to further areas. Therefore, through the increased economic competition between nations involved in BRI program, the environmental issues brought from BRI program gradually developed into a global problem[14].

Environmental Implications

Effects on Biodiversity

Many infrastructures planned and built by BRI are in areas with high environmental value, imposing significant impacts on local biodiversity, exacerbating the loss of biodiversity in regions crossed by BRI economic corridors, such as parts of Southeast Asia and tropical Africa (Fig. 1)

[15].

As key drivers of biodiversity loss, BRI will cross 46 terrestrial and marine biodiversity hotspots or Global 200 ecoregions, 1,739 Important Bird Areas or Key Biodiversity Areas, and many other key conservation areas, such as southeast Asia’s Coral Triangle [16]. According to the spatial analysis conducted by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in recent, the proposed BRI terrestrial corridors overlap with the range of 265 threatened species, including 39 critically endangered and 81 endangered species [17] Therefore, due to its wide range of development, BRI disrupts the ecological niches of many species and creates treats to both local and global biodiversity to a large extent.

The environmental impacts of infrastructures under construction negatively influence biodiversity in many aspects. Roads through natural reserves and remote areas, for example, intensifies the habitat loss and fragmentation by cutting natural habitats into small pieces, increasing the edge effects and providing opportunities for the spread of invasive species[18]. As a result of the building of dozens of new ports, a large amount of roads and power lines are proposed to be built accompanying the inland development [19]. Other negative impacts of road on biodiversity include the increased wildlife mortality, barriers of animal migration, and various kinds of pollution (chemicals, noise, light) [20]. Fires and illegal activities such as poaching and logging will also increase with the construction of roads and other linear infrastructure due to the facilitated access to remote regions [21]

When it comes to the maritime part of BRI, a.k.a. China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative, the increasing sea traffic for trading purpose facilitates the spread of invasive species and pollution between countries [22] [23]. The disastrous consequences of BRI for biodiversity may takes years to decades to show [24]

Moreover, protected areas along the BRI corridors also suffer the risk of degradation, downsizing and being deprived of legal protection, in order to facilitate the access and use of natural resources [25] [26]

Effects of the Exploration of Natural Resources

To support the construction of BRI infrastructures, a wide range of raw materials and natural resources, such as fossil fuels and sand and limestone for the production of concrete and cement, will be excessively extracted [27] (Lechner & Chan, 2018). The extraction rate of sand, for example, has already exceeded its natural renewal rate, resulting in the eroding of river edges and deltas, and severely affecting coastal and marine ecosystems [28].

Furthermore, the large investment in pipeline infrastructure will accelerate the exploitation of oil and gas reserves [29], enhancing the dependency of the world on fossil-fuels and hindering the development and promotion of renewable energy sources [30]. Overall, the expansion of transportation and power networks will exacerbate the overexploitation of resources and resulting in the degradation of surrounding landscapes [31].

The Relocation of Pollution

As the China’s Belt and Road Initiative is now explicitly supporting Chinese companies to move excess capacity abroad, the Chinese Government is transferring the environmental cost of economic development to other countries participating in the program [32]. The essence of such a transfer is a relocation of pollution, as the construction of transport and energy infrastructure is said “to create an important foundation for the transfer of low-value added labor-intensive industries from China” [33]. Nevertheless, many regional and international environmental non-governmental organizations have showed their concerns to such a relocation, which enables China to become more ecofriendly by relocating pollutive productions or unsustainable resource extracting practices to less developed countries [34].

Example of Tajikistan

As one of the poorest countries of the former Soviet states, Tajikistan de-industrialized after the Soviet collapse and almost half of its GDP relies on remittances from Russia [35]. The undeveloped economy of Tajikistan makes it a suitable choice along the Silk Road (BRI) for China to relocate its cement industry, which is extremely harmful for environment and overproduced. In 2011 China’s, Huaxin Cement company signed an agreement with Tajikistan to build a cement plant with the capacity of 1.2 million ton per annum (mta) near the capital, Dushanbe. In March 2016, Huaxin opened its second 1.2 mta plant in northern Tajikistan.In addition, a joint venture between a private Zhejiang producer and Tajik Cement opened a 60 mta cement production facility in 2015, with the potential to expand to 1.5 million tons per annum [36]. Since 2010, the production of cement in Tajikistan has multiplied five times, whereas environmental regulations and governance have remained weak and corrupt, making it difficult to monitor these enterprises’ adherence to environmental standards [37]

Options for remedial action(s)

Local and Global Policy

The negative externalities from the project that would directly affect local communities rather than larger more powerful countries could be negated by the proper implementation of local and global policy. If implemented it would protect the local communities and they would even see future benefits from the project. Instead of having the infrastructure travel directly through these communities, if governments would support the local infrastructures through policies ensuring that proper technology would be created for a safer and cleaner future it would work. The introduction of the local policies could therefore influence larger countries with a stronger input on the program forcing them to cohesively collaborate for the success of the project. Essentially, not only would policies protect ecosystems, they would be housing for future conservation technology that would ensure both the economic and ecological growth of communities and countries.

