Course:ANTH213/2024/topic/Migration & Citizenship - Alexandra, Renzi, Nara, Maya, Carmanah

Introduction

Migration, in its simplest definition, is the movement of people from one place to another. It is a simple phenomenon that has gained great attention nowadays because of its shifting and growing nature in the world scenario. People may think of migration as a recent phenomenon, however, it has been a fundamental aspect of human history.

Humans have always migrated in groups and as individuals for several different reasons. Natural disasters and climate change are environmental factors that lead to the displacement of people. War and conflict are socio-political factors pushing individuals to leave their place of origin. Facing oppression because of one’s ethnicity, religion, gender, race, and culture can lead to human rights violations, and government persecution which increases the odds of an individual seeking asylum elsewhere. Things such as labor standards, poverty, and the overall state of a country to provide a good quality of life can also be factors.

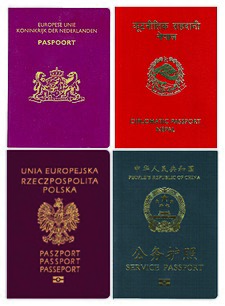

Now when talking about migration another important topic that often surges is citizenship, but what does it mean to be a citizen of a country? In its strictest sense, citizenship is a legal status that means a person has a right to live in a state and that state cannot refuse them entry or deport them. This legal status may be conferred at birth, or, in some states, obtained through naturalization. But in many cases, the dimension of citizenship is a much more symbolic one. The complex and often assumed relationship between citizenship and belonging to a nation goes way deeper than just the legal system. Yes, citizenship makes a person eligible to make use of the public assets the government provides, but it's also about integration into society.

Immigration policies establish bureaucratic classifications for individuals, determining who is permitted to enter and live in destination countries and who is denied access to crossing borders or attaining legal status. These policies also dictate the disparate rights granted to residents based on these classifications. The selection and stratification inherent in these policies, even when presented as ostensibly rooted in considerations of skills are actually heavily influenced by notions of national identity, gender, sexuality, class, race, and postcolonial dynamics.

Gender Dynamics

Gender is a very complex and diverse topic. It refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviors, expressions, and identities that societies place on individuals based on their perceived sex. Although sex refers to the biological characteristics one may hold either in the male, female, or intersex categories, Gender encompasses a broader spectrum. Amongst the exploration of Gender, there is a strong connection between Migration and gaining the right to own citizenship, as these three are interconnected and significantly impact the experiences of migrants worldwide. Such can even include the conversation regarding the medicalization of Gender. This would consist of Intersex individuals who may face barriers in accessing legal recognition of their gender identity, obtaining medical care, and participating in society due to discrimination and legal protection. Families may also face pressure when trying to conform to societal expectations and, therefore, may seek medical help to represent the status quo within their new cultural context during their migration process (Kessler). There are also many other harsh gender-focused realities concerning the migration process. This, for instance, can be prevalent in the number of women who try to resettle for better opportunities for domestic work. Men often migrate to get higher-paying jobs (Kofman and Raghuram). These gendered patterns, in turn, influence one's access to hold onto their rights and sense of belonging. It usually occurs, as mentioned, due to stereotypes and discrimination. When a woman works a low-paying job, such sectors often come with limited job security and minimal access to benefits, including healthcare. These issues are deeply influenced by intersecting aspects, including race, class, and sexuality, changing the shape of opportunities and challenges (Anthias).

Gendered Realities of Migration:

Knowing that the process of Migration is inherently gendered, there are many expectations within the lens of gender roles. As briefly mentioned, women, men, and Gender non-conforming individuals may migrate for various reasons, including promising economic opportunities to better themselves and their families' overall quality of life. For family reunions, people may relocate to come back together after significant events, including issues like wars, and thirdly, gender-based violence. These examples are seemingly interconnected, and one can be a prevalent cause of the other. The examination of Enakshi Dua discussed how the Canadian authorities encouraged and restricted the Migration of women from Asia. This was done because people followed through with the interests of the dominant white settler society and, therefore, manipulated differences between cultures (Dua). Anthias (2013) drew upon the Intersectionality of Gender with different social identities, which is crucial to understanding different diverse experiences. This intersectional approach shows how various types of Gender and privilege intersect to shape access to rights and opportunities for social inclusion (Anthias). Many kinds of discrimination can go beyond Gender and into intersecting identities. There are also privilege and power dynamics. Intersectionality demonstrates how intersecting the different forms of privilege and power can change how migrants experience accessing citizenship. There is a need for intersectional approaches that can center the voices and experiences of marginalized migrant women (Anthias). Dua reports how the policies written through the immigration process in Canada have historically showcased exclusionary practices under the “guise of inclusion” (Dua). Additionally, depending on social structures, a person who looks more like a male and has masculine qualities may experience advantages they may not have received if they held more feminine attributes. There are complex dynamics, as the intersectional approach recognizes that individuals may navigate multiple layers of privilege and oppression simultaneously, restricting their access to resources, opportunities, and social recognition.

