Course:ASIA321/2022/Leslie Cheung

Introduction

This Wiki page aims to discuss Leslie Cheung, including his life roles, screen roles, further critical analysis about his profession and contribution in the field, and his social reception. We target people who want to know more about Cheung, especially English-speaking readers, and people who want to have an academic vision and study deeper about him. As this Wiki page not only cites from websites but also includes academic peer-reviewed articles that contain different arguments, it can help readers get to know different voices surrounding Cheung. By this, we try to introduce Cheung as a three-dimensional character, making him stand vividly on the paper, not just plain text.

Biography

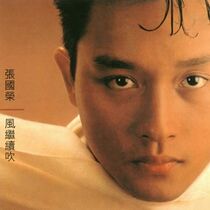

Leslie Cheung (Chinese: 张国荣/張國榮, 12 September 1956-1 April 2003) was an influential and representative figure of Hong Kong music, cinema, and popular culture from the 1980s to the 2000s. His career marked a pop culture era in Hong Kong, and his achievements in music and film made him one of the biggest stars of that era. As one of the icons of Hong Kong pop culture in the last century, his influence is limited to the local area and covers southeast Asia, Japan, South Korea, and western countries. In addition to Cheung’s career success, many people are attracted by his offscreen personality. Cheung’s sudden suicide added a tragic tone to his shining life, letting countless people sigh. Many years after he passed away, people still watch his concert recordings and movies, knowing him and remembering him. His influence continues after his death. Cheung's charming personality, cinematic and musical achievements still attract new audiences, including people born after his death.

Life Roles

As a Singer

Leslie Cheung was first debuted as a singer. As a singer, he released more than 40 music albums[1], singing in Cantonese, Mandarin, and English. From 1980 to 1990, Cheung was active in the music industry. After a brief break from music for five years, he made a comeback in 1995. Most of Cheung’s albums swept the charts and local awards, winning many of the highest awards in the Hong Kong music industry, and even gained immense popularity oversea. Cheung successfully pushed Hong Kong music to the Asia market. He created a new record for the number of concerts performed by a Chinese singer in Japan, which remains unbroken today. He was the first singer who had significant popularity in South Korea, and the album selling record Cheung made has not broken until today in the South Korean market. Cheung also held concert tours in Southeast Asia.

Moreover, Cheung’s influence on the music industry continued after he passed away. Seven years after he passed away, the special edition albums released still won the highest sales and topped the list for months in the local music chart. Also, Cheung’s accomplishment in the music industry was recognized by international media and professional musical organizations after he passed away. CNN commented Cheung as one of the most internationally influential singers in the past 50 years[2], who was the only Hong Kong artist chosen.

As an Actor

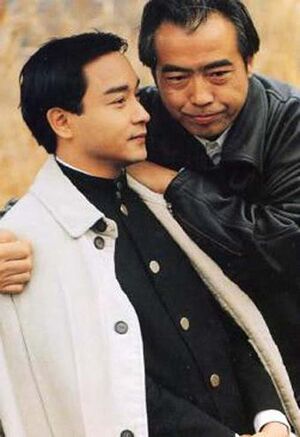

As an actor, Leslie Cheung had acted in 56 films[1] and has offered many memorable and classic screen roles that are remarkable in Chinese-language cinema, such as characters in Days of Being Wild (1990), Farewell My Concubine (1993), and Happy Together (1997). His acting won domestic and international appreciation. Cheung won Best Actor in Hong Kong Film Awards in 1991 by acting in Days of Being Wild and further gained many global affirmations. By performance in Farewell My Concubine, he solidified his position in the East Asian film industry and gained massive popularity in Japan and South Korea. Also, Cheung won the favor of the Western film industry by this film, including a Best Actor Nomination in 1993 Cannes International Film Festival, and he was invited to be a judge at the Berlin Film Festival in 1998 as the first Chinese actor. Cheung mainly collaborated with Hong Kong directors and the fifth-generation directors in mainland China. They joined forces to introduce Chinese films to Western society by telling stories with Chinese characteristics and superb acting skills. It is fair to say that thanks to the joint efforts of outstanding filmmakers like Cheung, Chinese (Mandarin) and Hong Kong films have reached a peak of development.