Payment for Ecosystem Services

With the project spanning across several continents and over 70 countries, if governments implement a payment for ecosystem service as simple as international development companies paying for and contributing money into ensuring the ecosystem is not damaged, it would set precedent for following countries and governments to do so as well. Not only would this benefit the local government, but it also would raise awareness towards conservation on a project as big as the Belt and Road Initiative.

Non-Governmental Organizations

Non-governmental organizations encompass a potential foundation that could potentially strive towards educating communities to understanding the importance of their ecological communities. They are especially significant given the lack of support from the government and the limited media coverage of the potential environmental outcomes of the Belt and Road Initiative. Based on most media coverage for the project, they all cover one main idea of an economic boom from the success of the project. However, what they fail to cover is the environmental downfall that local communities will likely face due to the sheer size of this project. NGOs from these local communities have proper resources, connections, and experience in order to communicate desired messages from those educated of the environmental implications and putting it into policy goals and public education.

Recommendations

Governments enforcing harsher regulations and penalties on over-extraction of natural resources will prevent exceeding the natural renewal rate of raw materials. This will protect coastal and marine ecosystems as well as the biodiversity in these areas. Financial institutions and governments of different countries involved in the funding of BRI must take initiative to ensure each project comply with environmentally sustainable conditions. By having control of the loans this allows them to enforce environmental standards upon each project. This allows the BRI project to be designed and implemented with respect to environmental protection and preservation. Governments of countries taking part in the BRI project plays a crucial role in prosecuting those who misuse this infrastructure. These new roads built can be exploited by poachers and illegal logging companies, gaining access to untapped resources. Governments and local communities must oppose such actions and take legal prosecution to those to choose to participate. China’s role in easing the environmental impacts of the BRI is imperative, although the Chinese government cannot closely oversee all aspects of the project on a local scale. They can support local governments financially, in helping them enforce such regulations. The BRI project is still currently ongoing and planning. There must be more emphasis on the importance of addressing all environmental impacts before allowing infrastructures to be built. Well-planned road developments are able to support environmental conservation by causing less environmental degradation and negative impacts on protected areas. Well-planned roads can also benefit local communities and agriculture. Ultimately, Local communities can be linked to larger cities and allow for more accessible resources to schools and hospitals. Further allowing knowledge to be supplied through the BRI initiative will create a stronger understanding for Conservation as a whole.

Conclusion

There is a clear correlation between the large scale that the Belt and Road Initiative and the degradation of the environment have on one another. There has been numerous published scientific reports stating the vast amount of potentially negative factors brought upon by the Belt and Road Initiative. Furthermore, we have been able to clearly present the negative effects of the project, which include but are not limited to the Effects of the Exploration and Exploitation of Natural Resources, The Relocation of Pollution, and Effects on Biodiversity.

Ultimately, many arguments are for the further development of the Belt and Road Initiative implemented by China, which support deforestation, reduced biodiversity, and the destruction of habitat. Furthermore, the scientific evidence backed reports, merely cover the economic development factors, rather than sharing a focus on environmental benefits/downfalls. Essentially, the Belt and Road Initiative project needs more future development plans focusing on benefiting the ecosystems directly involved to maintain further environmental growth potential.

References

- ↑ Kuo, L., Kommenda, N. (2018). What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?. Retrieved April 06, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/ng-interactive/2018/jul/30/what-china-belt-road-initiative-silk-road-explainer

- ↑ (2018, March 29). Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved April 1, 2019, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative

- ↑ (2018, March 29). Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved April 1, 2019, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative

- ↑ (2018, March 29). Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved April 1, 2019, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative

- ↑ Ascensão, F., Fahrig, L., Clevenger, A.P., Corlett, R.T., Jaeger, J.A.G., Laurance, W.F., Pereira, H.M. (2018). Environmental challenges for the Belt and Road Initiative. Nature Sustainability, 1(5), 206-9

- ↑ Fister, S. (2017). Win-win cooperation along the 'One Belt One Road'. Retrieved from Jan 28, 2019

- ↑ Fister, S. (2017). Win-win cooperation along the 'One Belt One Road'. Retrieved from Jan 28, 2019

