Course:ANTH302A/2020/Kashmir

Overview

Kashmir is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompasses a larger area that includes the Indian-administered territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, the Pakistani-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, and Chinese-administered territories of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract. [1]

The ownership and status of Kashmir has been a hotly disputed and militarily charged topic between India, China and Pakistan in the 73 years following Partition imposed by British colonial rule.

More recently, on 5 August 2019, the Government of India revoked the special status, or limited autonomy, granted under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution to Jammu and Kashmir. [2] In addition, the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019 was passed by the parliament, enacting the division of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories to be called Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir and Union Territory of Ladakh. The reorganisation took place on 31 October 2019.[3] At the same time, India has implemented militarized clampdown in the Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir[4].

The violent politically-rooted conflicts would only be further heightened by the advent of COVID-19. Lockdown procedures brought on or extended by India in the name of stopping virus spread would only serve to further India's colonization and control over Kashmir. This could be seen in the contradictory strict lockdown policies and flood of non-Kashmiri residents into the area.[5] In the meantime, the traumatic war between India and Pakistan would also be exacerbated by COVID-19.

This page explores the historical inequalities, challenges as well as resilience that Kashmiris embody, from social, economic, caste, mental health, gender and developmental perspectives, amidst the latest pandemic, COVID-19.

The novel coronavirus is new in the world but for the intensity of its consequences and damages it caused to the world’s development, everyone is aware of it and countries on the globe have learned that it would require cooperation and collaboration to triumph together. According to Brown and Blanc, consequences are profound in war-torn countries and in nations with fragile economies because responses to the pandemic will require to break through political violence, low state capacity, increased level of people’s movements, fragmented authority and low trust in leadership[6]. I understand that the collaboration needed would require a strong and stiff relationship, firstly, among neighbouring countries because of movements people make and their interactions with each other would increase the spread if any of them is infected. For countries like India and Pakistan that always fight over Kashmir and whose nationalism ideology among people does not allow for giving up the place, it is hard to believe that a mutual consent to control the spread of pandemic is possible.

It is not possible because Kashmir people do not know the country they belong to and they don’t know what the borders are. In “Kashmir: Why India and Pakistan fight over it” by BBC news, it reports that India claims Kashmir to be fully part of their land and so does Pakistan yet both countries control part of it and are internationally recognized as “Indian-administered Kashmir” and “Pakistan-administered Kashmir.”[7] However, in 2019 the Kashmir became a focus for news in South Asia when the Indian government removed the autonomous status of the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir [8]. It is worthy of note that it is in the same year that the coronavirus pandemic hit the world, starting in China in December 2019 which is how it got the name “COVID-19”

Several papers write that the pandemic in December 2019 outbreak the world right after the announcement by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on August 5th, a day before announcing votes from elections in India, that the article 370 in India’s constitution must be revoked with immediate effects[9]. It is this article that was standing to claim Kashmir's special status that allows these two states to make their own rules and own government since 1954 and its abolishment caused people from there to lose statuses of who they are and where they belong[10]. The same report says that the two Indian special states entered the total lockdown that found public gathering banned, military troops disseminated in the region and telephone networks got cut off to complicate the communication and to make the Kashmiris feel that they don’t belong in that special state anymore [11]. It brought fears among the Kashmiris, including Ms. Mufti who thought that India want Kashmir that is made of Muslims by majority to forcefully join the Hindu religion.

Despite the pandemic, the unrest started right on the day with people coming together to protest against the ruling party’s announcement. Like other protests, it is not easy to keep the 2-meters social distance that the World Health Organization (WHO) always wants people to compel when together. During the protest people want public to hear their voices and they would like this when it is done in a crowd. It happens when people feel each other and understand together the purposes and reasons to why they are protesting. Therefore, it is hard to control if people have obeyed the physical social-distancing rule and in effects, someone tested positive might infect the other who they come in contact. As the results, for the duration of the unrest the number of cases have risen to 15258 cases with 162 COVID-related deaths and it has exposed the shortage of doctors in Kashmir [12]. The shortage of doctors since the date of an announcement in Kashmir is a great scare to the Kashmiris who recorded the first cases of coronavirus in December from 13 people who recently travelled to Iran according to the Al Jazeera's news “‘We'll die like cattle': Kashmiris fear coronavirus outbreak”[13]

The unrest caused the loss of lives for numerous civilians but also as you would imagine, the outbreak also rose to the peak and caused deaths as well. The WHO counts 542 deaths and 28,470 confirmed cases in the Kashmir region today. This is a massive number especially in the region whose population is low, in fact, less than one million. The worst scenario comes when the protesting does not even stop and when the conflicts escalate a day after a day while political leaders break silence on the strategies towards the resolution of an issue.

In addition, Kashmiris do not know their boundaries on borders and therefore, the control of people's movements on borders has always been prone to little success because it would require the two countries to sit together, with fewer accruals and blames towards another, to redraw control lines and for everyone to know where they belong[14]. Otherwise, the uncontrolled movements on borders will always discourage the efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19. For example, the Igihe NewsLetter report that when Rwanda recorded the highest number of COVID-19 cases due to truck transporters from Tanzania, their neighbour in the East, they called for a diplomatic meeting to learn together what the solution should be. Now, the WHO records only eight deaths in Rwanda and a total of 2,453 cases due to working together with neighbouring countries and proper measures to control borders.

COVID-19 And India's Occupation Of Kashmir - Kevin Jiang

After India stripped Kashmir of its autonomy in 2019, tensions rose to unprecedented levels. This has only been heightened by the advent of COVID-19; lockdown procedures brought on by India in the name of stopping viral spread would only serve to further the nation's control over Kashmir.