Gender and Access to Citizenship:

Gender dynamics refers to the different interactions between individuals due to one's Gender, impacting the accessibility of citizenship rights, especially for migrating women who encounter additional difficulties and barriers in their new country. Stereotypes and discriminatory immigration laws combine and, therefore, affect the ventures of migrants. For instance, when negotiating the citizenship process, women may face significant obstacles because of administrative and legal constraints, especially regarding marriage and family reunification (Vertovec). Critical viewpoints on the many gender dimensions of US immigration rules and their effects on the lives of women moving are offered by Hondagneu-Sotelo's 2003 study. Experts may find ways to advance gender parity in immigration and citizenship processes and remove structural injustices by critically evaluating the gender-based effects of immigration laws (Hondagneu-Sotelo). Linking back to individuals who identify as intersex, they may face additional challenges related to accessing culturally competent healthcare, navigating legal frameworks that may not recognize their gender identity, and finding acceptance and support within migrant communities. Migration can amplify these challenges, as individuals may encounter many barriers that further marginalize or stigmatize their experiences (Kessler).

Institutional Responses and Policy Implications:

Considering how government policies affect immigrants' capacity to attain citizenship rights. Rules must be in place to ensure that the system is fair and susceptible for all. Such restrictions should include more gender-sensitive ways to cater to gender equality. Making sure one recognizes the unique needs and vulnerabilities of marginalized groups—i.e., migrant women and LGBTQ+ people—is crucial. The significance of incorporating gender perspectives into immigration policies and practices is highlighted by Kofman and Raghuram (2004). By considering Gender when creating policies, governments can address the unique challenges faced by migrant women or non-binary individuals. This will promote a more equal and inclusive migration system and citizenship regime. For example, such policies can help ease economic gaps between these two groups by providing financial support for household-headed immigrant women (Kofman and Raghuram). Dai Kojima explores the different kinds of ways in which queer Asian migrants navigate and negotiate their identities and desires in the context of Migration—focusing closely on the analysis of the nation of "base tactics," which means the creation and adaptive strategies employed by queer Asian immigrants for them to navigate the challenges they face. These tactics include different practices, including forming alternative kinship networks to challenge normative Gender and sexual norms, enabling people to cave out of spaces of belonging and resistance within diaspora communities (Kojima).

Anthropological Standpoints on Gender and Citizenship:

Research from the standpoints of anthropology provides valuable information by looking into the different cultural, social, and political dimensions of the gender dynamics of Migration and citizenship. Studies, including ethnographic studies, implement unique sides to experiences, showcasing the resilience and agency that migrants hold when navigating through the different challenges of the migration process while also highlighting the cultural practices that shape their identities and interactions. Such kinds of studies inspire admiration for their strength and determination. By examining the intersection of Gender, Migration, and citizenship, specialists within the anthropology umbrella can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of power dynamics, inequality, and social justice within diverse migrant communities. By considering how intersecting forms of discrimination and privilege shape migrants' experiences, researchers can determine effective strategies for promoting gender equality and social justice within migration and citizenship systems. Regarding the challenging notions of Gender and sexuality while reshaping how people understand themselves and the community they are surrounded by. Doing so helps highlight the fluidity and contingency of identity within the diaspora contexts and belonging.