- ↑ Fister, S. (2017). Win-win cooperation along the 'One Belt One Road'. Retrieved from Jan 28, 2019

- ↑ Losos, E., Pfaff, A., Olander, L. (2019). The deforestation risks of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from February 20, 2019

- ↑ Fister, S. (2017). Win-win cooperation along the 'One Belt One Road'. Retrieved from Jan 28, 2019

- ↑ Losos, E., Pfaff, A., Olander, L. (2019). The deforestation risks of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from February 20, 2019

- ↑ Ruta, M. (2018). Three Opportunities and Three Risks of the Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from March 6, 2019

- ↑ Ruta, M. (2018). Three Opportunities and Three Risks of the Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved from March 6, 2019

- ↑ Ascensão, F., Fahrig, L., Clevenger, A.P., Corlett, R.T., Jaeger, J.A.G., Laurance, W.F., Pereira, H.M. (2018). Environmental challenges for the Belt and Road Initiative. Nature Sustainability, 1(5), 206-9

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Van Der Ree, R., Smith, D. J., & Grilo, C. (2015). Handbook of road ecology. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Leadley, P., Proença, V., Fernández-Manjarrés, J., Pereira, H. M., Alkemade, R., Biggs, R., ... & Gilman, E. (2014). Interacting regional-scale regime shifts for biodiversity and ecosystem services. BioScience, 64(8), 665-679.

- ↑ Van Der Ree, R., Smith, D. J., & Grilo, C. (2015). Handbook of road ecology. John Wiley & Sons

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Laurance, W. F., Goosem, M., & Laurance, S. G. (2009). Impacts of roads and linear clearings on tropical forests. Trends in ecology & evolution, 24(12), 659-669.

- ↑ Leadley, P., Proença, V., Fernández-Manjarrés, J., Pereira, H. M., Alkemade, R., Biggs, R., ... & Gilman, E. (2014). Interacting regional-scale regime shifts for biodiversity and ecosystem services. BioScience, 64(8), 665-679.

- ↑ Li, N. & Shvarts, E. Te Belt and Road Initiative: WWF Recommendations and Spatial Analysis Briefing Paper (WWF, 2017); https://go.nature.com/2v3SwoG.

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Mascia, M. B., Pailler, S., Krithivasan, R., Roshchanka, V., Burns, D., Mlotha, M. J., ... & Peng, N. (2014). Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD) in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, 1900–2010. Biological Conservation, 169, 355-361.

- ↑ Watson, J. E., Dudley, N., Segan, D. B., & Hockings, M. (2014). The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature, 515(7525), 67.

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Torres, A., Brandt, J., Lear, K., & Liu, J. (2017). A looming tragedy of the sand commons. Science, 357(6355), 970-971.

- ↑ Liu, D., Yamaguchi, K., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Understanding the motivations behind the Myanmar-China energy pipeline: Multiple streams and energy politics in China. Energy Policy, 107, 403-412.

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Lechner, A. M., Chan, F. K. S., & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Biodiversity conservation should be a core value of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nature ecology & evolution, 2(3), 408.

- ↑ Elena F. Tracy, Evgeny Shvarts, Eugene Simonov & Mikhail Babenko (2017) China’s new Eurasian ambitions: the environmental risks of the Silk Road Economic Belt, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58:1, 56-88, DOI: 10.1080/15387216.2017.1295876

- ↑ Lu, Yue. 2016. “One Belt One Road: Breakthrough for China’s Global Value Chain Upgrading.”IPP Review, April 23. Accessed August 3, 2016. http://ippreview.com/index.php/Home/Blog/single/id/113.html

- ↑ Elena F. Tracy, Evgeny Shvarts, Eugene Simonov & Mikhail Babenko (2017) China’s new Eurasian ambitions: the environmental risks of the Silk Road Economic Belt, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58:1, 56-88, DOI: 10.1080/15387216.2017.1295876

- ↑ Elena F. Tracy, Evgeny Shvarts, Eugene Simonov & Mikhail Babenko (2017) China’s new Eurasian ambitions: the environmental risks of the Silk Road Economic Belt, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58:1, 56-88, DOI: 10.1080/15387216.2017.1295876

- ↑ Elena F. Tracy, Evgeny Shvarts, Eugene Simonov & Mikhail Babenko (2017) China’s new Eurasian ambitions: the environmental risks of the Silk Road Economic Belt, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58:1, 56-88, DOI: 10.1080/15387216.2017.1295876

- ↑ Van der Kley, D. 2016. “China Shifts Polluting Cement to Tajikistan.” China Dialogue, August 8. Accessed November 27, 2016. https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9174- China-shifts-polluting-cement-to-Tajikistan

| This conservation resource was created by Will. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |