Course:ASIA319/2022/"Complex" (控)

Introduction

Complex (控) in Chinese, is a term that originated from Japanese subculture and became widely adopted in modern Chinese popular culture to express a strong uncontrollable desire or preference for a certain subject. The phonetic sound, Kòng 控, serves as a phonetic rendering of Japanese kon コン and ultimately represents a shortened form of the English word, "complex"[1]. The term “complex” is derived from psychology and is used to describe a “knot in the unconscious” of one's feelings and beliefs that make it difficult for other people to understand. It can be used to identify someone's mental state towards a certain subject in which they may experience a strong unconscious conviction, obsession, impulse, or addiction. As such, kòng 控 has become a highly productive Mandarin suffix signifying "-com(plex)” that is used at the end of other nouns[1]. By extension, the kòng 控 is a suffix that can be be used in the sense of "nerd /fan /-phile / maniac".

In the past, the word Kòng 控 original and literal meaning meant control. This word was used in everyday ordinary life to politics as it revealed the dichotomy between the views of the government and the people[1]. As a bound morpheme, it is attached to other words such as dominate kòngzhì (控制), manipulate (cāokòng 操控), program controlled (chéngkòng 程控), criminal charges (kòngzuì 控罪), and controllable (kěkòng 可控). As listed, the word Kòng 控 has many negative connotations attached to it. Hence why it is associated as a government-related word that emphasizes control of society. When ordinary people use the word, it is commonly used to describe how the government controls citizenry, internet, and society. However, over time, the word has transformed to be more commonly recognized for its phonetic sound and resemblance to the Japanese word, kon.

Today, it is a popular word that many people use to express their passions when verbally communicating. To use the word in a phrase, people often add it after a noun containing what the person is unconsciously drawn to. It is most commonly used to express people’s obsessions with unconventional and odd hobbies. In English sentence structures, people would say “I have a complex about watching Chinese dramas” or “ I have a Chinese drama complex”.

Chinese Origins and Definitions in Chinese History

If we chase back the roots of the word 控, we can see a range of meanings it represents. Therefore, we can visualize the path it has from ancient use till its present utilization. For simplicity, I will use Kong to represent the word 控 in the following description.

- Kong, to open the bow, or draw the bow. — <说文>

- To draw something with strength.

- The soldier used to draw the bow to shoot the arrow.

- To drive the animals.

- To drive the horses. —— Dong Xieyuan <West Chamber> 董解元《西厢记》

- To drive the livestocks.

- To hold the reins (Chinese modern dictionary). (勒马,赶牲畜)

- To hold the reins in order to control the horse.

- To throw. (投)

- To cast something in a direction.

- To appeal,.(申诉)

- To accuse the case.

- To complain.

- To make accusations.

- To hang. (悬)

- To hang something at a certain height.[2]

Glossary of Explicit Contemporary Dictionary Meanings

Above all are a few historical meanings of kong. It would be quite confusing and strange to see them in modern usage. As time has passed, Kong has been evolving accordingly. The original meanings have been distorted and twisted to accommodate contemporary usage. Listed below are contemporary definitions associated with kong.

- To state[3] (申述,告诉)

- To tell.

- To make a representation.

- To condemn

- To present the victimization or the facts of the victimization to the relevant authorities or the public, and to request legal or public opinion sanctions against the perpetrators

- To control purchase

- Control social group purchase

- Holding company

- Proprietary company

- A company that owns all or part of the shares of another company

- Control

- To hold the object from arbitrary activities or beyond the scope, to manipulate;

- To bring it under one's own possession, management or influence, to move according to the will of the controller.

- Cybernetics

- The study of the general laws of control and communication within animals and machines, focusing on the mathematical relationships in processes.

"An English word for 控(kong)?": Western Cultural Context and Historical Emergence

The plain meaning of kong is “control” — a polysemous word with multiple meanings. In the Chinese cultural context, its usage usually coincides with and recalls associations with ACGN culture.