Race and Ethnicity

There are 8 main types of migrants categorized by Castles (2000)(1): Temporary labour migrants – or those who migrate for employment for a temporary time period (ranging from a few months to several years); Highly skilled and businesss migrants – people with professional qualifications who move within transnational corporations or internation organisations, or seek employment internationally for their specializations; Irregular migrants – also known as undocumented immigrants, or people who immigrate to a different country without the right documentation, or overstay their permitted visiting period; Refugees – according to the UN(2), are persons who reside outside their country of nationality who is unable or unwilling to return because of a “well founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion; Asylum seekers – people who move across borders in search of protection and try to claim refugee status that may or may not be recognized by that state, however, in many conflict situations in less developed countries, it is difficult to provide asylum due to provided reason for departure and for this reason there is only a small amount of asylum seekers that are actually recognized as refugees; Forced migration – includes refugees and asylum seekers but also people who were forced to evacuate due to environmental reasons such as natural disasters or development projects; Family members – also known as family reunion migrants, are people joining relatives who have already migrated to another country under any category mentioned prior, and are able to be naturalized due to this blood relation; Return migrants – an expat who returns back to their country.

Imperialism, by its exploitative nature, has historically been a major driver of migration3. Countries that are or were taken over by colonial rule often face economic disparities, political turmoil, and social unrest, prompting their citizens to seek a better life and economic situation elsewhere and therefore is one of the main ways migrants are produced. This is a strategic way to avoid being exploited for human labour and to avoid living a worse quality of life of being subordinate under colonial rule. Racial bias also permeates immigration policies and border controls, shaping who is deemed worthy of entry and citizenship. Discriminatory practices, often rooted in historical prejudices and stereotypes, disproportionately affect marginalized racial and ethnic groups. For example, in countries like the United States, obtaining a citizenship and naturalization often involves various steps that take years to complete, and involves endless amount of red tape and bureaucracy that is usually very delicate. Dedication and proving your ties to the country is essential or you could face deportation. Further, in many other countries outside the United States, the pathway to citizenship is usually riddled with systemic barriers that perpetuate racial inequalities. Racial profiling, exclusionary laws, and disparities in access to resources especially for the colonized is usually part of every nation building process that all contribute to the marginalization of certain racial and ethnic communities. Members of minority racial or ethnic groups face more scrutiny and suspicion from colonial and settler powers, with their loyalty and belonging continually questioned. The concept of assimilation is pushed towards immigrants and minority communities to conform to dominant colonial norms, erasing their identities and protecting the racial hierarchy and the idea of an ethnocentric nation. A prominent example is the residential schooling system that were put in place in Canada and the United States that had the primary goal of completely eradicating the colonized of their culture. Ethnocentric attitudes, exemplified by the belief in the superiority of one's own ethnic group, contribute greatly to the marginalization and exclusion of minority populations. Ethnocentric policies and narratives strategically frame migration as a threat to national identity and security, fueling xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment. Ethnocentric biases shape immigration policies, favoring individuals from the settler/colonial groups while restricting or demonizing the colonized. The notion of racial homogeneity has long been used as a tool for nation-building, promoting the idea of a cohesive and unified national identity based on shared racial or ethnic characteristics(4). However, this ideal is objectively a myth, and is constructed to justify exclusionary practices and maintain power dynamics.

Attempts to achieve racial homogeneity through policies such as assimilation, segregation, or genocide have resulted in deep rooted social injustices and human rights violations. Some policies go as far as excluding immigrants from forming unions with anyone from the settler race (5). The quest for racial purity undermines cultural diversity and denies the contributions of immigrants and minority communities to national development. The concept of race has scientifically been argued to be a social construct (6), shaped by historical, cultural, and political factors rather than biological differences. The case of early Chinese immigration to Canada exemplifies how racial categorizations can evolve over time and vary depending on social contexts. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese immigrants to Canada were perceived as racially inferior and subjected to discrimination and prejudice. However, as they assimilated into Canadian society and achieved socioeconomic success, they were gradually accepted as on par with the dominant white race and integrated more into society.

Class

The intersection of class and migration plays a significant role in shaping experiences, opportunities, and challenges for individuals seeking citizenship in a new country. Class dynamics, including socioeconomic status, wealth, and access to resources, greatly influence the migration process and subsequent pathways to citizenship. Capital (what defines one's class) can be defined not only by economic capital but also by linguistic, cultural, and social capital. To understand the positions of different migrant groups in the global hierarchy we must look at the type and amount of capital they hold. The upper classes hold all forms of capital and resources: Property, businesses, connections, access to social networks, etc. Therefore, they make the perfect example for international mobility because they can make their home out of anywhere in the world, experiencing smooth transitions. Meanwhile, lower-class migrants who haven't had access to education and don't possess economic assets or social/cultural capital experience way more barriers to integration. Social and humanitarian rationales for the admission of migrants have increasingly made way for economic rationales focused on class, productivity, and other capitalist ideas.

