The Orchard Garden

History of the Garden

The LFSOG had its beginnings in the spring of 2007 as the “LFS Garden at MacMillan Building (LFSGAMB),” a directed studies project by former Global Resource Systems (GRS) student, Lin Steedman (2007). Her project began the cultivation of an area of land on the south-side of the MacMillan Building in order to establish an edible food garden (Steedman, 2007). Her project began laying the foundations for what was to later become the LFSOG. In the winter of 2007, a scenario was presented to student groups in the AGSC 450 class to further research the enhancement and expansion of the LFSGAMB. In the spring of 2008, portable classrooms were removed from an area of land on the west-side of the MacMillan building allowing for expansion of the garden. This area was tilled and seeded with two varieties of potatoes (Cal-White and Pontiac) in early April 2008. Potatoes were chosen as the initial crop to provide an indication of the soil’s quality and production capability (Group 17, 2008). This expansion plot as well as the existing LFSGAMB were then merged and renamed the LFSOG to reflect the area’s history as prior apple orchard land. Between January 2009 and May 2009, the AGSC450 students used the garden as a project scenario in conjunction with Andrew Riseman and Eric Drewes. A fence was developed to define the garden’s boundaries and encourage a sense of community place. In the summer of 2009, the garden was granted funding through the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems at the UBC Farm to hire a work-study student to coordinate the garden starting in June. Secured funding allowed the garden to develop its production scheme and harvest log to produce a larger variety of produce, engage volunteers in the garden, and commence the development of communications and marketing materials.

(adapted from "TOG Management Handbook - 2012" by Natasha Tymo and Jay Baker-French)

Introduction to the 2013-2015 Team

Claire McGillivray completed her first year of Environmental Sciences at McGill University. After taking a year off to travel through Europe for four months, she transferred to the University of British Columbia for the Global Resource Systems program. While she has always been interested in gardening, her passion for farming and food systems began during her first year in the GRS program, and grew stronger after working for a summer as a farm intern at the Richmond Sharing Farm, a community-oriented, non-profit farm focused on growing food for the Richmond Food Bank. Throughout her first and second years at UBC, she was involved with the Orchard Garden, whether through volunteering or attending events. In the summer of 2013, she was offered the job as Orchard Garden production coordinator, a position which she held until her graduation in December, 2014.

Galen Taylor Jones developed an interest in sustainable agriculture while traveling in New Zealand and working on farms. She then began a degree at City College of San Francisco before transferring to UBC, where she found the Land and Food Systems faculty. In this undergraduate degree she has focused on agro-ecology, while in the future she hopes to move towards the communication of food/ agricultural/ environmental knowledge in a masters degree. She has been engaged with Orchard Garden projects and community throughout her time at UBC, and began formally working as a production coordinator for the Garden in September of 2013. She will be leaving the position in April of 2015. She has also worked since 2012 with Inner City Farms, interned at the UBC Farm and worked on farms in her home state of Vermont. If she could grow only one annual crop, it would be garlic!

History of the Transition

In the fall of 2013, plans were made public to develop the original Garden site into a private college for international students. Vantage College will serve as an alternative first year experience and focusses on first year classes paired with intensive English preparation.

The original site had always been stated as a temporary site, and the Orchard Garden team therefore elected not to launch an organized protest. However, this decision was not made without internal conflict and uncertainty. While officially the site had always been zoned for development, the inevitable nature of a garden is that a connection is developed to the land. The countless hours of hard work by the Orchard Garden community created a tangible space that was important to many people. However, in order to maintain a positive relationship with Campus and Community Planning (C&CP), the Orchard Garden team was advised to avoid protesting. Rather, a dialogue was begun to brainstorm a new site for the garden. Campus and Community Planning was clear that temporary gardens would not be permitted on campus in the future, owing to a sense of entitlement they perceived the O.G. community to have developed around the original site. After months of meetings, the Orchard Garden was given a permanent plot of land in Totem Fields. While the proposed area was relatively the same size as the original site, ensuing restrictions were placed upon the area, and the finalized space is significantly smaller (4000 ft^2, or 370 m^2). The rectangular space, which is oriented lengthwise from East to West, is adjacent to Forestry and Biology research plots at Totem fields.