As a Producer

In addition to being active on screen, Cheung has also worked behind the screen as a producer. Musically, he wrote over 40 songs as a lyricist and composer from the 1980s to the 2000s[3]. Most of the songs are selected in his own album, with the rest given to other Hong Kong singers. Cheung was the joint producer of his own albums and MTV, working as a director, scripter, and editor. In total, he has co-created 12 albums and 10 MTV[3]. Besides, Cheung has jointly created several films and TV dramas in the film and television field. His job covered scriptwriting, producer, director, editor, soundtrack production, etc.

As a Senior in the Music & Film Industry

Other than expressing appreciation for the professionalism of Cheung’s work, the staff who worked with him and the younger generation in the entertainment industry praised his personality. According to interviews with directors, cinematographers, other actors, and singers, Cheung was friendly and approachable[4]. He treated everyone equally and never put anyone down. When others were in trouble, Cheung was happy to offer experience or financial help and care for people around him. He was a real gentleman. Cheung influenced many artists who later became famous, and like him, they encouraged the younger generation and treated others with courtesy.

As a Member of Sexual Minority

Meanwhile, as a public figure, Leslie Cheung openly admitted his bisexuality in an interview with magazine TIME[5], which was a very courageous thing to do in the social context of his time. In the early days, Cheung has dated several girlfriends publicly, and he had a 20-year relationship with his same-sex partner, Daffy Tong, until his death. The two had kept their relationship quiet, but Cheung also has publicly expressed his gratitude and love for his partner. In his concert in 1997, Cheung sang the song “The Moon Represents My Heart” (月亮代表我的心) for his mother and Mr. Tong on the stage[6].

Screen Roles

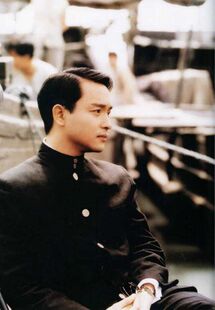

In his 26 years of acting career, Leslie Cheung has starred in 61 films (including musical films) and cooperated with many famous Chinese film directors[7]. His outstanding performances in a series of gangster, fantasy, and art-house films helped build a global reputation for Chinese cinema in the 1980s and 1990s, and he also gained international fame. The characters he played fall roughly into four categories. Cheung usually played an exuberant teenager in the early youth films, then changed to play young, more mature male characters, usually has masculine charm. After that, he performed in several queer films. His performance vividly depicts the queer characters, showing the contradictions of characters across gender. The experience of starring in queer films was the most influential stage in developing his performing arts, which led to his brilliant performing career. Lastly, in Cheung’s last films in his career, the roles he played were focused on inner emotional expression, conveying the repressed spiritual world of the characters to the audience through acting. Through these four stages, he completed the transformation from an idol actor to a professional actor.

In Days of Being Wild (1990), Cheung played a proud, rebellious young man, expressing the character’s inner world and emotional entanglements. This film is one of the most important films in Cheung’s performance career. Not only because he won the Best Actor in Hong Kong Film Awards by this film, but because this film is the turning point in his career. Using this film as a time point, Cheung shifted his career from singing to film performance, and his acting in this film finally matured enough to be recognized by the academic community[7].

Moreover, with the success of Cheung’s performance in queer or queer-related films, including playing Cheng Dieyi in Farewell My Concubine (1993), Sam Koo Ka-ming in He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (1994), and Ho Po-Wing in Happy Together (1997), with Cheung’s in real life. On the one hand, some people praised his excellent performance in the film. On the other hand, some people think as a person who has a same-sex partner, Cheung was acting himself in the film and did not need acting skills. These two opposed opinions made Cheung’s performance evaluation controversial in his artistic career[7]. As a star “whose image straddles boundaries of gender and sexual identity”[8], Cheung’s flexible gender performance onscreen and offscreen frequently challenged social taboo and traditional perceptions in China’s conservative society.

Substantive Analysis of Leslie Cheung's Profession

A Critical Analysis of A Chinese Ghost Story (1987)

We suggest that Leslie Cheung’s performance in A Chinese Ghost Story challenges the traditional gender representations in Chinese culture. A Chinese Ghost Story, directed by Ching Siu-tung and released in 1987, was adapted from Pu Songlin’s Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. The film tells the story about Ning Choi-san, a timid debt collector, who falls in love with Nip Siu-sin, a female ghost manipulated by a tree demon to seduce and devour men. With the Taoist priest Yin Chik-ha’s help, Ning Choi-san defeats the tree demon and reburies Nip Siu-sin's remains at an auspicious burial site.

