Course:ASIA319/2020/宅 (otaku)

Overview

Otaku, 宅 (zhái) in Chinese, is a term originated from Japan and is widely adopted by contemporary Chinese culture. Since it entered the Chinese space in the 1980's, it has developed various usages and connotations –– from being unique to Chinese culture to overlapping with international interpretations. Recurrent usages of 宅 (zhái) include referring to obsessive anime fans and people who engage in little social interactions. Furthermore, otaku subculture, common in China and academic discussions, is highly correlated with China’s contemporary social, political, and cultural issues.

Introduction

Otaku is a Japanese term that refers to people who are knowledgeable, skillful and enthusiastic about anime, comics and video games. Since spreading to China, the word otaku has adopted a much broader meaning. Subcultures such as "military otaku" (军事宅 jūn shì zhái), "gaming otaku" (游戏宅 yóu xì zhái), "computer otaku" (电脑宅 diàn năo zhái), and "technology otaku" (技术宅 jì shù zhái) have been established overtime as more and more people have categorized themselves into these subcultures according to their interests. "Anime otaku" (御宅族 yù zhái zú) is the most used otaku-related term in China and is also the first type of otaku that was introduced to the Chinese space and continues to embody the most negative connotations amongst other otaku subcultures. This is mostly due to anime otakus' addiction and commercialization of the virtual world which are considered potential risks that negatively impact youth's physical and mental health.[1] In post-socialist China, Bilibili is the largest ACGN (Anime, comics, games and novel) social media platform that provides its users an environment that allows them to examine and maintain their repressed subjectivity.[2] The complicated interaction between consumers and digital technology is a significant element that contributes to the formation of otaku subcultures. Driven by "participatory culture," the internet where Chinese otakus gather has created a diversified mode for communication by helping young people obtain a cultural capital.[3] Because of the ambiguous Chinese meaning of otaku (宅 zhái), the term has been representing new values, life attitudes, and localized cultural meanings accepted by the younger generation of China. Here, we examine how the keyword, otaku is utilized, commercialized, and popularized in contemporary societies.

Etymology of Otaku (宅 zhái)

Today, the character 宅 (zhái) is commonly used to translate the Japanese word: otaku to Chinese. Before the adoption of the contemporary meaning of otaku, the term was used to refer to ‘your house’ (お宅) as well as ‘you’ in Japanese honorific speech.[4] The second character of ‘your house’: 宅, is the kanji for taku which means house in Chinese and Japanese and is written in the same way in both languages. In the modern Japanese dictionary, Kōjien, otaku is defined as: “People who are interested in a particular genre or object, are extraordinarily knowledgeable about it, but are lacking in social common sense."[5] Regarding this contemporary definition, otaku is commonly written as おたく (hiragana) and オタク (katakana).

In the 1983 magazine issue, Manga Burikko, columnist Nakamori Akio was reputedly the first person to use otaku to refer to certain groups of people in Japan instead of using it to mean ‘you’ or ‘your house.’ In his article, おたく』の研究 ("Otaku" no Kenkyū), Nakamori described the participants of Comic Market as otakus.[6] However, this meaning of otaku was not popularized until ‘The Otaku Murderer’ case when Miyazaki Tsutomu was arrested for kidnapping and murdering four girls in 1989. At the time, the Japanese media declared Miyazaki as an otaku and stressed his frequent visits to Comic Market and emphasized his enormous manga collection.[7] Since Miyazaki’s case, there has been the perception that otakus are members of specific subcultures and is overall seen as a form of anime and manga cult fandom.[8] Further definition of otaku refers to those who are obsessed with subcultures such as games, computers, figurines, and science fiction and are people who project their objects of love through fictionalizing them in cosplays and purchasing subculture-related merchandise.[9] Otaku is also used to describe those who have poor interpersonal skills and hoarding tendencies regarding their subculture but can also be used proudly to identify one’s obsession over anime.[10]