Administrative

The stakeholders of the garden include Work Study students, graduate students, representative professors and student volunteers from Land and Food Systems and Education faculties. To ensure that there is communication between the Education and Land and Food Systems team members, all-team meetings are held regularly. Depending on the season, frequency of meetings varies from once per week to once per month. In general, Land and Food Systems students are responsible for “production” while Education team members are responsible for “programming,” with overlap in these duties. These meetings are also important for discussing funding and grants for the Orchard Garden.

The majority of our work as the Production team managers was self directed. Most tasks were completed together, and neither of us was solely responsible for any one aspect of production. We met regularly to coordinate daily tasks and goals for the coming weeks and months. In the summer of 2014, two interns were hired from May to August through a Canada Summer Jobs grant. These two interns worked primarily with us in the Garden, and we were responsible for providing them direction when possible.

Aside from physical farm labour, one of our main administrative tasks was organizing outlets for the food we grew. We did this primarily by using sources that had purchased from the Orchard Garden in the past, especially groups that are part of the Land and Food Systems Faculty. The most common way that we organized these groups was through our Gmail account. We would confirm orders, as well as schedule pickup or delivery times. We also used Gmail to contact faculty members, employees at the farm, or anyone outside the UBC community. We had a list of volunteer emails that we would continually add to; we used this list when sending out mass emails in order to organize volunteer work days.

Another part of our online administrative work was upkeeping the Orchard Garden Facebook page. This included posting photos and updates, creating events and promoting our market stand. We also used the Facebook page as a space to communicate with volunteers about work parties. We found that consistent posting was extremely important for increasing our reach. Posting pictures was also an effective way to gain public interest in the Facebook page. We would recommend making posts once per week in order to keep a strong online presence.

Finally, we were responsible for recruiting new volunteers. This consisted of talking to classes in the LFS faculty, advertising on our Facebook page, and speaking at events like the Applied Biology Information Session. Once volunteers were recruited, we were responsible for organizing times to meet at the garden, and providing instruction and supervision during work parties.

Garden Design

As soon as the Totem Field location was guaranteed from Campus and Community Planning (C&CP), we began sketching designs for the garden layout. Two students from the Sustainable Architecture and Landscape Architecture (SALA) program, An Na and Yiwen Ruan, consulted with the Education Team and contributed design input in the initial stages. Their focused on the movement of people around the site, and they added valuable ideas on how to create gathering spaces within the garden. From their draft designs, we (Galen and Claire) took inventory of the existing perennial plants at the old site and arranged them based on space constraints and agroecological principles. Next we designed the placement and orientation of the annual crop beds, based on previous farming experience, aesthetic appeal, and ease of access.

However, during the design and implementation process, there were many limitations and barriers we encountered, which required us to constantly re-evaluate our design. The first was the uncertainty of the new site’s boundaries. Based on limitations from C&CP, the garden could only be located on land that was zoned as “green academic”, and was not slated for development in the future. Confusion surrounding the exact location of our northern boundary meant that our proposed plot was cut approximately in half. In addition, a large grass strip needed to be maintained through the middle of the space, allowing for a mower or other field machinery to be driven through. Seane Trehearne, the manager of Totem Fields, allowed us to place a shed outside of our zoned perimeter, as well as an adjoining gravelled area for washing/processing vegetables. Water source was also a consideration in this placement; the processing area is proximal to the site’s closest tap.

We wanted to use as much of our pre-existing infrastructure as possible. The MacMillan site contained wooden benches, picnic tables, large wooden trellises, espalier posts, a three-bin compost system, and wooden boxes encasing fruit trees. We were not able to bring all of these with us, but managed to incorporate the majority of them into the Totem site. Because of the reduced footprint of the garden, it was important to carefully plan structure placement and critically evaluate the use of each item we brought with us.