Introduction

Ever since partition, Kashmir has been a hotly contested territory between India, China, and Pakistan. Tensions only grew hotter in 2019, after the Pulwama suicide bombing attack by Kashmir local and member of the Pakistan-based militant group Jaish-e-Mohammed, Adil Ahmad Dar. Ahmad Dar's attack, coupled with rising anti-India dissent within the region, would prompt drastic action by the leading Hindu-Nationalist party of India.[5] In the coming months, the nation would impose strict lockdowns on the territory aimed at curbing terrorism. This included stripping the region of its statehood in early August, 2019, according to the Associated Press, as well as a government imposed media blackout, during which no foreign journalists would be allowed within the country. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had split Jammu and Kashmir into two federally-controlled territories; in the weeks before the crackdown, a reported 2,300 people would be detained.[15]

India's response to COVID-19

Roughly one year later, a global pandemic would throw the world into crisis. States were shutting down their economies and imposing social lockdowns and new regulations. India was no exception; in what NDTV calls "a human catastrophe," Modi would shutter the nation with a mere four hours of warning time. "The lockdown is in effect a caste atrocity," they wrote, "i.e. a wilful act of violence inflicted on marginalized castes, and invisibilized in the name of halting a virus."[16] In his attempts to halt the spread of novel coronavirus, millions of lower caste and struggling nationals and migrants alike would bear the brunt of his actions. Joblessness and poverty ran rampant among these lower classes, they reported, while the upper castes were relatively unaffected. NDTV argued that India's COVID-19 response functioned to protect the rich while alienating the poor — after all, they wrote, physical distancing is a luxury afforded to the wealthy. But "for the vast majority, it evokes caste humiliations and proscriptions of touch, dining and social relations." Similarly, calls to free activist detainees kept in overcrowded prisons at risk of COVID-19 fell on deaf ears.[16] These injustices and tactics of suppression utilized by Modi within India come into play especially in Kashmir.

Lockdown as a means of control

India's brutal response to COVID-19, as argued by Omer Aijazi in The Conversation, is a tool to further suppress and "accelerate its settler-colonial ambitions in the disputed territory" of Kashmir.[17] Ifat Gazia wrote in The Conversation that the novel coronavirus brought forth harsher limitations on the region, such as a strict curfew.[18] Anyone who violates the curfew, even if they have a pass to do so, "risks being detained by soldiers or police and possibly beaten." Kashmiri journalists, activists, or people who simply broke military order or curfew continue to be arrested and brought to overcrowded prisons where the risk of contagion is high, Gazia continued.[18] Other restrictions on transport, business, and public movement remain in place, reported Global News. "Government forces placed steel barricades and razor wire across many roads, bridges and intersections," they wrote. "Shops and businesses remained shut and police and soldiers stopped residents at checkpoints, only letting an occasional vehicle or pedestrian pass."[19]

History repeated

While the situation in Kashmir might seem novel, India has a history of stoking unrest and cracking down on certain groups in the past. For example, during the 1984 massacre of Sikhs following the assassination of former prime minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards, high ranking government officials were seen during the riots, encouraging on the murder of locals by mobs. NDTV's Truth vs. Hype interviewed several survivors of the genocide, each of whom alleged the involvement of officials in the onslaught.[20] This manipulation of public perception could be seen throughout the past 73 years in Kashmir — as Vox highlighted, the Kashmiri conflict is a violent cycle. After crackdowns by India on Kashmir, locals are radicalized and join with militant groups within Pakistan or protest the Indian government. This in turn leads to further crackdowns, reinforcing India's grip on the region and perpetuating the oppression of Kashmiri people.[5]

Tolls of war

All the while that COVID-19 lockdowns are happening, the Kashmir region is still embroiled in a bitter firefight between India and Pakistan. In fact, according to Gazia, Indian soldiers have killed almost two times more Kashmiris than the virus. Soldiers led to the deaths of 229 people, as of June 30; COVID-19 has only killed 141. What's more, 107 raids of neighbourhoods purported to house rebels since January have left hundreds of locals homeless in the midst of a public health crisis, wrote Gazia.[18] Aijazi adds that India continues to station soldiers in the midst of civilians, making it difficult for Pakistanis to retaliate without harming innocents. "The blurring of civilian and military targets amounts to a war crime," he wrote. The novel coronavirus only makes the situation harder on the locals; not only are they cordoned into tiny bunkers for safety, where the risk of viral transmission is high, locals aren't even allowed to leave their villages in the middle of bombardments due to lockdown travel policies.[17]

The "demographic flooding" of Kashmir

Despite these seemingly strict lockdown protocols, however, tourism for Indian visitors to Kashmir was opened in the height of the pandemic. So too were tens of thousands of Indian nationals allowed to reside in Kashmir since June of 2020, wrote Gazia.[18] This flood of nationals into Kashmir was sparked by a new domicile law passed by India in the midst of COVID-19; under its new tenets, non-Kashmiris will be allowed "to obtain property, compete for government jobs and impact the outcomes of a referendum on Kashmir’s future should it be held," wrote Aijazi. He continued that this "demographic flooding" by India is a colonial strategy employed by India to advance their control over the region.[17] The reopening of tourism in contradictory contrast with the rise of strict lockdown procedures only lends credence to the view that the lockdown was merely a tool for India to further suppress and control the region.

Nation-making, Religion and Racism: Migrant Workers in the Pandemic - Vasilisa Shvedenkova

Religion and race play a key role in shaping the experience of minority groups. This has particular effect in the employment sector in Kashmir, most notably for migrant workers.

Identity in Conflict

South Asia “has had more complex identities than any other region of the world”.[21] Shail Mayaram contends that there is in fact evidence of individual identifying as both Hindu and Muslim. She stresses the importance “‘living together’ both in the past and in our troubled present”.[21] Discussion surrounding contemporary religious identities needs to address: “the consequences of cultural encounter for the histories of castes and communities; the possibility of dual or triple religious affiliation expressed openly or unconsciously; and, dimensions of liminality articulated through varied registers”.[21] In the process of nation-making, violence and peace-making are at the forefront.[22] Veena Das affirms this noting that zones of emergency are marked by “diffused images of an unfinished past, efforts to void the other of all subjectivity, and a world increasingly peopled with a fantasmagoria of shadows”.[23] The memories of Partition permeate the race relations in India controlled Jammu Kashmir. Throughout India, Muslims are lynched for eating beef and labelled as anti-India or pro-Pakistan. These narratives serve the aim of Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Modi, who views Kashmir as a part of India and thus Hindu territory, framing Muslims as an enemy outsider, while effectively branding Hindu Indians as the "standard" citizen of Kashmir.