We argue that while Ning Choi-san illustrates the feminine masculinity in Leslie Cheung's persona in real life, Ning Choi-san's heterosexuality contradicts Leslie Cheung's sexual orientation. In the film, the misfortune of Ning Choi-san is presented in an exaggerated, humorous way. On his way to the old temple, the troubles Ning Choi-san encounters are real concerns, such as hunger, pain, fear; however, the audiences intuitively assure that nothing too bad will happen to Ning Choi-san through Ning’s childish facial expressions and clumsy movements[9].

Leslie Cheung establishes Ning Choi-san as a comic subject to relieve the tensions of ghost horror in the film[9]. Meanwhile, Ning Choi-san’s effeminate innocence is highlighted by his comparison with Yin Chik-ha, a Taoist priest. In contrast to yin’s masculinity marked by martial arts skills and stern physical appearance, Ning Choi-san is empowered by purity and kindheartedness, which are generally attached to ideal femininity. The effeminate innocence of Ning Choi-san makes Ning a deviant hero by highlighting his moral strength. In conclusion, Ning Choi-san and Leslie Cheung's gender representations of masculinity are both tied to their romantic relationship restricted by social norms. In the film, heterosexuality is portrayed as complying with the natural order of yin and yang and leads to Nip Siu-sin's reincarnation. In contrast, Leslie Cheung's bisexual orientation brought many detractors and social pressure offscreen.

Moreover, we argue that the film's historical setting in ancient China relates to Hong Kong's disconnection from the mainland before the reunification in 1997. While mainland China underwent radical sociopolitical transformations throughout the twentieth century, Hong Kong remained relatively unchanged under British colonialism. As a result, Leslie Cheung’s feminine masculinity is recreated as an imaginary site showcasing the complexities in Hong Kong's modernity. The allusion to Pu Songlin’s book suggests and maintains the male gaze at the changing images of masculinity and femininity. However, the reimagination of masculinity and femininity in Ning Choi-san's image responds to women’s expanding roles in Hong Kong society in the late twentieth century. The ambiguity in Leslie Cheung’s gender representation parallels the anxiety regarding the impending handover of Hong Kong and the rejection of colonial cultural boundaries in the 1980s and 1990s[10].

Finally, we claim that this film's plot is related to Leslie Cheung's life experience by responding to the social pressure on his bisexual orientation. Leslie Cheung’s feminine masculinity onscreen and bisexual orientation offscreen enables him to create an imaginary temporal site where Cheung showcases the doubleness of gender representation.[11] For example, Ning Choi-san’s feminine masculinity is an alternative possibility of traditional binary gender. While sexuality differs men from women in A Chinese Ghost Story, Ning Choi-san’s abstention from sexual drive feminizes Ning’s masculinity. Ning Ning Choi-san’s characterization is associated with the romantic scholar figure, the caizi 才子, whose image in Chinese literature showcases feminine heroism[12]. As one of the most prominent celebrities in Hong Kong, the lasting longing for Leslie Cheung represents the nostalgia for the golden years of Hong Kong cinema and the collective memories of emotions associated with Cheung’s screen images.

Contribution to Cinema, Film Culture, and Beyond

We suggest that the global recognition of Leslie Cheung improved cinema’s status in Chinese culture. Leslie Cheung’s cinematic iconicity exceeds the boundary of cinema, exporting Chinese culture to the world and redefining Chineseness in the global community, especially in the West. Furthermore, we argue that as an icon of Hong Kong cinema, Leslie Cheung significantly contributed to China’s soft power in the world.

Leslie Cheung’s performing achievement was widely recognized and praised in the international society. Bey Logan, the British-born writer, filmmaker, and Hong Kong movie critic, extols Leslie Cheung’s performing achievement in his self-directed documentary Walking through the Shadows: A Tribute to Leslie Cheung. Logan describes Leslie Cheung as a "mega-star crossing the boundaries of popular music and films" and "brilliantly performing many male characters as a bisexual orientation actor"[13]. The male characters that Leslie Cheung performed varied from a traditional man of letter and traitor of a lover to a devoted opera actor and infatuated Jianghu martial artist[13]. While the diversity of Leslie Cheung’s characters reflected his performing achievement, Cheung’s performance is paradoxically viewed as expressing authentic selfhood[14]. Nevertheless, Leslie Cheung’s performance became a considerable cultural legacy.

