The Medicalization of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Medicalization, a concept introduced by sociologists, helps illustrate how the application of medical knowledge on human behavior can transform normal processes into perceived abnormalities.[1] This social process has deep-rooted association with dominant Western medicine, as well as the pharmaceutical industry, and is influenced by aspects such as the medical model, societal beliefs, economic conditions, scientific hypotheses or evidence, and consumerism.[2]

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a psychological disorder occurring “following an extreme traumatic event, in which a person re-experiences the event, avoids reminders of the trauma, and exhibits persistent increased arousal.”[3] The medicalization of PTSD refers to the process where a human condition, not explicitly medical or biological, has evolved to become regarded as disorderly, and therefore treated as a medical problem. The development of PTSD as a medical disorder began in the mid 1970’s at the end of the Vietnam War, and has since progressed to be considered a serious mental illness.[4]

History

At the end of the Vietnam War during the mid 1970’s, several American veterans were having difficulties adjusting back into their daily life upon returning home due to the traumatic events experienced at war.[3] Psychological assistance was sought by almost a quarter of the veterans, which ultimately led to their condition being termed as Post-Vietnam Syndrome by the medical community.[5]

The idea of adding such a syndrome to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was at first doubted by American Psychiatric Association (APA).[3] The APA’s argument was that the disorder had a clearly identifiable cause, which wasn’t in alignment with the DSM ideology that focused on mental disorders with no explicit causal factor. However, due to the sociopolitical pressure in wake of the Vietnam War, in 1980, PTSD was added into the 3rd edition of the DSM. At the time, PTSD was understood to be a “normal response to an abnormal stressor;” the abnormal stressor referring to war trauma, which was considered by the APA, “outside the range of usual human experience.” The emphasis was placed on the traumatic experience itself rather than the victim.

After its inclusion into the DSM, there was a significant increase in the diagnosis of PTSD.[4] As the DSM evolved, the criteria for its diagnosis changed several times to be more inclusive of other traumatic experiences. In the current version of the DSM, titled the DSM-5, the focus has shifted from the stressor, to the psychological effects experienced by the victim.[3] PTSD is currently considered a “pathological response to an extreme form of stress[;]” stressors now expanding from combat to include sexual assault, confinement in a concentration camp, and experience of a natural disaster.[5]

Diagnostic Criteria

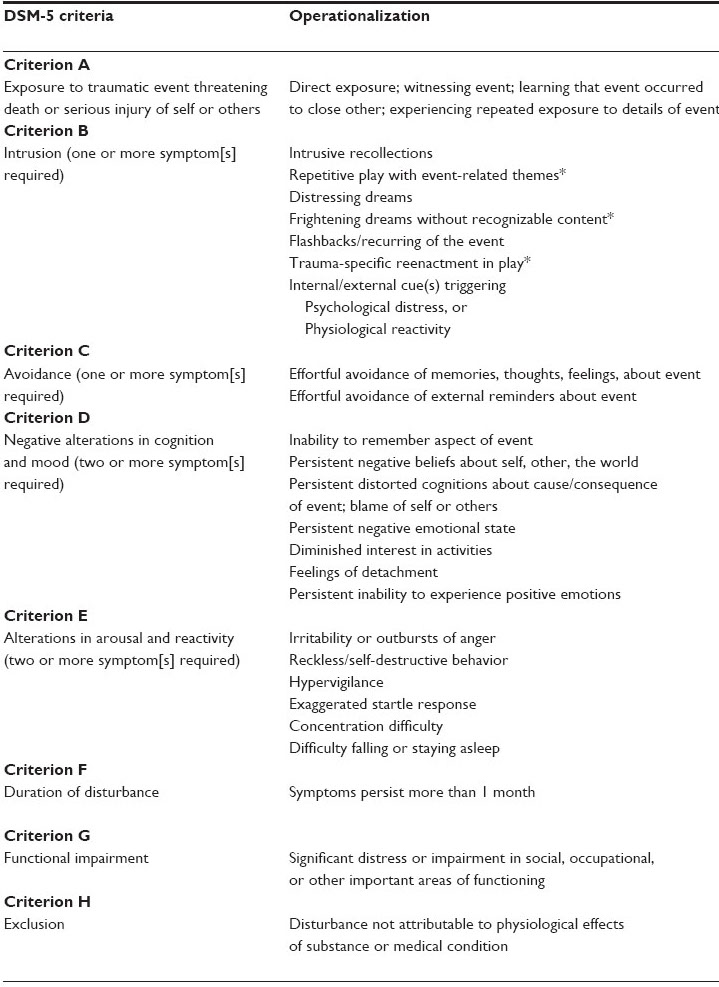

PTSD is classified in the DSM-5 under, trauma – and stressor – related disorders. There are four main groups in which the clinical symptoms of the disorder are categorized into: (1) intrusion, (2) avoidance, (3) negative cognitions and mood, (4) arousal and reactivity. In order to receive the diagnosis of PTSD, the individual who has suffered a traumatic event must meet all the criteria listed within the below image. As a result of the most recent criteria, there are now exactly 636,120 ways one can develop PTSD.[6]

Risk Factors

Diathesis Stress Model

Several people experience traumatic events, however not everyone goes on to develop PTSD. Based on the diathesis stress model, the development of a mental disorder, including PTSD, is often attributed to ones diathesis – their “predisposition or vulnerability to developing a given disorder.”[3] An individuals’ diathesis is influenced by their unique biological, psychological, and sociocultural makeup.