Migrant Workers

Much of Kashmir’s economy is dependent on migrant labourers. Every year tens of thousands of migrant workers flood into Kashmir looking for work, primarily in masonry, carpentry and agriculture. In many cases, they arrive in early spring and stay about 6 months for the working season; in this time many workers are forced to move around and thus have a large circle of interaction. By the time Covid19 was declared a global pandemic, approximately 40,000 workers had already arrived in the Kashmir valley. Being individuals who have to dislocate from their home, migrant workers are scrutinized as an outsider, when religion and ethnicity come into play violence has played a key role in creating a divide in the Kashmiri communities. Prior to the pandemic militant killings were already prevalent. In the winter of 2019 over 100 migrant workers were moved out of Kashmir after a series of killings.

Significance of Article 370

In South Asia, “nationalist imaginaries have become viciously real in the last decade as the cities of its nation-states are cleaved into a myriad partitions, signifying otherness”.[21] The significance of Prime Minister Modi revoking Article 370 is that it was unexpected by most citizens. There was rumour of Article 35A of the Indian constitution, which gave some special privileges to the people of the state, would be abolished.[24] When Modi stripped Article 370, of which Article 35A was part, Kashmiri people lost much autonomy as identifying as their own nation-state. The Prime Minister argued this move was necessary to put Kashmir on equal footing with the rest of India.[24] The abrogation of this article will have lasting impact in both domestic and migrant workers. The removal of special status of Kashmir gave the government the power to "automatically implement regressive labor codes and other anti-workers measures".[25] In Srinagar, which used to see a heavy migrant influx during the working season, "many house-owners have evicted non-locals".[26] Further, when the Citizenship Amendment Act was passed it offered fast-tracked citizenship for individuals from neighbouring countries yet explicitly barred Muslims from doing so.

This has successfully created “an entire underclass of citizenry, mostly Muslims”.[27] Minority groups and individuals on the verge of economic destitution have become entrapped by the governments hierarchical framework based on location and religion. This religious discrimination has been heavily felt during the Covid19 pandemic. Covid19 has “exposed the complex realities of many labourers who barely survive in a country that is wedded to neoliberal globalization and the hazards of late-stage capitalism. They have been viewed solely as a means of capitalist exploitation and sites of extraction”.[27] With Prime Minister Modi announcing a nation-wide lockdown without warning; Migrant workers in urban centres have been largely displaced with workplaces and all transportation closing overnight, many have been forced to travel long distances home (often by foot) in a desperate move for survival. However, not everyone was able to make even this escape; leaving many, most notably migrants, stranded with no income or way to get home.

Militants and Migrants: October 29 2019 Killings

Militant presence and violence has been a concern for Kashmiri people for many years now. However Modi's repeal of Article 370 has lead to a series of targeted killings of workers from outside the territory. On October 29 militants shot six and killed five workers from West Bengal out of their rented home in Katrasoo village of Kulgam district. The victims were migrant labourers working in the orchards and paddy fields in south Kashmir. According to local security analysts the targeting of non-locals is "directly linked to an emerging wave of identity politics in Kashmir in the aftermath of the Union government".[26]

Demonization and Alienation During Crisis

An important source of the separatist sentiment ignited by Modi has been "the irrational fear of migration and dominance by outsiders".[28]According to Ramasubramanyan, “During times of crises, large factions of India’s population have chosen to scapegoat and demonize the other”.[27] Similar to an epidemic, rumour as Das confirms “is conceived to spread”.[23] Language has the power to transform from communication to being “communicable, infectious, causing things to happen almost as if they had occurred in nature”.[23] This has the power of mounting panic, while naturalizing “the stereotypical distinctions between social groups and hides the social origins and production of hate.”[23] The Islamaphobic tropes of Kashmir’s political landscape are incredibly evident in the handling of information publicly disseminated when the virus was first globally recognized back in March. India’s health ministry repeatedly blamed an Islamic seminary for spreading the coronavirus, following which a widely spread ideology of Muslims causing the virus quickly took over. Further, it has lead to a spark of anti-Muslim violence and Muslim dislocations. According to the local health ministry, ““Certain communities and areas are being labeled [as areas of concentration of the virus,] purely based on false reports”.[29]These are in large part locations with concentrations of migrant workers.

As of August 5 2020, a “total of 25,000 non-Kashmiri migrant workers, out of the 40,000, who had left Jammu and Kashmir after the coronavirus outbreak” have returned to the area for work.[30] According to a spokesperson for the Jammu and Kashmir government they are the only state conducting COVID-19 testing under the real-time polymerase chain reaction. However the unjust systemic discrimination based on being an "outsider" still strongly permeates the everyday lives of the Kashmir migrant workers.

Social Structure and Caste System--Shaydon Dosanjh

The current social structure in Kashmir is based around the caste system. Muslim or Hindu all Kashmiris are subject to social judgement based off their caste. “Historians believe that Muslims have over time consciously adopted the Hindu caste system.” [31]. This adoption by the Muslim society places those in Kashmir despite religion in similar social predicaments. The names of the castes may be different but the social separation between upper middle and lower class persists throughout. “untouchability, a major offshoot of caste, works; with various people allotted different tasks, some cleaner than others. Even a mere physical touch of a gooer who works in a gaan, cleans animal excreta isn’t tolerated because he is deemed impure. This is exactly how valmikis are treated in the Varna system by Brahmins, who believe that even the shadow of lower caste people can bring bad luck to them.” [31]. Although not stated in Indian, Pakistani or Kashmiri law the caste system is social hierarchy that affects the entire population. Those most negatively affected are those in the lower castes, as Hussain previously states a “mere touch” or the “shadow of lower caste people” are considered unlucky and disgusting. The clear discrepancy in value of human life present in countries with the caste system has been magnified throughout the last six months. The corona virus pandemic has shown a bright light on the inequality of social structures like the one present in Kashmir.