Moreover, Leslie Cheung’s performance was considered classical and was imitated by later directors and actors. In the film A Chinese Ghost Story directed by Wilson Yip in 2010, Ning Choi-san, performed by Yu Shaoqun, learns from Leslie Cheung’s version, and Yu Shaoqun is described as “Leslie Cheung the younger”[15]. Cao Kefan, the Shanghai Media Group program host and a visiting professor at Tongji University, describes Leslie Cheung as an “actor beyond star”[16]. Perry Lam, Hong Kong cultural critic, and writer, describes Leslie Cheung as a “rare actor-author in Hong Kong cinema and the first actor using performance as the medium of self-exploration and self-redemption”[17].

In 1993, Farewell My Concubine became the first Chinese film that won the golden palm award in the 46th Cannes Film Festival; the film director Chen Kaige extols Cheung's performance, "without Leslie Cheung, there would be no Farewell My Concubine."[18] In Farewell My Concubine, the two-way mirror relationship between Leslie Cheung and Cheng Dieyi constitutes a profound artistic understanding of performance. Leslie Cheung’s charisma was included but not limited in Cheung’s films; the characters Cheung performed are attached to his labeled style to connect audiences to the emotions expressed through the films[19].

Similarly, Leslie Cheung’s achievement as a singer was praised worldwide. In 1999, Cheung gained the Golden Needle Award, the highest honor for singers in Hong Kong. Cheung became the first Chinese singer breaking the European and American singers’ monopoly of the Korean music market; his song album The Greatest Hits of Leslie Cheung made the highest selling record of Chinese songs in Korea[1]. In August 2010, in “Vote for Your Top Five Most Iconic Musicians” ran by the CNN program “Icon” in conjunction with music magazine Songlines, Leslie Cheung was listed in the top five as one of the twenty globally renowned musicians from the past 50 years along with Michael Jackson, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, and Bob Marley[1]. Therefore, we conclude that Leslie Cheung changed from a popular idol to a celebrity as a singer, whereas he became an icon of Hong Kong cinema and culture as an actor. Nowadays, Chinese cinema, actresses, and actors still learn and benefit from his legacies.

Contribution to "Androgyny" On Screen

The Use of Body

Leslie Cheung was one of the pioneer representatives of Asian queer artists with a huge fanbase, who used body symbolism to change the gender stereotypical mindset of society in Hong Kong and mainland China. He used his body to represent femininity in masculinity and masculinity in femininity, the so-called “androgyny.”

According to Sublime Eros,[11] androgyny is the “two of himself,” “heaven, and earth jammed together.” Cheung’s androgyny presented on stage and onscreen is a perfect merge of the two characteristics, and his body is the best representative of the variety of gender expressions. Ranging from his musical performance and gender cross-dressing during his musical concerts and homosexual actors in his music videos, to the male characters with passive image and gay femininity like Chan Chen Pang in Rouge and Cheng Die Yi in Farewell My Concubine, Cheung challenges the societal stereotype of gendered behaviors and the role male play on screen.

In 2002, Cheung expressed his vision of film art. He said: “I believe that a good actor should be androgynous and ever-changing.” [11] According to Woolf, androgyny unifies the mind and helps to develop one’s creativity and vitality.[11] This is seen via Cheung’s roles throughout his life. His creativity was endless, specifically regarding the topic of gender. Cheung was bold in his androgynous expressions, especially during his last concert tour – the Passion Tour in 2000. His body symbolism was shown through his cross-dressing with the help of a famous costume designer Jean Paul Gaultier. With the mix-and-match style of the outfit, they told a story of the change from an angel to a devil. It represents the journey from purity to darkness and shows Leslie Cheung's drastic change in his public image.

Looking back at the concept in his Passion Tour, we can visualize the journey of Leslie Cheung. He presented several sides of himself, the androgyny in him, but also used his body to represent the different stages in his life – the change from a fresh idol image that is widely accepted and praised by the society to a queer public figure who stands in the center of criticism. Cheung seemingly predicted his life after such a bold performance and his body symbolism as the staging involved meticulous care design.

Cheung used nearly 20 years of his career to challenge gender representation in Asian cinema and blend the stereotypical understanding of men and women on stage and screen.