Genesis of Otaku

In the early 1980s, before the spread of the term otaku, people in Japan used the derogatory term “ビョーキ”, (byoki, 病気) to refer to game and anime lovers.[11] When Japan experienced the explosive development of the animation industry in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, both Japanese anime and the term otaku began spreading to Western countries.[11]

It was not until the late 1980s did the word otaku emerge in Chinese popular culture following the rapidly rising trends of computer games and Japanese anime.[11] Although 宅 (zhái) translates to otaku in Chinese, it also encompasses the meaning of “a group of people that have the same hobby” which is often referred to as 御宅族 (yù zhái zú).[12] In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the usage of 宅 (zhái) and its otaku culture became even more popular due to the expansion of the Japanese anime market in China. In fact, during that time, TV Tokyo Corporation teamed up with China’s major Internet video broadcasting site, Tudou, to bring a number of popular anime productions to Chinese viewers, free of charge. Some of the most famous anime featured on the website include Naruto, Bleach, and Gintama. Meanwhile, iQIYI.com, a video broadcasting subsidiary of China’s main portal site Baidu, began selling legitimate anime content.[13]

How did 宅 (zhái) Enter the Chinese Space?

Japanese anime first appeared in China in 1970 through the film "The Dragon Boy" by Hayao Miyazaki.[14] A decade later, Hong Kong aired the series "Astro Boy", which was also broadcasted on mainland China's CCTV in the same year.[14] When otaku culture entered China, its main audiences were children and teenagers who were born after the Reform and Open period (改革开放 găi gé kāi fàng) and embodied a broader receptivity towards popular culture compared to the older generation.[15] Through the import of Japanese manga and anime that aired on CCTV, many Chinese children in the 1980s grew up with anime. Since Astro Boy's huge success, anime series, particularly those that appealed to children such as Doraemon, Ikkyū san, Detective Conan, Crayon Shinchan, and Chibi Maruko-chan, became great hits in China.[16]

By 2004, Japanese “otaku products" (宅向作品 zhái nán zuò pĬn) such as popular Japanese computer games flowed steadily into mainland China through oversea students from Japan and Taiwan.[17] Due to the popularized access to the Internet in the 2010s, various otaku subcultures grew in China and its related products including game consoles, anime figurines, and anime apparels became widespread amongst the younger generations.[17]

Words Associated With 宅 (zhái)

In the early 2010s, the term 宅 (zhái) became known throughout China and those who identified with it were seen as misfits who preferred to stay at home than to cultivate a social life. Therefore, outsiders would often refer to otakus as “fat otaku” (肥宅 féi zhái) due to the preconceived notion that otakus are overweight.[18] In addition, Coca-Cola was given the nickname “the fat otaku's happy drink”(肥宅快乐水 féi zhái kuài lè shuĬ) since the sugary drink is often associated with unhealthy life choices. As otaku culture began spreading beyond the anime and manga circle, “fat otaku” (肥宅 féi zhái) has become a term for youths to mock themselves with in reference to their laziness. Meanwhile, the rather positive expression “fat otaku lifestyle”(肥宅生活 féi zhái shēng huó) simply refers to people that lead a slow paced life and work for joy rather than for profit.[18]

As more people stepped into the otaku circle, more words became associated with otaku. The most common term is "2D otaku" (二次元宅 ėr cì yuán zhái) which is used to define people who are obsessed with anime and manga. Over time, otaku subcultures that go beyond "2D otaku" began to emerge in the Chinese space. Otakus such as: technology otaku (技术宅 jì shù zhái ), computer otaku(电脑宅 diàn năo zhái), gaming otaku(游戏宅 yóu xì zhái), military otaku(军事宅 jūn shì zhái) are very common and is used to define what the person is interested or excel in.[19] In addition, the video platform “BiliBili” (哔哩哔哩 bì lǐ bì lǐ ) is the most popular otaku platform and is a familiar otaku-related term amongst otakus in China. In fact, BiliBili is identified as the largest gathering platform for otakus and is credited to be the Chinese version of Japan's popular anime platform: ニコニコ(niconico). In addition, BiliBili has its humble beginnings as an anime piracy website and during the mid-2010's, the platform deleted its pirated content and joined hands with anime companies to import legalized anime. Since 2018, BiliBil has been involved in the production of several famous Japanese animes.[20]

