Course:ASIA355/2023/The Story of Qiu Ju: Between Bureaucracy, Legality and Queer Femininity

The Story of Qiu Ju: Between Bureaucratic Worlds, Legality and Queer Femininity

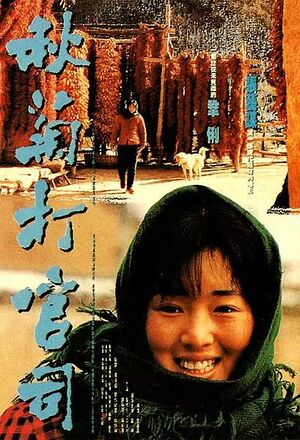

Based upon Zhang Yimou's 1992 film The Story of Qiu Ju (Chinese: 秋菊打官司; "Qiu Ju goes to court").

Group Members' Contributions

| Contributor(s) | |

|---|---|

| Introduction | FB, JH, QM, RL |

| Stories Behind the Film | JH |

| Histories of the Film's Reception | JH |

| Scholarly Literature Review | RL, QM* |

| Comparative Analysis | FB |

| Alternative Interpretation | QM |

| Conclusion | FB, JH, QM, RL |

| * signifies minor contributor

| |

Introduction

Synopsis

A comedy-drama, Zhang Yimou's The Story of Qiu Ju (1992) starts with an incident that occurs in a northwest village in 1990s China. This is where our protagonist's—Qiu Ju—husband, namely Qinglai, is assaulted by the village chief Wang, thus inciting her to seek justice from China's newly formed legal system. After repeated futile attempts to acquire satisfactory legal redress, the two opposing parties find themselves compromised after Wang helped deliver Qiu Ju's baby. Still, at the end, with the newfound evidence of Qinglai's broken ribs, Wang was detained, causing Qiu Ju to question the meaning of her quest towards self-justice. Starring Gong Li as Qiu Ju, Kesheng Lei as village chief Wang, Liu Peiqi as Qinglai, Liuchun Yang as Qinglai's sister, the film premiered on August 31, 1992 in China [1][2].

Roadmap

To begin, our stories behind the film will zoom in on director Zhang Yimou's life through his various interviews, so as to understand the intrinsic behind-the-scene details of The Story of Qiu Ju during the unmatured justice system in 1990s China. Then we will explore the different receptions on the film through various media sites and news article as well as through modern film reviewers.

Then, the scholarly literature reviews covers three articles which analyze the film's themes on legality and self-legitimacy. Overall, according to three articles, there is an underlying disconnect between rural justice and the modernist legal system in 1990s China.

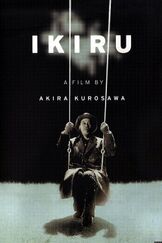

Proceeding on, in our comparative analysis, we set out to compare The Story of Qiu Ju with a Japanese film by director Akira Kurosawa, Ikiru, deriving an argument on the nature and presentation of bureaucracy. By comparing and contrasting similarities and differences between these two films, we hope to bring new context and understanding to the analysis of The Story of Qiu Ju.

Lastly, the alternative interpretation conveys how the narrative is not so much construed by abstract conception of justice—between public, bureaucratic legality or private self-legitimacy—but moreso by Qiu Ju’s femininity that queers China’s modernist project and the masculine phallic.

Stories Behind the Film

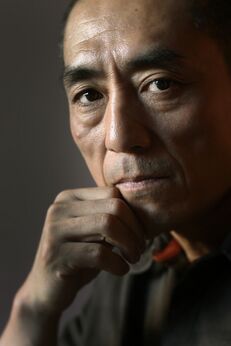

Zhang Yimou’s Background and Awards [3]

In Zhang Yimou’s film, many villages and rural areas were depicted. Zhang Yimou was born in Xi’an, Shan Xi on April 2, 1950 [2]. After graduating from high school in 1986, he went to work in the countryside of Qianxin County, Shanxi Province, then he became a factory worker for a cotton factory in Xianyang City [3]. In the film, many of the real life details are composed from Zhang’s life, the perspective of a low class familyhood in the countryside. Since Zhang did not have a deep understanding of the life of the farmers in the south, he situated the film in the Shanxi countryside. Because Zhang was born as a peasant farmer in Shanxi, he became integrated with the folk customs of Shanxi and has gained knowledge of the rural living habits that existed in post-socialist China [3].

The film was released in China on August 31, 1992 [1]. In 1992, it won the Golden Lion Award at the 49th Venice International festival in Italy [3]. In 1993, it won the Best Feature Film and Best Actress Award at the 13th Golden Rooster award, as well as the 15th Popular Film Hundred Flowers Award [2][4].

Goals of Filming [5]

Zhang Yimou, who had recently filmed Red Sorghum, Raise the Red Lantern, and Ju Dou, believed that when compared to Taiwanese directors, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang, mainland directors—including himself—hadn't zoomed in that much on the people [5]. He hoped directing The Story of Qiu Ju would serve as a remedial effort to emphasize more on the people's perspective. He also mentioned how there were many narrative weaknesses in his past work, thus deliberately directing The Story of Qiu Ju to hone his narration ability [5].

Before and After Making The Story of Qiu Ju [6]

Zhang was to, supposedly, began filming Liu Zhengyun’s Ground Covered With Chicken Feathers [6]. But in 1991, he saw the opening chapter of The Wan’s Family’s Lawsuit by Chen Yuanbing [6]. This immediately changed his mind, and he shifted towards producing Chen Yuanbing’s novella. The Story of Qiu Ju thus was adapted from The Wan’s Family’s Lawsuit [6]. Liu Zhengyun was the most influential writer during that time, while Chen Yuanbing was not well known for his name [6]. Why did Zhang, so bluntly and quickly, change his mind? He claimed this to be an intuitive decision [6].