Key Societal and Political Forces that Influenced His Career

Coming out into the reality

In 1992, Leslie Cheung said in an interview: “My mind is bisexual. It is easy for me to love a woman. It is also easy for me to love men, too.” [11] The release of this statement marked the start of his public LGBTQ+ image; however, this statement could also be argued as vague. It shows his flexibility in depicting different characters rather than a disclosure about his sexual orientation. The quote can be interpreted as a statement about his open-mindedness regarding femininity and masculinity representation, which indicates that he can shape various characters on screen.

Cheung did not make a clear, explicit statement about his bisexuality due to the unforeseen future of Hong Kong. From the political perspective, the anticipation of the Hong Kong handover caused anxiety in the Hong Kong community, worrying about their future after the political change. Prior to the handover, Hong Kong contained a mix of Western and Asian thinking; however, closer to 1997, the uncertainty of the potential policy change and social acceptance has created significant obstacles for Leslie Cheung to share his identity honestly.

From the social perspective, homosexuality was considered a sin and abnormality. The social standards and negative stereotypes about the LGBTQ+ community were widespread, causing low acceptance and discrimination in Hong Kong and mainland China at that time. With homosexuality regarded as a crime, Leslie Cheung’s explicit statement about his bisexuality would cause an end to his glamorous career. Therefore, he chose to talk more about his artistic blurred gender representation on screen without dragging it into his personal life.

Only in 1997, homosexuality was decriminalized.[20] in the same year, Leslie Cheung acknowledged the queer artist title by introducing his romantic partner Daffy Tong at a concert, where he presented a song “月亮代表我的心” to his lover and his mother, the two most important people in his life.[6] It is after his explicit coming out that audience tracked the record back to his quote from the early 90s and found that he has briefly mentioned his sexual orientation before.

Nevertheless, no further improvement in the legal recognition of the LGBTQ+ community was made,[20] and social discrimination continued, which caused Leslie Cheung to be at the center of criticism in the following years. More media attention focused on his sexuality rather than his cinematic achievements. In the heterocentric society, his song and music videos about two gay lovers and their intimate relationship were banned by the local biggest channel in Hong Kong and mainland China.[11] This was a setback in his career as he was not able to fully express himself in his own music work.

Reception of the Celebrity

Coming out into the Centre of Attack

After his cross-dressing on stage in the Passion Tour concert in 2000, Leslie Cheung was attacked by local media and critics. Local newspapers accused him of downgrading his masculinity in this patriarchal society by wearing feminine clothing.[11]

Moreover, a psychotherapist, Bo-neng Lee, commented that this type of behaviour is a characteristic of a mental disorder and demonstrates of Cheung’s shame and hate of his male body. Viewing Leslie Cheung’s personality, world views, and attitude towards his life, the bold action of gender crossing is conducted out of confidence and appreciation of his body.

Cheung faced massive verbal attacks from homophobic individuals and endorsed a lot of moral judgments. The bias has limited people from appreciating his creativity in artwork, and his sexual orientation entered the spotlight of criticism. Nevertheless, Leslie Cheung had a big fandom group and audiences who supported him all the way through.

Unlike the mainland Chinese reception, Leslie Cheung’s coming out earned a high prestige in Korean, Japanese, and overseas Chinese LGBTQ+ communities, and his drag performance during the Passion Tour concert was praised by Western and other Asian countries.

Coming out as an Icon

A jump from the 24th floor of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel on April 1, 2003, ended his life.

Leslie Cheung wrote in his death note that the reason behind his suicide is clinical depression. As revealed by his lover Daffy Tong after Cheung’s death, he was suffering depression for years and tried to kill himself with sleeping pills several months prior to jumping from the building.[11]

However, the topic about his sexuality and controversial personality did not stop and even escalated. The media used his death as an example showcasing the consequences of homosexuality - suicide. Some people even compared homosexuality to the SARS virus and expressed their fear that young people would be “infected” with dangerous ideologies created by the icon figure.[11] People were highly influenced by the media coverage, which formed a cause-and-effect mindset about homosexuality and suicide in them, without considering the role of social prejudice - roots of depression in LGBTQ+ community.

Apart from the media criticism right after his tragic death, the nickname “Gor Gor” (哥哥, the elder brother) given by his followers and fans after him starring in the film A Chinese Ghost Story (1987) continued years following his death. This shows their respect and appreciation for him and his accomplishments for the Hong Kong film industry and the representation of queerness on screen.