As Kashmir’s caste system is based off the Hindu social structure that originated in India we can compare and analyze the effects that the Corona Virus pandemic has had in India to Kashmir. “Nowhere in the world has a lockdown been as inhuman or imposed with such contempt for the lives of its millions of working poor. The Modi government's turning of a health challenge into a human catastrophe and the approval of a large section of India's elites can only be explained by casteism, which grades people on a hereditary hierarchy of worth, and legitimizes the brutalization of 'lesser beings” [16]. The Modi inflicted lockdown in India has been described as a caste crisis. The lockdown which impacted both India and Kashmir were inflicted without any regard for the lower castes. “Even the term 'social distancing,' to which elites have taken like fish to water, is characteristically tone deaf: for the vast majority, it evokes caste humiliations and proscriptions of touch, dining and social relations.” [16]. In India like Kashmir the lower castes don’t have the luxury to social distance, the lucky ones live in small homes with large families, many live in poverty. Modi has asked those who are homeless living meal to meal to social distance and stay at home. “The lockdown is in effect a caste atrocity i.e. a wilful act of violence inflicted on marginalized castes, and invisibilized in the name of halting a virus. [16]. This lockdown has placed countless lives at risk. Without government support or means to earn money many Kashmiris and Indians alike have and will go hungry. Although the lower castes of both India and Kashmir have had similar consequences of the pandemic, there is a larger burden to bear for the Kashmiris.

Due to the geo-political state Kashmir has been in for several centuries, the Pandemic has merely magnified existing issues. Any existing social hierarchy in Kashmir is trumped by Indian officials. “The laws for acquiring land and permanent residency were altered amidst the pandemic, making it easier for Indians to settle within the region. Soon after the announcement of these changes, Kashmiris were warned against any criticism of the new laws by the local police. They are expected to be grateful for the incoming invasion of potential Indian settlers, who outnumber each one of them by more than a hundred.” [32]. India used the climate of the current pandemic to reset social structure in Kashmir. For hundreds of years Kashmiri’s have had their own issues regarding social structure and land ownership, but now their issues go past dealing with one an another and include incoming foreigners. Despite caste, or land ownership all Kashmiris are at risk of incoming Indian military. “These changes also incentivize the systematic abuses carried out by Indian military, handing the members a promise of ‘holy Hindu land’ in exchange for keeping the indigenous protest in check by any means necessary.”[32] This order by the Indian government places all Kashmiri residents who oppose the overtaking of their land at the discretion of the Indian military. This resets any social hierarchy existent within Kashmir and places all below incoming foreigners.

“I realized my caste is something that would differentiate me from others in ways I wouldn’t like; that based on my caste my level of intelligence will be decided, and my caste will determine my basic human rights. With time, I realized I wasn’t alone.[33] For centuries caste has determined the outcomes of countless lives throughout Kashmir. It’s core stems from a marriage aspect. Not wanting to marry your children to anyone beneath their station. Since then it has grown into a deeply cultural prejudice that impacts one’s education, income, friends, family, rights, and majority of the aspects of your life. Over the past six months throughout the pandemic many Kashmiris in lower castes have suffered with the economic lockdown and lack of any financial support. Due to the geo-political climate of Kashmir, unlike many other south Asian countries even those in the highest castes have suffered extremely due to the militarization and foreign immigration into Kashmir.

Mental Health and Caste in Kashmir--Noor Anwar

Mental Wellness in the Global South

The deep-rooted history of the oppressive caste system in India has introduced a slew of peripheral issues, mental health being one among many. Before a connection is made between mental health and Kashmir, or between mental health and caste, the system of caste has to be understood on its own. Professor Rai discusses the fundamentals of caste and caste violence in her interview with Yale, citing that caste had always existed in the localities of India, it was only legitimized by the British rule, thus solidifying it into a system. In this Interview, Rai states the ideological concept of ‘caste warfare’, something that will aid in highlighting the intersections of caste, the ongoing mental health crisis, and Kashmir.[34]

The ‘warfare’ that Rai refers to are actual clans of army within her locality of research in Bihar. Similarly, a video made by Vox titled How this border transformed a subcontinent describes partition as a "violent separation", the same violent lens can be applied to the separation of castes, rather than nations.[35] In the sense of caste in broader India, taunts and micro-aggressions are a microcosm of casteist warfare. These microcosms reflect in the suicides of doctors, students, and professionals who deal with harassment from upper caste colleagues and peers. Divya Kandukuri has worked with individuals affected by this firsthand. She is the founder of Blue Dawn, a mental health support and facilitation group that focuses on caste and intergenerational trauma.[36] The need for this mental health support group was raised when Kandukuri experienced casteism herself. Her mental health suffered, and she noticed the lack of caste-specific mental health initiatives. Thus, the intersection of depreciating mental health, and the caste-based system are inextricably linked through the microcosmic warfare experienced by low-caste Indians everyday. Seale-Feldman and Upadhaya raise a similar question in their article Mental Health after the Earthquake: Building Nepal’s Mental Health System in Times of Emergency. They raise concerns about the intricacies of a locality that have been hit by disaster, questioning “How will it be ensured that counselors and community health workers are able to appropriately help the diverse communities that have been scarred by unspeakable loss?”.[37] The diversity of a community speaks for its traumas. The need for context-specific trauma counsellors seem to be at need throughout the Global South.