There was also another problem prior to shooting. Liu Heng was supposed to be the scriptwriter for The Story of Qiu Ju Yet, Zhang rejected Liu Heng’s script [6]. He realized the original script was very dramatic and the ups and downs of the plot were very detailed, thus overcomplicating the shooting [6]. Zhang therefore abandoned Liu Heng’s script and switched to a more documentarian shooting for the film.

Process of Filming “Candid Shots” [7]

According to his interview, because Zhang rushingly chose to shoot this film in a documentarian style, without using Liu Heng’s original script, he worried about the stylistic outcome of the film for a period of time [6]. Then, one method to make the film more documentarian was specifically used, that is: Zhang Yimou's proposal to use “candid shots”. This idea enlightened the photographer Chi Xiaoning, who then utilized a Super 16mm camera in production, which is famed for its literal capture of objects [6]. Zhang Yimou joked on stage that he was the first “candid shot master,” much preceding today's prevalent use of Super 16mm by the paparazzi [7].

With the new tiny 16mm camera, Zhang Yimou was able to take shots lasting around 11 minutes long [7]. As a director, he would snuck the camera into places at 4 or 5 in the morning and he would create two holes, hid the photographer in every place in the village he could find to film [7]. When the actors came, they would wear the crops and makeup and walk through places with the hidden cameras [7]. Even when they weren’t filming, they would hold the camera in front of dogs, oxen, and people, eventually no one would be surprised by the camera anymore [7]. He said that filming laws were very different compared to now. Nowadays, Zhang said it's very much impossible to make a large-scale candid shot filming on the street, because it would be violative of people’s privacy [7].

Histories of the Film’s Reception

First Civil Right Lawsuit Against a Filmic Portrayal [8]

The Story of Qiu Ju was a film to give people knowledge about the legal system, though, ironically the film received many backlash regarding legal implications itself. The film was sued by Jia Guihua, an elderly woman who was eating cotton candies in the film. This became the first lawsuit since the founding of the People’s Republic of China on the rights of filmic portrayal [8].

In 1993, Jia Guohua, a retired female worker from the construction company in Baoji city, Shanxi province, filed a portrait right infringement lawsuit with the People's Court of Haidian [8]. She sued the Beijing Film Academy and Youth Film Studio due to her portrayal in The Story of Qiu Ju [8].

Due to her presence in the film, in the second year of the film’s release, there were many people asking her how much she earned from appearing in the film [8]. Some people also lambasted her physical appearance in the movie, telling her she was ugly [8]. This hurt Jia Guohua and emotionally traumatized her. In 1984, she said that she suffered small pox when she was young, this scarred her face, so she had to always cover it with a pair of sunglasses and never wanted to take pictures[8]. She never thought that she would gain such publicity through a movie, and would be called ugly [8]. A lawsuit thus was raised, requesting to delete her portrayal in The Story of Qiu Ju, and to compensate her emotional trauma with 8000 yuan and economic loss with 4,720.78 yuan [8].

Many lawsuits on portrayal rights increased in the 1980s due to this incident [8]. For example, the actor Yang Zaibo sued a magazine for using his portraits in advertisements, and a Rockstar named Cui Jian sued a publishing company for unauthorized use of his photos for book cover [8]. Due to this, in April 1986, the National People’s Congress passed the first comprehensive civil code after founding the PRC, detailing many general principles of civil laws in the nationstate [8]. Article 100, specifically, stipulates that film producers are required to be gain ordinary people's consent in order to portray them in films for commercial purposes[8].

Clearly, in The Story of Qiu Ju, Jia Guihua’s image was only used to delineate the life of a normal Chinese citizen in the city. In addition, the shot only carried on for 4 seconds and there were no clear malicious intentions, nor did the film exaggerate any of Jia Guihua's physical imperfections. Still, many would argue that Jia Guihua was the first ordinary Chinese who consciously used her legal rights—just like Qiu Ju—to further increase the respect and protection of civil rights in China. Then, in an ironic way, The Story of Qiu Ju was indispensable in the configuration of the legal civilities in modern China.

A Standout in Fifth Generation Cinema [9]

A part of the Fifth Generation Cinema, as mentioned, this film is unique in its documentarian style and portrayal of legality. Situated post-Tiananmen Protests and intense economic reforms, this style allows the film to step down from the forced aesthetics and philosophy of many films belonged to socialist realism prior, and deal with critical and relevant social issues such as self-justice and rural governance which permeates early post-socialist China, signifying the nation's uneasy, transitory period [9]. The film also continues the Fifth Generation Cinema through depicting traditional and rural life in China with an epic, enthusiastic and anthropocentric lens [9]. Still, though, The Story of Qiu Ju is able to separate itself from many of its cinematic 'peers'. One must then compare The Story of Qiu Ju to Yellow Earth by Chen Kaige. While Yellow Earth's depiction of rural life merely serves as a critique towards the PRC through the characters' impoverished lives, The Story of Qiu Ju, on the other hand, acts as a reflective response to the political structure of traditionalism in post-socialist China [9]. In truth, The Story of Qiu Ju's village and rural life are beings in themselves, independently existing and not instrumental to any causes. While earlier Fifth Generation Cinema centers on the country's backwardness, The Story of Qiu Ju's rural landscape is fruitful with an abundance of life, sustenance and persistence [9]. One example is Qiu Ju family's chili peppers business. Not only a necessity or a food source, the chilies symbolize the manual labor of rural life, portraying moral dignity, rebelliousness and resistance of Chinese farmers against historical hardships [9].

