Social Stratification, Intersectionality, and the Vancouver Housing Market

Social stratification concerns the social and economic interactions that contribute to patterns of growing inequality, thus having a lasting impact on the livelihoods and success of those who experience it[1]. In a time where social status has become associated with rent-paying ability, we can consider housing to be a good indicator, and in fact a contributing factor of class and social divides. A lack of affordable housing has tangible implications on many of the pressures giving rise to social inequalities in todays society. These include class divides, homelessness, crime rates, and financial physical wellbeing. Each of these onset implications often exhibit the propensity to interact with one another, introducing a strong element of intersectionality which threatens to exacerbate the issue. The Vancouver housing market is an exceptional case, in which a lack of affordable housing can be seen as a prominent driver of intersectionality and socio-economic inequalities in the urban environment; primarily concerning gentrification, class separation, and other forms of social stratification.

Emergence of Class Divides

Class divides are a social construct, ultimately determined by income levels. Class can be perceived differently by everyone, as can the burden of class inequalities; however most commonly it is lower-income individuals, or the ‘working-class’ that become increasingly marginalized as a result of class divides and social stratification. A common way in which class inequalities can be accentuated is through the process of gentrification, the redeveloping of neighbourhoods to conform to middle- or upper-class expectations. This very often results in housing prices being driven up, thereby marginalizing and pushing out lower class communities due to the increased cost of living.

The Rise of Housing Costs and Gentrification

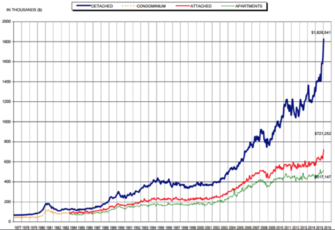

Figure 1 illustrates the steady rise in average housing prices in Greater Vancouver from 1977-2016, from this we can infer that a significant percentage of residences have been made unaffordable to Vancouver’s working-class individuals, leading to extensive class stratification. In part, Vancouver’s neoliberal public policies have been largely responsible for facilitating increases in housing costs, and subsequent gentrification during the last 50 years, as 1960s policies were replaced with urban renewal programs giving loans and grants in favour of housing renovation[2]. The underlying philosophy behind the implementation of these policies, and the resulting state is explained by Blomley[3]:

Programs of renewal often seek to encourage home ownership, given its supposed effects on economic self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and community pride. Gentrification, on this account, is to be encouraged, because it will mean the replacement of a marginal anticommunity (nonproperty owning, transitory, and problematized) by an active, responsible, and improving population of homeowners. (Blomley, 2004, p.89)

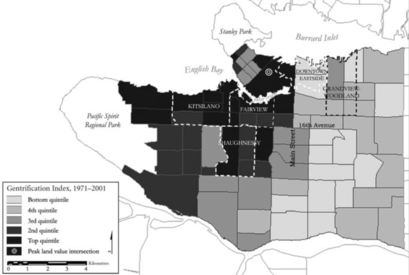

In particular, Blomley was referring to Vancouver’s Downtown East Side (DTES), an area characterized by significant rent-gap, poverty, and crime when compared with the inner city districts only 1km away[2]. These circumstances would normally give way to rapid gentrification, but in the case of the DTES, gentrification has historically been been somewhat limited due to the poor public perception of the area, and local backlash against further attempts to marginalize the community in the name of urban renewal[2]. Figure 2 illustrates the extent of gentrification in Vancouver from 1970-2001, note that the DTES historically exhibits low levels of gentrification. However, despite the initial resistance, this is no longer the case. As average housing prices in Vancouver continue to rise, as per figure 1, communities with significant rent disparity are becoming targets for gentrification. This is explained by Neil Smith’s[4] ‘rent-gap thesis’, which states that where potential rent far exceeds the actual rents, gentrification is likely to ensue. The current state of the DTES is one of rapid gentrification and displacement of working-class and poor people. This trend is likely to continue given current housing redevelopment plans set by the City of Vancouver[5], which aim to incorporate mixed-income housing in the DTES. This kind of ‘social mix discourse’ is problematic and has been shown to result in ‘uneasy cohabitation’ and poor social cohesion, aggravating pre-existing social inequalities, and causing eventual gentrification and class stratification[6].