Class can be in itself the driving factor for immigration, it determines the conditions that may drive people to want to leave their homelands. As we've seen before, the factors that lead someone to migrate can be economic ones. Be it looking for job opportunities or fleeing from a crashing economy, many people leave their home countries to look for economic ascension. This is especially true in colonized countries that had their resources and labor stolen and exploited. The people of these countries are often the ones who need to pursue migration for economic reasons, as class hierarchy doesn't exist solely within national borders, but amongst countries as well.

There are many examples of mass migration movements throughout history that exemplify that, like the wave of Asian immigration to white settler colonial Canada. Then, Asian workers were called to help build the surging nation and later their position as low-class workers enabled the Canadian state to dictate their migration rights without resistance. Although they were called to the new coming settler nation, it didnt mean they were incorporated as part of its society, as only their labor was necessary. What happened was that the demands of the emerging capitalist economy led to them being temporarily able to immigrate there.

Class can also create or remove barriers to attaining citizenship. It can create obstacles as class disparities mean that lower-income migrants may face challenges in meeting residency requirements, language proficiency (and its exams, which for the most part cost money), or financial obligations associated with naturalization processes such as fees and income requirements.

Currently, the very access to citizenship is stratified according to class, as conceptions of “integration” assume that migrants will or should fit into “middle-class” conceptualizations.

There has been a global trend of increasingly restrictive economic criteria for naturalization, and in the current dominant political climate has been selling the idea of citizenship as a reward, something to be conceived not as a basic right enabling integration but as reserved for those who prove themselves to be “deserving” and rightfully belonging to the correct class. These unwanted migrants are deemed to be unfit for “integration” because of their class.

Class structures the resource inequalities that separate those who are able to migrate from those who lack the necessary means and resources. Class dynamics can also influence the choice of migration channels or means, shaping citizenship policies and practices. Governments may implement eligibility criteria that inadvertently disadvantage lower-income migrants, meanwhile, higher-income individuals have access to legal migration pathways such as work visas or investor programs — over twenty countries have Citizenship Investment programs, in which those who invest a lot of money in a country receive benefits like long term residency and in some cases even eventual citizenship — while lower-income individuals may resort to irregular or undocumented migration routes out of necessity. Higher socioeconomic status also often correlates with greater access to legal resources and support, enabling affluent migrants to navigate complex immigration systems more effectively and know/assert their rights during citizenship processes. These class-based disparities in access to citizenship can have broader implications for social cohesion and inclusion, as unequal access to rights and privileges may exacerbate tensions and inequalities within society.

Class can shape migration policies and how they affect people, as they aim to reproduce the values of a society and define the insiders and outsiders of a nation.

Although the admission of migrants and refugees should be based on international understandings of fundamental human rights, in the current neoliberal global climate the economic criteria are given more importance. What should be a selection grounded on humanitarian views is actually based on class. This becomes especially clear in discourses such as selecting “the best and the brightest” out of the migrant population, solely to satisfy the needs of the economy.

Analyzing and understanding the role of class in this phenomenon sheds light on the current myth of meritocracy that commonly accompanies the selection processes in migration policies. These rhetorics make it so that marginalization is no longer understood as a social injustice that should be remedied by the state, but rather as a result of cultural incompatibility and private failure, and should be punishable by denying access to the desired society. A migrant's value isn't determined by a genuine assessment of merit, (which would require comparing the social position from which an individual came, with the social position they reached through their effort) but instead on how they would benefit the receiving country's economy.

Seeking asylum (especially in the global north) can be extremely costly and strict for international migrants. In some cases for lower-class people marriage can be a more accessible option for immigrating to first-world countries, but even that comes with being constantly demonized by the local government and society, which constantly targets them with elitist (and a lot of times racist/xenophobic/sexist) regulations. Again we can see settler colonial states dictating what is a “good” migrant or citizen.