Critiques Through Different Cultures

Chicago Reader's Jonathan Rosenbaum says that “the film’s integrity is chiefly a matter of countless small and uncommon observations” [10]. He states that The Story of Qiu Ju is a comedy film that thematically centers on bureaucratic negotiations. The film showcases much more of China's dimensionality than what Zhang’s other films have up to date [10].

Roger Ebert from Chicago Sun-Times notes that this movie style seems to be inspired by postwar Italian neorealism [11]. He says that there is a point in the film where it begins to seem repetitive: the leader will remain unbending, Qiu Ju will keep appealing [11]. This repetitiveness connects to the rhythm of the village life, the relationships of friends and family, and the approaching of the birth of Qiu Ju’s child [11]. The heroine's stubbornness also seems to be an exaggerated. Albeit a comedy-drama film on the lives of ordinary people, if The Story of Qiu Ju were to be made in America, it would most likely be rendered way more comedic [11].

Some compliment on the usage of the film's documentarian style. Jonathan D.Spence from the The New York Review of Books says that “This is the first film I have seen from China that has at once such documentary verisimilitude, such comic inventiveness, and such reflective strength." [12] While other critics condemn such documentary style as a demure and objective portrayal of Chinese rural lives, such as Rita Kempaley from the Washington Post, who thinks that the documentary style makes the film too litigious and not as entertaining as it seems [13].

Comparing different film critic sites, whether Western or Eastern-centered, Eastern film critic sites such as Douban, Maoyan have a higher rating than Western film critic sites such as Rotten Tomatoes and IMDb, though similarly positively reviewed. Statistics show that Eastern sites have a combined average ratings of 7.95, with 92% of people recommending the film [14][15]. While the Western sites have an average of 7.6, with an average of 86% people recommending the film, a slightly lower number [1][16]. This could be due to the film's competition with high-budget Hollywood films and the general lack of translative cross-cultural understanding between Western audience and the film. Although the film was criticized for its copyright disputes as well as infringement lawsuits, this didn't deter The Story of Qiu Ju from attaining high domestic box-office performance. Domestically, the box office was 58,000 yuan and, globally, it grossed to over 1.89 million US dollars, making this film one of the top ten most commercially lucrative films in China (box office statistics are as of June 18, 2023). [17][18]

General Perception and The Film’s Televised Version

The film received generally positive reviews, with most people commending it on its thematic concerns of legality versus self-legitimacy [9][1][16]. The film itself elucidates on modernist 1990s China’s justice system, where many critics affirm that without The Story of Qiu Ju, we would not become aware of the formalist themes of modernity versus tradition, and city vs countryside [9][19][20]. While, for some, the film serves as a critique of China’s flawed justice system, it can also be read as an acknowledgement of Chinese government, as it does portray the system as restorative and compensatory in some ways [9][21].

Being one of Zhang Yimou’s proudest works, perhaps people can question whether this film made Zhang Yimou famous. One renowned television series, namely The Story of Xing Fu (2022), has achieved good ratings since its first release. Funny enough, this is supposed to be the TV version of The Story of Qiu Ju, as it's based on the novella The Wan’s Family’s Lawsuit [22]. Despite this, to accommodate to the trends of commercialist shows, The Story of Xing Fu dramatized the original plot with many newly added obstacles to the main character Xingfu, or Qiu Ju, thus making the plot seem more illogical [22]. This reflects on the two different periods of film-television making, where modernist 1990s China’s filmic works have more social realist components, while post-socialist China’s works seem to be imbued with dramatic spectacles.

Scholarly Literature Review

Between Singularity and Repetition [19]

Xudong Zhang opens up his book chapter on The Story of Qiu Ju ("Narrative, Culture and Legitimacy") by providing some background knowledge about the renowned filmmaker, Zhang Yimou. He explains how as an autuer, Zhang Yimou was able to create a signature visual style that underlies all of his films.

Moving on, Xudong explores the intermingling between cultural politics and everyday lives in a rural environment. Xudong explains how the stylistic choice of the film, a documentary style, allowed the film to explore the interactions between rural justice and government, and the growth of legality in China [19]. Another significant aspect of the film that Xudong identifies is how Zhang Yimou portrays rural life as a being-in-itself rather than a visual aesthetic for the film. He likens the state of rural life in the film to the red chili peppers in the film, where when hung outside to dry; it becomes a self-sufficient form. The cinematography in the opening captures the sense of a more objective view and helps to place the protagonist directly into the film world. Due to a lack of clear messaging regarding the conflict between government and society, Xudong argues that critics who binarily view the film as being a government shill are missing the point[19]. Zhang Yimou seemingly humanizes the state by making the secondary characters of the film, the policeman and director of the city’s Public Security bureau, act as irresolute mediators in a tumultuous society which is undergoing major change instead of portraying them as cogs in a machine.

