Course:ASIA325/2023/Immigration from an Asian Perspective: The Story of Woo Viet (1981)

Group Members' Contributions

| Contributor(s) | |

|---|---|

| Introduction | TW |

| Stories Behind the Film | CC |

| Histories of the Film's Reception | GM |

| Scholarly Literature Review | CC, GM, TW |

| Comparative Analysis | CC, TW |

| Alternative Interpretation | GM |

| Conclusion | TW |

Introduction

The Story of Woo Viet is a 1981 film directed by Ann Hui. The film premiered on April 24th, 1981 and is the third film in Ann Hui’s “Vietnam Trilogy”. It stars Chow Yun-fat (Woo Viet), Cherie Cheung (Shum Ching), Cora Miao (Lap Quan), and Lo Lieh (Ah Sarm).

Woo Viet is a young Chinese-Vietnamese man recently discharged from the South Vietnamese Army who leaves Vietnam for a fresh start in the United States. He first makes his way to Hong Kong where he meets Shum Ching (Cherie Chung), another refugee from Vietnam, who he falls in love with. Together, they disembark Hong Kong for America, however, in a stop-over in the Philippines, Shum Ching is kidnapped and sold into prostitution. Woo Viet decides to stay in the Philippines and works as a hired killer for the gang that kidnapped Shum Ching to pay off her ransom.

The following sections look at the historical context of the film’s production and reception, how the film has been studied in scholarly works, its similarities and differences to another film with a similar theme, and an alternative interpretation of two scenes within the film. Overarching this analysis of the film is the theme of immigration, in particular, the struggles of Asian immigrants moving to foreign lands.

Stories Behind the Film

From an interview conducted by the 2021 New York Asian Film Festival (NYAFF), Ann Hui shared stories detailing her experience working on the film The Story of Woo Viet. Prior to the movie The Story of Woo Viet, Chow Yun Fat was not as famous as today. Hui expresses her gratitude towards Chow because he tried really hard to push the production of the movie to Television Broadcasting (TVB) which is a major television broadcasting company in Hong Kong. Even before Chow’s rise to fame, Hui stated that people knew he was a capable and talented actor because of his body language, mastery of character enactment and expressiveness. Not only was he skilled but he was hard working and kind to the production crew.

Hui tells the story where Chow would routinely go to the food market and buy ingredients to cook meals for everyone on the days when they were not filming. Since all the crew and staff lived in two short term rented flats, he invited everyone to come over on the weekends to enjoy snacks after shooting. He was very cooperative and did not challenge the script or directing of the movie. However, later in Chow’s career, he dabbles with the creative direction of future films. Hui recalls the era of independent filmmakers in the 1980s Hong Kong cinema scene. Many directors did not last in the industry and ended up making one or two films before leaving and the investors of these independent films were somewhat random. For example, one investor of The Story of Woo Viet was a dealer of curtains in Pearl City and they went on to invest in other films created by directors like Stanley Kwan. Due to the miscellaneous investor funding, they didn’t have an official office. Hui recollects memories of the film crew moving around with all the paperwork and scripts in their big bags as they travel around for office spaces.

When the discussions of the film were in the works, Hui proposed the idea of going to America to film the Chinatown scenes which are a crucial part of the plot. Due to the lack of financial support from Radio Television Hong Kong, the proposal of going to America was shot down. Back then, it was very uncommon for films to be shot overseas therefore the movie was temporarily dropped as a whole. As the movie blueprints shifted from going to the US for Chinatown to going to the Philippines for Chinatown, the green light was given for the movie production to begin.

Eventually, Hui contracted fellow friend and screenwriter, Alfred Cheung to write the script for the movie, which was immediately accepted by Cora Miao who plays the role as Li Lap-Quan. Hui did not believe that the script aligned with her vision for the film and ultimately scrambled to find another screenwriter, Kong Kin Yau to change the script entirely. She did not look forward to having a conversation with her friend Cheung but he was supportive of her decision. Hui had to adjust to the movie being filmed mostly in a Chinatown in the Philippines based on the new script. To her surprise, filming more scenes in a Filipino Chinatown allowed her to dramatize the film the way she had envisioned because not very many people understood the culture nor the place compared to the Hong Kong familiarity with America.