Accompanying Impacts

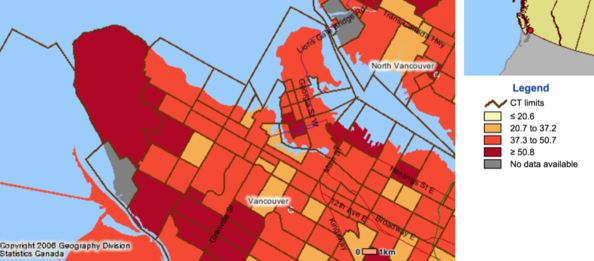

Housing stability can also be closely linked to a wide range of other significant factors and social stigmas that contribute to social divides and inequalities, such as illicit drug use, crime, and medical conditions like HIV. One study on persons who inject drugs in the DTES yielded a strong correlation between unstable housing and daily heroin use, incarceration, sex work, and HIV prevalence[7]. As such, supportive housing programs are essential in order to resolve the current issues that the DTES faces, rather than further housing instability among poorer populations, due to rising prices and gentrification. As figure 2 shows, gentrification has historically been widespread across Vancouver, most notably in the district of Shaughnessy, Fairview, Downtown, West Point Grey, and Kitsilano. The availability of desirable amenities in these areas can be seen as a driver for the increased rates of gentrification. Ley & Dobson[2] show that rates of gentrification increased as distance from amenities decreased; these amenities include waterfront, green spaces, and access to downtown. The reasons for this stem from post-industrial revolution and neoliberal ideologies, whereby land use was dictated by what could justify the highest rents, and economic capital[8]. As such, neighbourhoods of the old inner-core became gentrified, replaced by large, single-family homes which enable owners to charge high rents[9]. Not only did this create class divides by making the area unaffordable to the working-class and lower-income families, it creates challenges for the current population. As figure 3 shows, in 2006 a significant portion of the residents of Kitsilano, Fairview, West Point Grey, and Downtown pay >30% of their personal spending on rent. It is also worth noting that over half of residents of the DTES devote >30% of the personal spending towards paying rent, reaffirming that gentrification through housing prices is occurring in this traditionally low-income neighbourhood. High housing costs such as these accentuate the wealth disparity between renters and owners, thereby furthering existing class stratification.

Immigrant Populations and Racial Segregation

The Main street divide represents a clear separation of both class and race in Vancouver, as the historical division “between a blue-collar, non-Anglo Eastside and a white-collar, middle- and upper middle-class, Anglo-Canadian Westside”[2]. Traditionally immigrant populations would choose to settle in ethnic enclaves, which are more culturally familiar, which therefore gives rise to dense regions of cultural homogeny[10]. As a result of a high supply of immigrants into the workforce, particularly in low-level jobs, wages can be driven downward; this creates an immigrant population that will tend to settle in areas of low-income housing, creating an ethnic enclave comprised of low-income populations in low level housing[11][12]. Vancouver’s Chinatown is a prime example of this. When ethnic enclaves become at risk of gentrification, the result can be racial segregation and further social inequalities as the populations of low-income housing are driven out. Vancouver is at high risk of this kind of racialization in the housing market due to the comparatively high number of visible minorities, with over 40% of the population comprised of visible minorities[13]. This racial aspect introduces yet another dimension of intersectionality to the issue; victims of poverty may find themselves at the meeting point of financial difficulties and potential racial prejudice that arises when urban environments become segregated in this way.

Vancouver's Challenge

Vancouver finds itself in a unique situation in which communities, particularly this of a lower-income, are more susceptible to social stratification, gentrification, and class divides than other cities. And subsequently, this can bring about a plethora of different social impacts, including poor health and mental well-being, as well as financial and racial prejudice. Intersectionality plays a huge part in exacerbating the issue, and - just like Vancouver's troubled housing market - it can be considered a main driver for inequality and prejudice in the urban environment.

Vancouver’s highly competitive housing market is characterized by ever rising costs, and the expansion high demand, middle- and upper-class housing into areas traditionally comprised of lower-income housing options. Thereby causing a wide range of communities to be left vulnerable to gentrification, class stratification, and socio-economic challenges and inequalities.

References

- ↑ Bottero, W (2004). "Stratification: social division and inequality". Routledge.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Ley, D., & Dobson, C. (2008). Are there limits to gentrification? The contexts of impeded gentrification in Vancouver. Urban Studies, 45(12), 2471-2498. Retrieved from https://bral.brussels/sites/default/files/bijlagen/Ley_Dobson_2008_are%20there%20limits%20to%20gentrification.pdf

- ↑ Blomley, N. K. (2004). Unsettling the city: urban land and the politics of property. Psychology Press.

- ↑ Smith, N. (1987). Gentrification and the rent gap. Annals of the Association of American geographers, 77(3), 462-465.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. (2014). Downtown Eastside Plan. City of Vancouver, Vancouver, Canada. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-plan.pdf

- ↑ Rose, D. (2004). Discourses and experiences of social mix in gentrifying neighbourhoods: a Montreal case study. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 13(2), 278.

- ↑ Zivanovic, R., Milloy, M. J., Hayashi, K., Dong, H., Sutherland, C., Kerr, T., & Wood, E. (2015). Impact of unstable housing on all-cause mortality among persons who inject drugs. BMC public health, 15(1), 1. Retrieved from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-015-1479-x

- ↑ Ponder, S. (2016a). Industrial Cities [Lecture notes]. Lecture on September 22, 2016. Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

- ↑ Quastel, N. (2009). Political ecologies of gentrification. Urban Geography, 30(7), 694-725.

- ↑ Choo, K. S. (2007). Gangs and immigrant youth. LFB Scholarly Publishing.

- ↑ Moos, M., & Skaburskis, A. (2010). The globalization of urban housing markets: Immigration and changing housing demand in Vancouver. Urban Geography, 31(6), 724-749.

- ↑ Walks, R., & Bourne, L. S. (2006). Ghettos in Canada's cities? Racial segregation, ethnic enclaves and poverty concentration in Canadian urban areas. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 50(3), 273-297. Retrieved from http://neighbourhoodchange.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Walks-Bourne-2006-Ghettos-in-Canadas-Cities.pdf

- ↑ Statistics Canada. (2006). Visible minority population, by census metropolitan areas (2006 Census) [Tabular data]. Ottawa. Version updated November 2009. Ottawa. Retrieved on Dec 5, 2016 from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo53g-eng.htm