The next subject that Xudong explores through analysis of the film is legality and legitimacy which are the two subjects underpinning the protagonist’s motivation. First of all, Xudong clarifies a mistranslation in the film regarding the phrase, shuofa. In the film’s translation, shuofa was translated as either justice or apology interchangeably, but Xudong argues that a more comparable translation in Enlglish for shuofa would be “explanation” [19]. So, what Qiu Ju is seeking in the film is not an apology or justice, but rather an explanation. Xudong explains how the character is not motivated by legality or even justice but rather to legitimize the thoughts running through her mind [19]. In essence, what Qiu Ju is looking for is someone to validate her existence and identity in society and to make the world make sense to her by reaffirming her thoughts. What Qiu Ju seeks is something beyond law at its highest level which is not written code, but rather the moral and political constitution behind legal coding which is why she will always fail to get a satisfactory answer. In a way, both society and the state have failed each other in this instance. The peasant fails the state by not understanding the effort that the state has put into modernizing the legal system which protects and upholds their human rights, and the state fails to capture the moral reality of the sovereignty of society. To conclude, it is not that the legal system is not modern or modern enough, but that the legal system fails to understand the singularity of the peasants and their unwritten laws.

For Xudong’s final analysis of the film he analyzes the repetition and singularity in the film. In his analysis of singularity, he brings up the difference in technology and legality between the rural village and the city. The cityfolk and state are living with technology and legal processes that postdate the peasants, and this causes a disconnect between the two. Xudong agrees to the notion of a disconnect by explaining how the state’s legal justice does not work for peasants like Qiu Ju in the real world [19]. Peasants are only able to follow this new technology and new legal processes in the state by means of imitation, so they do not have a deep understanding of what is going on. Xudong then discusses repetition, the narrative device of the film. He states that repetition is useful in the self-affirmation of one’s own identity and that it is useful in figuring out if something may be missing in the system, when Qiu Ju repetitively goes to the system for an answer but comes up empty-handed [19].

Reimagining Legal Absolutism through Private Justice [20]

In their article "Relating Cinematic Art to Juridical Reality", Fiona Sze Lorrain explores the relationship between the legality practiced in the film and legal practices in real life. Fiona provides us with the setting and timeframe of the film, which is one that occurs in a rural village in a post-Tiananmen era where new legal practices have been put in place in order to modernize the legal system. However, the legal absolutism of the legal coding does not always provide the most satisfactory answer or justice as Qiu Ju pursues higher and higher courts to be given the same result.

Regarding the conflict, Fiona explains that there were breaches from both parties of Qiu Ju’s husband and the village chief. Fiona uses Turner’s definition of a breach which is a broken rule in a public setting [20]. Afterwards, the constable who arrives to the situation attempts mediation. Fiona then explains the reasoning for why Qiu Ju demands to seek higher courts following this encounter, as the concepts of fault and responsibility are foreign to mediation. In mediation they simply seek resolution and not the truth in totality regarding the incident. Because Constable Li has authority over the situation, there is doubt whether mediation will truly work as true mediation requires two things; impartiality and equidistance [20]. It requires impartiality from the mediator themself, and the ability to not be coerced by external factors, and it requires an equidistance between the individual parties being mediated which means that either party cannot be coerced by the other. As Constable Li has more authority than Chief Wang, he cannot be seen as impartial as he holds power. When Chief Wang acts in a demeaning manner towards Qiu Ju and refuses to give her the explanation she wants, Qiu Ju ascends the judicial ladder in search of an answer. Qiu Ju is now testing the newly made judicial system of post-Tiananmen China.

Fiona describes Qiu Ju as a relational litigant which is one that is concerned heavily with status and social relationships [20]. As a peasant, Qiu Ju is not concerned with legal principles and rulings and more focused on statuses and social relationship. One example Fiona provides is when Qiu Ju questions whether the officers are conspiring with one another as they have higher authority and status than her. The majority of the cast falls within the label of rule-oriented litigants which are people who solely follow the legal code without a thought given to social statuses.

Fiona identifies the gap between legality and justice when Qiu Ju is unable to give the court a response to the question of the definition of justice. This is due to the fact that justice is an abstract concept, so something that is firm like written legal codes cannot truly encompass the concept.

Later on, when Qiu Ju witnesses the execution of a convicted murderer, her lack of social experience in society imparts her with the notion that the law is powerful and that law itself is a construct of power. Fiona then explains how Zhang Yimou may have seen public punishments through the same lens as Michel Foucault [20]. This view is that public punishments were more theatrical in nature than they should’ve been. To add on, Fiona lays out how Zhang Yimou views the decaptiation as an allegory to Chinese society [20]. It shows how post-Tiananmen China has become a headless country with its citizens spectating with a spiritual deficiency [20].

At the end of the film, when Chief Wang is punished for his crimes with a jail sentence, it reaffirms the thought that legal principles and the legal systems are less concerned with the well-being of its citizens, but rather only have knowledge of punishment.

China's Particularistic Moral-Cultural Codes [21]

A-chin Hsiau's "The Moral Dilemma of China's Modernization" favors the reading of China’s particularistic moral-cultural codes over Western universal egalitarianism that many other scholars favor upon analyzing The Story of Qiu Ju [21]. Hsiao presents a nuanced standpoint on the film, subverting other scholars’ condemnation of the Chinese legal system as the film’s main critique. Instead to him, the bureaucratic delay in responding to Qiu Ju’s request for justice is not a critique of 1990s China’s lack of reservation for individual dignity and rights. Moreso, to Hsiau, the problem resides on the gap between legality and self-legitimacy, where Qiu Ju’s moral code and particularistic conception of what justice is, are inverse to the modern justice system’s universal ideals [21].