Histories of the Film’s Reception

The 1981 film, The Story of Woo Viet, also known as God of Killers on filmaffinity, is regarded by the general public as one of the more mediocre films by Ann Hui. The box office for The Story of Woo Viet hit 3.8 million HKD[1]. For comparison, the title of best-selling film in 1981 is held by Michael Hui’s comedy film Security Unlimited, with a box office near 18 million HKD[2]. Rating wise, on Chinese film platform douban (豆瓣電影), The Story of Woo Viet was given an average rating of 7.1 out of 10[3]. However, the English-speaking audiences do not perceive the film as well as the Chinese audiences, the film scored 6.5 out of 10 on IMDb[4] and 3.4 out of 5 on Letterboxd[5], but it is worth to notice that the sheer number of reviews on these Western-culture film sites on Ann Hui’s film is significantly less than douban. Despite mediocre reviews by the public, the film was well perceived by the authorities, such as Hong Kong Film Awards. The Story of Woo Viet was one of the Top 10 Chinese Films on the 1st Hong Kong Film Awards[6], and the film also helped screenwriter Alfred Cheung Kin-Ting won the Best Screenplay awards[7]. The awards received by the film indicates it was liked by professional local film critics.

By comparing critics of local/Chinese-speaking and international audiences, we can see local viewers tend to like the film more than international audiences. One of possible reason causing the difference between Chinese and Western reviews on the film could be due to the relatability to the film’s theme, the struggles of Asian immigrants moving to foreign lands.The Story of Woo Viet uses Vietnamese boat people as the vehicle to convey struggles faced by Asian immigrants. The Vietnam War lasted almost 20 years from mid-1950s to mid-1970s, which the communist regime from the North eventually won. A lot of Vietnamese people that supported the regime in the South fled their home country in fear of the Communist regime. Hong Kong declared itself as “port of first asylum” for Vietnamese boat people in 1979[8], while The Story of Woo Viet was released in 1981, at the peak of the boat people issue. The social realities of the film certainly add to the film’s relatability to local audiences, but maybe not as well for international audiences as they are less familiar with the historical context of the film. By reading reviews on the film by netizens, in general positive comments praised the film in doing a good job of portraying situations refugees used to face, and the vision held by refugees that could not be realized. On the other hand, negative comments focus on the film’s plot being hard to follow and hard to understand, which we believe is due to the film requires its audiences to be familiar with the historical background of the film.

Scholarly Literature Review

Looking Back at Ann Hui's Cinema of the Political - Ka-Fai Yau[9]

In Ka-Fai Yau’s article, Looking Back at Ann Hui's Cinema of the Political, Yau analyzes the “political” in four of Ann Hui’s films, one of which being The Story of Woo Viet. With regards to The Story of Woo Viet, he highlights four aspects of the film that make it part of the “cinema of politics”, that is, the cinema about politics.

Firstly, Yau states that the Vietnamese refugee crisis depicted in the film is a metaphor for Hong Kong’s future after the 1997 handover to China. Specifically, he notes how the lives of the Vietnamese boat people in the film possibly foreshadow the fate of Hong Kong citizens after the communist Chinese government takeover. Yau also highlights the tension between Vietnamese refugees and Hong Kong citizens due to the increased economic burden on Hong Kong for settling these refugees. As a result, he says the film acts as a mirror to show the tense encounter between these two groups.

Yau believes that the film also demonstrates how Chinese people suffer from a destiny of exile. He says that this is shown through the character of Woo Viet. Woo Viet is Chinese-Vietnamese, meaning his ancestors had previously immigrated from China to Vietnam, likely to escape the unstable situation in China. In a similar vein, the film shows Woo Viet leaving Vietnam for the United States following the end of the Vietnam War. As such, Yau states that Woo Viet, like his forefathers, is condemned to a life of exile, making his situation representative of the greater Chinese diaspora.