'Caste Warefare' and Mental Illness in Kashmir

In relation to Kashmir, it is currently suffering through two forms of warfare. The first being the aforementioned caste warfare, and secondly, the quite literal military occupation of Kashmir. This was reflected in a study done by Bio Med Central (BMC). A group of researchers asked local Kashmiris a series of questions in regards to their mental health. Their depreciating mental health relied on two things; socio-cultural experiences, and specific traumatic experiences of the military occupation of Kashmir. Though Kashmir is a majority-Muslim locality, as Islam is a religion that rejects casteism and tribes, its community has developed a social structure based on one, nonetheless. Arsilan, a Kashmiri blogger, cites that the “social system in Kashmir [is] … delightfully plastic”.[38] Though Kashmir does not have an overtly embedded caste system, the inherent implications of ethnic identity are reflected in a caste-like system. These can be illustrated through the existence and sustenance of upper-castes like Syeds and lower-castes like Gooers. They are practiced through dowry systems, marriage proposals, and the importance and reliance on employment. These social imaginations are all held by the notion of caste. In BMC's study, the aforementioned were also all referred to by Kashmiri locals as a cause for the downward spiral of their mental health. In regards to socio-economic factors, poverty was realized as a major role in mental illness. When interviewed, one patron said that “People who are poor and cannot afford [treatment], leave such persons [persons with mental health problems] on their own, thinking that they will get better by themselves, or else we see, many people don’t even seek treatment [for such persons]”. Poverty is linked to class. Upper-caste Brahmins and Syeds are recipients of gate-kept opportunities not afforded to lower-caste Gooers or Dalits. This disparity in opportunity and accessibility realizes itself through the very real implications of class and mental health. Poor people cannot afford mental health facilities nor treatment. The lack of education about such endeavours may not have been made clear nor accessible to the lower-caste groups of Kashmir. Thus, the ramifications of these intersections have exacerbated the mental illnesses of the lower-caste Kashmiris and have left them destitute of any support.

As mentioned previously, BMC’s research also suggested that specific traumatic events of occupation were a strong factor in mental illness in Kashmiris. Lead researches Housen states that “frequent confrontations with violence … including displacement, exposure to crossfire, ballistic trauma, round-up raids, torture, rape, forced labour, arrests/kidnappings and disappearances” occurred in Kashmir. [39] This echoes Rai’s previous concept of ‘warfare’ in a physical, tangible sense rather than the aforementioned metaphorical sense. Now, with the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, schools have shut down and lockdowns in place, one would describe this as a third kind of warfare. The coupling of these three 'warfares', literal, biological, and emotional, echo Seal-Feldman and Upadhaya's previous concern about the intricacies of varied oppression.

The Future of Mental Wellness in Kashmir

Lack of accessibility and education in mental health, being privy to socio-economic, and cultural standards, military occupation, as well as the current on-going pandemic have exacerbated the desperate need for mental wellness in Kashmir. Though reports and statistics are still quite rare in regards to caste-specific effects on mental illness, especially within the global pandemic, the effects of mental illness through trauma have always existed. To highlight the role that systems of oppression play within the intersections of wellness is a first step to intercede the damage that these systems have played within displaced, and oppressed communities in not only Kashmir, but the Global South.

Gender Inequality Under COVID-19 Pandemic in Kashmir -- Congrui Gu

The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the pre-existing inequalities, and gender inequality is one of them[40]. With the territorial and sovereignty disputes in Kashmir, the phenomena of gender inequality, such as gender violence, are not uncommon. Women have often been the targets and survivors of violence suffering from many aspects.[41] However, the epidemic has complicated gender inequality and its consequences in this region.

Domestic Violence and Lack of Social Protection

In Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, militarization has intensified gender vulnerability. Women have suffered from various forms of violence for years.[41] During COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence has become a serious problem. The outbreak of COVID-19 continues the lockdown in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir that began in August 2019. Under this situation, women have trapped with domestic violence perpetrators.[41] The article “How COVID-19 Worsens Gender Inequality in Nepal” explains that the traditional concept of male superiority, constraint of mobility, fear of the epidemic, unemployment and loss of income together constitute the reasons for the increase in domestic violence[42]. In the face of increasing domestic violence, social protection is lacking. Channels for women to seek social help are reduced. The Jammu and Kashmir State Women Commission has already suspended its activity since last year because of the militarized lockdown. [43] In addition, women would vent their emotions to their colleagues or friends before; but now this channel is disappearing due to coronavirus. Due to the cultural norms, women are not valued in their families, so they are even hard to get help from parents.[43] Simultaneously, domestic violence has been overshadowed by harder matter, the pandemic. Many institutions fight with COVID-19 so there is no place for women to ask for help. For example, because of the shortage of medical resources and the high possibility of infection in the hospital, it is very difficult for women to get treatment after being beaten[43].

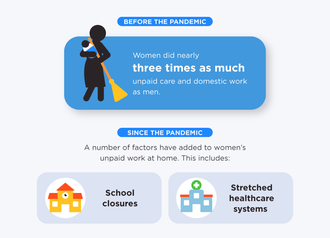

Increased Care Work and Risk of Infection

Kashmiri women suffer from the traditional gender norms that attribute care roles to women in the domestic sphere. The pandemic has caused school closure, the overwhelmed healthcare system, and the increasing need for elderly care. Therefore, the burden of household and care work of women increase.[40] In joint families, women’s workload doubled during the lockdown, because the family pressure forces them to abide by the gender norms at home[44]. Also, the care of patients is usually done by women. Due to the lower social status of women, the society does not pay much attention to their health condition and protection. Thus, the possibility for women to be infected with COVID-19 is increased. In addition to the possibility of infection through nursing work, women have other concerns. Females have unique health needs, but they are less likely to have access to quality health services, essential medicines and vaccines, maternal and reproductive health care. Worryingly, many pregnant women are being infected. At the beginning of June, there were over one hundred women infected by coronavirus.[40] Some measures have been taken by administration; however, the hospitals focus more on fighting with the epidemic, health resources are used by infected patients. Closure of health care units and private clinics also cannot provide enough health care for pregnant women. The lack of health services damages the health of pregnant women and even leads those women to death.[40]

Destitute Women

This pandemic has created many new challenges for poor, marginalized women and their families. The coronavirus lockdown makes destitute women in Kashmir more scared even than they were under a clampdown for more than half year. Nighat Shafi Pandit, ,chairman of the Help Foundation, said that she was not afraid of bombs or bullets because these things would only hurt her. But if she goes out during pandemic, it is a risk not only for her family, but also for the people she meets.[45] These concerns stop women from going out. For families that rely on the income of women doing small businesses such as textile goods to support their families, they lose their income altogether because. These women and their families are plagued by the hunger and lack of health protection because they cannot afford.[45] Help foundation and other institutions have also been hit by the pandemic. The epidemic prevents people from communicating with each other, thus a lot of work to help destitute women cannot be carried out. Lack of funding is also a problem for institutions that help destitute women. The local people used to donate money and came to help voluntarily. But when businesses close and people lose their jobs, the help stops. In addition, commissions and NGOs help register destitute women in Kashmir to survive but they can't generate money either.[45]