Hsiau argues this by critiquing scholars’ Western liberalism as narrow in its approach to the Chinese self and interpersonal relationships. He analyzes Qiu Ju’s conflicted relationship with the village chief and her persistent court-going, that there is an inherent difference between Chinese traditionalism and Western liberalism, which other scholars don’t try to conceive [21]. This difference manifests into different conceptions of selfhood, where Qiu Ju represents the Chinese self, inseparable from social context. While to the West, conversely, the legal system—as a neutral network—helps mediate between independent selves. Thus, comparing their Western legal ideals with the ones portrayed in the film, scholars project liberalism into their critique of The Story of Qiu Ju without nuance, biasedly deeming the Chinese legal system as inefficient and fraught with legal loopholes [21].

Therefore, to Hsiau, Qiu Ju is perfectly justified in her resolution with the village chief over his help in delivering her baby, contrary to other critics’ belief that she is backward and simplistic in her conception of justice. As a final take, Hsiau emphasizes that the film responds to China’s neoliberalism and globalization, where the decreased reception of the local—or Qiu Ju—is due to the state’s modernization, which harms the interpretative moral ambiguities that make China what it is: a nation full of stories, traditions and diverse practices [21].

Overall, the three scholarly articles have one reoccurring theme underlying all of the texts and analyses, which is the fact that there is a disconnect between legality and the moral ideas of justice from the rural peasant Qiu Ju. Because there is a disconnect, Qiu Ju will never be able to obtain a satisfactory redress from the newly-formed legal system post-Tiananmen era.

Comparative Analysis

The Bureaucratic Worlds of Ikiru and The Story of Qiu Ju

Ikiru is a film directed by Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa and released in 1952, which covers the story of a bureaucratic mans quest for the meaning of his life[23]. The film shows how the main character, Kanji Watanabe (played by Takashi Shimura), can find meaning and purpose in the face of death, even in a bureaucratic system which once held him back to mindless repetition and nothingness[23]. This comparative analysis sets out to compare and contrast the aforementioned film and The Story of Qiu Ju, under the theme and discussion of the shared topic, bureaucracy. There is a reason to compare these two films, as both plots, while different, still set out to accomplish telling a story under a setting which heavily utilizes bureaucracy as it’s backdrop. As has been mentioned, The Story of Qiu Ju features the justice system in China, while Ikiru looks at a public affairs system in Japan. This comparison is important because of the differences we can find in the way the two films present their systems. We hope to illustrate that, yes, the two films both have bureaucratic thematic presence and share similarities in their representation of bureaucracy, however, while Ikiru can be seen as an outright critique, similar to what we have shown scholars like Xudong Zhang have argued in our literature review, in The Story of Qiu Ju, bureaucracy and the bureaucrats are not painted in such a negative light as it can be easy to first believe [19]. Before diving any deeper into these differences, it is important to texturally connect and assimilate these two films.

Firstly, the two films follow similarities in their plots. These plot points and stories follow the idea of repetitiveness in the face of bureaucracy. As has been covered, Zhang Yimou in his film set out to show a woman repetitively seeking an explanation from the justice system for her husband being kicked in the groin by the village chief. Of course, we see her incessantly jumping from rejection to appeal, receiving the same verdict from officers and the court. This can be connected to stories from Ikiru, such as the lower-class women at the start of the film trying to see a park built, repeatedly being sent to multiple departments to no avail. See the scene in Ikiru from 0:06:39 to 0:09:15 which shows tired women jumping from pest control to the sewage department, and like in Qiu Ju’s story, no one in this bureaucracy seems like they can help. Kanji, when he later in the film takes on the same role of trying to build this park, is very similar to Qiu Ju in that they both share large determination in the face of bureaucracy. Both Kurosawa and Yimou seem intent in the films plots on showing characters repetitive and inefficient attempts in bureaucracy.

The setting and mise-en-scene that both films frequent, is often very similar and alike as well, leading to a seeming connection between the two films. It can be argued outside of a few exceptions that Yimou in The Story of Qiu Ju uses three key settings in the film. The village, the big city, and the bureaucratic office and court spaces. Similarly, Kurosawa largely focuses a chunk of the movie in the public affairs office that Kanji works in. As seen to the right and below, this was done to place a focus on the large theme of overwhelming bureaucracy prevalent in both films, showing us the inner workings of these systems, and making the settings key locations for the characters and their stories.

Neither film is afraid to touch on bureaucracy and the corruption that can be found within it either. Akira Kurosawa focuses a large portion of the film on this idea, and it can be seen for instance in the scene taking place at 1:55:30, when Kanji has to defy the deputy mayor - who would rather talk about geisha instead of the duties of his job - to get the park made. In the film, the bureaucrats believe that “the best way to protect your place in this world is to do nothing at all” (0:06:05). Yimou has this same tendency to highlight corruption, shown in the scene where Qiu Ju “articulates to Director Yan her fear of Constable Li being a biased mediator” saying “‘You’re all officers. How would I know if you’ll all band together?” at the 1:10:34 mark [20]. In The Story of Qiu Ju, there are also scenes of potential corruption, where the verdict was suspiciously told to the Chief instead of Qiu Ju and Officer Li had to look into it again at the 1:09:26 mark. While he claims this was a careless mistake from his clerk at 1:13:48, suspicion cannot be erased just because he is nice to Qiu Ju. Something suspicious happened there, and that wasn’t the first time we saw the bureaucrats talk to Chief Wang in regards to decisions as this was also displayed in the meat market around the 32 minute mark. This similarity is important to raise because both films do fairly to include the idea and reality of corruption in bureaucracy, painting a complete and accurate picture.