While Yau describes Woo Viet as a representative for the exiled Chinese, he asserts that Lap Quan represents the “missing and impotent Hong Kong people”. This is because Lap Quan is merely an observer in the film. For example, she only learns of Woo Viet’s story through the letters he writes to her. In addition, despite the letters being addressed to her, she remains a voiceless figure throughout the film; the audience does not learn about her thoughts of the letters through any voiceovers or meaningful dialogue. Hence, Yau states that she symbolizes the invisible Hong Kong observer that can only sit back and watch Hong Kong change, for the better or for the worse, as time passes. Yau also says that Lap Quan’s silence in these situations allow her to be a blank canvas for a Hong Kong perspective to be projected upon. The spectator is invited to use her silence as an opportunity to contemplate the status of Hong Kong. According to Yau, the last scene in the movie where Woo Viet is reading a letter he has written to Lap Quan serves this purpose. Lap Quan’s absence in this scene leaves the Hong Kong spectator wondering if Woo Viet’s destiny is reflective of that of the Hong Kong people in the future.

Lastly, Yau says that an analogy can be drawn between the “overseas Chinese” and “Hong Kong people” as they both suffer from a floating identity problem. He points out the characters Woo Viet and Ah Sarm as examples of “overseas Chinese” that struggle with their identity. In Woo Viet’s case, he quickly moves from Vietnam to Hong Kong then the Philippines. This constant state of exile prevents him from establishing any notion of self-identity. Similarly, Ah Sarm, despite having settled in the Philippines, still lives a “soulless” life as his only desire is to get drunk. Therefore, Yau indicates that the floating identity of both these “overseas Chinese” characters parallels the identity crisis of the “Hong Kong people” leading up to the 1997 handover.

At Full Speed: Hong Kong Cinema in a Borderless World- Elain Yee Lin Ho[10]

In this chapter of the book, At Full Speed: Hong Kong Cinema in a Borderless World, Elaine Yee Lin Ho described the way Ann Hui’s movies were influenced by the intersectionality of her identity. In the historical context that is the 1980s Hong Kong which is looming with cultural uncertainty and rapid urbanization, comes the New Wave of Hong Kong Cinema. Ho used the colonial history and modernistic gender associations to spell out the times that Ann Hui was in. The constant back and forth between the Westernized ideologies and the Chinese impact is attributed to the genre of political and personal drama films Hui created.

Hui’s impressive educational background from the University of Hong Kong and the London Film School honed her technical skills so she could create films that help illustrate the complex cultural identity of Hong Kong in the 1980s. Starting out in television, she eventually moved to cinema and pioneered a new perspective on women characters in films. In her earlier public statements, Hui rejected the statement that she is political or feminist but in more recent films, Hui reinvented the women who are characterized in her films. From succumbing to the patriarchal society in older films, newer films assigned a label of modernity embracing a movement that empowered women.

"Crossing Borders: Time, Memory and the Construction of Identity in Song of the Exile"- Patricia Brett Erens[11]

In the article "Crossing Borders: Time, Memory and the Construction of Identity in Song of the Exile[11]," Patricia Brett Erens divides Ann Hui’s cinematic works into three categories: genre films, typical of the Hong Kong film industry; political dramas; and personal works. In particular, the article delves into the film Song of the Exile which is a combination of a political drama and a personal work as per Erens’ argument. Erens argued the film served as a political allegory for the 1997 hand-over and examined the national, cultural and personal characteristics of identity. Erens cited Stuart Hall’s two-part definition of cultural identity which are: the collective, shared cultural aspects of an identity and the personalized self which specifies individualized differences from person to person. Applying this example further, the Hong Kong identity formed was not a simple binary but Hui continuously challenged the boundaries between the eternally fixed colonial past and the future movement of Chinese cultural belonging.