Solutions and Dilemma

According to Omer Aijazi, disaster like COVID-19 pandemic, is not a flat topic to victims and survivors. Disasters are lived, experienced, and embodied in multiple ways.[46] The influence brought by disasters is complicated. Disaster and victims or survivors interact each other. They are not isolated, but influence each other. Gender inequality in Kashmir has been intensified by pandemic. Simultaneously, some problems brought by gender inequality have aggravated the spread of virus. Consequently, during the pandemic, women's suffering has doubled and even endanger their health and lives. Thus, simple economic and health aid are not enough. Policies, laws and supporting organizations should defend women’s rights. Improving Kashmiri women’s living standards, increasing their political and public participation, and provide more psycho-social support services are required[47]. These will have positive impacts on preventing the spread of COVID-19 and social development after the pandemic. However, it should be careful when trying to eliminate gender inequality and its problems in Kashmir. In Nightmarch, Alpa Shah describes that though Maoists try to vanish patriarchal values and desire systematic change on gender norms, they reproduce the gender norms which they are trying to attack[48].

However, the implementation of these solutions faces a dilemma. Kashmir now faces more serious matters, such as sovereignty and pandemic. The issue of gender inequality is overshadowed. Although Kashmiri women played important social roles and actively participated in political protests for decades; sustained, non-political and women centered activism has been greatly lacking[41]. Women's counterattack against gender inequality has not been found during pandemic as well. In addition to the cultural influence, other factors also affect women in Kashmir to fight for equality and rights. For example, in Indian-administered Kashmir, militarization makes women' more vulnerable and their situation more dangerous[4]. And during the outbreak, vulnerable health care systems and increasingly infected people have already taken over the public view.

Resistance and re-imagination of Kashmir development --Serena (Zhaohe) Zhang

This section will explore the resistant spirits of Kashmiris from a regional perspective, and an image of Kashmiris different from the usual depiction of them as survivors or victims of political oppressions and the pandemic. Just as Aijazi pointed out, sometimes the highlighting of trauma and calculations might unknowingly contribute to the dehumanization of victims of disasters, and the survivors’ lived experiences are often undermined. [46] Through focusing on local responses to the pandemic, I hope to show an empowering image of Kashmiris.

The resistance narrative of local people (religious communities, food culture)

The politics of emancipation--Azadi in Kashmiri language (the word ‘azadi’, of Persian origin, means ‘freedom’ and has almost become a synonym in Kashmir for the movement for self-determination), is representative of the historical resistance of Kashmir people against oppressions from both India and Pakistan.[49] India has been using settler colonial strategies such as mass-surveillance against the “rebellious” Kashmiri emancipation supporters to dilute Kashmiris’ solidarity and oppress their free expressions of opinions, infringing upon the basic human rights of Azadi advocates. India has already tried to alter the laws for acquiring land and permanent residency amidst the pandemic, to advance its settlement agenda and foster a systematically abusive military in Kashmir. As mentioned from previous sections of India’s military intervention in Kashmir, Kashmiri identity has been split--”In Kashmir, the Indian state translates 'us' into supporters of their army/occupation forces, and 'them' to Kashmiri Muslims.” [50]But Kashmir people continued their resistance despite hardships.

Across religious communities, Muslims and Sikhs living in the Kashmir region have been forming solidarity with each other despite India’s persecutions. During the pandemic, some local Muslims performed last rites for a Sikh who passed away in Ganderbal district of Jammu and Kashmir. The local people informed police and officials of Sikh’s ritual and used their own money to arrange his cremation and help his wife. "It is our duty to help neighbours irrespective of their religion," Abdul Rehman, a local resident, said.[51] By building cross-community solidarities, both Muslims and Sikhs find, as sociologist Shruti Devgan writes, legitimacy for their own suffering in the experiences of the other. Not only is there mutual respect for the ‘other’ but there is the explicit recognition and practice of religious pluralism on the ground. [52]Kashmiris have shown extraordinary ability of inclusion for diverse communities living in and migrating to the region.

On another hand, The solidarity during and post the pandemic of Kashmiris can be found in the kitchen, where people would go out of their way to prepare sophisticated food to bond with their neighbours or guests. Food is a form of Kashmiris’ historical continuity, and is a symbol of neighbourhood closeness, family heritage and a sense of attachment to the land. The kitchen and food environment is also an “informal” arena for dialogues and public opinion expressions, especially when nation-state remains an unjust and unreliable adjudicator of Kashmiri life. On a more fundamental level, India’s settler colonial tactics are oriented towards separation and disconnectedness, isolating the self from others, so the solidarity and resistance of Kashmiri people would mean to insist otherwise, to celebrate community spirits and radical hospitality. Kashmiris’ strengths, commitments, loyalties and imaginations must be emphasized, and they must create their own ethics of care and measures of success that are different from those emphasizing on complicity, silence and inaction. [53]

Reparations and Allyship centered around Kashmiris (Problems of competitive humanitarianism and merits of local NGOs)

Reparations for the Kashmir people must be centered on local people’s needs and experiences, international aids and regional developments during and after the pandemic especially. It is noteworthy the problems of competitive humanitarianism can sometimes be less efficient in helping with disaster relief causes. As Stirrat mentioned, sometimes international aids to disaster impacted regions have high levels of competition and lack of coordination among agencies, and it is mostly because these aiding institutions are not as sensitive to the local population, their different needs and how to better meet them. Competitive NGOs and international interventions require fast effectiveness of the money spent, pressures from stakeholders to appear to be “effective” in media coverages can distract aid workers from doing substantial philanthropies, reinforcing the inequalities already existing in local societies. [54] Thus, Aijazi warned us, real allyship is not just about donating money or resources to appear better in front of the camera, allyship is about listening, unlearning and accepting discomfort. Allies need to listen deeply and centre the voices of Kashmiris, where their experiences will be the measurements for the success of disaster relief. [53]