Through discussing similarities, we can see how the two films discuss and focus on a similar idea, however, by looking at the differences we learn that the two are actually quite different in their portrayals. The first difference that is important to raise is the overall tone in the two films. Ikiru is a serious drama, which while occasionally including humor, is more often set out to have a serious tone. Take for example the shot from Ikiru at 1:51:46 (pictured diagonally below to the right) which uses a long take medium close up shot to show a dejected, and worn out Kanji, with his head hung who just won’t quit in getting the answer he wanted from the park chief. Kurosawa throughout the film shows Kanji as a sick man dying of cancer with a weak voice and stomach, it is hard to not feel bad for him and his journey. Compare this to Yimou’s film which often shows the main character usually as a punchline of a joke, for instance often dressed up in ridiculous outfits. While we can feel bad at points for Qiu Ju, the underlying tone is hard to forget, when the film is literally about a woman seeking an explanation for her husband getting kicked in the groin. While this comedy isn't always the case, as is shown by the serious switch during the birth scene, what the dominating difference in tone does is change the way we as viewers perceive events, and therefore perceive characters in the face of bureaucracy. We are made to laugh at Qiu Ju, and this can trivialize her quest against the bureaucracy, while in Ikiru we feel nothing but sorrow for the dying man in his quest.

Part of this also has to do with the way the directors characterize the bureaucrats. Yimou in The Story of Qiu Ju portrays each bureaucrat most often as helpful, nice, and positive individuals who will do what they can to help Qiu Ju. Examples can be how we see the director that Qiu Ju dealed with greatly apologize for his mistake at the 1:14:00 mark, and the director who calmly assisted Qiu Ju in bracing the court room, when she thought she would be suing the man who had been extremely helpful to her throughout the journey. They are displayed as so benevolent, that Qiu Ju is even scared to harm their positions and work as shown in that scene. Kurosawa’s bureaucrats on the other hand are inept, power-driven, and greedy. Take the scene mentioned in the second paragraph for example, and also the scene at the 1:38:23, which shows the deputy mayor - donned in the bureaucratic costume of a dark suit and tie - at Kanji’s wake downplaying all of the efforts that Kanji made, and claiming that the idea that he was the reason the park was made was “nonsense”, which could not be further from the truth. From this, Kurosawa had a clear vision in making his bureaucrats look malevolent, however Yimou’s characterization is not the same.

The differences do not stop there. A single song in the soundtrack plays a concrete, repetitive role in Yimou’s movie, which does not occur in Kurosawa’s. Think about how every time we see Qiu Ju depart to the city to seek some change from the bureaucracy again, we are fed into the same loop of comedy as we are played the same song over, and over again. This repetitive use of the soundtrack comedizes Qiu Ju’s journey, making us laugh at her departure and think about the unchanging result that she is going to face. No such repeating soundtrack appears in Ikiru to make us laugh at the main character and their repetitive attempts in the face of bureaucracy.

To summarize these similarities and differences, what this comparative analysis is trying to display is that by comparing Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru to Zhang Yimou’s film The Story of Qiu Ju we can see that the latter is not as extreme of a critique of bureaucracy. While yes, both films share the theme of bureaucracy and the similarities of displaying inefficiencies, and corruption surrounding bureaucracy, with a frequent bureaucratic setting, Ikiru’s much harsher tone, negative characterization, and lack of recurring comedic soundtrack illustrate a more pointed example of a critique on the negatives of bureaucracy. Similarly to the Zhang piece we covered in the scholarly literature, this makes the theme of bureaucracy in The Story of Qiu Ju seem more like a flawed, yet neutral participant of the era in the comedies of Qiu Ju’s life, than an active target of Zhang Yimou’s film[19]. Qiu Ju does struggle with bureaucracy, but unlike Ikiru, it’s hard to tell if Zhang Yimou wanted to display this struggle, as the fault of the said bureaucracy.

Alternative Interpretation

Against Moral-Legal Codes: Queer Femininity

Unfolding through a rural village in northwest 1990s China and amidst its project of modernity, scholars largely hail The Story of Qiu Ju as depicting the clashing of bureaucratic legal codes and the private sense of moral legitimacy through a woman’s stern quest to avenge her husband’s assault. This is where neither Qiu Ju’s headstrong want of justice nor the Chinese legal system and its universalism prevails one another. Hsiau, Sze-Lorain and Zhang capture this sentiment in their articles, arguing that the film seems to convey the aperture between private moral justice and public legality in 1990s China [19][20][21]. Though, in a world fraught with husbands, male chiefs and male officials such as The Story of Qiu Ju’s, while scholars have touched upon Qiu Ju’s female identity in their justice-bound analysis, it’s a surface reflection on her femininity. This thus abstracts the story from its gendered realm, and into an even more universalist fiasco on whether moral or legal codes matter more.

Agreeably, while there is a conflict between bureaucracy and individual sense of legitimacy, the film’s plot doesn’t unfold through such binary. Rather than questioning the abstract nature of justice alone, I argue, Qiu Ju is on the quest to defy the world of Freudian phallic, amidst the loss of it—her husband’s kicked groin. As such, while nuancedly treading the topic of the legal system and individualist justice at the crossroad of Chinese modernism, scholars—at the same time—forgo what enacts the plot. It’s the law of sexuality, rooted in queerness, as seen through Qiu Ju’s critical belief in fertility and egotistic sense of justice. I thus argue that while there is an inherent conflict between self-justice and the larger-than-life legal system, there is also—more importantly—Qiu Ju’s quest for redefinition of sex through her husband’s ‘lack’ of it, prevailing the abstract nature of law, and becoming the law itself: the law of sex and of queering gender. Thus, by reconceptualizing the film’s through the gendered realm during 1990s China, I suggest that the film also subverts this metanarrative of Chinese modernism.