In this exile cinematic piece, Erens pointed to the vocal defence the character Hueyin had for her ethnic differences but maintained her silence when it came to her internal conflict with alienation and discrimination. Hueyin lacked a cultural belonging in the new place and relied external meanings Erens elaborated on the theme of revisiting the past which involved the reliving the memories in Song of Exile. Both characters Hueyin and Aiko in the movie feel disconnected from a cultural root of theirs and suffer from a traumatic attachment to their past or homeland. Erens stated this is a similar trauma for Hong Kongers as they grapple with the dubiety of their heritage. Furthermore, exile writing typically follows a trajectory that aims to build a safe refuge but these do not exist in Chinese exile writing according to Erens. Referencing an interview with Ann Hui, Hui believed “nationalism is a product of education” and “Hong Kong Chinese are merely confused when they look to China for their sense of belonging.” Erens ends with another reference to Stuart Hall’s essay “Cultural Identity and Diaspora” which establishes identity through representation instead of through constructions of traits and experiences.

"The New Wave" from Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions- Stephen Teo[12]

Chapter “The New Wave” from Teo’s book Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions explored the situation of Hong Kong’s cinema industry in the 1970s before the New Wave, the emergence of the New Wave, as well as significant directors of the New Wave. This literature review will only be focusing on the parts of the chapter that relates to the emergence of the New Wave and the part on Ann Hui.

First, Teo argued the emergence of the New Wave is the inevitable product of its time. Teo suggested 1970s was a remarkable century in Hong Kong history as Hong Kong was experiencing transition in the socio-economic aspect. The drastic societal change brought along new social problems in the 1970s such as labor exploitation as well as police corruption. These problems on society required representation in the cinema industry. The New Wave emerged in the late 1970s, which many of the new directors tapped into the crime thriller genre. The New Wave have brought back a new form of social realism that crime and police corruption were strong presence.

Second, Teo stated the New Wave was driven by a group of up-and-coming directors who had higher standards on the artistic aspect of the film. Most of the young directors in the New Wave, including Ann Hui herself, had studied in foreign film schools, which brought improvements to the professional standard, techniques and special effects used in the film industry. Teo argued the New Wave directors burst into the scene because they successfully satisfied the appetite of young film audiences.

Teo also pointed out Hui’s film such as The Story of Woo Viet are unconsciously products of social conscience. The topic of Vietnam boat people was not entirely new to Hui, The Story of Woo Viet is often considered as the unofficial Vietnam trilogy by Hui, alongside The Boy from Vietnam and Boat People. The trilogy explored how Vietnamese refugees affected Hong Kong’s politics and society. Teo argued the displaced Vietnamese refugees in Hui’s trilogy acted as the vehicle for Hui to explore the sensitive relationship and the future between China and Hong Kong.

Finally, Teo argued Woo Viet in the film was experiencing an existential crisis. In the film, after getting stuck in the Philippines, Woo Viet was forced to hide in the underground world of Manila by working for a gang boss in Chinatown. On top of that, there was another conflict between Woo’s goals, on one hand, he works for the gang, while on the other hand, his friend Shum is kept by the gang under sexual bondage. Teo suggested Woo’s situation in Manila has an existentialist overtone. I interpret Teo’s point as Hui is exploring not only Woo’s existential crisis, but also Hong Kong citizens’ identity crisis regarding their future with China.

Comparative Analysis

Minari[13] is a 2020 film directed by Lee Issac Chung. The film follows the Yi family, a Korean immigrant family hoping to make it in rural Arkansas after moving from California. It stars Steven Yeun (Jacob Yi, the father), Han Ye-ri (Monica Yi, the mother), Alan Kim (David Yi, the son), Noel Kate Cho (Anne Yi, the daughter), and Youn Yuh-jung (Soon-ja, Monica's mother). With its focus on Asian immigration, the film offers a good comparison to The Story of Woo Viet.