The MacMillan site also held three bee hives which required particular consideration in their relocation. Totem Field is primarily a research site, some trial areas require the spraying of various pesticides, and we were apprehensive about their effect on the bees’ health. To investigate further, we obtained a list of common pesticides used at Totem, and contacted a bee researcher from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada about their potential harm. The active ingredients were all considered to be relatively benign.

| Product | Active Ingredient | Total Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Aliette (F) | Fosytyl 80% | 240 g |

| Roundup (H) | Glyphosate | 500ml |

| Safers Soap (P) | Fatty Acids & Potassium salts | 425ml |

There was concern that, upon moving the hives, foraging bees would return to the old location of their hives. This may happen when hives are moved more than a few feet but less than several miles. To help the bees reorient themselves, we placed tree branches in from of hive entrances for the first few days after the move [1].

In planning the move of the bees, we also consulted a student-team that had been recently involved with beekeeping at the garden. Faculty members such as Martin Hilmer and Will Valley were extremely helpful in both the physical move of the hives and as resources for questions we had.

With all these considerations in mind, we began the practical implementation of the design in April. First, the entire site was rototilled by the Totem Field Manager, Seane Trehearne. We next had a load of mushroom manure delivered, which was spread manually with help from the Global Resource Systems (GRS) class. Seane next re-tilled the site to mix in the manure. Based on our previous farming experience, we measured beds that were three feet wide, using one foot wide paths [2]. This layout was first marked with lengths of string and then dug manually. To allow for wheelbarrows and easy movement, we designed our main pathways to be three feet wide.

Production

Much of our garden knowledge was based on previous gardening and farming experience. We also used several gardening books that were valuable research. When we had a specific question or problem, we would also use extension papers and gardening forums on the internet.

Perennials

Generally, we planned to plant perennials along the Garden’s edges. This allows for more flux from year to year in annual bed design, creates a hedgerow-like border to the garden, and distinct spaces for annuals and perennials, which have different maintenance needs. Some perennials had specific structural requirements, which we integrated into our design.

Many of our perennial trees had been established on an espalier (apples, Asian pears and grape vines) - trained along wires to maximize fruit production. In designing the Totem Orchard Garden, we followed the model of the original garden and kept our espalier structures on the space’s perimeter. Hops, honeysuckle and clematis are all vines that that thrive on trellises – this was also incorporated into our perimeter design for perennials.

Three persimmon trees were contained in wooden boxes at the MacMillan site. These had to be disassembled when moving the trees to the new site. Reconstructing the boxes was unrealistic, and their primary value was aesthetic, so the persimmons were planted directly in the ground. There were two large apple trees at the MacMillan site that had served as reminders of the site’s history as an orchard. Though these beautiful old trees were too large to be transplanted, we grafted scions from their branches onto dwarf root stocks. These grafted saplings were brought to Totem Field.

At the MacMillan site, the herb garden was separated from the rest of the garden and was therefore somewhat neglected. At the Totem site, we tried to give the herb garden a greater presence. We chose to situate the herbs near the bee hives, as many herbs provide forage for bees, and the low maintenance needs of perennial herbs meant there would be less disturbance near the hives. Plants in the herb garden include: lavender (two varieties), catmint, peppermint, spearmint, lemon balm, dill (2 varieties), curry plant (Helichrysum), purslane, borage, oregano, thyme, chives, sage (2 varieties), cilantro.