Within Kashmir, local Kashmiri businesses and NGOs have shown their community spirit by empowering local workers to produce the medical resources needed during the pandemic. ELFA--an NGO based in Srinagar for example, tried to employ local tailors including women to make the masks needed, and obtained lots of hand sanitizers from local medical agencies. It has also worked hand in hand with government agencies and authorities to advance philanthropic work to help those most in need. As ELFA noted, even the pandemic affected both the rich and the poor, some are more severely impacted that they can not even afford basic ration or food supplies. ELFA and other NGOs' work of helping these people symbolizes the Kashmiri spirit of unity and solidarity.[55] Not only them, other monetary contributions from local business owners and samaritans have started pouring in Jammu and Kashmir, free masks and hand sanitizers are distributed to the poor, even ordinary people would give small amounts of money or resources (such as their cars or ambulances) to the administration to fight the COVID-19. These local initiatives and NGO work have received appreciations from government officials, and on some level formed closer relationships between the Kashmir government and their people.[56] These locally initiated aids can help with the local employments, tailor to the needs and contextual sensitivity of locals, and have good coordinations with government agencies.

A Regionally Sensitive Approach in The Post-revocation Era

Since the revocation of Jammu and Kashmir's special status in 2019, the majority Muslim populations from the Jammu and Kashmir region are critical of Modi's decisions, accusing it to be insensitive to local public opinions and containing human rights violations, whereas in Ladakh the majority of residents are Buddhists, and some quite support Modi's decision, saying they do not have many cultural similarities with Jammu and Kashmir, and the separation of them will help with the running of their businesses. [57] Regardless, local residents from both regions are concerned about how the government will approach their developments, without breaking local environments and customs.

To understand India's radical approach of interfering Kashmir contextually, it is similar to the British imperial rule--militarized occupation, muzzling free speech, and cultural homogenization, except by a native ruling government, the goal is to absorb a region of 13 million people that long resisted integration with the rest of the Indian politic.[58] Just as Martin reminds us from his ethnographic study of the region of Gilgit located in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and previously British ruled, colonialism does not just end with the independence of a nation or region, but continues to exist within the nation as long as the power dynamics of oppressions still exist, and might continue to endanger anti-colonial struggles. [59] To overcome post-colonial challenges requires deeper investigations and cares to regional specific populations.

Kashmir’s post-pandemic new normal

It has been a year since Kashmir was stripped of their special status, and the abnormal status of the region has been framed as normalcy by Indian state media, and the international community has turned a blind eye to it. Will the pandemic bring any difference to the region? The pandemic has changed or facilitated changes in almost every aspect of life for Kashmiris as much as the rest of the world, from gender, class and religious dynamics to remote working, the suspension of lots of offline businesses and manufacturing and other aspects of the economy. For example, lockdown in Kashmir has pushed most people to stay longer at home, which means potentially more family bonding and individual religious practices time are available.

Just as Sharma suggested, we should not look at the changes in Kashmir and Kashmiris’ efforts only using the trauma model, as if Kashmiris are all victims of suffering or oppression, but we can shed more lights on the resilience and continuous hard work that local communities have put in their Azadi cause on an everyday basis, these efforts are always ongoing.[60] Kashmiri people would continue to refuse the oppression policies of any kind, they will not accept the imposed oppression on them as the normal but will continue to fight for their identity and emancipation, their rights and dignity. As Aijazi pointed out, the Line of Control does not signal the dismal closure of Kashmir’s futures or potentials, the hopeful future is still yet to come, it will be a future where Kashmiris’ can freely live, learn and laugh. [17]

Conclusion

Although Kashmir faces severe challenges both domestically and from foreign affairs, only through understanding the structural issues of: inequality, historical conflict, religion, caste, and gender, and mental wellness we can we better understand the plight of Kashmiris under an occupied state. Despite the COVID-19 breaking the normality of life for Kashmiris, new opportunities and perspectives will and have emerged through community development, international aid, and grassroots organizations. The understanding of the decades of various intricacies of oppression bestowed upon Kashmir and its patrons is embedded into its justice.

References

- ↑ "Kashmir". Wikipedia. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ↑ Rais, Akhtar. "Jammu and Kashmir". Britannica.

- ↑ "Article 370 of the Constitution of India".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mushtaq, Samreen (19 September 2019). "Militarisation, misogyny and gendered violence in Kashmir". Engenderings. The London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Vox (2019). "The conflict in Kashmir, explained". YouTube. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ↑ Brown, Frances; Blanc, Jarrett (14 April 2020). "Coronavirus in Conflict Zones: A Sobering Landscape". The Cornegie Endowment for International Peaace.

- ↑ Biswas, Soutik (8 August 2019). "Kashmir: Why India and Pakistan fight over it". The BBC.

- ↑ Staniland, Paul (14 April 2020). "Kashmir, India, and Pakistan and Coronavirus". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ↑ Srivastava, Spriha (5 August 2019). "India revokes special status for Kashmir. Here's what it means". CNBC.

- ↑ Lunn, John (8 August 2019). "Kashmir: The effects of revoking Article 370". House of Commons Library.

- ↑ Fareed, Rifat; Krishnan, Murali (4 August 2020). "Kashmir: A year of lockdown and lost autonomy". DW-Made for Minds.

- ↑ Hussain, Ashiq (22 July 2020). "Jammu and Kashmir crosses 15,000-mark in 145 days with 608 new Covid-19 cases". HindustanTimes.

- ↑ Regencia, Ted (23 March 2020). "'We'll die like cattle': Kashmiris fear coronavirus outbreak". The Al Jazeera.

- ↑ Bensinger, Greg (14 February 2020). "Google redraws the borders on maps depending on who's looking". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Hussain, Aijaz (August 21, 2019). "At least 2,300 detained in crackdown in Indian-administered Kashmir". The Associated Press.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Choudhury, Chitrangada (May 27, 2020). "India's Pandemic Response Is A Caste Atrocity". NDTV.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Aijazi, Omer (7 May 2020). "India uses coronavirus pandemic to exploit human rights in Kashmir". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Gazia, Ifat (July 20, 2020). "In Kashmir, military lockdown and pandemic combined are one giant deadly threat". The Conversation.