With the increasing social acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community, Leslie Cheung has been presented as an icon that challenged the gender stereotypical views back in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Nowadays, Leslie Cheung’s films like Farewell My Concubine (1993) became classics that the young generation is watching and learning from. Each year on April 1, Leslie Cheung remains one of the most discussed topics. His friends and followers show their love by dedicating social media posts and TV channels would play his films to remember him. In their interview, he is also often mentioned as an inspirational figure by film industry artists.

His stunning image has forever suspended at the age of 46 but still stays in millions of people’s hearts.

Leslie Cheung's Fandom

We suggest that Leslie Cheung’s fandom in East Asia facilitated the consumption of Hong Kong media by encouraging more international fans to engage in China’s modernity from the 1980s to 2003. For example, Japanese women’s consumption of Leslie Cheung’s fandom encourages female fans to engage in Hong Kong media and cultural modernity and become more critically aware of Japan’s modernity and imperialist history[21].

Meanwhile, in South Korea, Leslie Cheung was legitimized as “Hong Kong Film Syndrome” [22]. As an icon of masculine gender representation, Cheung revered the bias of masculinity that tied male stars to physical strength and action skills; as a result, the “beauty” of male stars was recognized and dominated the present East Asian fandom as a new visual pleasure[22]. Moreover, after Leslie Cheung’s suicide in 2003, Cheung’s expanding internet fandom allowed Cheung’s iconic presence to be extended and resonated[23].

Simultaneously, the fandom of Leslie Cheung distinguishes A Chinese Ghost Story 1987 from other adaptations of Pu Songling’s original story. According to Douban.com, many fans rewatch this film on Leslie Cheung's birthday or the suicide anniversary; they are offended by the how later adaptions and highlight how they differ from the 1987 production[24]. Leslie Cheung’s charisma creates the aura of this film as an icon of purity, persistence, and idealism[24]. Overall, Leslie Cheung represents the collective memories of the 80s and 90s generations. We claim that the popularity of Cheung’s impersonate performance onscreen and offscreen serves as an indicator of society’s aesthetic standards.

Critical Literature Review

"Forever Gor Gor, Changing fans: Leslie Cheung Posthumous Fandom Revisited" by Sabrina Qiong Yu

Sabrina Yu highlights the importance of the younger generation fanbase born after Leslie Cheung's death in 2003[4]. The article explores how the public figure gained a continuous growth of his fandom community through off-line fandom gatherings and opened a new industry of fan-entrepreneurs, who unite the fans to maintain the celebrity’s fame. Based on a case study of a Café, the author analyzes primary data they gained, which are primarily observations and interview data.

The author argues that fanbase can be full of positive energy and open to discussions of various topics like Leslie Cheung’s, which help fans to find their identity by looking up to their idol and forming their community. They also suggest that stars’ posthumous fame highly depends on their fans’ contribution, rather than the celebrity’s artistic achievements during their lifetime. It is highly applicable to many cases of dead idols as the fanbase is the key in celebrity culture nowadays.

Firelight of a Different Colour: The Life and Times of Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing by Nigel Collett

In this monograph, Collett discusses the whole life story of Leslie Cheung, from his birth to death. By introducing the social and historical context of Hong Kong in the last century, Collett shows how Cheung’s individual life shapes by the large environment and how he influences back after getting famous. He discusses Cheung comprehensively, including his career development and private life, which is a firm reference for us when writing this Wiki page, as we also need to include these aspects.

"Leslie Cheung: Star as Autosexual" by Julian Stringer

Stringer mainly focuses on Leslie Cheung’s “polysemic polysexuality”[25]. She uses the video recordings like documentaries, reality shows, and Cheung’s works to analyze Cheung’s onscreen and offscreen sexuality. By discussing three-dimension of Cheung’s media persona, including his notions of privacy, his star image is highly sexualized nature, and the connection between his image with screen roles, she claims that Cheung “transcend narcissism and androgyny by taking these qualities into the self-enclosed world of the autosexual”[26]. This article inspires us to know the relationship between Cheung himself and his screen roles and dig the sexual projection and resonation on each other, which gives us a deeper understanding when we write about him.