The Chinese Market Garden and the Native Plants Garden existed within the MacMillan site as distinct areas, and required particular consideration in their re-location. These areas were designed to highlight different garden histories in British Columbia. The Chinese Market Garden was established to encourage conversations about the history of Chinese immigrants to Vancouver - in particular, the role of Chinese immigrants as farmers who provided a majority of the produce for the Lower Mainland in the early 20th century. Likewise, the Native Plants Garden is meant to emphasize plants that may not be commonly grown in vegetable gardens, but are native to this region and may be of importance to Musqueam or other First Nations. Additionally, having both of these gardens serves as a reminder of the historical connection between Chinese and First Nations people in Vancouver resulting from shared histories of land use, oppression, displacement and discrimination.

While almost all of the perennial plants from these gardens were moved to the Totem site, we faced issues in the full re-establishment of the spaces. One of the major problems we encountered was the lack of involvement of either Chinese or First Nations community members. We worried about misrepresenting either historical or current experiences, and we were unsure whether we were making false cultural assumptions. We weren’t clear whether the Native Plants garden was intended to represent the culture of Musqueam peoples, First Nations peoples in general, or to simply highlight plants native to the British Columbia. In addition, we were critical of past practices of growing exclusively “Chinese” vegetables in the Chinese Market garden. Chinese immigrants often grew a wide variety of vegetables that may or may not have originated in China. Therefore, in our design of the Totem site, we allocated a space for potential use as a Chinese or Native Plants Garden, but did not feel comfortable fully re-establishing the gardens ourselves.

Annuals

Having placed our perennials, the remaining space in the garden was intended for annual beds. Based on previous gardening experience, we designed these to be three feet wide, separated by one foot wide paths. In addition, our design aimed to make irrigation functional. We faced a compromise between maximizing sun access and bed square footage: East-West oriented beds will not shade each other out, while longer North-South beds minimize paths therefore maximizing growing space [2]. We decided to create both EW and NS beds, as can be seen in our garden design diagrams. Particularly given that the Garden space is much smaller than the old site, we felt a combination of bed orientations made the space more interesting and heterogenous.

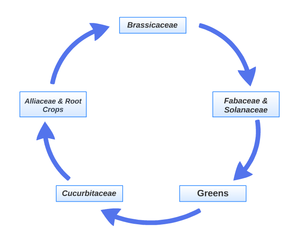

Crop Rotation

In a crop rotation, the location of annual vegetables within a production space is systematically changed from year to year, often following principles of soil management. Vegetables can be grouped by botanical family, or by management requirements. There are many different factors to consider when designing a crop rotation plan. It is unrealistic to try and accommodate all of them, and so we chose some that we felt were most important. Since Brassicas are heavy Nitrogen feeders, we followed this section with Fabaceae plants in our plan, which fix nitrogen into the soil. As root vegetables are often unable to compete with weeds, we preceded roots with Cucurbits, whose large leaves help to suppress weeds [2].

While in an ideal situation, the crop rotation plan would be a strict blue-print for future planting, there are many obstacles in implementation. Some vegetables are quick to mature, and require several plantings (or successions) each season, while others require an entire season before they are ready to harvest. These successions do not always match up with when a rotation is supposed to begin. In addition, not all “families” or groups of vegetables are in equal demand. Our desire to have a wide variety of plants sometimes conflicts with market outlets. We were also limited by the small area of the garden. Within such a small and organic production site, we feel that the simple practice of rotating crops is sufficient to maintain soil fertility, and that perfecting a crop rotation plan, considering all the factors, is of less import.

Planting and Cultivation

We amended our soil with mushroom manure when we were first establishing the garden. We would recommend repeating this once yearly addition of mushroom manure (to be applied in the spring, before planting has begun). We would occasionally add compost to the soil, and we would recommend the continual addition of compost to improve soil structure and nutrients [3]. When the garden was first established at the new site, we also had the field rototilled twice, but all subsequent soil cultivation was done by hand, using shovels and forks. We would recommend hand cultivation whenever possible, but mechanical rototilling may be necessary at the beginning of the season, depending on the compaction of the soil.

Most of our seeds were purchased from West Coast Seeds. Next year we would recommend contacting West Coast Seeds in advance and asking for donations. However, we were able to get some seeds donated by a charity organization called First Steps.