Similarities

The theme of immigration for a new start in America was a key similarity between the films The Story of Woo Viet and Minari. The Story of Woo Viet by Ann Hui was placed in the 1970s where there was an influx of Vietnamese refugees and specifically focuses on the journey of a war veteran named Woo Viet. He had plans to go to America for a new start but ended up staying in the Philippines out of a heroic act to save a woman he fell in love with. Minari by Lee Isaac Chung was set in 1983 in Arkansas in the United States, following the story of a Korean immigrant family that recently moved there from California. The family in Minari consisted of a father named Jacob, a mother named Monica, a daughter named Anne, a son named David and a grandmother named Soon-ja. The main characters of both films emphasized a new beginning by immigrating to America. Despite different motivations, they shared the understanding that once they got to America, they would get a fresh start. Building on this similarity of Asian-American immigration, the characters in both films faced a form of unforeseen change in their circumstances. In Minari, Monica did not know much about the farm dream that Jacob had nor had she expected to move into a mobile home far from the city. In The Story of Woo Viet, Woo Viet and Shum Ching ended up in a Chinatown in the Philippines when they were set to go to the US.

Even though their realities did not meet their expectations, they persevered through the new problems that arose as a result of the new location.

Given their respective historical contexts, they portrayed realistic storylines, imagery and dialogue. Drawing on this realism, both movies depicted the desire to find an ethnic community to fit into. In Minari, Monica met another Korean woman who worked at the chicken hatchery with them. She found comfort in meeting someone who shared the same ethnic identity and likely the same ethnic struggles given they were in Arkansas in the 80s. Eventually, Monica visited a nearby church with intentions of meeting people that shared the same religious values as her. Just like Monica, Woo Viet and Shum Ching ended up in Chinatown where they found other Chinese people to help them. Woo Viet worked as a hitman for a Chinese club owner and gangster but he needed the support from him to survive in the foreign land of the Philippines. The theme of finding ethnic community is prevalent in both films. It was a consolation for the characters to get a sense of belonging.

Furthermore, the two movies show women who followed their male love prospects to an unfamiliar place. In Minari, Monica did not know what the new home looked like nor did she know of Jacob’s aspirations around a farm. In The Story of Woo Viet, Shum Ching barely knew Woo Viet before she trusted him and decided to follow him. Throughout the movies, the female main characters compromised their living standards and personal goals to support the inconsiderate and reckless decisions made by the male main characters. For example, Monica was opposed to the farm because the home was far from the hospital which posed a risk for David and his heart condition as well as the questionably hefty financial investment into the farm. Monica made the difficult decision to leave Jacob because she could no longer support his dreams at the cost of the family. Admittingly, Monica ended up staying with him but she did come to the conclusion of leaving him at one point.

In The Story of Woo Viet, Shum Ching told Woo Viet that she wanted to follow him when they arrived in the US. At this point, Shum Ching’s immigration to the US was subsidized by another man.

The Story of Woo Viet ends in a violent and bloody fight between the gangsters and Filipino police and ultimately Shum Ching dies in an altercation. Although Shum Ching was never going to arrive in the US as she was kidnapped for sex work, her death was a direct consequence of Woo Viet’s rash actions.

Ann Hui and Lee Isaac Chung characterized the women in both films as loyal people who ran out of faith and time. It draws on the ideals of a trusting woman who believed in a man that prioritized themselves over everyone else. The rationale behind the male characters’ actions could have been justified because they were done out of care for the other characters but both male characters indulged in unnecessarily selfish and perilous acts. For example, Woo Viet’s engagement in the gun fight led to the death of Shum Ching and Jacob’s commitment to the farm led to the family not having enough water and Monica’s verdict on leaving.