Scene Analysis

Throughout the film, moral-legal codes and self-legitimacy undulate and come into being between conflicts over fertility symbols and gender dichotomy. In specifics, what begins Qiu Ju’s quest for justice is also what concludes it: the presence of the phallic, or the kicked groin of Qiu Ju’s husband and the birth of her son, mediated only by her queer and feminine presence.

Scene 1 & Clip 1 (24:15-26:20)

In a rural village’s bazaar, Qiu Ju carries on her family business of selling chilies to get to justice in the city. Yet what translates into justice here may as well be a phallic symbol: chilies, where Qiu Ju and her husband’s sister, Meizi, literally bargain for higher prices to buy their fare to town, or to Qiu Ju’s quixotic quest of justice. This then is the negotiation between the loss of sexual subject and individual sense of legitimacy. The gendered life of Qiu Ju begins tumbling down the moment her husband’s genitalia is damaged. Her quest of justice for her husband then is also rooted from her feminine ego, displaced and in need of redefinition when its opposite is temporarily gone. The chilies—presumably a phallic symbol—being converted into material values here speaks to how Qiu Ju is dismantling her gendered life for self-legitimacy.

Later on, when Qiu Ju and Meizi get to the district, there is a deep focus and close-up shot of walls, plastered with images of gender dichotomy and fertility: from the God of Wealth Caishen with an abundance of rosy-cheeked children to Westerners’ intense sexuality and China’s own array of young and beautiful males and females. With a disarray of images collaging on top of one another, Qiu Ju sets foot in a world where gender boundaries are blurred and non-essential. This liminal world of sex contrasts with prior scene’s gendered realm of Qiu Ju selling chilies. It also parallels the character’s almost queer attempts to—despite her husband’s caution and the village’s gossip—repeatedly seek self-justice. The self here then is not an abstraction of strict moral codes, but it’s also imbued with queerness and agency.

Scene 2 & Clip 2 (1:35:21-1:37:35)

By the film’s end, Qiu Ju seemingly attains her self-justice when the village’s chief helps her deliver her baby. Once more, the character’s world re-orders itself with an appearance of the phallic, the baby boy. Yet amidst the family’s exuberant celebration of the birth of more maleness, is a particular close-up shot of Qiu Ju carrying the baby’s through a hole of a large, circular bread, which presumably resembles a vaginal and fertility symbol. Through jovial diegetic instrumentals, the villagers with Qiu Ju then resolve to eating the bread when the boy has passed through the hole. It’s this performance of gender role that queers the film’s depiction of justice, where Qiu Ju is not so much only a child bearer but is, also, the phallic order which thrusts the baby through.

Near the scene’s end, through a medium-long shot and low-key lighting, when Officer Li announces that the village chief has been detained for assault, Qiu Ju expressively concerns over the man’s situation through her visible anxiety and furrowed brows. Again, the birth of a new phallic symbol is the loss of the old one, or the village chief, yet Qiu Ju is the mediator of all of this. Albeit seemingly confounded by her own self-justice, this character is naively performative. Throughout the film, she single-handedly dictates what femininity, legality should be and bears the phallic symbol in her family without much retribution.

Very much so, fertility symbols and gender dichotomy precede and undergird what seems to be a portrayal of moral-legal codes in The Story of Qiu Ju. Other scholars’ binary view that configures the world of The Story of Qiu Ju breaks open with a third component: gender subversion and queer femininity. Qiu Ju then is fallible, in her own failing justice and regret. Yet, one can also interpret that, intertwined in the arbitrary justice, the character subverts the trope of the phallic, and takes on the masculine ego. She thus engenders the modernist project of 1990s China through her individuality and obstinacy, almost bearing both the patriarch and matriarch title in her family through her quest towards self-justice.

Subverting the Phallic and China's Modernist Project

Neither achieving an apologetic village chief nor what she deems as rightful compensation through China’s mediative and legal courts, Qiu Ju resorts through queering the phallic order of the world, by both deconstructing and constructing it anew, going to court again and again and regretting it later on. The character is not so much reigned by this phallic symbol, but rather, she obsesses over its dislocation, its lack. For the character, to gain justice or not isn’t what she desires. But rather, to agentically and womanly enact herself, to headstrongly resist the pre-dictated meaning system around her is what Qiu Ju wants, as evinced by the character’s uncanny sense of justice, queer feminine ego and constant negotiation between phallic symbols to validate her own legitimacy (e.g. conflict over the chilies business, the market’s various images of sexuality). Then, justice—merely a backdrop—is just a performative act by Qiu Ju to subvert the phallic.

Qiu Ju’s gender subversion also dissolves the legal-moral codes that other scholars often portray as inherent to the film's themes, through her own queer femininity that dictates justice, itself. By othering the seeming inherence and abstraction of these codes, Qiu Ju denaturalizes this grand narrative of Chinese modernity, as it is built on these codes. Qiu Ju then is a critique of China's modernist project. The character, too, sheds light on the fragmented female subject at the heart of 1990s China, amidst forces of private moral codes and the larger-than-life, public legal system.