Most plants were started at the UBC Greenhouse, using potting soil and equipment rented or purchased from the greenhouse. Seed depth and spacing were based on seed packet instructions. Greenhouse employees were responsible for watering and pest management, while we were responsible for moving trays from the “mist chamber” to the regular benches, and then from inside the greenhouse to the field when they reached appropriate maturity (time to maturity varied between crops and cultivars; we mostly based our decisions on visual inspection).

Young seedlings were moved to the new site, and transplanted into the ground. Spacing was based on seed packet instructions or using literary references. Some plants (those grown for their roots, or for quick-maturing leafy greens) were “direct seeded”: seeds were planted directly into the ground. When recommended, we mixed a small amount of fertilizer when transplanting seedlings or planting seeds. Fertilizer was mixed accordingly[2]:

- 4 parts alfalfa

- ½ part bone meal

- ½ part lime

- ½ kelp meal

We irrigated using a combination of drip irrigation, and hand watering with a hose and nozzle. The drip irrigation consisted of plastic tubing that was fixed in place, and attached to the main water source. We would periodically turn on the irrigation, and leave it for an hour or two. This method of irrigation was used for crops that grow slowly, and require more management. We used drip irrigation for tomatoes, winter squash, pumpkins, zucchinis and cucumbers. For the remainder of crops, we used a hose and nozzle, and watered by hand.

Certain crops also required specific management, which is discussed further in the appendix.

Depending on the product, harvesting was completed by hand or with secateurs. Roots (such as carrots and beets) could be pulled by hand, and larger leafy vegetables (kale and chard) could be snapped off easily by hand. Vegetables with thicker stalks (broccoli) had to be cut using secateurs.

Nutrient Recapturing

We moved the three-bin compost system that was built for the previous garden to the new site. We used this system primarily for organic waste that would break down quickly. We had a separate compost pile on the site (that was managed by Seane Trehearne) that we used for particularly noxious weeds, woody debris and if we needed to divert some of the volume from our three-bin system. In general, the three-bin system worked well. We used one bin to receive waste, and once it was full we would “turn” it into the next bin (making sure that newest waste was on the bottom). Once the material in this bin seemed to have broken down sufficiently, we would sort through it, moving the most decomposed matter into the third bin, where it would stay until we needed to use it.

This system probably could have been turned more frequently. It would be beneficial to improve the efficiency of this system so that it could process even more of our organic waste. We did not check the C/N ratio of the finished product, and we could have added more carbon material to the bins. The carbon material that we did add mostly consisted of cardboard and dried maple leaves from surrounding trees.

Fall Management

From early October to mid November, our work in the Garden consisted of dismantling irrigation systems, hoop houses, tomato staking and pole bean trellising, composting old crops, planting garlic and cover crops, and putting leaf mulch on beds. We continued to sell produce to Agora, and we continued weekly donations of produce until mid-October. We also continued the Market Stand until the first week of November.

Processing

We found that processing our vegetables was a good way to preserve them, particularly at the height of summer when we didn’t have a market outlet for all of our food. We pickled radishes and cucumbers, and made kimchi with pac choy. We are unsure about the legality of selling goods that are not processed in a Foodsafe kitchen. Gaining access to such a kitchen (or any kitchen at all) might be difficult. In the future we would recommend making an agreement with Agora about our access to their kitchen.

Storage

One of the biggest barriers to long-term storage was a lack of refrigerated space. We had access to the fridge in the LFSUS “kitchen” space, but it was shared with the Wednesday Night Dinner committee, who used it weekly. The majority of produce was stored in large plastic bins, with lids. Leafy products (kale, chard) were stored in a “water bath;” in a plastic bin with enough water in the bottom to reach the stems.

Whenever possible, we tried to reduce the time that produce was stored in the fridge (by harvesting immediately before delivery). However, as the fridge is a communal space, shared with the LFS Undergraduate Society and the Wednesday Night Dinner group, this was not always possible. This resulted in the quality of some produce being reduced. We would recommend having a separate fridge for the Orchard Garden.

