Orientalism and Gender

Introduction

Orientalism within the historical, philosophical, and political discourses is the longstanding production and maintenance of a set of Western produced oppositional binaries and imposed values relating to the culture and ethnicity of the Middle East and Western Asia. To many, Orientalism and Orientalist concepts, such as mission civilisatrice and ‘The White Man’s Burden’, provided the rationalization of European intervention and colonization of the Middle East and Western Asia. [1]. Through a network of invented binaries, Orientalism seeks to order the world in a hierarchy of the familiar and ‘The Other’ and through this system, power can be dispensed. Western perspectives of Eastern bodies features prominently in Orientalism; gender is both interpreted and imposed through binaries and this process demonstrates how Western discursive power is projected onto the Other.

Theoretical Background

Edward Said (1935-2003), a prominent philosopher of the 20th century, in 1978, coined this term and it has been used to describe the Eurocentric or Western perspective of the East or Orient. To Said, Western depictions of the Orient have often positioned the Middle East as an “exotic locale” with romantic themes of “sensuality” and “idyllic pleasure” while simultaneously positing a perception of the Orient as antithetical to the West, a space of moral depravity, barbarity and backwardness [2]. This set of invented portrayals and values provided a point of reference and fixed characteristics for Westerners in their relationships with the Middle East and have consistently been reproduced in art, literature, media, and other mediums [3].

Other scholars, such as Ali Behdad, have characterized Orientalism as “a network of aesthetic, economic, and political relationships that cross national and historical boundaries” [4]. Orientalism intersects and informs various disciplines and methodologies to create overarching binary oppositions between Eastern and Western cultural and ethnic identities. Therefore, theoretical schools, such as Postcolonialism and Feminism, have attempted to challenge this metanarrative and the oppositional binaries that underpin it.

Oppositional Binaries

Orientalism, as a process within both the academic and public discourses, is rooted in oppositional binaries, often called binary opposition. Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) is credited with this concept and, simply, put, “binary opposition is the system by which, in language and thought, two theoretical opposites are strictly defined and set off against one another but simultaneously arranged, somewhat paradoxically, in pairs.” [5] [6] Binaries can be both simple, such as raw/uncooked, and complex, like realism/liberalism and are both socially constructed and arbitrary.

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) added an important caveat to binary oppositions and how they relate to Orientalism. Derrida noted “the tendency of Western thinkers to privilege one term in a binary opposition over the other term, thus creating a hierarchy that organizes thought….[which] appears to be a stable and natural [system].” [7] In terms of Orientalism, binaries are constructed in such a way so that there are disparate ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ terms within a system or network where the Middle East and Western Asia are subordinate to the West. Orientalism is, therefore, exists to impose a hierarchy of power between the above cultures.

Binaries within Orientalism

It is important to recognize the invented and subjective Orientalist binaries so that they can be recognized, questioned and challenged. These binaries are often represented in art, literature, media, and other mediums, but can also be found the portrayal of historical or political events. Importantly, the ‘Western’ component of the binary, such as modernity or civilization, is often implicit, while the Middle Eastern and Western Asian element is stated or exaggerated.

The binaries below provide a snapshot of the network of terms and concepts that form Orientalism and how these sets create active juxtapositions for the Westerner.

- East/west

- Good/evil [8]

- Black/white

- Modernity/tradition [9]

- Exotic/ordinary

- Reason/dogma [10]

- Cruel/gentle

- Progressive/backward [11]

- Democracy/despotism [12]

- Civilization/ medievalism [13]

- Sensual/chaste

- Rational/irrational [14]

- Liberty/servitude

- Effete/masculine

- Degenerate/moral

- Civilized/barbaric [15]

This sample of binaries demonstrates the complexity and arbitrariness of the sets that reside within Orientalist thought. Note that some of these binaries are gendered, as this is a significant component of Orientalism.

Painting Gender into the Orient

Gender features heavily in Orientalism and the network of binaries that form this concept. The Eastern Man and Woman are portrayed through multiple lenses within this paradigm and certain values, such as the exotic and the effeminate, are affixed to these representations to inform the Western reader. While many of these labels are benign, threat and mystery are also present in gendered characterizations of the Middle East and Western Asia.

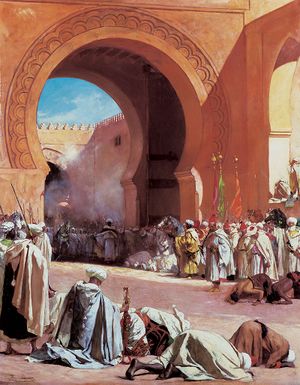

In the 1800s, artwork played an important role in gendering Middle Eastern men and women. An entire genre or school of art – Orientalism – was established in this period and still remains popular in the West. Europe yielded celebrated painters, such as Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and Frederick Lewis (1804-1876) among others, who created evocative and picturesque works that attempted to “capture the exotic otherness and colours [of the Orient]… to reproduce dress, customs and architecture as faithfully as they could and…to portray the seamier side of life – the poor, the lame, the blind, [and] the beggars.” [16] These fantasies consisted of binaries, which included the “erotic and the exotic… the savage and the sensual.” [17]

Delacroix’s La Mort de Sardanapale (1827) or The Death of Sardanapalus depicts the death of an Assyrian king and demonstrates how multiple values, such as the erotic and the savage, can be portrayed within one work. While the naked women and the violence confirm the ‘negative’ Middle Eastern component of the binaries, there is an implicit understanding that Western society and values provide the polar opposites of this scene.