Understanding the role of class in migration and citizenship is essential for developing inclusive policies that promote equality, social justice, and the full integration of diverse populations into host societies. Addressing socioeconomic disparities and barriers to citizenship can foster more equitable opportunities for all migrants, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

Sexuality

In the complex dynamics between migration and sexuality, the colonial influence of heteronormative nation-building continues to be present. This impacts the experiences of queer individuals, as they migrate in search of community and acceptance. The era of imperialism introduced colonial structures, upholding patriarchal and heteronormative ideals around the world. Colonizers brought these ideals into their nation-building, positioning heterosexual relationships as the standard, and marginalizing deviant identities. State control of marriage and sexuality played a vital role in colonial nation-building and assimilation, continuing to impact marginalized communities. One manifestation of these ideals was the domination over colonized women as a form of asserting ownership over the colony. The system of concubinage was heavily promoted, which pairs a European man with an oriental woman cohabiting in a family structure. The sexuality of these racialized women was emphasized, as they were viewed as objects to be possessed. This system enforced oppressive heteronormative gender roles on colonized women, who provided free domestic labor for their male partner. Additionally, the concubinage system ensured they men wouldn’t engage in deviant behavior, such as homosexuality or relations with prostitutes. This upheld the heteronormative standards of colonial society. State control played a crucial role in assimilation of Indigenous people through creating heteronormative ideals of sexuality. Colonizers imposed the patriarchal heterosexual nuclear family structure- a husband, a wife and children- as the standard familial unit. These structures disrupted previous structures of relationships, policing deviant sexuality through the legal regulations of marriage. This enforced a capitalist system, encouraging marriage to purchase a home and to raise children to contribute to the workforce. Colonizers aimed to undermine existing social structures and customs, and impose their own values onto colonized societies to create a nation to their own ideals. Hegemonic heteronormativity created lasting systems of oppression and discrimination that continue to isolate individuals based on sexuality.

In contemporary times, the impact of heteronormativity on migration is still evident. Assumptions of migrants as heterosexual, cisgender men persist, shaping policies and standards around immigration. As fathers and men are patriarchally viewed as strong providers for their family, this perpetuates heteronormativity in migration. Male bodies are valued in the capitalist economy, and heteronormative society encourages having children to contribute to the workforce. This leads to the marginalization of queer migrants, facing additional challenges in their process of adapting to a new country. The enforced heteronormativity of migrants renders less desirable individuals to the nation as second class citizens. Transgender individuals face significant difficulties in the migration process, and Canada’s immigration laws had historically claimed homosexuality as immoral deviance and grounds to not allow entry to the country. Deviance in sexuality is a weaponized tool for control, often against migrant communities. In Australia, the criminalization of forced marriages is a racialized issue disproportionately targeting immigrant communities. Through policing and stigmatizing of immigrant sexualities and relationships, migrants are stigmatized and scrutinized. Authorities overlook the complexities of coercion and consent in forced marriage, but perpetuate narratives of migrant women as victims to migrant men. The policing of intimate lives of migrants in the name of morality and liberation of women effectively isolates and causes further discrimination against them. This criminalization of sexuality encourages exclusionary practices of immigration, by framing it as a foreign issue. Queer individuals may migrate to Canada for a multitude of reasons. Migrants from other countries seek asylum in Canada in search of queer community and social acceptance among peers. Furthermore, migrants may be escaping oppression and discrimination for their sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics, also known as SOGIESC. Social stigma, criminalization, or lack of access to healthcare and resources may cause one to seek refuge in another country. As a result, many individuals leave their home countries and seek asylum elsewhere.

The queer migrant identity challenges the heteronormativity, gender roles, and socioeconomic structures ingrained in a colonial nation. Heteronormative, cisnormative and patriarchal frameworks lead to persecution of deviance, as homosexual and transgender identities are targeted and criminalized in many countries. 71 countries have anti-homosexuality laws, and transgender identities are criminalized and regulated under ‘cross-dressing’ laws in 13 countries. Queer individuals have a higher chance of being targeted by hate crimes and discriminatory practices, as their lives are regulated by state and society. Only 36 countries recognize same sex marriages, causing queer couples to migrate to get married. Queer migrants seek out urban centers such as Vancouver in countries that don’t criminalize queerness as a safe space to express their identities. Migration is the only way for persecuted queer individuals to live openly, without fear of harm such as discrimination or imprisonment. Migration can provide a feeling of empowerment and freedom for individuals. In urban centers like Vancouver, there are large and vibrant LGBTQ+ communities and dedicated queer spaces such as Pride Parades and centers providing resources for queer resources.