The Meaning of 宅 (zhái) in Contemporary Chinese Culture

In contemporary Chinese culture, 宅 (zhái) is often used as a noun to address people who are living a semi-reclusive lifestyle with little social interaction and unenthusiastic mental states.[21] Used widely throughout the Chinese Internet space, the term 宅 (zhái) has also become a form of identity for netizens who identify with this lifestyle and consider themselves as a part of otaku subcultures. Within otaku communities online, people are separated into two groups based on their gender: male otakus (宅男 zhái nán) and female otakus (宅女 zhái nǚ). On Baidu Tieba, one of China's most used communication platforms, is a popular discussion board with 3.5 million followers called “Blind Date Bar (相亲吧 xiāngqīn ba)” where otakus share stories about their dating experience. One user called 游戏宅男的春天 (literally: the spring days of the gaming otaku boy, yóuxì zháinán de chūntiān) posted “Ah, it is too difficult to find a like-minded girl now. They all say that I can only play games and that I am not self-motivated.”[22] Not surprisingly, many replies under his post generated common feelings and shared experiences with commenters referring to him as “宅男哥" (otaku brother, zháinán gē)[23] while someone else resonates with him by commenting: “俺也一样” (me too, Ǎn yě yīyàng).[24] In addition, popular press does not simply use 宅 (zhái) as a noun but also as a verb. The article “Life of Otaku” from the magazine Family Fitness Room published in 2008 said: “On weekends, it’s rare to have leisure time since people are obsessed with [being an] otaku at home,” here, the expression: “otaku at home” is referring to 宅在家 (zhái zàijiā) which acts as a verb to express one’s action of staying home.[25]

Misuses and International Appropriations

In the decades after the term, otaku entered China as 宅 (zhái), otakus have created distinct usages and meanings of the word. Overtime, the criticisms of 宅 (zhái) being misused in popular culture outside of the otaku space has also increased. Originally, being called 宅 (zhái) is often regarded as an insult due to its negative connotations of being extremely obsessed with games or anime.[26] Recently however, self-proclaiming oneself as "宅" (zhái) with pride is becoming a public trend.[27] Because of this, criticisms that stem from people with a deep-rooted passion towards the identity of being 宅 (zhái) has become more prominent as they express discontent towards the low standards one needs to fulfill to be considered as an otaku in China.[27]

Meanwhile in the West, otaku is only used to define someone who is obsessed with Japanese anime and manga with this being detrimental to their social skills. In fact, “nerd,” “geek” and "weaboo" are North American terms that are used in similar ways to how 宅 (zhái) is used in China. The term "geek" is used to describe those who are obsessed with subculture and have a lot of knowledge in a certain area. For example, "geek" can be used as: "comic book geek," "anime geek," or "computer geek".[28] "Nerd" is also used to describe people that are "bookworms" or are highly intelligent in a specific area to the point where they barely show any knowledge of the outside world.[28] In addition, people also use “nerdy” and "geeky" to insult one's outer appearance, as untidy hair, glasses, and button down shirts are the stereotype clothing for "nerds" and "geeks." [28] Meanwhile, "weaboo" has a similar meaning to otaku but is used to describe non-Japanese people who present a deep obsession with Japanese culture to the point where they imitate the language, custom, and culture.[28]

Social, Cultural, and Political Problems

Stereotyped as ‘home-stayers,’ Chinese otakus are seen as people who have no social life and are often frowned upon within Chinese culture.[29] In an interview, Gordon, a gamer otaku, is asked if eating instant noodles everyday keeps him full in which he answers with: ”If you don’t move, you won’t be hungry. If you’re not hungry, you don’t need to eat”–– in reference to gaming all day.[30] As implied from the Chinese definition of 宅 (zhái), Gordon is a stereotypical otaku who does not care about his social life or health and exemplifies notorious otaku social problems.