"A Chinese Ghost Story: A Hong Kong Comedy Film’s Cult Following in Mainland China" by Hongjian Wang

In this article, Wang explains how the comedy film A Chinese Ghost Story (1987) generated a phenomenal cult of Leslie Cheung in mainland China. Wang aims to understand the relationship between comedy film and cult film; he analyzes the comic dialectics and audience responses to the film on Douban.com to explore how Leslie Cheung’s cult develops in mainland China[27]. He argues that the “post-80s” constitutes the core of the film’s cult, and the film's half-seriousness serves as the foundation of the cult following[27]. This article is a critical reference to Leslie Cheung’s celebrity identity as an example of Cheung’s screen role and how Cheung’s onscreen and offscreen images mirror each other.

"Camp Stars of Androgyny: A Study of Leslie Cheung and Anita Mui’s Body Images of Desire" by Natalia Siu‐hung Chan

Natalia Chan interrogates Cheung’s gender performativity in Hong Kong popular culture. She examines Cheung’s cross-gender identity and intersexuality in music videos, androgynous dressing and make-up in concerts, and the multiple images of his male femininity in films[28]. Chan’s purpose is to investigate the body politics, the sexual identity, and the gender performativity of Leslie Cheung as the cultural memory of Hong Kong[28]. Chan argues that Leslie Cheung’s stage performances and music videos demonstrate the artistic vision that blends the male and female bodies, and Leslie Cheung’s clothing serves as a medium to transgress gender boundaries, challenge conventional norms, and establish a new fluidity of sexuality[28]. This article is an important reference to Leslie Cheung’s celebrity status in Hong Kong’s cultural and geographical context.

Critical Debates

Interpretation of His Death

The public has expressed their contradicting interpretations of his death. The perspectives significantly differ with age. The younger generation, who did not know Cheung while he was alive, and the sociopolitical context he lived in, would have a different understanding of his death. It is now widely accepted that Cheung died because of clinical depression. However, the reason for his depression is still in a hot debate.[29]

Some people say that he committed suicide because he was getting old and cared a lot about his physical appearance. While others disagree, saying he wanted to age gracefully and was not afraid of aging. [29] They claim that the main reason for his death is the negative comments after his gender-crossing Passion Tour concert, after which he was heavily criticized by the media and public.

There may be various factors contributing to the development of his depression, including social pressure regarding sexual orientation and hostile reception from society.

We will never know all the factors that contributed to his depression, but at least through the critical debates we engage in with strangers via digital media, we can view him from different perspectives and learn new lessons about the inner self, gender stereotypes, and social norms in the modern society. Potentially, these debates may find solutions to help people struggling with mental illness.

Conclusion

Overall, we introduce and analyze Leslie Cheung in this Wiki page in different aspects, emphasizing his contribution and controversy. As a super icon active in the last century, Cheung represents the Hong Kong pop culture’s developments and decline. By reading through his works, we can see the best stage performance, albums, and films in that era. Furthermore, in the previous analysis, Cheung promoted Hong Kong pop culture to Asia and even the global market so that more people could hear the voice of the East and know more about China through his works. His contribution is long last to today that many people nowadays still watch his film to understand Chinese society and culture.

The most significant controversy among Cheung is the gender issues. His bisexuality and cross-dressing in performance was a break of the contemporary social taboos. His body image in performance was subject to various interpretations and speculations, not all of them benign. The research about Cheung is mature, especially deconstruction about his queer screen roles and stage performance. It would be inspiring if people discuss Cheung’s position as a pioneer or other roles and when writing about the LGBTQ culture development in East Asia pop culture.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Leung, Helen Hok-Sze (2008). "In Queer Memory: Leslie Cheung (1956-2003)". Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 65–130. ISBN 978-0-7748-1469-0. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":4" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ "Leslie Cheung and Teresa Teng are nominated as CNN musicians". Sina Music. 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Baike-Zhang Guorong". Baidu.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Yu, Sabrina Qiong (2021). "Forever Gor Gor, changing fans: Leslie Cheung posthumous fandom revisited". Celebrity Studies. 12: 187. doi:10.1080/19392397.2021.1912096.

- ↑ "Forever Leslie-TIME-Flash Player Installation".