ACGN is an acronym for animation 动画, comic books 漫画, games 游戏, and novels 小说. When trying to understand whether or not there is a cultural counterpart in Western culture or non-Chinese cultures, it is important to distinguish the unique aspects of kong that are not similarly captured in other counterparts. Specifically speaking, when referring to kong in the Chinese context in opposition to attempting to capture the same meaning within English.

At first glance, kong and its commonly used associations could conjure up connotations with English words like 'fetish' that have more negative connotations. For example, a search on Baidu 百度, under its list of common classifications, yields descriptions such as “Beast ear control, refers to a sexual orientation of a person to a girl or a royal sister with orc-like ears”[4]. Additional descriptions include “Sister Royal Control, meaning a special preference for young adult women” or “Maid accusation, referring to a sexual orientation in which men and women have a more sexual interest in maids”[4]. While these descriptions seem to match with associations to the word “fetish” in English-speaking societies, the meaning is not a one-to-one accurate translation.

The Western Cultural Context and Difficulties of Translating 控 into English

Why does fetish not accurately capture kong as a counterpart translation? It is partly due to differing connotations of fetish in Western society in contrast to the connotations of kong in Chinese society. In the West, fetish has associations of sex or taboo-like qualities — both of which have generally negative connotations in the West. On the Collins dictionary website, 'fetish' is defined as “if someone has a fetish, they have an unusually strong liking or need for a particular object or activity, as a way of getting sexual pleasure” [5]. However, it is only quite recently that fetish imagery and discourse have become more widely spread. This can be attributed to the release of films like Fifty Shades of Grey. Searches for the term “BDSM”, widely regarded as a sex fetish in Western society, actually spiked in the same month that Fifty Shades of Grey was released in theatres[6]. It becomes clear that while kong may be used, for example, to describe “preferences for young adult women” or maids, kong does not conjure similar sex-related or taboo connotations as the word fetish in Western society.

While the connotations between fetish and kong are not the same within their respective cultural contexts, the word fetish and its origins inform us that, like kong, the desire to invest objects or things with affection is similar between the two words. Massimo Fusillo states that “objects transform themselves into things endowed with an excess of meaning, invested with affections, symbols, memories, and illusions”[7]. This is part of the transformation process that occurs when fetishizing something or when kong is attached in combination to other objects, concepts, or aesthetics.

Historical Tracing of the Emergence of 'Fetish'

However, the meaning of fetish emerged from a colonial and violent history, which is not replicated in kong. 'Fetish' emerged as a process to understand the “other”, which extends from the Western history of violent colonization and the process of European enlightenment in response to discovering that there existed other cultures, nations, and peoples, who lived in ways that differed from their own. It is in this way that “reflection on the fetish originated in colonialist culture and thus was initially a gesture of aggression, but it soon expanded its focus to all forms of alterity, especially the problem of the internal other, entailing in turn the examination of one’s ancestral past, one’s impulses, and the alienation created by modernity itself”[7].

The issue of this violent, colonial-centred origin of fetishism as well as ‘control’ in the Western context is also explored by the late renowned political philosopher, Edward Said. His analyses are particularly poignant in understanding the history of Western views of Eastern culture and society. He brings to light the existence of the orientalist imagination as a way to subject colonized peoples to a level of Western control in the form of colonialism. By controlling the stories people are told about themselves, this in and of itself constructs deeply ingrained notions of inferiority within colonized populations. The perpetuation of these orientalist stories effectively controlled and fetishized the East. In the context of an ever-expanding West, this control helped create narratives to justify colonial expansion. For example, “consider that in 1800 Western powers claimed 55 percent but actually held approximately 35 percent of the earth’s surface… By 1914 — Europe held a grand total of roughly 85 percent of the earth as colonies, protectorates, dependencies, dominions, and commonwealths”[8].

控kong does not contain this associated historical context, but in attempting to define a Western translation of kong, the Western histories of control through colonialism and fetishization of Eastern regions need to be acknowledged.