Distribution

Most of our deliveries were made on foot, using a wheel barrow, though we used vehicles when we had access to them. Typically we were traveling only to the MacMillan building, either delivering to Agora or setting up our market stand. If the Garden is to engage with a broader UBC community in the future (e.g. Sprouts, cafes such as The Perch in the new Student Union Building), we recommend the team accesses a bike and invests in a bike trailer.

CSA

In the past (from 2011-2013), the OG has had a CSA starting in mid-summer and ending in fall. However as we spent much of the spring establishing the new garden, we were apprehensive about committing to producing enough food for consistent weekly boxes. The space was also much smaller than the last location, and we were unfamiliar with the productivity of the site. Unfortunately, this often meant that we had an excess of produce. In our experience with the CSA in 2013, it was a great outlet for the produce, and was supported by community and faculty. From the perspective of the production team, running a CSA is highly relevant skill for any future work in small scale, organic agriculture. We also found that the model of a CSA works well with the style of production at the Orchard Garden: typically the Garden produces a high diversity of crops but relatively low volume of each. For the next season, we would absolutely recommend re-instating the CSA, for anywhere between 10 and 20 shares (depending on size/pricing of the shares).

Agora

During the fall of 2013 and 2014, we supplied Agora with vegetables, primarily beets, carrots, zucchini, chard, kale, potatoes and garlic. We would receive orders from Agora on Thursdays, and we would confirm that we had the amount required by Friday. We would then harvest on Monday morning, and have the produce delivered by Monday afternoon.

We found the incongruency between Agora’s menu and what was available in the garden frustrating. Frequently, Agora did not want what we were growing, and we were not satisfied with the method of sending them a “Fresh Sheet” explaining what we had, as they often only selected very few items from the list. We felt that there is a disconnection between the garden and Agora, and ideally we wish that their menu could be more flexible and more able to accommodate our produce. Alternately, the Garden could co-ordinate with Agora to produce higher volumes of a select number of crops. As both the Garden and Agora experience a high yearly turnover of team members, it is difficult to maintain a consistent relationship that appropriately reflects the desires of Agora and the Garden.

In the summer of 2014, we mainly communicated with two Work Study students who were in charge of processing (blanching and freezing) for Agora. Again, we felt restricted to the Agora menu, and while we initially got the impression that all the items we were growing would be used, we found that they did not want many of the things we were growing (fresh greens, cabbage, turnips, kohlrabi, beets).

Food Bank

Mid way through the 2014 growing season, we contacted the AMS Food Bank and began donating produce weekly. We feel that this could be a valuable addition to the OG mandate, as the food bank does not usually get fresh produce donations. Although we feel that selling produce is important for modelling an urban production garden/farm, we also acknowledge the ability of the garden to increase food security on campus. Additionally, we were having difficulties finding market outlets for Orchard Garden food, particularly at peak season towards the end of the summer.

Market Stand

Given that we were not running a CSA in the summer/fall of 2014, and Agora’s demand for our produce was very limited, we orchestrated a Market Stand aimed at students and faculty. In addition to bringing in a small source of revenue for the garden, it helped increase the visibility of the garden, and created a stronger connection between the OG, at its new site, the LFS faculty, and the broader UBC community.

Marketing

When we began our positions at the Garden in 2013, we inherited pre-existing working relationships with Agora and Sprouts, as well as the members of a CSA program. Although we created a new connection with the AMS Foodbank and opened a market stand, our marketing promotion of the Garden was fairly limited. We approached the Foodbank about donating, and we promoted our market stand through Facebook posts and posters around the Macmillan and Neville Scarfe buildings. Through our connection with Roots on the Roof (a prospective AMS club student-run garden on the new SUB roof), we have begun communicating with The Perch restaurant (also in the new SUB) about supplying them with produce through the summer and fall.

