Anti-Black Gendered Racism

Anti-Black gendered racism is a structural form of racism that refers to the simultaneous experience of sexism and anti-Black racism. In Canada, Anti-Black gendered racism occurs in many forms and is deeply embedded in Canadian policies, practices and institutions [1]. Because of Canada's colonial history, and involvement in the Trans Atlantic Slave trade, Anti-Black gendered racism has served both historically and presently as a cornerstone of Canada's foundation. Therefore, due to its omnipresent nature throughout history Anti-Black gendered racism has been normalized in Canada and often remains invisible to society at large, which discredits the experiences of those who have been exposed to it [1]. This lack of recognition also presents significant challenges when trying to challenge, change or shed light on instances of Anti-Black gendered racism in Canada on both a collective, and individual level.

Globally, Canada is regarded as an incredibly tolerant, and multicultural nation. Canada's history of segregation and involvement in the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade is relatively unknown, and most often excluded from discourse regarding Canadian history.

Terminology

Anti-Black Gendered Racism

Anti-Black gendered racism can be defined as a form of racism that occurs in both a gendered and racialized manner. Anti-Black racism is the way in which people of African and/or Caribbean descent are targeted via Canadian institutions, practices and beliefs that reinforce racist ideologies, prejudices, and discrimination directed at people of African and/or Caribbean descent based on their race and ancestry [1].

Gendered Racism

Gendered racism is a sociological term originally coined by Philomena Essed, which refers to the ways in which racism and sexism intersect in order to negatively affect women of colour and people of colour who do not conform to the gender binary. Gendered racism can take many shapes, and works institutionally, systematically and personally through the use of stereotypes and racist ideologies in order to disadvantage and oppress certain demographics.

Anti-Black Racism

The term Anti-Black racism is associated with the work of Dr. Akua Benjamin, a social work professor at Ryerson University in Toronto. Dr. Benjamin uses the term in order to refer to the ways in which African/Black Canadians experience racism, taking into consideration African/Black Canadians histories of enslavement, as well as Canada's history of colonization [2].

Racial Stereotype

a racial stereotype is a preconceived notion or idea one has about an individual, or a group of individuals based on their race [3]. Examples of stereotypes commonly attributed to African/Black women are that of the Angry Black Woman, the Mammy, the Jezebel, and the Welfare Queen. These stereotypes are used as a form of racial control, and are damaging to individuals sense of self, and perception of others.

Origins

Canada prides itself on its multicultural national identity. The idea of Canada as a cultural mosaic, where individuals from various racial and ethnic backgrounds coexists in peace is one that is widely accepted globally. The idea of Canada existing as a multicultural safe haven for minorities can be widely attributed to changing policies on immigration and citizenship implemented by the Canadian government due to an influx of immigrants to Canada during the 1960's [4]. However, the Canadian national identity does not reflect the realities of Canadian history, and despite Canada's multicultural and accepting appearance, racist does persist in Canada in a myriad of ways. Many of these racist discourses and instances are hidden from dominant discourse and Canadian history, and have hidden behind the creation of Canada as a multicultural safe haven.

Slave Trade in Canada

Anti-Black racism is often seen as a relatively new phenomenon in Canada, something that is the exception rather than the norm. However, Canada has a persistent, long standing history of racism, including Anti-Black and Anti-Black Gendered racism [5] Although in Canada, knowledge of the United States history of slavery and segregation is widespread, there is little recognition of Canada’s role in slavery, despite the fact that slavery existed in Canada pre-federation for over 200 years [5]. Slavery was a system of racial control, that was used to dehumanize and commodify African/Black men and women for profit, and for labour. The legacy of slavery can still be seen throughout Canadian culture, through the representation of African/Black men and women in dominant media, through the rates of incarceration in prisons, through educational outcomes of students based on race, and through racial profiling and police violence in Canada [6]. Anti-Black racism, and Anti-Black gendered racism operate through policies, practices and beliefs that are rooted in the experience of colonization and enslavement here in Canada. Its legacy can be seen through the current unfair social, economic, and political discrimination and marginalization faced by those of African/Black descent in Canadian society[1].

Stereotypical Representations of African/Black Women In Media

African/Black women are denied subjectivity and forced to conform to several stereotypes perpetuated in dominant discourse and mainstream media [7]. These stereotypes are prevalent globally, however they are often curated through media and discourse prevalent in North America. Practices of representation, especially visual representations of African/Black women in media perpetuate racist stereotypes in society, and deny African/Black women the subjectivity to create and come to terms with aspects of their own identities by themselves [8].These stereotypical representations are seen constantly in mainstream media and dominant discourse, through the representation of African/Black women in Hip Hop music, in sports, and in politics.

These representations also reinforce and normalize racist ideologies and stereotypes among society, allowing for forms of everyday Anti-Black Gendered racism to go unnoticed, as they are seen as biological fact, and not the perpetuation of racist ideals [9] .