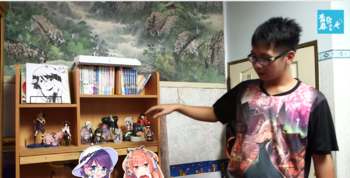

Ding Xinghan, an anime otaku, recounts the backlash he faced as an otaku in an interview: “[One day,] on my way home from buying anime merchandise, some grammas and grandpas looked at me weirdly and commented how anime is very daring and perverted. When I heard that, I felt very self-conscious about myself.”[31] With how often otakus are labelled as ‘fat’ and ‘weird’ people who are interested in violence and pornography, mainstream Chinese culture adopts these negative connotations on otakus and project these views on those who enjoy various otaku subcultures.[32] Hence, in light novels, mangas, and anime that reflect the lives of otakus, otakus are portrayed as those who live a double life: normal at school and around family but indulge in their ‘guilty pleasures’ in their rooms to avoid negative comments and confrontation from those around them.[33]

Otaku subcultures are often politically charged in relation to the hegemonic mainstream culture as demonstrated by how different and ‘weird’ it is in contrast to the mainstream popular culture. In fact, subculture refers to the norms that set the otaku group apart from the mass culture that refers to the norms of the expected.[34] In other words, otaku subcultures are viewed as subpar and ‘different’ because it does not conform to the social-political norms of everyday Chinese culture but represent a ‘new’ culture.[35] An example of hegemonic mass culture is exemplified in Ding’s self-introduction: “You can call us ‘宅宅’ [otakus]. We like to watch anime, read light novels, and play games –– it’s like how you guys like to go on Facebook and Instagram during your free time. We just have interests that differ from yours.”[36] The power of mainstream culture and the negative connotation of otakus is seen here as Ding feels the need to justify his interests by comparing it to mass culture for the everyday audience to relate to his anime subculture obsession.

Studies Related to Otaku

Academically, 宅 (zhái) is referred to as a social phenomenon and subculture style of living that brings negative physical and psychological effects.[37] In 2017, three Chinese scholars from Hebei Agricultural University published “The Influence of Otaku Culture on Contemporary College Students and Feasible Suggestions on Countermeasures,” a journal that encourages the establishment of countermeasures to stop college students from being otakus so they can be a part of society.[38] Furthermore, the Chinese popular press People’s Daily published an article in 2008 titled: “Experts Suggest that Otaku are best to see a Psychologist” reflecting similar views.

According to the western theory of Henry Jerkin's Textual Poachers, audiences, in this case, anime-viewers, are not merely receiving the information, but are also active participants and producers who help create contemporary folk culture while reducing class differences by uniting fans in the 'Utopian community'.[39] Media platforms, like Bilibili, help spread otaku culture amongst the young Chinese generation, and provides space for otakus to actively participate in sharing the same interests and creating their own otaku-related topics. In a discourse study, Zhang, Tian, and Cassany sheds light on a new creative method called “弹幕" (dàn mù) in Bilibili which offers a virtual social network for the younger generation to anonymously communicate with each other about their subculture as their comments appear at the top of the video which then encourages interaction between the users.[40] After Deng Xiaoping's vision of "让一些人先富起来" (ràng yī xiē rén xiān fù qǐ lái), commercialism became rooted and eventually, e-commerce and social media became a container of "…intangible knowledge, desire, affections and emotions," which blurs the boundary between different classes.[40] Therefore, Bilibili, a substantial online platform for anime otakus in China, provides a socializing space and embodies those elements to reduce class difference.