Similarly, Orchard Garden events were promoted through our Facebook page, blog, and Instagram, as well as via posters, LFS US newsletters, emails sent out to the GRS program, and Education faculty newsletters. In the fall of 2014 we set up a booth at the AMS Sustainability Fair, with interactive activities and information about the Garden.

We would recommend communicating with Agora's marketing representative and encouraging the cafe to highlight OG produce, in signage, newsletters etc. This would encourage awareness of the Garden, and interest in work study jobs, volunteer opportunities or directed studies projects. Likewise it would be interesting to see this done by Sprouts and the AMS Foodbank. As a means of exposure for the Garden, The Perch could be a particularly useful platform, as it will likely have a high volume of UBC students and faculty passing through, many of whom would otherwise have no connection to LFS or on campus agricultural programs.

Our Learning

File:Garden Plan 2015 - East.pdf

Managing the Orchard Garden for the past two years has provided us with the opportunity to put into physical practice our academic study. Designing the new site allowed us to apply our knowledge of agroecological systems, and we learned how to plan and execute a growing season in an urban food production site. The re-establishment of structures in the new site, and the building of a new shed, provided us with an opportunity to learn about simple construction and tool use. Instigating and running a market stand gave us a chance to practice communicating with customers and community members. Managing the Garden’s Facebook, Instagram, and blog helped us build skills in maintaining an organization’s online /social media presence. Some aspects of managing the Garden we found challenging included record keeping of seeding and harvests, appropriate co-worker and volunteer delegation of tasks, and coordinating with Agora and other organizations to find outlets for our food.

While the Education faculty holds workshops, practicums, and events in the Garden, we feel the Garden is underutilized by Land and Food Systems. It has the potential to be an amazing resource for LFS faculty and students. We would love to see the Garden integrated into the syllabus of plant, soils, agro-ecology, and the LFS core series courses. From our perspective, in an ideal situation, LFS faculty would actively seek to integrate the garden into curricula. This has consistently been one of our biggest frustrations. Additionally, we feel that the separation of the Orchard Garden team into ‘Production’ and ‘Programming’ compartments contributes to the dissonance between different types of knowledge. If the Garden is to continue functioning as a collaboration between LFS and Education, we feel that this should be addressed.

References

- ↑ Bee Informed. (2015). Bee Informed Partnership. Retrieved online from: http://beeinformed.org/2013/11/the-basics-of-moving-hives/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Jeavons, J. (2002). How to grow more vegetables. Ecology Action.

- ↑ Brady, N. C., & Weil, R. R. (2010). Elements of the nature and properties of soils. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Photos

External Links

AGSC 450: Expanding the LFS Garden, 2008 A plan to expand the initial small garden at Macmillan Building, including a budget, outlines for a manager position, and methods for integrating the garden into the Land and Food Systems faculty.

AGSC 450: Practicing Urban Agriculture Right Here: Integrating the LFS Garden with the Faculty of Land and Food Systems Community: Management, Resources, and Budget, 2009 A proposal offering recommendations surrounding issues of garden management, including management plans, budgeting, funding and resources. One of three projects concerning the LFS Garden in 2009.

AGSC 450 Group Project: Practicing Urban Agriculture Right Here: Integrating the LFS Garden with the Faculty of Land and Food Systems Community An investigation and establishment of the ties necessary for future educational opportunities and community involvement with the LFS Orchard Garden. The second of three projects concerning the LFS Garden in 2009.

LFS 450: The UBC Food System Project: Summary, 2010 A summary of the 2010 iteration of the University of British Columbia Food System Project, with an overview of central group tasks, findings, and recommendations as well as some central outcomes.

LFS 450: Management Models: AMS SUB Roof-Top Garden for Productivity and Community, 2012 A discussion of various management options for a production oriented rooftop garden on the new Student Union Building, along with recommendations and implementation plans for human resource management.

