Representational Intersectionality

Intersectionality Defined

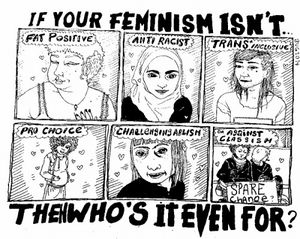

Intersectionality is a term that defines how different forms of prejudice such as racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and xenophobia are interlocked and must be examined together to begin to understand why people who are apart of multiple minorities face the greatest oppression [1]. This term was coined by Kimberlè Crenshaw in the context of feminist theory [1]. This term arose when Crenshaw noticed that the first and second-wave mainstream feminist movements had little to no representation of African American women [1]. While feminism has been considered to have grown in terms of intersectionality since the third-wave [2], the objectification and social injustice of women of colour is still subliminally enforced in various forms of media. In light of this, Crenshaw expanded on the concept of intersectionality by defining and raising awareness of representational intersectionality.

Representational Intersectionality

Representational intersectionality explores how gender, race, and sexuality are linked and enforce oppressive stereotypes about women of colour in various forms of media, especially film and television. While middle-class white women are often represented in various roles and portrayed as liberated, living in a post-patriarchal society - women of colour are often not. Women of colour are represented in more narrow, stereotypical roles, thus holding them in the same subordinate, oppressive state that many unaffected people believe our society has overcome. They are hyper-sexualized, portrayed as sassy, and associated with crime - to name a few [3]. Crenshaw claims Latina women are portrayed as a "loud, unscrupulous, racialized other"; African-American women "wild and animal-like"; and Asian-American women as passive [4]. By appropriating the "wild-woman pornographic myth of black female sexuality"[3], as well as other narrow stereotypes of women of colour for means of entertainment and economic growth, most problematically this may influence violence against women of colour [4]. This was an issue in the past, as feminists such as bell hooks and Kimberlè Crenshaw have outlined, and critical analyses of TV shows and films reveal that it is still an issue to this day.

Statistics

- "An estimated 29.1% of African American females are victimized by intimate partner violence in their lifetime (rape, physical assault or stalking)" [5].

- "African American females experience intimate partner violence at a rate 35% higher than that of white females, and about 2.5 times the rate of women of other races" [5].

- "Approximately 40% of Black women report coercive contact of a sexual nature by age 18" [6].

- "48% of Latinas in one study reported that their partner’s violence against them had increased since they immigrated to the US" [6].

- "A survey of immigrant Korean women found that 60% had been battered by their husbands" [6].

- "In a content analysis of 31 pornographic websites, of the sites depicting the rape or torture of women, nearly half used depictions of Asian women as the rape victim" [6].

These statistics are placed to support the notion of heightened violence against women of colour by Kimberlè Crenshaw. While stereotypes of women of colour presented in media do not directly cause violence against such minority groups, they marginalize women of colour and enforce the patriarchal subordinate role of women; a significant aspect in the prevalence of violence against women, which white-middle class women have made more progress to move away from, and clearly women of colour are having more of a struggle to do so.

In Television

Glee

The TV show Glee is very obvious in its tokenism, featuring a primarily white cast with minimal minority female characters; one Hispanic girl, one Asian-American girl, and one African-American girl. The one Hispanic female character; Santana Lopez, has very few lines in Season one up until Episode 11 when she was given a few lines about "sexting" [7]. Aside from her minimal lines, Santana's character seems to revolve around her sexual aggressiveness. She has several romantic relationships, takes another character's virginity, and later realizes she is a lesbian. Tina Cohen-Chang, the one Asian-American character, is initially portrayed as so shy that she fakes a stutter to avoid talking to people [7], but later evolves into a confident, out-spoken girl after some time in the glee club. Regardless, Glee was clearly trying to portray the shy, passive Asian woman stereotype. Mercedes, the single African-American character, is loud, sassy, and has a great sense of self-worth. While Glee deters from the stereotypical hyper-sexual African American role, they still play in to the loud, sassy stereotype.

Orange is the New Black

While this Netflix original series has been recognized for deconstructing many marginalized groups such as African-Americans, Latinos, and members of the LGBT community, they failed to challenge the stereotypes of Asian-American women in their portrayal of their two token-Asian characters [8]. Chang, the only Asian character in the first season of the show, is very quiet - she rarely speaks, and when she does it is in a thick accent. Soso, a half Japanese half Scottish character, is fetishized as two lesbian inmates, Nicky and Big Boo, compete to see who will be able to seduce her first. Big Boo objectifies Soso and calls her "the hot one with the Asian persuasion" [8].

In Film

Pitch Perfect

Pitch Perfect, yet another production dominated by whiteness, features only a few minority characters in very stereotypical roles. Lilly, an Asian character, is portrayed as strange, and very quiet [9]. Cynthia-Rose, an African-American character, is loud and out-spoken, and rarely put in the spotlight throughout the movie unless to make humour of her sexual orientation [9].

References

1. [1] Miyazato, C., & Miyazato, C. (2016, November 06). Intersectional Feminism 101 – Athena Talks – Medium. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://medium.com/athena-talks/intersectional-feminism-101-3a39f372bcba

2. [3] Hooks, B. (1992). Black looks: Race and representation. Boston: South End Press. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://aboutabicycle.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/bell-hooks-black-looks-race-and-representation.pdf

3. [4] Matsuda, M. J. (1993). Words that wound: Critical race theory, assaultive speech, and the First Amendment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780429502941/chapters/10.4324/9780429502941-5

4. [2] OH Blog and News. (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2019, from http://www.ohiohumanities.org/betty-friedan-the-three-waves-of-feminism/

5. [5] http://www.doj.state.or.us/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/women_of_color_network_facts_domestic_violence_2006.pdf

6. [6] https://www.pcc.edu/illumination/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2018/05/domestic-violence-communities-color.pdf

7. [7] Landweber, M. (2018, February 25). Is 'Glee' a Little Bit Racist? Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://www.popmatters.com/117255-is-glee-a-little-bit-racist-2496137011.html

8. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santana_Lopez

9. I'm a match to Mercedes Jones from Glee. (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://www.charactour.com/hub/characters/view/Mercedes-Jones.Glee

10. [9] Dixon, C. L. (2018, February 02). Things about Pitch Perfect you only notice as an adult. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://www.thelist.com/101609/things-pitch-perfect-notice-adult/

11. [8] Kim, C. (n.d.). The Blindspot: Asian Misrepresentation In Orange Is The New Black. Retrieved March 1, 2019, from https://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/elements/article/view/9380

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Intersectionality".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Three Waves of Feminism".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 hooks, bell. "Black Looks: Race and Representation" (PDF).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Crenshaw, Kimberle. [file:///Users/jennifer/Downloads/10.4324_9780429502941-5.pdf "Beyond Racism and Misogyny"] Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Women of Color Network Facts - Domestic Violence" (PDF).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Domestic Violence Communities Color" (PDF).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Is Glee A Little Bit Racist".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Asian Misrepresentation in Orange is The New Black".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Things About Pitch Perfect You Only Notice As An Adult".