Differences

One difference between the films is the emphasis they put on family. In The Story of Woo Viet, there is absence of family. The film is a tale of an individual’s journey (Woo Viet) from Vietnam to the United States. As a result, Woo Viet must endure the hardships he experiences purely on his own. The closest thing we see to family in the film is the relationship between Woo Viet and the young boy he meets on the boat he takes from Vietnam to Hong Kong. Even then, Woo Viet only takes care of the boy because his father was killed by the guards on the boat. In addition, Woo Viet ends up abandoning the child in Hong Kong after he is forced into hiding for killing a government special agent. While family does not play a major role in The Story of Woo Viet, family is the central focus in Minari. The film is about a Korean-American family that moves from California to rural Arkansas and their shared struggle to make a living while assimilating to a new society. This is not an easy process for the family, and nearly results in the family breaking apart; the hard life in Arkansas makes Monica want to move back to California for a more stable life, however, Jacob is determined to see his new farm in Arkansas flourish, thinking that its success will provide them a better life in the future. But, in the process of chasing his dreams for success, Jacob causes his family to suffer as he uses all of their savings for his farm. Only when Jacob loses all of his crops to a fire does he realize he has lost track of what is important—family.

The films also differ in their settings. In The Story of Woo Viet, Woo Viet jumps around from place to place, moving from Vietnam to Hong Kong then the Philippines. As such, he lives in an unending state of exile in which there is no opportunity for him to establish an identity for himself. In contrast, the Yi family in Minari stays in Arkansas after moving from California. Although they initially struggle to find their place, they eventually start to assimilate to the new society and craft an identity of their own. For instance, Anne and David become friends with local kids; Monica learns to accept their situation despite originally having reservations about moving from California, bonds with Paul over religion, and builds camaraderie with a fellow Korean woman at the chick hatchery she works at; Jacob learns to trust his neighbors, realizing that the locals know better than him in some aspects, like finding a place to dig a well; and Soon-ja starts to indulge in western media and food. Unlike Woo Viet, the Yi family is able to develop their identity in this new location.

Another difference between the films is their depictions of people in foreign lands. The Story of Woo Viet portrays them as evil and manipulative. For example, in Hong Kong, Woo Viet is almost assassinated by a government special agent. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, he is taken advantage of by the gang that kidnapped Shum Ching to do their dirty work. On the other hand, the Arkansas locals are generally welcoming to the Yi family in Minari. After just settling into their new home, Paul approaches Jacob to help with the new farm he wants to start. As a religious man, Paul prays for the family and even offers to perform an exorcism on their property to get rid of the “evil spirit” bringing misfortune to the family. The family is also welcomed at the church they attend in the nearby town despite being the only Korean family, let alone people of color, in the congregation. For instance, after attending their first service, some women offer to help Monica learn English after she tells them her English is not very good, and David quickly becomes friends with another young boy he meets.

Alternative Interpretation

The two scenes our group is interested in investigating are the scene of the conversation happened not long after Woo has just first met Shum when they were waiting for the elevator, and the scene that shows Woo’s work in the underground casino in the Chinatown of Manila.

Scene 1: (18:49-19:29)

This scene depicts the first time Woo and Shum get to know each other as they were getting off class. This is a long take that gives us uninterrupted access to their conversation. Their conversation started by Shum offering Woo a cigarette, which Woo has rejected the offer by stating his does not smoke. Shum was surprised by Woo’s response as we would expect many soldiers on the frontline may rely on smoking and drinking to de-stress themselves. The props and clothing of the characters are colorful in the scene, suggesting this is a joyful and hopeful moment for the two characters.

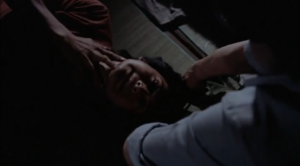

Scene 2: (1:05:25-1:05:50)

This shot is a depiction of Woo’s day at work under Mr. Chung. The shot starts as a close-up on Woo, then gradually transitioned into a shot with a deep focus onto the gamblers in the background. This shot establishes the place Woo is situated in and the action he is taking. At the start of the shot, Woo is smoking a cigarette, and the shot ends with Woo drinking the rice wine that AH Sarm tossed to him. This scene suggests the tremendous stress he is experiencing since getting to Manila is hard to overcome and he must rely on both smoking and drinking (as there is a scene before this one that he was smoking but refused to drink). The color tone in this scene is relatively pale compared to the first scene, suggesting Woo is realizing the hopelessness of the situation he is in.