Internet Fan or 'Stan' Culture as a Translation of 控

Another significant difference between kong and an assumed translation into English is that kong is a complex word that captures many disparate meanings. For example, kong contains meanings of addiction, accuse, enthusiast, devotee or -phile[2]. Additionally kong has an element that can soften or ‘casualize’ the tone of the word it is in combination with. Like in the case of “Big breast control”, the addition of kong helps to lighten the tone of the word’s meaning — in a way that ‘addict’ or ‘devotee’ cannot.

What word(s) can then capture this similar aspect of lightening the tone of an addiction or devotion to something? In English and popular culture-speak, the word “stan” or stan-culture and “fan” can capture this aspect. In recent years in English-speaking societies, the lexicon surrounding “stan” and stan-culture has emerged on forums and pages. The phenomenon of “stan pages” has emerged which refers to pages on Instagram or Twitter that are dedicated to praising a specific celebrity or even group of people. Here, the word stan helps to lighten the tone of what might be more sterilely referred to as celebrity worship. Salient examples of this stan-culture are best found on popular live-update social media platform, Twitter.

One strong example of this celebrity worship or stan-culture is the worship of Nicki Minaj, a popular Black female rapper. @hotminaj on Instagram is a popular stan page which has been endorsed by Nicki Minaj as proclaimed by the page’s bio[9]. At the time of writing, the @hotminaj account has over two-hundred thousand followers on Instagram. Additionally, searching the hashtag “barbz”, the nickname for Nicki Minaj fans, on Twitter yields hundreds of tweets with hundreds of likes. It is through the medium of social media, and more broadly, the internet, that has yielded a level of anonymity allowing for public celebrity worship without the risk of social ostracization for being “weird.”

'Stan' culture surrounding Nicki Minaj and other celebrities also reoccur on platforms other than social media. Popular video-sharing website, YouTube, has become a host to many 'stan' videos of various celebrities. The typical stan video uploaded on Youtube is 10 to 15 seconds in length. This short video length is usually the result of exporting short videos uploaded on Twitter, before propagating them on YouTube. The video linked below is titled Stan twitter: Nicki Minaj “barbz stay in school".[10] The title references 'stan twitter' as the source of the video, and the title also uses the Nicki Minaj fandom, 'barbz.' At the time of writing the video has close to 750 thousand views and about 1500 comments — a significant amount of engagement for a 14-second clip. The immense 'stan' engagement is not limited to this video, as a YouTube search for "Stan Nicki Minaj" brings up dozens of videos, often 10-15 seconds in length with hundreds of thousands of views.

Video: Stan twitter: Nicki Minaj "barbz stay in school"

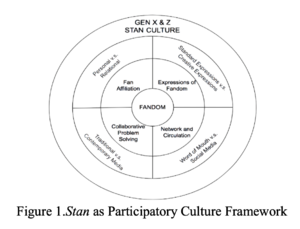

Contextualizing and Problematizing 'Stan' Culture

In recent years, 'stan' culture has entered the online social media discourse. Wide-ranging fan bases covering various artists have sprung up, creating platforms for community construction and a sense of connectedness with other like-minded people. A study from on Filipino stan culture using a framework of generational analysis found key differences between Generation-X stans and their Generation-Z counterparts. Their study found that between the two generations, fan or stan interactions by Generation-Z utilized social media more than Generation-X stans. While Gen-X stans limited their fandom to their families and close friends, Gen-Z stans and fan groups gained connections from fellow fans all over the world who also idolized the same celebrities.[11]

Concerning forms of expression of stan-culture, Gen-X stans generally use traditional media and word of mouth rather than internet-based expressions. On the other hand, Gen-Z stans, in addition to using social media to express idolization, were also found to create fan art or fan fiction as well.[11] However, these additional means of fan expression, while seemingly liberating, can be seen as an expansion of emotional labour — in which fans might have to spend more of their own time, and even money, to participate in the fandom and its associated economies.

Henry Jenkins defines a 'participatory culture framework' as a culture:[12]

- Has relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement

- Has strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations with others

- Has some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices

- Members believe that their contributions matter

- Members feel some degree of social connection with one another (at the least they care what other people think about what they have created).

It is through the 'participatory culture framework' that "stan" culture can be understood.