Systemic Forms

Criminalization & Incarceration

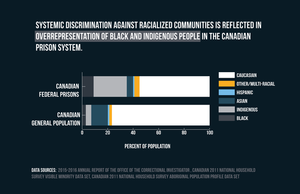

In Canada, various sets of data collected demonstrate that African/Black-Canadians are disproportionately overrepresented in Canadian prisons. African/Black-Canadians account for ten percent of the Canadian prison population, while comprising just only three percent of the Canadian population [10]. Despite the denial of racism in Canada, African/Black-Canadians are more overrepresented in Canadian prisons, that African/Black-Americans are in American prisons [10]. A lack of data collected on African/Black-Canadian women makes it difficult to know how this demographic is specifically targeted and incarcerated by police, however studies have demonstrated that Black women and girls are one of the fastest growing incarcerated groups in Canada[1] and the African/Black-Canadian women who are incarcerated in Canada are most often done for non-violent drug offences [11]. Canada's over-policing of Black and Indigenous peoples can be demonstrated through the overrepresentation of racialized communities in the Canadian Prison system [12]

The over-policing of African/Black-Canadians can be demonstrated through data collected by the Toronto Star, which demonstrates that African/Black-Canadians on average were 3.2 times more likely than their White counterparts to be carded in Toronto. Carding refers to being stopped by police on the street without probable cause, asked to present identification and prove their identity using a police database [13]. Barely any data that demonstrates racial disparity among carding in Canada is available, as Canadian police departments actively suppress the collection of racial data on police interactions [13].

Education & Employment

Anti-Black Gendered racism can be demonstrated through the educational and employment opportunities given to African/Black-Canadian men and women. The stereotypes and stigmas embedded in Canadian society affect the present day opportunities of those of African/Black-Canadians. African/Black-Canadians are likely to be placed into foster care, or streamed into less rigorous academic programs [14] . 8.8% of African/Black-Canadian women with postsecondary degrees are unemployed, while only 5.7% of white-Canadian women with high school diplomas are unemployed (https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-anti-black-racism-strategy). While the general Canadian populations unemployment rates sits at 7%, African/Black-Canadian women are unemployed at 11% [14]. While employed, African/Black-Canadian women make 15% less than their white female coworkers, and 37% less than white men [1]. Furthermore, results from a survey conducted in the Greater Toronto Area demonstrated that one third of African/Black-Canadians had experienced challenges at work they believe are associated with their race, whether it be feeling discomfort, or outright racism [15]

Health & Wellbeing

The consequences that Anti-Black Gendered racism has on the health of African/Black-Canadian women is profound. A 2003 study demonstrated that one in five African/Black-Canadian women encountered racism within the health care system, whether it be ignorance or cultural insensitivity on behalf of health care providers, inferior quality of care, being overcharged for services, or being called racial slurs [15]. Anti-Black Gendered racism experienced through the healthcare system is one aspect of the various ways that Anti-Black Gendered racism operates in Canada, as one’s educational attainment and employment affect one’s access to health care, which affects an individual's overall health [15]. As has been previously demonstrated, African/Black-Canadians are disadvantaged at both work and school due to systemic forms of Anti-Black racism, which therefore have negative consequences for the overall health and wellbeing of said demographic, on both an individual and collective level [15].

The Intersection of Race and Gender

Intersectionality is a term that was famously coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the late 1990’s, and refers to a theoretical and analytical tool used in order to understand how various systems of oppression intersect, and affect individuals differently based on factors such as race, gender, class, sexuality and ability [16]. It has now become a term liberally used in discourse regarding oppression in both media and academia, and has been used in the creation of various social movements in order to attempt to shift hierarchies of power, and challenge how they produce and reinforce systemic forms of oppression [16]. Crenshaw's explanation of the concept of Intersectionality can be helpful in understanding how Anti-Black Gendered racism operates, as she demonstrates using concrete examples how gender and race intersect in order to disadvantage women of colour [17].

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 The City Of, Toronto (December 5, 2017). "Toronto Action Plan To Confront Anti-Black Racism" (PDF). www.toronto.ca.

- ↑ Black Health Alliance (2018). "Anti- Black Racism". www.blackhealthalliance.ca. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ↑ Canada, Historica. "Stereotyping". www.blackhistorycanada.ca.

- ↑ Burnet, Jean (June 27, 2011). "Multiculturalism".

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Maynard, Robyn (April 24, 2018). "Over-policing in black communities is a Canadian crisis, too". www.washingtonpost.com.

- ↑ Hawkins, Kate (October 2, 2018). "Q&A: Author Robyn Maynard on Anti-Black Racism, Misogyny, and Policing in Canada". www.canadianwomen.org.

- ↑ Wilson, Brian; Sparks, Robert (November 1999). "Impacts of Black Athlete Media Portrayals on Canadian Youth". Canadian Journal Of Communication. 24 – via CJC Online.

- ↑ Hall, Stuart (October 2006). "Representation & the Media: Featuring Stuart Hall". www.youtube.com.

- ↑ Henry, Annette (1993). "Missing: Black Self-Representations in Canadian Educational Research". Canadian Journal of Education. 18: 206–222 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McIntyre, Catherine (April 21, 2016). "Canada Has a Black Incarceration Problem". www.torontoist.com.

- ↑ Press, Jordan (February 14, 2018). "Canada must tackle racism in federal prisons, Senate committee hears". www.ctvnews.ca.

- ↑ Chan, Jody (July 17, 2017). "Everything you were never taught about Canada's prison systems". www.intersectionalanalyst.com.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rankin, Jim (March 9, 2012). "Known to police: Toronto police stop and document black and brown people far more than whites". /www.thestar.com.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Government, Ontario (August 23, 2018). "Ontario's Anti-Black Racism Strategy". www.ontario.ca.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Eternity, Martis (March 20, 2018). "The Health Effects of Anti-Black Racism". www.thelocal.to.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1989). "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics". Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics – via Chicago Legal Forum.

- ↑ Vasquez, Alejandra (October 27, 2016). "The urgency of intersectionality: Kimberlé Crenshaw speaks at TEDWomen 2016". www.blog.ted.com.