If we exclude the possibility of Woo lying to Shum when he says he does not smoke, Woo managed to stay away from cigarettes and alcohol after all those years fighting in the Vietnam War but started to smoke and drink after leaving Hong Kong. Woo smoking in the second scene contradicted what he said in the first scene, showcasing his experience in the Philippines is more stressful and traumatizing than being in a war, as the chance of him to start a new life in the US seems less and less possible.

Generalizing Woo's experience into the grand theme of our project, to many Asian refugees/ immigrants, the experience in their home countries is actually less traumatizing than what they experience after arriving in the new country. To many Asian immigrants, the process of realizing their dreams are beyond reach is more painful and traumatizing then the trauma they experienced before leaving their home country because they had a dream to hold onto.

Conclusion

The Story of Woo Viet was well-received by Chinese audiences and critics alike, however, international audiences did not perceive the film as well. In our opinion, the film was enjoyable. Having watched Boat People before this film, it was interesting to see this movie expand on the story of the Vietnamese boat people by depicting the life of a boat person (Woo Viet) after leaving Vietnam. The film is also effective in revealing the severity of the refugee crisis after the Vietnam War as we witness the hardships Woo Viet has to endure while trying to immigrate to America. We found the film lacking in one aspect, however, which is that it is hard to follow at times. We felt that some important points in the plot are brushed over too quickly or presented in an unclear way. For example, when Woo Viet and Shum Ching leave Hong Kong for America, it is unclear where they stop-over for a connecting flight to the United States. We only find out later, when Shum Ching is kidnapped and Woo Viet goes looking after her, that they are in the Philippines.

As we enjoyed the film, we recommend that others also watch The Story of Woo Viet. Current and former refugees would likely enjoy this film as they can relate to Woo Viet’s situation. In particular, his continuous state of exile, struggles to assimilate to a new culture and society while in the Philippines, and tumultuous journey to reach his destination are reflective of the hardships that many refugees experience. As a result, this film is likely to hit home with those who share these same experiences. The film would also be appreciated by people who enjoyed watching the other films in Ann Hui’s “Vietnam Trilogy”. As mentioned above, The Story of Woo Viet builds off of the preceding films in the trilogy, specifically Boat People, as it offers a look into the life of a Vietnamese boat person after leaving Vietnam. As such, those who found the other films in the trilogy entertaining are likely to enjoy The Story of Woo Viet as well.

References

- ↑ "胡越的故事". Wikipedia. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ↑ "摩登保鑣 (1981)Security Unlimited". HKMDB Hong Kong Movie Database. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ↑ "胡越的故事". 豆瓣. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ↑ "The Story of Woo Viet". IMDb. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ "The Story of Woo Viet (1981)". Letterboxd. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ "第1屆香港電影金像獎". Wikipedia. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ↑ "胡越的故事(1981) The Story of Woo Viet". HKMDB Hong Kong Movie Database. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ↑ Bradley, Faye (April 27, 2022). "When the Boat People Came to Hong Kong". Sixth Tone. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ↑ Yau, Ka-Fai (Fall 2007). "Looking Back at Ann Hui's Cinema of the Political". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 19: 117–150 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Yau, Esther C. M. (2001). At Full Speed: Hong Kong Cinema in a Borderless World. United States of America: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 162–168. ISBN 0-8166-3234-0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Erens, Patricia Brett (2000). "Crossing Borders: Time, Memory, and the Construction of Identity in Song of Exile". Cinema Journal. 39: 43–58 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Stephen, Teo (2011). Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 137–161.

- ↑ "Minari (film)". Wikipedia. 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2023.