"Complex (控)" Within Japanese Culture

Linguistic Emergence of "コン(Kong)" in Japan

The Japanese pronunciation of "コン(kon)" is derived from the English word "complex", which in psychology refers to a complex, such as the Oedipus complex. The word "con" refers to a person who is extremely fond of something or likes something extremely. When "コン(kon)" is used as a noun, the word "kon" precedes the word "like", e.g., ロリコン(rorikon)[13].

Complex as Adapted from Western Psychology Theories

In Japan, Freudian psychoanalysis was introduced as a psychological and psychiatric theory along with the introduction of Western medicine. In Freud's psychoanalysis, the "Oedipus complex" occupied as a centra conception[13]. However, psychoanalysis, which was also a theory of the dynamics of the conscious and unconscious mind, was not familiar to the Japanese people at the time, and generally, the theory did not circulate. After World War II, Alfred Adler's personality psychology was introduced to Japan from the United States. At the time, Adler's theory centred on the inferiority complex. Adler's theory, which held that personality development is established through the overcoming of the inferiority complex. The concept seemed to be familiar to the Japanese. In postwar Japan, Adler's theory was more widely accepted in comparison to Freud's theory. The central concept of his theory, the "inferiority complex," became more prevalent. In Japan, the term "complex" still tends to refer implicitly to the inferiority complex. Since fetishism is almost synonymous with complexity in analytical psychology, the term complex is also sometimes used in the field of fetishism. Although "fetishism" is a slang term rather than a psychological term, it is not conceptually incorrect. In this case, it means precisely a complex that is evoked by a certain fetishism.

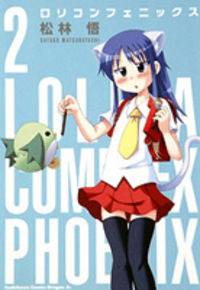

Complex Within ACGN Field; Its Connection With Chinese Popular Culture

ACGN is the combined abbreviation of animation, comic, game, and novel. Is a new term expanded from ACG (anime, comic, game), mainly popular in Chinese-speaking culture. Since the traditional scope of ACG has long been insufficient to cover the modern youth culture and entertainment fields, the term ACGN was derived with the addition of light novels and other postmodern literary works. In ACGN culture, the word "control" is used as a suffix to refer to an excessive preference or obsession for a specific object[14]. For example, when the object is "ロリータ (rorita)", it is called "ロリコン (rorita, lolita control)" in Japanese. The emerge of lolita complex style anime is also popular not only in Japan but also worldwide[15]. Among ACGN culture, novels usually refer to light novels, but with the increasing number of online literature adaptations of ACG works, the section of novels can also be used to refer to literature with a high degree of acceptance in the ACGN circle in general. ACGN-related content has formed a complete business chain on the Internet and is enjoyed by more and more Internet users as a way of entertainment, through web light novel websites, games, and animation. The products covered by it have formed a huge business opportunity on the Internet, and are more popular in Japan and China (including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). Especially in Japan, where anime and games are constantly developed on the basis of ACGN and are highly popular all over the world.

Social, Cultural, and Political Problems

Furthermore, the word Kong has expanded its literal meaning and extent to be discussed from ordinary life to politics. What I am about to illustrate are several Chinese phenomena under the meaning of control.

The Chinese Movie Industry & Censorship Control:

China has the largest film market in the world, it beats America in 2020 and secured the number one seat of box offices in the league. The blockbuster “The battle at Lake Changjin” swiped over $900 million in the domestic market. The point here is not to talk about the thrilling records that the movie has achieved. Much of the success has something to do with the government’s propaganda promotion. The party has been craving for a movie that could emotionally lift audiences, as past attempts had been criticized as dull.

Despite the close association with film industry workers, the Chinese government had published its grand map to make it more appealing. A five-year plan started from 2021 to 2025 to release 10 major films per year. The project itself comes with strictly imposed censorship control. Any words or claims that could potentially hurt or endanger the party’s regime, will be banned — which could lead to a complete ban of the entire movie. The production company or the director may face heavy punishment, like exile from the industry or erasure of their name from mainstream sources.