Psychological

Psychological risk factors for PTSD include having a prior mental illness, such as depression or anxiety, substance use disorders, and having a neurotic or extroverted personality. Also, a family history of mental illness is also a notable risk factor for the development of PTSD. [3]

Biological

The most prominent biological factor is gender. Based on the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R), women are twice as likely as men to develop PTSD after a traumatic experience. [7]

Sociocultural

There are various sociocultural factors that influence the development of PTSD after a traumatic experience. These include being a member of a minority group, having a low IQ level, careers in the military or medical field, and having a negative or weak support system.[3] Residing in a post conflict environment, or an area with a high rate of natural disasters also has implications on the development of the disorder.[8]

Treatment

There is no method of treatment specific to PTSD, however there are strategies used to treat stress related disorders in a more general sense. These strategies tend to derive from Western practices that are behavioral and pharmacological in nature. For example, prolonged exposure, a type of cognitive behavioral therapy, is often used as a treatment for PTSD.[3] Within prolonged exposure, the patient works with a professional to work on controlling his or her behavioral response when asked to recall the stressor. The desired outcome of this method is to reach a point where there is no longer a stress response employed when encountering or remember the stressor.

The symptoms of PTSD often overlap with other psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Medications such as antidepressants are often prescribed to treat depressive symptoms; whereas for symptoms of paranoia, antipsychotic medications are used.

Globalization of PTSD

After the addition of PTSD into the DSM in the 1980’s, the medical community took note that the criteria for the disorder aligned with other models of trauma such as rape trauma syndrome, battered women’s syndrome, and trauma related adversities seen in post-conflict areas.[4] Due to its applicability, PTSD soon evolved from its Western origin to be a disorder internationally recognized. Although seen universally, PTSD is experienced quite differently between cultures.

The Western experience of PTSD is manifested by symptoms of psychological basis, however these symptoms are not entirely universal. As an example, the Salvadorian syndrome called, “calorias,” is commonly seen in female victims of civil war, the main symptom being a burning sensation in the body.[9] Afghani victims of war often experience a mental state called, “fishar-e-bala,” described as an internal pressure in the body. In contrast to these bodily experiences, survivors of Sri Lanka’s 2004 tsunami are impacted by their traumatic experience in a different way. Their post-trauma adversities are neither psychological nor physical, but rather focused on the disturbance of ones social role within their group as a result of the natural disaster.[4]

Critiques of PTSD

Almost all individuals will encounter a traumatic event within their lifetime and the following stress experienced is a natural response to the trauma. This has led many to believe that the medicalization of PTSD is the medicalization of natural human behavior.[10]

Furthermore, sociologists believe PTSD has been constructed based on the Western experience.[4] With such cross-cultural variation in post-trauma symptoms, the current criterion may fail to capture symptoms experienced by individuals of non-Western societies.This has implications on diagnosis and recieving proper medical assistance.

References

- ↑ White, Kevin. An introduction to the sociology of health and illness. 1st ed. N.p.: Sage Publications, 2002. Web. https://books.google.ca/books/about/An_Introduction_to_the_Sociology_of_Heal.html?id=5bHxQBNWGHMC&redir_esc=y

- ↑ Vilhelmsson, Andreas, et al. "Mental Ill Health, Public Health and Medicalization." Public Health Ethics, vol. 4, no. 3, 2011, pp. 207-217 https://academic-oup-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/phe/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/phe/phr030

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Butcher, James Neal, Jill M. Hooley, and Susan Mineka. Abnormal Psychology. 16th ed. New Jearsy : Pearson, 2014. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Moghimi, Yavar. "Anthropological Discourses on the Globalization of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Post-Conflict Societies." Journal of Psychiatric Practice, vol. 18, no. 1, 2012, pp. 29. http://gw2jh3xr2c.search.serialssolutions.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Anthropological+Discourses+on+the+Globalization+of+Posttraumatic+Stress+Disorder+%28PTSD%29+in+Post-Conflict+Societies&rft.jtitle=JOURNAL+OF+PSYCHIATRIC+PRACTICE&rft.au=Moghimi%2C+Y&rft.date=2012-01-01&rft.pub=LIPPINCOTT+WILLIAMS+%26+WILKINS&rft.issn=1527-4160&rft.eissn=1538-1145&rft.volume=18&rft.issue=1&rft.spage=29&rft.epage=37&rft_id=info:doi/10.1097%2F01.pra.0000410985.53970.3b&rft.externalDBID=n%2Fa&rft.externalDocID=000299668500005¶mdict=en-US

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 DiMauro, Jennifer, et al. "A Historical Review of Trauma-Related Diagnoses to Reconsider the Heterogeneity of PTSD." Journal of Anxiety Disorders, vol. 28, no. 8, 2014, pp. 774-786. http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S0887618514001261?_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_origin=gateway&_docanchor=&md5=b8429449ccfc9c30159a5f9aeaa92ffb&ccp=y

- ↑ Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). 636,120 ways to have posttraumatic stress disorder. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 651-662. http://journals.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/full/10.1177/1745691613504115#articleShareContainer

- ↑ Kessler, Ronald C., et al. "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey." Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 52, no. 12, 1995, pp. 1048-1060. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7492257

- ↑ Atwoli, Lukoye, et al. "Epidemiology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Prevalence, Correlates and Consequences." Current Opinion in Psychiatry, vol. 28, no. 4, 2015, pp. 307-311. http://ovidsp.ovid.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&AN=00001504-201507000-00008&LSLINK=80&D=ovft

- ↑ Watters, Ethan. "Suffering Differently." The New York Times. N.p., 11 Aug. 2007. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/12/magazine/12wwln-idealab-t.html>.

- ↑ Stein, Dan J., et al. "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Medicine and Politics." The Lancet, vol. 369, no. 9556, 2007, pp. 139-144. http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S0140673607600750