Conclusion

In Chinese culture, otaku comes with negative connotations and is often associated with an antisocial lifestyle that produces unhealthy choices and undesirable stereotypes. Today, the term, 宅 (zhái) continues to be widely used by Chinese youths and on the online world to address those who are hyper-focused on a specific subculture. Despite how negatively otakus are viewed in the Chinese space, games, manga, anime and the Internet continues to be the safe haven for otakus who choose to immerse themselves in the 2D world and disregard what outsiders have to say about them. With the ever-expanding Internet world, Chinese otakus use technology and forums to share a variety of creative thoughts and emotions about their hobbies and subculture-related interests. It is through the collective space otakus have created that Comiday (同人交流会 tóngrén jiāoliú huì), cosplays (角色扮演 jué sè bàn yǎn) and figurine shops 手办店 (shǒu bàn diàn) were born as youths gather together and express their enthusiasm regarding their interests without disapproval from strangers.[41] Chinese otakus impact the world through their unique language and subcultures while blurring the differences of class, gender and nationality despite the eventual possibility of being incorporated into mainstream culture or capital power.[42] Regardless of the oppression and negative stereotypes imposed on otakus over the decades, it has continued to flourish throughout China and remains prominent in the Internet space where the gathering and celebration of the otaku identity continues to prevail.

References

- ↑ rocefactor (2020). "御宅族是怎么来的?只是宅在家不出门那么简单吗?". 凤凰网.

- ↑ Chen, Zhen Troy (2018). "Poetic Prosumption of Animation, Comic, Game and Novel in a Post-Socialist China: A Case of a Popular Video-Sharing Social Media Bilibili as Heterotopia". Journal of Consumer Culture: 1–21.

- ↑ Mao, Zhanwen (2020). "青年亚文化,在"破壁"中展现新图景". 光明日报.

- ↑ Kam, Thiam Huat (2013). “The Common Sense That Makes the ‘Otaku’: Rules for Consuming Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan.” Japan Forum 25 (2): 152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2012.743481.

- ↑ Kam, Thiam Huat (2013). “The Common Sense That Makes the ‘Otaku’: Rules for Consuming Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan.” Japan Forum 25 (2): 152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2012.743481.

- ↑ Kam, Thiam Huat (2013). “The Common Sense That Makes the ‘Otaku’: Rules for Consuming Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan.” Japan Forum 25 (2): 153. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2012.743481.

- ↑ Kinsella, Sharon (1998). “Japanese Subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and the Amateur Manga Movement.” Journal of Japanese Studies 24 (2): 308-311. https://doi.org/10.2307/133236.

- ↑ Kam, Thiam Huat (2013). “The Common Sense That Makes the ‘Otaku’: Rules for Consuming Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan.” Japan Forum 25 (2): 153. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2012.743481.

- ↑ Kam, Thiam Huat (2013). “The Common Sense That Makes the ‘Otaku’: Rules for Consuming Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan.” Japan Forum 25 (2): 153-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2012.743481.

- ↑ Cubbison, Laurie (2005). “Anime Fans, DVDs, and the Authentic Text.” The Velvet Light Trap 56 (1): 45. https://doi.org/10.1353/vlt.2006.0004.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 匿名 (2017). "什么是宅文化 它是怎么诞生的". 第一星座网. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Fu, Yifang (2020). "宅文化的前世今生". 钛媒体: 7.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Syuri (2012). "Anime and Manga Take Root in China". Contemporary Culture Going Global: 2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sencil, Dianne Therese (2015). "More Chinese Teens Turn into 'Otaku'". Yibada English. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ Jin, Jing (2012). "我国宅文化的发展及社会对宅文化的认识". 金媒体. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Syuri (2012). "Anime and Manga Take Root in China". Contemporary Culture Going Global: 1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 点鲸工作室© (2018). "宅文化'编年史". 虎嗅网. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Liang, Min (2019). "青年宅文化现象及反思". 中国报业.