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Leslie Cheung [月亮代表我的心] 跨越97演唱会-Youtube".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Zhou, Y. (2015). Leslie Cheung’s Movie Performing Arts Research. Master’s thesis, Fujian Normal University. China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

- ↑ Stringer, Julian (2010). "Leslie Cheung: Star as Autosexual". In Farquhar, Mary; Zhang, Yingjin (eds.). Chinese Film Stars. London: Routledge. p. 210.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wang, Hongjian (2018). "A Chinese Ghost Story: A Hong Kong Comedy Film's Cult Following in Mainland China". Journal of Chinese Cinemas. 12 (2): 146. doi:10.1080/17508061.2018.1475968.

- ↑ Woodland, Sarah (2018). Remaking Gender and the Family: Perspectives on Contemporary Chinese-language Film Remakes. Leiden: Brill. p. 80.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Yau, Ching; Chan, Natalia (2010). "Queering Body and Sexuality: Leslie Cheung's Gender

Representation in Hong Kong Popular Culture". As Normal As Possible. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 133–149. ISBN 9789882205727. line feed character in

|chapter=at position 53 (help) - ↑ Woodland, Sarah (2018). Remaking Gender and the Family: Perspectives on Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes. Leiden: Brill. p. 86.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chou, Katherine Hui-ling (January 2009). "The Queer Stardom and Body Enactment of Leslie Cheung". Journal of Theater Studies. 3: 218.

- ↑ Chou, Katherine Hui-ling (2009). "The Queer Stardom and Body Enactment of Leslie Cheung". Journal of Theater Studies. 3: 218.

- ↑ Mandarin Films Limited (22 June 2010). "Yu Shaoqun: Don't Call me Leslie Cheung the Younger". Mandarin Films Limited. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ↑ Cao, Kefan (30 November 2018). "Memories of Leslie Cheung: Actors Beyond the Stars". Xinmin Weekly. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ↑ Zhuang, Jun (2012). "Uninhibited and Affectionate: Leslie Cheung's Artistic Life". Yin Yue Shi Kong. 1 (4): 134–137.

- ↑ "Chen Kaige: Without Leslie Cheung, there would be no Farewell My Concubine". Sina. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ↑ Chou, Katherine Hui-ling (January 2009). "The Queer Stardom and Body Enactment of Leslie Cheung". Journal of Theater Studies. 3: 217–248.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Mountford, Tom (Summer 2009). "The Legal Status and Position of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in the People's Republic of China" (PDF). OutRight Action International Organization.

- ↑ Chin, Bertha; Morimoto, Lori Hitchcock (May 2013). "Towards a Theory of Transcultural Fandom". Journal of Audience and Reception Studies. 10 (1): 95.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lee, Hyung-Sook (2006). "Peripherals Encounter: The Hong Kong Film Syndrome in South Korea". Discourse. 28 (2/3): 102–103.

- ↑ Stringer, Julian (2010). "Leslie Cheung: Star as Autosexual". In Farquhar, Mary; Zhang, Yingjin (eds.). Chinese Film Stars. London: Routledge. p. 207.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Woodland, Sarah (2018). Remaking Gender and the Family: Perspectives on Contemporary Chinese-Llanguage Film Remakes. Leiden: Brill. p. 151.

- ↑ Stringer, Julian (2010). "Leslie Cheung: Star as Autosexual". In Farquhar, Mary; Zhang, Yingjin (eds.). Chinese Film Stars. London: Routledge. p. 209.

- ↑ Stringer, Julian (2010). "Leslie Cheung: Star as Autosexual". In Farquhar, Mary; Zhang, Yingjin (eds.). Chinese Film Stars. London: Routledge. p. 211.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Wang, Hongjian (2018). "A Chinese Ghost Story: A Hong Kong comedy film's cult following in Mainland China". Journal of Chinese Cinemas. 12 (2): 142. line feed character in

|title=at position 49 (help) - ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Chan, Natalia Siu‐hung (2015). "Camp Stars of Androgyny: A Study of Leslie Cheung and

Anita Mui's Body Images of Desire". In Cheung, Esther M.K.; Marchetti; Gina, Esther C.M. (eds.). A Companion to: Hong Kong Cinema. Massachusetts: Wiley Blackwill. pp. 341–342. Unknown parameter

|last name of third editor=ignored (help); line feed character in|chapter=at position 54 (help) - ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Why did the Hong Kong singer, actor Leslie Cheung commit suicide?". Quora.

Sharing

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA321. |