Farm to Fork Cookbook Recipes using local and seasonal ingredients, and featuring twelve local food outlets or promoters on UBC campus

Social Media Sites

The Orchard Garden Blog - blogspot

The Orchard Garden Blog - landfood blogs

Partners

Appendix A - Production 2014

Block A: salad greens

-varieties: head lettuce (buttercrunch), arugula (perennial/wild), spinach (tyee hybrid), mesclun mix

-notes: greens were hard to grow this summer because of too much heat, lots of bolting problems, nowhere for the greens to go (need to be harvested constantly or they’ll bolt).

-agora only wanted spinach (for freezing)

Block B: alliums

-onions (sweet spanish, walla walla), leeks (bandit), scallions (purple and white)

-notes: this section was much smaller this year because we had no garlic (in the future it will require many more beds), onions got huge, but took a very long time (from may-august)

Block C: root vegetables

-varieties: carrots (danvers, nantes, nantes coreless), beets (touchstone gold, chioggia, bull’s blood, red ace), turnips (purple top white globe, hakuri), chard (bright lights, fordhook giant, ruby red), parsnips (gladiator), rutabaga (swede)

-notes: parsnips and rutabaga did not come up at all. could be because of old seeds for the rutabaga (they were donated), or heavy soil texture, even though we used a fork, and mixed peat moss in the rows (parsnip seeds were freshly bought)

-chard should maybe be in the greens section, unsure about this

-agora loves beets and carrots, does not love turnips

-turnips do not last as long as carrots and beets

- Beets and carrots did significantly better under remay!

-carrot germ was good, but we used a fork and mixed in peat moss (don’t use fertilizer, as it apparently causes forking)

Block D: cucurbits

-varieties: cucumbers (straight 8, english long, pickling), zucchini (black beauty), pumpkin (sugar pie), summer squash (crookneck), winter squash (acorn, butternut, hubbard), watermelon (sugar baby)

-notes: too many cucumbers!, it’s hard to find places for them to go in the summer (agora doesn’t want them) and the plants are really productive (we pickled some)

-watermelons were successful! we didn’t even use cover!

-three sisters bed: planted beans and squash when corn was 1-2 feet tall, but beans seemed to overtake corn quickly (corn still produced)

-squash take seriously a lot of space

-cukes could be trellised for easier harvesting and to save space

Block E: potatoes

-varieties: warba, yukon gold, a purple variety saved from the year before

-notes: hard to find a method for mounding, needed more soil and a way to keep it from falling. we tried using wooden frames, but plants were already too big

Block F: fabaceae

-shelling peas, sugar snap (little marvel), pole beans (purple peacock, blue lake), bush (eureka, festina)

-peas did very poorly, very slow, many died, were not productive (maybe because it was too hot, or because peas like well drained sandy loam soil, and we have clay)

Block G: solanaceae

-varieties: basil (rosy, genovese, holy (tulsi), lemon, thai (cinnamon)), okra, tomatoes (stupice, beefsteak), cherry tomatoes (sun gold, black cherry)

-notes: we did one row under cover, two not covered

-hoop houses were always at risk of being blown over, as wind can get very strong and the site is quite exposed

-irrigation is super important, as hand watering was really difficult (no overhead watering allowed, water penetration was extremely low)

-staking needs to happen early on, as well as pruning (both need to be done regularly) especially for varieties with large fruit

-more research could be done about how aggressive to prune

-starts need to be put in extremely early (early may) or fruit may not ripen

Block H: brassicaceae

-varieties: kale (improved siberian, vates blue curled, lacinato, red russian), broccoli (natalino, everest, gypsy), cabbage (copenhagen, sui choi), kohlrabi (kongo), brussels sprouts (gustus),

-notes: kale did great, but one variety (maybe improved siberian?) got a white mildew

-broccoli did excellent!

-needs to be harvested early (agora did not want it)

-all brassicas should be covered with remay (it dramatically decreased pest problems)