- ↑ Liu, Bing (2019). "宅的种类有多少". 360度全球. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ Wan, Jinlu (2018). "哔哩哔哩分析". 网络财经咨询.

- ↑ Wu, Yaruo (2014). "当代大学生"宅文化"现象的研究和思考". 中国论文榜. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ 宅男的春天 (2020). "哎,现在找个志同道合的妹子太难了。都说我只会打游戏..." 百度相亲吧. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ 宅男的春天 (2020). "哎,现在找个志同道合的妹子太难了。都说我只会打游戏..." 百度相亲吧. 他年无我. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ 宅男的春天 (2020). "哎,现在找个志同道合的妹子太难了。都说我只会打游戏..." 百度相亲吧. Tihmrg; 吱吱吱吱吱. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ Sun, Yan (2008). "On "Zhai Nan" from the Perspective of the Linguistic Theory of Connotation and Denotation". Journal of Hubei University of Education. 25: 2.

- ↑ Newitz, Annalee (1994). "Anime Otaku: Japanese Animation Fans Outside Japan". Bad Subjects (13): 1.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Ji, Jiangfeng (2018). "【文化】中国宅男和日本宅男是不一样的". 搜狐网. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 哥倫布 Columbus (19 August 2019). "「宅男」英文怎么说? Nerd? Geek? Otaku? 一次搞定!". Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ Kirillova, Ksenia, Cheng Peng, and Huiyuan Chen (2019). “Anime Consumer Motivation for Anime Tourism and How to Harness It.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 36 (2): 271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1527274.

- ↑ Yeung, Gordon (2015). “宅男生活大起底.” YouTube video, 0.54-56. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=suran17vEtk&ab_channel=GordonYeung. Accessed 1 November 2020.

- ↑ 青春發言人 (2018). “動漫迷心聲無人知?宅宅有話想說.” YouTube video, 2:19-32. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JB_yE9IXD3M. Accessed 1 November 2020.

- ↑ 青春發言人 (2018). “動漫迷心聲無人知?宅宅有話想說.” YouTube video, 2:36-39. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JB_yE9IXD3M. Accessed 1 November 2020.

- ↑ Lamarre, Thomas (2014). “Cool, Creepy, Moé: Otaku Fictions, Discourses, and Policies.” Diversité urbaine Essai 13 (1): 134. https://doi.org/10.7202/1024714ar.

- ↑ Pastarmadzhieva, Daniela (2012). “Subcultures: From Social to Political.” Trakia Journal of Sciences 10 (4): 81.

- ↑ Pastarmadzhieva, Daniela (2012). “Subcultures: From Social to Political.” Trakia Journal of Sciences 10 (4): 83.

- ↑ 青春發言人 (2018). “動漫迷心聲無人知?宅宅有話想說.” YouTube video, 0:04-18. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JB_yE9IXD3M. Accessed 1 November 2020.

- ↑ Tang, Shenglan (2013). "大学生'宅文化'现象及其对策". 豆丁网.

- ↑ Zhang, Lei; Ren, Yatao; Wang, Tianwei (2017). "宅文化对当代大学生的影响及应对措施的可行性建议". 读书文摘. Retrieved 31 October 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Casey, Brienza (2012). “Taking Otaku Theory Overseas: Comics Studies and Japan’s Theorists of Postmodern Cultural Consumption.” Studies in Comics 3 (2): 213–229. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1386/stic.3.2.213_1.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Zhang, Leticia-Tian, and Daniel Cassany (2020). “Making Sense of Danmu: Coherence in Massive Anonymous Chats on Bilibili.Com.” Discourse Studies 22 (4): 483–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445620940051.

- ↑ 小猪男孩 (2016). "第二届上海SHCC动漫展打造漫迷狂欢日". Mtime时光网.

- ↑ 大猴儿 (2019). ""二次元":青年亚文化的存在及其表达式". 百度资讯.