Violence is a key concept in the corpus of jaundiced or 'negative' stereotypes that form the Orientalist binary network. In Henri Regnault's Exécution sans jugement sous les rois maures de Grenade (1870) or Summary Execution under the Moorish Kings of Grenada, the Oriental despot calmly cleans his bloodied sword with his extravagant cloak. Brutality and opulence are active concepts in this work and provide the unstated comparison between Eastern arbitrariness versus Western justice.

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant's The Favorite of the Emir (1879) has explicit gendered values attached to the subjects in his work. Both women poses suggest luxury and decadence and, thus, there is a tacit understanding that the Western reader is frugal and virtuous in comparison. But, crucially, this painting demonstrates Westerner's view of Muslims as "lusty and sexually perverse," with women, like the subject, considered "constantly available for the erotic gratification of oversexed Muslim men." [18] Women of the Middle East are a source of curiosity and hold an aura of mystery to the Western viewer. These views are compounded by the plethora of values, tropes, and concepts that form Orientalism's pervasive network.

Scripting the Bodies of the Orient

Gender and Orientalism feature heavily in literature and offers another glimpse into the binaries foisted onto Middle East/ Western Asia by the Western Orientalist discourse. Furthermore, this medium exposes the strong, Orientalist anxieties held by Westerners with regard to white women fraternizing with Arab men. In E.M. Hull's, The Sheik (1919), a young English aristocratic woman is kidnapped and raped by an Arab Sheik in Algeria. This young lady falls in love with her rapist but discovers that he is half English aristocrat and half Spanish, whereupon the two 'go native' and ride off into the desert. [19] This work exposes the paradoxes within Orientalism as the 'savage' Arab rapes the white virgin, but the pure/strained and brutal/gentle binaries are swiftly overturned when the Arab is unveiled to be a Westerner. Moreover, the white woman's innocence is returned when she commits to a Westerner, which implies that the male has greater agency over the female body. Hull's work exemplifies both the negative tropes attached to Arab men, the fear of feminine defilement in the West, and the appropriation of women's agency to rectify the virginal/corrupted binary.

William Shakespeare's Othello (1565) provides a reversal of many of the 'negative' components found in Orientalist binaries. However, this reversal requires the full acquisition of Western tropes and the relinquishing of Eastern identity. Othello, Shakespeare's protagonist, is a Moor who embraces "Christian values and assumptions of Venetian society." [20] Furthermore, Othello defends Venice from the Ottoman or 'The Other' and marries a Venetian to acquire European status. 'Negative' binaries, however, still exist in this work as Othello's father-in-law's anger at his daughter's marriage to a Moor is placated by the knowledge that his "son-in-law is far more fair than black." [21] Othello's war conduct and his marriage to a white woman is upsets the traditional binary set and allows him to enter Venetian society. His marriage is an affirmation of his transformation because, in this case, a white woman is able to facilitate his entry into European society. Thus, the oppositional binaries that dictate the West's relationship with the East demand that Othello augment his behavior and, in doing so, his appropriation of Western traits simply inverts long-standing, static binaries, such as black/white or civilized/barbaric. Furthermore, Othello's marriage changes the traditional gender dynamic to demonstrate that women are able to confer social status as a European.

Like visual media, literature plays an important role in producing and maintaining the oppositional binaries that underpin Orientalism. Furthermore, it provides an insight into how gendered norms and values can be applied to Others, such as Middle Easterners, to produce powerful, 'negative' poles in various binary combinations.

References

- ↑ What is Orientalism?. n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2016. http://arabstereotypes.org/why-stereotypes/what-orientalism

- ↑ Edward W. Said. Orientalism. Vintage Books Ed. Toronto, ON: Random House, 1979. 51

- ↑ Said, 1979. 118, 40, 41-42, 206 pgs.

- ↑ Ali Behdad. "Orientalism Matters." MFS Modern Fiction Studies, 56, No. 4 (2010), 711

- ↑ Peter Childs. Poststructuralism. Routledge: London, UK, 200, 64

- ↑ Greg Smith. "Binary Opposition and Sexual Power in 'Paradise Lost'." The Midwest Quarterly. 37.4 (1996), 383-384

- ↑ Postmodernism. Encyclopedia of Social Theory. Ed. George Ritzer. 2005. Sage Publications Online. Web. 27 Mar. 2016

- ↑ Maryam Khalid. "Gender, orientalism and representations of the 'Other' in the War on Terror." Global Change, Peace & Security, 23, No. 1, (2011), 15

- ↑ Mahmut Mutman, "Under the Sign of Orientalism: The West vs. Islam." Cultural Critique, No 1. (1992-1993) 165

- ↑ Mutman, 1992-1993

- ↑ Khalid, 2011

- ↑ Mutman, 1992-1993

- ↑ Mutman, 1992-1993

- ↑ Khalid, 2011

- ↑ Khalid, 2011

- ↑ Tim Sharp. Orientalism. West Coast Line, 43, No. 4. (2010), 94

- ↑ Sharp, 2010

- ↑ Zachary Lockman. Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004. 69

- ↑ Hsu-Ming Teo, Desert Passions. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2012. 87

- ↑ Debra Johanyak. "'Turning Turk,' Early Modern English Orientalism, and Shakespeare's Othello." The English Renaissance, Orientalism, and the Idea of Asia. Ed. Debra Johanyak and Walter S.H. Lim New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. 77

- ↑ Johanyak, 2010