Another point worth noting is although the party endorses patriotic films, the quality of the film has to meet a minimum standard. There have been precedents of banning superficial or idiotic patriotic movies and dramas, with the aim being to set a benchmark for filmmakers and to ensure a generally positive public reception. The word “complex” can also be interpreted in the way high tables protect domestic fruits from decaying on the outside. The state administration of the press will limit spaces available for foreign film releases to make sure that state and local movies get their expected share. Such a sanction has led to a re-calculation from entertainment giants like Disney and Sony, each of which has had to re-evaluate the viability of their films in the Chinese market.

(Economist, “How Chinese propaganda films became watchable")[16]

Study Resources, Inequality, and Imbalance

China has the largest population on the planet but is relatively scarce on study resources. Therefore, to balance such imbalance, the idea of xuequfang emerged. It stands for the meeting “house near school” in Chinese. In China, can money grant you happiness? Maybe, but can money grant you a seat at the finest school? Not really. The phenomenon started with government-sponsored relocation projects. The policy moved some families to leave from the central area where top league schools blossomed and relocate them to suburban areas. The anxious parents feared that they would lose the accessibility for quality education. As a result, some chose to purchase property near their obsessed schools.

Firstly, let’s read some statistics. Take the example of Yuetan school, one of the top-tier schools in the district. The access requires residency in a nearby area, where housing prices soared about 58% higher than an ordinary condo.[17] In other words, despite the Compulsory Education policy, Chinese parents are still paying the premium to ensure their children’s future. The situation is a two-bedroom apartment open to take down with a cost of 3.6 million,[18] twice higher than the intermediate apartment in the U.K.

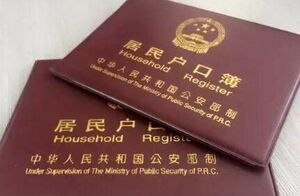

户口Hukou and 控kong

In addition to intense scarcity regarding study resources, there’s another barrier confronted by the citizens — the household registration system, Hukou. The government set up an iron solid policy on the city residents to enjoy the social welfare and education resources within a certain area. The Beijing hukou gives people the stability of living and working in a first-tier city, but it also somewhat cuts off the possibility of moving to a new city.

Below are some comments from new residents who are new to Beijing and looking for a new life.

"I know a client who spent 120 W to get his child a Beijing residence for a recent graduate."

Why is a Beijing hukou so valuable?

"Some people say you have a Beijing hukou to enjoy first-class Beijing,"

[19] Below are the pre-requirements to get a Hukou in Beijing, and remember, meeting those requirements doesn't ensure applicants will be successful.

1. Academic talent: full-time undergraduates not more than 40 years old, master students not more than 45 years old, doctoral students are not subject to age restrictions.

2. Skilled talents: graduates of higher vocational colleges and work in Tianjin for one year, or graduates of secondary vocational colleges and work in Tianjin for three years, not more than 35 years old, with higher vocational qualifications; not more than 40 years old, with technician vocational qualifications; not more than 50 years old If you are not more than 50 years old, you have a higher vocational qualification as a technician;

3. Qualified talents: with associate senior titles and above, as well as with domestic and foreign actuaries, certified public accountants, certified tax accountants, registered architects, lawyers and other practicing qualifications[19]

The Hukou idea originated in the Qin Dynasty, and it was created to limit the movement of people using limited resources in order to facilitate control. This was matched by the "baojia" system, which is now known as the street system, but the lack of a baojia system weakened the control of the hukou system. After the founding of the country, it had a positive effect on the rapid stabilization of security and the concentration of resources in large cities and industries.