Not necessarily defined by her own private self-justice or the public bureaucracy, Qiu Ju, by the end, anxiously gazes over the snow-capped landscape around her, towards the village chief’s detainment. Many read this final shot as Qiu Ju expressing her utmost anguish [24]. Yet, this zooming in on the character’s face does nothing but to enlarge and give shape to her queer presence: the sole enactor of the film’s subversive femininity and its unforgiving closure.

Conclusion

Zhang Yimou's The Story of Qiu Ju entails Qiu Ju's navigation of the Chinese legal system post-Tiananmen Protests, which the character finds unanswering towards her sense of self-justice. Critics generally hail the film's social-realist portrayal of rural China, especially its minute inclusion of then people's daily life. Albeit repetitive, critics, globally, commend upon Zhang's documentarian style, natural lighting and his intentional use of non-actor crowds to heighten the objectivity and realism of the themes portrayed [16]. As critically acclaimed as it is, scholars find themselves divisive upon interpreting the film, with one side condemning Qiu Ju as backward and deprived of legal dignity by the Chinese legal system [19][20][21]. The other—taking a more nuanced stance—simply implies Chinese particularistic moral-cultural codes as at odds with newly ushered in Western liberalism and its universal court system [19][20][21]. In a sense, Qiu Ju's Chinese private self-justice is mutually exclusive with bureaucratic legal codes. Nonetheless, like many other lasting films, Zhang has delivered The Story of Qiu Ju with a heightened sense of directorial finesse, presenting us with a challenging work around the complex gap of legality and self-justice. As the zeitgeist shifts, while many will change their perceptions on the film's socio-political sphere, aesthetics and themes, yet, no-one can deny its true-to-heart depiction of rural Chinese's spirited perseverance.

Our group generally has a pleasant perception of the film, thinking it was a socially conscious comedy-drama incentivizing people to not only laugh at Qiu Ju's headstrong-ness, but also to reflect on public legality and private self-legitimacy in then modernizing 1990s China. Regardless of age, we recommend the film to anyone. We trust in the actors' faultless acting, the film's timeless portrayal of rural living at the edge of change and the ending's twist of fate to viscerally challenge viewers' critical thinking while at the same time giving each a good, hearty laugh. One of the first works in the master's—Zhang Yimou, himself—repertoire, we see The Story of Qiu Ju as a salutary gesture towards a fading socialist China, in all of its light-hearted glories and ironies.

To recap, first, our stories behind the film have explored The Story of Qiu Ju's uncanny creation, and we have also investigated the film's global and local receptions, finding out that the film received generally positive reviews. Next, in our scholarly literature review, we were able to take deep dives onto analyses of the film, regarding its cinematography and the overall thematic messaging. One of the major aspects we learned was the presence of a disconnect between Qiu Ju's idea of justice and the legal system's idea of justice. Then, by comparing Ikiru and The Story of Qiu Ju, our comparative analysis makes an argument on the two's contextual similarities, especially in their presentation of bureaucracy. However, we also illustrated—through the differences— a lack of an apparent and strong critique of bureaucracy in The Story of Qiu Ju. To conclude, ultimately, we realize the alternative interpretation by denoting Qiu Ju’s queer performance as dictating the phallic, thus dictating the meaning-making system of justice in the film and 1990s China’s modernist project.

References

</references>

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "The Story of Qiu Ju". IMDb. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "《秋菊打官司》:人设改变,故事背景改变,电影的格局更深刻了". Sohu. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "张艺谋作品:《秋菊打官司》". ifeng. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "秋菊打官司 获奖情况". Douban. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "张艺谋在陇县拍摄电影《秋菊打官司》的幕后故事". Sohu. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 "文艺纵横|《秋菊传奇》凭什么让影视大咖们时隔30年一再挖掘". Baidu. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 "张艺谋:我应该是中国最早的偷拍的大师了,比狗仔队还要早". Bilibili. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 "从"秋菊"到贾桂花——首例因拍摄电影引发的公民肖像权诉讼". Sina Corporation. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 "叙事、文化与正当性:张旭东论《秋菊打官司》". Guancha. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Red Tape". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Ebert, Robert. "The Story of Qiu Ju". RobertEbert.com. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Spence, Jonathan. "Unjust Desserts". The New York Review. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Kempley, Rita. "The Story of Qiu Ju". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "秋菊打官司 (1992)". Douban. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "秋菊打官司". Maoyan. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "The Story of Qiu Ju". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "The Story of Qiu Ju". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "秋菊打官司". Maoyan. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 Zhang, Xudong (2008). Postsocialism and Cultural Politics: China in the Last Decade of the Twentieth Century. Duke University Press. pp. 289–310. ISBN 978-0-8223-8893-7. line feed character in

|title=at position 37 (help) - ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 20.11 Sze-Lorrain, Fiona (Fall 2006). "Qiu Ju Goes to Court: Relating Cinematic Art to Juridical Reality". Asian Cinema. 17: 173–181 – via Intellect Discover.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 21.9 Hsiau, A-chin (Spring 1998). "The Moral Dilemma of China's Modernization: Rethinking Zhang Yimou's "Qiu ju da guansi"". Modern Chinese Literature. 10: 191–206 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "《幸福到万家》与《秋菊打官司》相比,故事逻辑牵强". 163.com. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Ikiru". IMDb. IMDb. Retrieved 17 June 2023. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Larson, Wendy (2017). Zhang Yimou: Globalization and the Subject of Culture. United States: Cambria. ISBN 9781604979756.