- ↑ Hussain, Aijaz (August 5, 2020). "Coronavirus security restrictions enforced in Kashmir 1 year after autonomy was stripped". Global News.

- ↑ "Truth vs Hype: '84 Riots - Political complicity, aborted justice". NDTV. Feb 8, 2014.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Mayaram, Shail. "Beyond Ethnicity: Being Hindu and Muslim in South Asia". Lived Islam in South Asia. 1: 18–39 – via Taylor & Francis Group.

- ↑ Mines & Lamb (2010). "Introduction to Part Five "Nation-Making"". Everyday Life in South Asia-Second Edition (ELSA): 309–325.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Das, Veena. "Official Narratives, Rumour, And the Social Production of Hate". Social Identities 4: 109–130.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Article 370: What happened with Kashmir and why it matters". BBC. 5 August 2019.

- ↑ Kumar, Arun (14 August 2019). "Domestic and migrant workers hit hard by abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir". People's Dispatch.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Mohammad, Moazum. "Why militants are killing migrant workers in Kashmir". India Today.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Ramasubramanyam, Jay. "India's treatment of Muslims and migrants puts lives at risk during COVID-19". The Conversation.

- ↑ Kumar, Abhinav. "Kashmir's future is tied to India's, it is for all of us to decide what that will be". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ Gettleman, Jeffrey. "In India, Coronavirus Fans Religious Hatred". The New York Times.

- ↑ "25,000 non-Kashmiri migrant workers return to J-K". The New Indian Express. 5 August 2020.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hussain, Aqib (26 April 2020). "Caste Discrimination in Kashmir: Few Personal Observations". Wande. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Misgar, Umar Lateef (10 June 2020). "Amidst occupation and pandemic, Kashmir gasps for breath". Pen/OPP. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ↑ Hussain, Aijaz (5 August 2020). "Coronavirus security restrictions enforced in Kashmir 1 year after autonomy was stripped". Global News. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ↑ Rai, Mridu. "Prof. Mridu Rai: Caste system in India". Macmillan Report.

- ↑ Vox. "How this border transformed a subcontinent | India & Pakistan".

- ↑ Muzaffar, Maroosha. "When Mental Health Collides With Caste Identity". The Wire.

- ↑ Seale-Feldman, Aidan; Upadhaya, Nawaraj (October 2015). "Mental Health after the Earthquake: Building Nepal's Mental Health System in Times of Emergency".

- ↑ Aziz, Arsilan (March 2018). "The Case Against Caste Discrimination Among Kashmiri Muslims".

- ↑ Housen, Tambri (December 2019). "Dua Ti Dawa Ti: understanding psychological distress in the ten districts of the Kashmir Valley and community mental health service needs". BMC Conflict and Health.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Qureshi, Sadiqa Shafiq (10 August 2020). "Impact of Covid-19: A gender perspective". Greater Kashmir. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) (July 2011). "Half Widow, Half Wife? Responding to Gendered Violence in Kashmir" (PDF). Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ Luna, K.C. (23 June 2020). "How COVID-19 Worsens Gender Inequality in Nepal". The Diplomat. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Nabi, Safina (9 July 2020). "Nowhere to turn for women facing violence in Kashmir". The New Humanitarian. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ Yousuf, Ambreen (31 May 2020). "How are Women fighting the "Shadow Pandemic"?". Kashmir Images. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Nabi, Safina (13 April 2020). "Coronavirus Outbreak: Destitute women of Kashmir bear the greatest brunt of COVID-19 lockdown". Firstpost. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Aijazi, Omer (2016). "Who Is Chandni bibi?: Survival as Embodiment in Disaster Disrupted Northern Pakistan". WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly. The Feminist Press at the City University of New York. 44(1),: 95-110. doi:10.17613/m6cz32499 – via Project MUSE.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- ↑ Haji, Altaf Hussain (29 June 2020). "Situation of gender equality and impact of COVID-19 pandemic". Rising Kashmir. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ↑ Shah, Alpa (2018). Nightmarch. Proquest Ebook Central. ISBN 9780226590332.

- ↑ Sharma, S. (9 January 2020). "Labouring for Kashmir's azadi: Ongoing violence and resistance in Maisuma, Srinagar". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 54(1): 27–50 – via SAGE journals.

- ↑ Chak, Farhan Mujahid (20 August 2019). "Kashmir, genocide and the spirit of resistance". TheNewArab.

- ↑ "Muslims perform last rites of Sikh in J&K's Ganderbal amid lockdown". The Tribuune-voice of the people. 17 May 2020.

- ↑ Malhotra, Khushdeep Kaur (23 January 2020). "Shared Trauma Underpins Sikh-Muslim Solidarity in Kashmir". THE WIRE.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Aijazi, Omer (18 August 2019). "How to be an ally with Kashmir: War stories from the kitchen". THE CONVERSATION.

- ↑ Sirrat, Jock (Summer 2020). "Competitive Humanitarianism: Relief and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka". Anthropology Today. 22: 11–16.

- ↑ Reethu Ravi (1 April 2020). "Coronavirus Lockdown: This Kashmir NGO Has Distributed Nearly 15,000 Emergency Supplies". The Logical Indian.

- ↑ Idrees Bukhtiyar (29 March 2020). "Donations pour in for COVID-19 relief in J&K". hindustantimes.

- ↑ rfi. "印度总理许诺将更好地发展查谟和克什米尔经济". rfi.

- ↑ AMAR, DIWAKAR. "What do Kashmir and Hong Kong have in common? The British Empire". TRT WORLD.

- ↑ Sokefeld, Martin (2005). "From Colonialism to Postcolonial Colonialism: Changing Modes of Domination in the Northern Areas of Pakistan". The Journal of Asian Studies. 64(4): 939–973.

- ↑ Sharma, S (Jan 2020). "Labouring for Kashmir's azadi: Ongoing violence and resistance in Maisuma, Srinagar". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 54(1): 27–50 – via SAGE Journal.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community. |