Conclusion

In the past, the word “Kòng 控” had many negative and taboo connotation in Western, Japanese, and Chinese culture as it was commonly associated with controversial addictions, personality psychology, and government control over society. However, the word has transformed to a more neutral meaning over time that captures an expression of a person’s obsession with unconventional and odd passions in Chinese popular culture. Of its many meanings, the one that has been extended from its colonial, controversial, and violent history is the strong desire or devotion towards something. Today, the addition of kong is used to soften or casualize the word it is in combination with when partaking in ‘popular culture-speak’ in which one enthusiastically ‘fangirls/fanboys’ about a certain subject they are very interested in. For example, one might say “I am a huge Rap of China Kòng 控” in a sentence. It is a very versatile word that can be added to the end of anything. Words that may be synonyms include ‘fan’ and ‘stan’. In Chinese popular culture, many people use the term by naming what shows, books, movies, photos, concerts, or music they like and adding the suffix Kòng 控 after it to reflect their strong feelings of interest towards it. It is most commonly used in association with subjects related to ACGN where many people gather and form communities to celebrate their interests in particular subjects.

Overall, “Kòng 控” is important to Chinese contemporary popular consumer culture in bringing together people who share common interests to form the foundation of a fandom. Specifically, “Complex Kòng 控” contributes to helping fans develop their own fan identity and other meaningful aspects of their cultural and self identity. John Fiske[20] does very well to explain the concept on how fans work to accumulate “fan cultural capital” to learn the ins and outs of the object of their fandom to be able to fully appreciate it and become accepted as a part of a fandom. In developing this identity, fans become slowly invested and form an affective relationship with the subject of their passion by partaking in socially organized fan activities, conventions, clubs, attend live events, or post on online fan message boards. As fans participate in communal fan cultures and activities, they develop a stronger attachment overtime and self identity with the fandom. Within fandoms, some fans are recognized and are known as “subcultural celebrities” through gaining the respect and recognition by many others in their fandom for demonstrating their dedication in performative consumption.[20] Given this context, some fans who partake in performative consumptions are in ways both highly self aware and unaware as they are able to recognize their obsession but unable to account for why they became fans in the first place and pinpoint what is fuelling their addictions.[21] Hence, “Complex Kòng 控” raises awareness to this phenomenon very well as there is more research that needs to be done in terms of the psychology behind the fan identity complex that operates below the level of discursive consciousness.[21]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Mair, Victor (December 17 2011). "Morpheme(s) of the Year". Language Log. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 "控 Synonyms, Antonyms - MandarinChinese-English Dictionary & Thesaurus". Yellowbridge. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "控". Baidu Baike. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Control (ACGN Terminology)". Baidu. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Definition of 'fetish'". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "'BDSM': Google Search Trends". Google Trends. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fusillo, Massimo; Simpson, Thomas (2017). The Fetish: Literature, Cinema, Visual Art. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc. pp. 1–18.

- ↑ Said, Edward (1994). Culture and Imperialism. Vintage; Reprint edition. p. 8. ISBN 0679750541.

- ↑ "Nicki Minaj Fan Account (@hotminaj)". Instagram. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Stan twitter: Nicki Minaj "Barbz stay in school"". YouTube. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bermudez, Rhicki; Cham, Kimberly; Galido, Leila; Tagacay, Karen; Luis Clamor, Wilfred (2021). "The Filipino "Stan" Phenomenon and Henry Jenkins‟ Participatory Culture: The Case of Generations X and Z" (PDF). Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences. 7: 1–7 – via Research Gate.

- ↑ Jenkins, Henry (2009). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for 21st Century. The MIT Press. ISBN 0262513625.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "コンプレックス". コトバンク. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ↑ "ACGN". Baidu. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ↑ Hinton, Perry R (2014). "The Cultural Context and the Interpretation of Japanese 'Lolita Complex' Style Anime" (PDF). Intercultural Communication Studies XXIII: 2: 54–68.

- ↑ "How Chinese propaganda films became watchable". The Economist. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Property and assets". KE holdings. 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Local experts, local knowledge". Localagent Properties. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Why does everyone want a Beijing Hukou? (trans.)". Zhihu (知乎). Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hills, M (2004). "Defining Cult TV: Texts, Inter- Texts and Fan Audiences". In: Allen, R. C. & Hill, A. (Eds.), The TV Studies Reader. Routledge, New York and London,: 509–23.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Harrington, C. L.; Bielby, D. (1995). Soap Fans: Pursuing Pleasure and Making Meaning in Everyday Life. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA319. |