Moving to a country with a prominent LGBTQ+ presence provides migrants the opportunity to connect with other queer individuals, and access vital support and resource networks. Queer focused support and resource networks may include healthcare, mental health support and legal assistance. These resources are vital to the physical and mental well-being of an individual. Additionally, the creation of queer friendly spaces, which may be marked by pride flags, public artwork, and LGBTQ+ events, fosters a sense of belonging and empowerment. Through a queer supporting environment, these spaces enable migrants to feel empowered and accepted by their new community. The intersectionality of race and sexuality for queer migrants complicates the experience of racialized migrants. In LGBTQ+ spaces, racialized individuals feel excluded and undesirable, as the communities are primarily white. This creates a disconnect between the experiences of white queer individuals with those of racialized ones, who undergo additional levels of discrimination. Similarly, in their own migrant communities, queer individuals face stigma due to cultural norms and prejudice. These individuals feel a sense of peripheral belonging in their communities, not feeling included in the queer community but still part of it. To combat this marginalization, queer racialized individuals engage in space making, creating their own space to explore their identity. This tactic allows for everyday survival and contributes to the possibilities for queer future in their community.

References

- Anthias, Floya. “Intersectional What? Social Divisions, Intersectionality and Levels of Analysis | Request PDF.” Researchgate, 2013, www.researchgate.net/publication/258136462_Intersectional_what_Social_divisions_intersectionality_and_levels_of_analysis.

- Dua, Enakshi. “Exclusion through Inclusion: Female Asian Migration in the Making of Canada as a White Settler Nation | Request PDF.” Researchgate, 2007, www.researchgate.net/publication/249041255_Exclusion_through_Inclusion_Female_Asian_Migration_in_the_Making_of_Canada_as_a_White_Settler_Nation.

- Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette. “Gender and U.S. Immigration.” University of California Press, 2003, www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520237391/gender-and-us-immigration.

- Kessler, Suzanne J. “The Medical Construction of Gender: Case Management of Intersexed Infants.” Canvas, www.researchgate.net/publication/249107815_The_Medical_Construction_of_Gender_Case_Management_of_Intersexed_Infants. Accessed 13 Apr. 2024.

- Kofman, Eleonore, and Parvati Raghuram. “Gender and Global Labour Migrations: Incorporating Skilled Workers.” Antipode, Wiley-Blackwell, 3 Sept. 2021, www.academia.edu/1545643/Gender_and_Global_Labour_Migrations_Incorporating_Skilled_Workers.

- Kojima, Dai. “Mobilities-in-Difference and Basue Tactics in Queer Asian ...” Canvas, 2014, www.researchgate.net/publication/265949664_Migrant_Intimacies_Mobilities-in-Difference_and_Basue_Tactics_in_Queer_Asian_Diasporas.

- “Steven Vertovec.” Steven Vertovec | Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, 2007, www.mmg.mpg.de/steven-vertovec.

- https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/where-immigrant-students-succeed_5l9x0xmhswr1.pdf

- https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-are/1951-refugee-convention

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09663690701439751

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/645114

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8452910/

- https://metropolitics.org/Migration-and-Inequalities-The-Importance-of-Social-Class.html

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/imig.12469

- https://qz.com/2004229/how-the-wealthy-seem-to-immigrate-as-they-please

- LaViolette, Nicole. “Coming out to Canada: The Immigration of Same-Sex Couples under the ‘Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.’” 2004. MCGILL LAW JOURNAL, vol. 49, no. 4, McGill University Faculty of Law, 2004, pp. 969–1003, https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20221006075451.

- Luibhéid, Eithne. "Queer/Migration: An Unruly Body of Scholarship." GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 14 no. 2, 2008, p. 169-190. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/241318.

- Stoler, Ann L. “Making Empire Respectable: The Politics of Race and Sexual Morality in 20th-Century Colonial Cultures.” American Ethnologist, vol. 16, no. 4, 1989, pp. 634–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/645114. Accessed 13 Apr. 2024.

- https://open.substack.com/pub/kimtallbear/p/love-in-the-promiscuous-style?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web